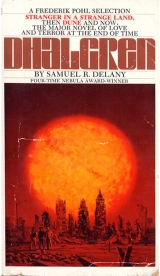

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

“Yeah—well, no. I mean most of it was written in there when I found it. That’s why I wanted to know if it was yours.”

“Oh,” Frank said. “No. It’s not mine.”

Kidd turned from under Jack’s hand. “That’s good. Because when you said you had lost your notebook, you know, I just thought…”

“Yeah,” Frank said. “I see.”

“We’re gonna go out and look for some more girls,” Jack said. “You wanna come along?”

“Jack thinks there’s safety in numbers,” Frank said.

“No. No, that’s not it,” Jack protested. “I just thought he might want to come and help us look for some girls. That’s all. Maybe we can go back to that house?”

“Hey, thanks,” Kidd said. “But I got to hang around here for a while.”

“The Kidd here’s got his own old lady,” Jack said in knowing explanation. “I bet he’s waiting on her.”

“Hey, I’m…sorry it’s not your notebook,” Kidd told Frank.

“Yeah,” Frank said. “So am I.”

“We’ll see you around,” Jack said, while Kidd (smiling, nodding) wondered at Frank’s tone.

Absently rubbing the paper (he could feel the pen’s blind impressions), he watched them leave.

Bumping shoulders with them, Ernest Newboy came into the bar. Newboy paused, pulling his suit jacket hem, looked around, saw Fenster, saw Kidd, and came toward Kidd.

Kidd sat up a little straighter.

“Hello, there. How’ve you been for the past few days?”

The small triumph prompted Kidd’s grin. To hide it he looked back at the book. The poem Frank had left showing had been tentatively titled:

LOUFER

In the margin, he had noted alternates: The Red Wolf, The Fire Wolf, The Iron Wolf. “Eh…fine.” Suddenly, and decisively, he took his pen from the vest’s upper button hole, crossed out LOUFER, and wrote above it: WOLF BRINGER. He looked up at Newboy. “I been real fine; and working a lot too.”

“That’s good.” Newboy picked up the gin and tonic; the bartender left. “Actually I was hoping I’d run into you tonight. It has to do with a conversation I had with Roger.”

“Mr. Calkins?”

“We were out having after-dinner brandy in the October gardens and I was telling him about your poems.” Newboy paused a moment for a reaction but got none. “He was very impressed with what I told him.”

“How could he be impressed? He didn’t read them.”

Newboy doffed his gin. “Perhaps what impressed him was my description, as well as the fact that—how shall I say it? Not that they are about the city here—Bellona. Rather, Bellona provides, in the ones I recall best at any rate, the decor which allow the poems to…take place.” The slightest questioning at the end of Newboy’s sentence asked for corroboration.

More to have him continue than to corroborate, Kidd nodded.

“It furnishes the decor, as well as a certain mood or concern. Or am I being too presumptuous?”

“Huh? No, sure.”

“At any rate, Roger brought up the idea: Why not ask the young man if he would like to have them printed?”

“Huh? No, sure.” Though the punctuation was the same, each word had a completely different length, emphasis, and inflection. “I mean, that would be…” A grin split the tensions binding his face. “But he hasn’t seen them!”

“I pointed that out. He said he was deferring to my enthusiasm.”

“You were that enthusiastic? He just wants to put some of them in his newspaper, maybe?”

“Another suggestion I made. No, he wants to print them up in a book, and distribute them in the city. He wants me to get copies of the poems from you, and a title.”

The sound was all breath expelling. Kidd drew his hand back along the counter. His heart pounded loudly, irregularly, and though he didn’t think he was sweating, he felt a drop run the small of his back, pause at the chain– “You must have been pretty enthusiastic—” and roll on.

Newboy turned to his drink. “Since Roger made the suggestion, and I gather you would like to go along with it, let me be perfectly honest: I enjoyed looking over your poems, I enjoyed your reading them to me; they have a sort of language that, from looking at the way you revise, at any rate, you’ve apparently done quite a bit of work to achieve. But I haven’t lived with them by any means long enough to decide whether they are, for want of a simple term, good poems. It’s very possible that if I just picked them up in a book store, and read them over, read them over very carefully too, I might easily not find anything in them at all that interested me.”

Kidd frowned.

“You say you’ve only been writing these for a few weeks?”

Kidd nodded, still frowning.

“That’s quite amazing. How old are you?”

“Twenty-seven.”

“Now there.” Mr. Newboy pulled back. “I would have thought you were much, much younger. I would have assumed you were about nineteen or eighteen and had worked most of your life in the country.”

“No. I’m twenty-seven and I’ve worked all over, city, country, on a ship. What’s that got to do with it?”

“Absolutely nothing.” Newboy laughed and drank. “Nothing at all. I’ve only met you a handful of times, and it would be terribly presumptuous of me to think I knew you, but frankly what I’ve been thinking about is how something like this would be for you. Twenty-seven…?”

“I’d like it.”

“Very good.” Newboy smiled. “And the decision I’ve come to is, simply, that so little poetry is published in the world it would ill behoove me to stand in the way of anyone who wants to publish more. Your being older than I thought actually makes it easier. I don’t feel quite as responsible. You understand, I’m not really connected with the whole business. The idea came from Mr. Calkins. Don’t let this make you think ill of me, but for a while I tried to dissuade him.”

“Because you didn’t think the poems were good enough?”

“Because Roger is not in the business of publishing poetry. Often unintentionally, he ends up in the business of sensationalism. Sensationalism and poetry have nothing to do with one another. But then, your poems are not sensational. And I don’t think he wants to make them so.”

“You know, I was just talking to another poet, I mean somebody who’s been writing a long time, and with a book and everything. He’s got poems in Poetry. And that other magazine…the New Yorker. Maybe Mr. Calkins would like to see some of his stuff too?”

“I don’t think so,” Mr. Newboy said. “And if I have one objection to the whole business, I suppose that’s it. What would you like for the name of your book?”

The muscles in Kidd’s back tightened almost to pain. As he relaxed them, he felt the discomfort in the gut that was emblematic of fear. His mind was sharp and glittery. He was as aware of the two men in leather talking in the corner, the woman in construction boots coming from the men’s room, of Fenster and Loufer still in their booth, of the bartender leaning on the towel against the bar, as he was of Newboy. He pulled the notebook into his lap and looked down at it. After the count of seven he looked up and said, “I want to call it—Brass Orchids.”

“Again?”

“Brass Orchids.”

“No ‘The’ or anything?”

“That’s right. Just: Brass Orchids.”

“That’s very nice. I like that. I—” Then Newboy’s expression changed; he laughed. “That really is nice! And you’ve got quite a sense of humor!”

“Yeah,” Kidd said. “Cause I think it takes some balls for me to pull off some shit like that. I mean, me with a book of poems?” He laughed too.

“Yes, I do like that,” Newboy repeated. “I hope it all works out well. Maybe my hesitations will prove unfounded after all. And any time you want to get us copies of the poems, in the next few days, that’ll be fine.”

“Sure.”

Newboy picked up his glass. “I’m going to talk to Paul Fenster over there for a while. He left Roger’s today and I’d like to say hello. Will you excuse me?”

“Yeah.” Kidd nodded after Newboy.

He looked at his notebook again. With his thumb, he nudged the clip on the pen out of the spiral where he had stuck it, and sat looking at the cover: click-click, click-click, click.

He lettered across the cardboard: Brass Orchids. And could hardly read it for dirt.

Brushing to the final pages (pausing at the poem called “Elegy” to read two lines, then hurrying past), he felt a familiar sensation: at the page where he’d been writing before, listening for a rhythm from his inner voice, he turned to strain the inner babble—

It hit like pain, was pain; knotted his belly and pushed all air from his lungs, so that he rocked on the stool and clutched the counter. He looked around (only his eyes were closed) taking small gulps. All inside vision blanked at images of glory, inevitable and ineffably sensuous till he sat, grinning and opened mouthed and panting, fingers pressing the paper. He tore his eyelids apart, the illusory seal, and looked down at the notebook. He picked up the pen and hastily wrote two lines till he balked at an unrevealed noun. Re-reading made him shake and he began automatically crossing out words before he could trace the thread of meaning from sound to image: he didn’t want to feel the chains. They drew across him and stung.

They carried pain and no solution for pain.

And incorrectly labeled it something else.

He wrote more words (not even sure what the last five were) when once more his back muscles sickled, his stomach tapped the bar edge, and inside the spheres of his eyes, something blind and luminous and terrifying happened.

Those women, he thought, those men who read me in a hundred years will…and no predicate fixed the fantasy. He shook his head and choked. Gasping, he tried to read what he had set down, and felt his hand move to X the banalites that leached all energy: “…pit…” There was a word (a verb!), and watched those either side suddenly take its focus and lose all battling force, till it was only flabby, and archaic. Write: he moved his hand (remember, he tried to remember, that squiggle is the letters “…tr…” when you go to copy this) and put down letters that approximated the sounds gnawing his tongue root. “Awnnn…” was the sound gushing from his nose.

Someday I am going to…it came this time with light; and the fear from the park, the recollections of all fear that stained and stained like time and dirt, page, pen, and counter obliterated. His heart pounded, his nose ran; he wiped his nose, tried to re-read. What was that squiggle that left the word between “…reason…” and “…pain…” indecipherable?

The pen, which had dropped, rolled off the counter and fell. He heard it, but kept blinking at his scrawl. He picked the notebook up, fumbled the cover closed, and the floor, hitting his feet, jarred him forward. “Mr. Newboy…!”

Newboy, standing by the booth, turned. “…yes?” His expression grew strange.

“Look, you take this.” Kidd thrust the notebook out. “You take this now…”

Newboy caught it when he let it go. “Well, all right—”

“You take it,” Kidd repeated. “I’m finished with it…” He realized how hard he was breathing. “I mean I think I’m finished with it now…so—” Tak looked up from his seat—“you can take it with you. Now.”

Newboy nodded. “All right.” After a slight pause, he pursed his lips: “Well, Paul. It was good seeing you. I’d hoped you’d have gotten up again. You must come sometime soon, before I leave. I’ve really enjoyed the talks we’ve had. They’ve opened up a great deal to me. You’ve told me a great deal, shown me a great deal, about this city, about this country. Bellona’s been very good for me.” He nodded to Tak. “Good meeting you.” He looked once more at Kidd, who only realized the expression was concern as Newboy—with the notebook under his arm—was walking away.

Tak patted the seat beside him.

Kidd started to sit; halfway, his legs gave and he fell.

“Another hot brandy for the kid here!” Tak hollered, so loud people looked. To Fenster’s frown, Tak simply shook his grimacing head: “He’s okay. Just had a rough day. You okay, kid?”

Kidd swallowed, and did feel a little better. He wiped his forehead (damp), and nodded.

“Like I was saying,” Tak continued, as blond arms with inky leopards set Kidd a steaming glass, “for me, it’s a matter of soul.” He observed Fenster across his knuckles, continuing from the interruption. “Essentially, I have a black soul.”

Fenster looked from the exiting Newboy. “Hum?”

“My soul is black,” Tak reiterated. “You know what black soul is?”

“Yeah, I know what black soul is. And like hell you do.”

Tak shook his head. “I don’t think you understand—”

“You can’t have one,” Fenster said. “I’m black. You’re white. You can’t have a black soul. I say so.”

Loufer shook his head. “Most of the time you come on pretty white to me.”

“Scares you I can imitate you that well?” Fenster picked up his beer, then put the bottle back down. “What is it that all you white men suddenly want to be—”

“I do not want to be black.”

“—what gives you a black soul?”

“Alienation. The whole gay thing, for one.”

“That’s a passport to a whole area of culture and the arts you fall into just by falling into bed,” Fenster countered. “Being black is an automatic cutoff from that same area unless you do some fairly fancy toe-in-the-door work.” Fenster sucked at his teeth. “Being a faggot does not make you black!”

Tak put his hands down on top of one another. “Oh, all right—”

“You,” Fenster announced to Loufer’s partial retreat, “haven’t wanted a black soul for three hundred years. What the hell is it that’s happened in the last fifteen that makes you think you can appropriate it now?”

“Shit.” Tak spread his fingers. “You take anything from me you want—ideas, mannerisms, property, and money. And I can’t take anything from you?”

“That you dare—” Fenster’s eyes narrowed—“express, to me, surprise or indignation or hurt (notice I do not include anger), because that is exactly what the situation is, is why you have no black soul.” Suddenly he stood—the red collar fell open from the dark clavicle—and shook his finger. “Now you live like that for ten generations, then come and ask me for some black soul.” The finger, pale nail on dark flesh, jutted. “You can have a black soul when I tell you you can have one! Now don’t bug me! I gotta go pee!” He pulled away from the booth.

Kidd sat, his fingertips tingling, his knees miles away, his mind so open that each statement in the altercation had seemed a comment to and/or about him. He sat trying to integrate them, while their import slipped from the tables of memory. Tak turned to him with a grunt, and with his forefinger hooked down the visor of his cap. “I have the feeling—” Tak nodded deeply—“that in my relentless battle for white supremacy I have, yet once again, been bested.” He screwed up his face. “He’s a good man, you know? Go on, drink some of that. Kid, I worry about you. How you feeling now?”

“Funny,” Kidd said. “Strange…okay, I guess.” He drank. His breath stayed in the top of his lungs. Something dark and sloppy rilled beneath.

“Pushy, self-righteous.” Tak was looking across to where Fenster had been sitting. “You’d think he was a Jew. But a good man.”

“You met him on his first day here too,” Kidd said. “You ever ball him?”

“Huh?” Tak laughed. “Not on your life. I doubt he puts out for anyone except his wife. If he has one. And even there one wonders. Anyplace he’s ever gone, I’ll bet he’s gotten there over the fallen bodies of love-sick faggots. Well, it’s an education, on both sides. Hey are you sure you didn’t take some pill you shouldn’t have, or something like that? Think back.”

“No, really. I’m all right now.”

“Maybe you want to come to my place, where it’s a little warmer, and I can keep an eye on you.”

“No, I’m gonna wait for Lanya.” Kidd’s own thoughts, still brittle and hectic, were rattling so hard it was not till fifteen seconds later, when Fenster returned to the table, he realized Tak had said nothing more, and was merely looking at the candlelight on the brandy.

Voiding his bladder had quenched Fenster’s heat. As he sat down, he said quite moderately, “Hey, do you see what I was trying to—”

Tak halted him with a raised finger. “Touché, man. Touché. Now don’t bug me. I’m thinking about it.”

“All right.” Fenster was appeased. “Okay.” He sat back and looked at all the bottles in front of him. “After this much to drink, it’s all anybody can ask.” He began to thumb away the label.

But Tak was still silent.

“Kidd—?”

“Lanya!”

2

Wind sprang in the leaves, waking her, waking him beneath her turning head, her moving hand. Memories clung to him, waking, like weeds, like words: They had talked, they had walked, they had made love, they had gotten up and walked again—there’d been little talk that time because tears kept rising behind his eyes to drain away into his nose, leaving wet lids, sniffles, but dry cheeks. They had come back, lay down, made love again, and slept.

Taking up some conversation whose beginnings were snarled in bright, nether memories, she said: “You really can’t remember where you went, or what happened?” She had given him time to rest; she was pressing again. “One minute you were at the commune, the next you were gone. Don’t you have any idea what happened between the time we got to the park and the time Tak found you wandering around outside—Tak said it must have been three hours later, at least!” He remembered talking with her, with Tak in the bar; finally he had just listened to her and Tak talk to each other. He couldn’t seem to understand.

Kidd said, because it was the only thing he could think: “This is the first time I’ve seen real wind here.” Leaves passed over his face. “The first time.”

She sighed, her mouth settling against his throat.

He tried to pull the corner of the blanket across his shoulders, grunted because it wouldn’t come, lifted one shoulder: it came.

The astounded eye of leaves opened over them, turned, and passed. He pulled his lips back, squinted at the streaked dawn. Dun, dark, and pearl twisted beyond the branches, wrinkled, folded back on itself, but would not tear.

She rubbed his shoulder; he turned his face up against hers, opened his mouth, closed it, opened it again.

“What is it? Tell me what happened. Tell me what it is.”

“I’m going…I may be flipping out. That’s what it is, you know?”

But he was rested: things were less bright, more clear. “I don’t know. But I may be…”

She shook her head, not in denial, but wonder. He reached between her legs where her hair was still swive-sticky, rubbed strands of it between his fingers. Her thighs made a movement to open, then to clamp him still. Neither motion achieved, she brushed her face against his hair. “Can you talk to me about it? Tak’s right—you looked like you were drugged or something! I can tell you were scared. Try to talk to me, will you?”

“Yeah, yeah, I…” Against her flesh, he giggled. “I can still screw.”

“Well, a lot, and I love it. But even that’s sort of…sometimes like instead of talking.”

“In my head, words are going on all the time, you know?”

“What are they? Tell me what they say.”

He nodded and swallowed. He had tried to tell her everything important, about the Richards, about Newboy. He said, “That scratch…”

“What?” she asked his lingering silence.

“Did I say anything?”

“You said, ‘The scratch,’”

“I couldn’t tell…” He began to shake his head. “I couldn’t tell if I said it out loud.”

“Go on,” she said. “What scratch?”

“John, he cut Milly’s leg.”

“Huh?”

“Tak’s got an orchid, a real fancy one, out of brass. John got hold of it, and just for kicks, he cut her leg. It was…” He took another breath. “Awful. She had a cut there before. I don’t know, I guess he gets his rocks off that way. I can understand that. But he cut—”

“Go on.”

“Shit, it doesn’t make any sense when I talk about it.”

“Go on.”

“Your legs, you don’t have any cut on them.” He let the breath out; and could feel her frowning down in her chest. “But he cut hers.”

“This was something you saw?”

“She was standing up. And he was sitting down. And suddenly he reached over and just slashed down her leg. Probably it wasn’t a very big cut. He’d done it before. Maybe to someone else. Do you think he ever did it to anyone else—?”

“I don’t know. Why did it upset you?”

“Yes…no, I mean. I was already upset. I mean because…” He shook his head. “I don’t know. It’s like there’s something very important I can’t remember.”

“Your name?”

“I don’t even…know if that’s it. It’s just—very confusing.”

She kept rubbing till he reached up and stopped her hand.

She said: “I don’t know what to do. I wish I did. Something’s happening to you. It’s not pretty to watch. I don’t know who you are, and I like you a lot. That doesn’t make it easier. You’ve stopped working for the Richards; I’d hoped that would take some pressure off. Maybe you should just go away; I mean you should leave…”

In the leaves, the wind walked up loudly. But it was his shaking head that stopped her. Loudly wind walked away.

“What were they…why were they all there? Why did you take me there?”

“Huh? When?”

“Why did you take me there tonight?”

“To the commune?”

“But you see, you had a reason, only I can’t understand what it was. It wouldn’t even matter.” He rubbed her cheek until she caught his thumb between her lips. “It wouldn’t matter.” Diffused anxiety hardened him and he began to press and press again at her thigh.

“Look, I only took you there because—” and the loud wind and his own mind’s tumbling blotted it. When he shook his head and could hear again, she was stroking his thick hair and mumbling, “Shhhhh…Try and relax. Try and rest now, just a little…” With her other hand, she pulled the rough blanket up. The ground was hard under shoulder and elbow.

He propped himself on them while they numbed, and tried out memory.

Suddenly he turned to face her. “Look, you keep trying to help, but what do you…” He felt all language sunder on silence.

“But what do I really feel about all this?” she saved him. “I don’t know—no, I do.” She sighed. “Lots of it isn’t too nice. Maybe you’re in really bad shape, and since I’ve only known you for a little while, I should get out now. Then I think, Hey, I’m into a really good thing; if I worked just a little harder I might be able to do something that would help. Sometimes, I just feel that you’ve made me feel very good—that one hurts most. Because I look at you and I see how much you hurt and I can’t think of anything to do.”

“He…” he dredged from flooded ruins, “I…don’t know.” He wished she would ask what he meant by “he,” but she only sighed on his shoulder. He said, “I don’t want to scare you.”

She said, “I think you do. I mean, it’s hard not to think you’re just trying to get back at me for something somebody else did to you. And that’s awful.”

“Am I?”

“Kidd, when you’re off someplace, working, or wandering around, what do you remember when you remember me?”

He shrugged. “A lot of this. A lot of holding each other, and talking.”

“Yeah,” and he heard a smile shape her voice, “which is a lot of the most beautiful part. But we do other things. Remember those too. That’s cruel of me to ask when you’re going through this, isn’t it? But there’s so much you don’t see. You walk around in a world with holes in it; you stumble into them; and get hurt. That’s cruel to say, but it’s hard to watch.”

“No.” He frowned at the long dawn. “When we went up to see New-boy, did you like—” and remembered her ruined dress while he said: “At Calkins’—did you have fun?”

She laughed. “You didn’t?” Her laugh died.

Still, he felt her smile pressed on his shoulder. “It was strange. For me. It’s easy sometimes to forget I’ve got anything to do other than…well, this.”

“You talked about an art teacher once. I remember that. And the tape editing and the teaching. You paint too?”

“Years ago,” she countered. “When I was seventeen I had a scholarship to the Art Students’ League in New York, five, six years back. I don’t paint now. I don’t want to.”

“Why’d you stop?”

“Would you like to hear the story? Basically, because I’m very lazy.” She shrugged in his arms. “I just drifted away from it. When I was drifting, I was very worried for a while. My parents hated the idea of my living in New York. I had just left Sarah Lawrence—again—and they wanted me to stay with a family. But I was sharing an awful apartment on Twenty-Second Street with two other girls and going part time to the League. My parents thought I was quite mad and were very happy when I wanted to go to a psychiatrist about my ‘painting block.’ They thought he would keep me from doing anything really foolish.” She barked a one-syllable laugh. “After a while, he said what I should do is set myself a project. I was to make myself paint three hours each day—paint anything, it didn’t matter. I was to keep track of the time in a little twenty-five cent pad. And for every minute under three hours I didn’t paint, I had to spend six times that amount of time doing something I didn’t like—it was washing dishes, yes. We had decided that I had a phobia against painting, and my shrink was behaviorist. He was going to set up a counter unpleasantness—”

“You had a phobia about dishwashing too?”

“Anyway.” She frowned at him in the near dark. “I left his office in the morning and got started that afternoon. I was very excited. I felt I might get into all sorts of areas of my unconscious in my painting that way…whatever that meant. I didn’t fall behind until the third day. And then only twenty minutes. But I couldn’t bring myself to do two hours of dishwashing.”

“How many dishes did you have?”

“I was supposed to wash clean ones if I ran out of dirty ones. The next day I was okay. Only I didn’t like the painting that was coming out. The day after that I don’t think I painted at all. That’s right, somebody came over and we went up to Poe’s Cottage.”

“Ever been to Robert Louis Stevenson’s house in Monterey?”

“No.”

“He only rented a room in it for a couple of months and finally got thrown out because he couldn’t pay the rent. Now they call it Stevenson’s House and it’s a museum all about him.”

She laughed. “Anyway, I was supposed to see the doctor the next day. And report on how it was going. That night I started looking at the paintings—I took them out because I thought I might make up some work time. Then I began to see how awful they were. Suddenly I got absolutely furious. And tore them up—two big ones, a little one, and about a dozen drawings I’d done. Into lots of pieces. And threw them away. Then I washed every dish in the house.”

“Shit…” He frowned at the top of her head.

“I think I did some drawing after that, but that’s more or less when I really stopped painting. I realized something though—”

“You shouldn’t have done that,” he interrupted. “That was awful.”

“It was years ago,” she said. “It was sort of childish. But I—”

“It frightens me.”

She looked at him. “It was years ago.” Her face was greyed in the grey dawn. “It was.” She turned away, and continued. “But I realized something. About art. And psychiatry. They’re both self-perpetuating systems. Like religion. All three of them promise you a sense of inner worth and meaning, and spend a lot of time telling you about the suffering you have to go through to achieve it. As soon as you get a problem in any one of them, the solution it gives is always to go deeper into the same system. They’re all in a rather uneasy truce with one another in what’s actually a mortal battle. Like all self-reinforcing systems. At best, each is trying to encompass the other two and define them as sub-groups. You know: religion and art are both forms of madness and madness is the realm of psychiatry. Or, art is the study and praise of man and man’s ideals, so therefore a religious experience becomes just a brutalized aesthetic response and psychiatry is just another tool for the artist to observe man and render his portraits more accurately. And the religious attitude I guess is that the other two are only useful as long as they promote the good life. At worst, they all try to destroy one another. Which is what my psychiatrist, whether he knew it or not, was trying, quite effectively, to do to my painting. I gave up psychiatry too, pretty soon. I just didn’t want to get all wound up in any systems at all.”

“You like washing dishes?”

“I haven’t had to in a long, long time.” She shrugged again. “And when I have to now, actually I find it rather relaxing.”

He laughed. “I guess I do too.” Then: “But you shouldn’t have torn up those paintings. I mean, suppose you changed your mind. Or maybe there was something good in them that you could have used later—”

“It was bad if I wanted to be an artist. But I wasn’t an artist. I didn’t want to be.”

“You got a scholarship.”

“So did a lot of other people. Their paintings were terrible, mostly. By the laws of chance, mine were probably terrible too. No, it wasn’t bad if I didn’t want to paint at all.”

But he was still shaking his head.

“That really upsets you, doesn’t it? Why?”

He took a breath and moved his arm from under her. “It’s like everything you—anybody says to me…it’s like they’re trying to tell me a hundred and fifty other things as well. Besides what they’re saying direct.”

“Oh, perhaps I am, just a bit.”

“I mean, here I am, half nuts and trying to write poems, and you’re trying to tell me I shouldn’t put my faith in art or psychiatry.”

“Oh no!” She folded her hands on his chest, and put her chin there. “I’m saying I decided not to. But I wasn’t nuts. I was just lazy. There is a difference, I hope. And I wasn’t an artist. A tape editor, a teacher, a harmonica player, but not an artist.” He folded his arms across her neck and pushed her head flat to its cheek. “I suppose the problem,” she went on, muffled in his armpit, “is that we have an inside and an outside. We’ve got problems both places, but it’s so hard to tell where the one stops and the other takes up.” She paused a moment, moving her head. “My blue dress…”

“That reminds you of the problem with the outside?”

“That, and going up to Calkins’. I don’t mind living like that—every once in a while. When I’ve had the chance, I’ve always done it rather well.”

“We could have a place like Calkins’. You can have anything you want in this city. Maybe it wouldn’t be as big, but we could find a nice house; and I could get stuff like everybody else does. Tak’s got an electric stove that cooks a roast beef in ten minutes. With microwaves. We could have anything—”