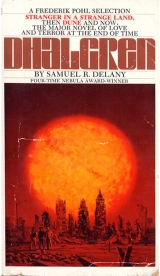

Текст книги "Dhalgren"

Автор книги: Samuel R. Delany

Соавторы: Samuel R. Delany

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 54 (всего у книги 60 страниц)

One of the things that also went down in the discussion was an argument about getting food, which I guess was really what started the whole thing, and this other part just came up; but my mind follows funny tracks.

It had to do with the differences (and similarities) between the girls who were scorpions and the girls who just hung around with us. With reference to the guys who were members and the guys who just hung. It was a good discussion to have and a dull one to reconstruct. And I guess it was mainly for Mike’s benefit anyway (Mike is one of said guys who hangs, a long-haired friend of Devastation’s; sleeps here most of the time but also doesn’t want to join) and I guess/think/suspect one difference between members and non-members anyway is that members know the difference already and don’t have to talk about them (that politeness again) though from some of the things Tarzan says, I wonder.

an intercallory jamb between Wednesday and the twenty-second, bless. Grain, blabbed on slip-time, told its troubles to the tree (all runny in the oozy gyre’s incarnadine). She won’t run Thursdays. The underside of the little hand is tarnished; why is muk-amuk canonized so easy? Truck-tracks crow-foot creators drooling half-and half. She didn’t remember how or when, last time. Pavement sausages split; the cabbage remembers. Lions with prehensile eyes pick up their paws, apocopate, and go to town. Get with-it, mauve-peanut! Make it, thing-a-ma-boob! You won’t catch me slipping my sticktoitiveness under your smorgasborg. Fondle my nodule, love my dog. Lilting is all is easy. Knitting needles receed around the vision, baring his curviture, clearing her underwear. So that’s not what it’s for. French fried pickelilly and deep-dish-apple death won’t get you through that wake up in the morning alive. Your rosamundus may mathematik him, but it won’t move me one mechanical apple corer. I have come to to wound the autumnal city: the other side of the question is a mixed metaphor if I ever heard one. Timed methods run out: coo, morning bird. I could stop before breathing marble basonets. Salvage a disjuncture, it’s all you Middle of the ring around the Harley Davidson bush, blooming, blooming, shame, socks, dearth and passion pudding, flowers, or Ms. Crystaline Pristine. Her backwoods mystification is citified in the face. Pentacle pie and hunger city, oh my oh too much, my meat and mashed potatoes pansy, my in the middle of it biche.

Hart’s blood is good fly-catching bait. So’s fresh sheep-shit. Blatting about in the empty aurical, you think Atocha is in Madrid, what about 92nd Street, or what she told me of St. Croix? She isn’t your running the mill broad loom, sword, or side. She’s right on the guache circuit where a principle’s a principle with all hell lined up to get paid. Maundy, Tributary, Whitstanley, Horripilation, Factotum, Susquahanna, Summer-fine day. It’s all the same in the bitch’s kitchen. You look for the dice this time. Maybe you can wind up a winner. Summary, Mopery, Titular, Wisdom, Thaumaturgy, Fictive, Samoa and five hands over. When I grow up I’m going to get a vasectomy all my own. (A dendrite in the glans is worthy of the bush.) Why does he insist on winter all the time? You can stutter in the water but that’s not the way to think. Not thinking but the way thinking feels. Not knowledge but knowledge’s form. If there’s enough raisins, splay feet, and guilded hornet-heads, you can wish, dream, lie like a Saxon though you only prevaricate like a Virginia ham. George! the ingenuity I’ve expended to fill five missing days.

Conversation with furry Forest at Teddy’s:

“What are you writing now?”

“I’m not writing anything,” I said. “I haven’t been writing anything and I’m not going to write anything.”

He frowned, and I hoped a lot the lie had at least the structure of truth. But how can it? Which is why I haven’t been able to write anything but this journal in so long. And thank the blinded stars, I feel the energies for that going.

What other days from my life have gone? After a week, I can’t remember five. After a year, how many days in it will you never think of again?

But Faust was walking ahead between the shadowed presses. “Here,” he said. “This is what you want to see, isn’t it?”

I stepped up to the work table. Battleship linoleum glittered with lead shavings.

“There.” He pointed at a full-page tray of type with a yellow index nail.

Raised grey-on-grey proclaimed:

“But…?”

“That’s you, ain’t it?” His cackle echoed among the ceiling pipes.

“But I haven’t given Calkins the second collection! He doesn’t even know there is one!”

“Maybe he’s just making a good guess.”

“But I don’t want him to—”

“They’re supposed to got obituaries too, prepared on all the famous people around here who might die.”

“Oh, come on,” I said. “Let’s get out of here.”

“You keep askin’ me to show you where they printed the thing…”

I started away from the desk. “But I don’t see any rolls of paper around. The presses aren’t going. You mean a thirty-six-page newspaper comes out of here every day?”

But Faust was already walking away, still chuckling, his white hair—sides, beard, and back—covering the bright choker.

“Joaquim?” I called. “Joaquim, when do they actually print it? I mean this doesn’t look like anybody’s been in here since before the

going out along Broadway. The smoke was as bad as I’ve ever seen it—rolling from side-alleys, gauzing the streets in loose layers. Down one block, the face on an eight-(I counted)-story building was curtained with it, leaking out broken windows, to waterfall to the street, mounded and shifting.

One section of pavement had been replaced by metal plates (some incomplete repair) clanging when I crossed. After another half hour the buildings were taller and the street was wider and the sky grey and streaked like weathered canvas, like silvered velvet.

On the wide steps to a black and glass office building was a fountain. I went up to examine: Wet patches of color on the dusty mosaic at the bottom; rust around the pentangle of nozzles on the cement ball; I climbed over the lip to look in what I guessed had held plants: dried stem stumps poked from ashy earth; beer and soda-can tabs. I stepped once on a wet patch of green and yellow mosaic tiles with my bare foot; took my foot away and left a chalky print.

The bus came around the corner. It didn’t scare me this time. I vaulted the fountain edge and sprinted down the steps.

He feels the experience whose detritus is interleaved in the Orchids’ pages/petals has left him a perfect voice with which he can say nothing; he can imagine nothing duller. (For that sentence to make sense, it must be ugly as possible. And it isn’t—quite. So it fails.

The doors flap-clapped open even before it stopped.

“Hey,” I called. “How far up Broadway do you go?”

Do you know the expression on somebody’s face when you wake them out of a sound sleep with something serious, like a fire or a death? (Small, bald, oyster-eyed black man, obsessed and trundling his bus from here to there.) “How far you going?”

I told him: “Pretty far.”

While he considered how far that was, I got on. Then we both thought about the last time I was on his bus; I don’t know if the little movement of his head back into the khaki collar acknowledged that or not. But I’m sure that’s what we were thinking. I also thought: There are no other passengers.

He closed the doors.

I sat behind him, looking at the broad front window as we shook on up the street.

A sound made me look back.

All the advertising cards had been filled with posters, or sections from posters, of George. From over the window his face looked down there; here were his knees. The long one over the back door showed his left leg, horizontal, foot to mid-thigh. A third of them were crotch-shots.

The sound again; so I got up and handed myself down the aisle, bar after bar. The old man—pretending to sleep—was so slumped in the back seat I couldn’t see him till I passed the second door. One brown and ivory eye opened over his frayed collar slanting across the black wrinkle of an ear. He closed it again, turned away, and made that strangling moan—the sound, again, that till now I had suspected was something strained and complaining in the engine.

I sat, bare foot on the warm wheel case, boot on the bar below the seat in front. The smoke against the glass was fluid thick; runnels wormed the pane. Thinking (complicated thoughts): Life is smoke; the clear lines through it, encroached on and obliterated by it, are poems, crimes, orgasms—carried this analogy to every jounce and jump of the bus, ripple on the glass, even noticing that through the windows across the aisle I could see a few buildings.

The falsification of this journal: First off, it doesn’t reflect my daily life. Most of what happens hour by hour here is quiet and dull. We sit most of the time, watch the dull sky slipping. Frankly, that is too stupid to write about. When something really involving, violent, or important happens, it occupies too much of my time, my physical energy, and my thought for me to be able to write about. I can think of four things that have happened in the nest I would like to have described when they occurred, but they so completed themselves in the happening that even to refer to them seems superfluous.

What is down, then, is a chronicle of incidents with a potential for wholeness they did not have when they occurred; a false picture, again, because they show neither the general spread of our life’s fabric, nor the most significant pattern points.

To show the one is too boring and the other too difficult. That is probably why (as I use up more and more paper trying to return the feeling I had when I thought I was writing poems) I am not a poet…anymore? The poems perhaps hint it to someone else, but for me they are dry as the last leaves dropping from the burned trees on Brisbain. They are moments when I had the intensity to see, and the energy to build, some careful analog that completed the seeing.

They stuck at me for two weeks? For three?

I don’t really know if they occurred. That would take another such burst. All I have been left is the exhausting habit of trying to tack up the slack in my life with words.

The bus stopped. The driver twisted around; for a moment I thought he was speaking to the old man behind me: “I can’t take you no farther,” gripping the bar across the back of the driver’s seat, elbow awkward in the air. “I got you past the store.” He pauses significantly; I wish he hadn’t. “You’ll be all right.”

Behind me the old man sniffled and shifted.

I stood up and, under George’s eyes (and knees and hands and left foot and right tit), stepped on the treadle. The doors opened. I got out on the curb.

The pavement was shattered about a hydrant, which leaned from its pipes. I turned and watched the bus turn.

From the doorway at the end of the block a man stepped. Or a woman. Whoever it was, anyway, was naked. I think.

I walked in that direction. The figure went back in. What I passed was a florist’s smashed display window. At first I was surprised at all the greenery on the little shelves up the side. But they were plastic—ferns, leaves, shrubs. Three big pots in the center only had stumps. Back, in the shadow, by the aluminum frame on the glass door of the refrigerator, something big, fetid, and wet moved. I only saw it a second when I hurried by. But I got goose bumps.

The reason the bus driver hadn’t wanted to go on was that Broadway grew ornate scrolled railings on either side and soared over train tracks forty feet down a brick-walled canyon. A few yards out, a twelve foot hunk of paving had fallen off, as though a gap-tooth giant had bitten it away. The railing twisted off both sides of the gash. From the edge, looking down, I couldn’t see where any rubble had landed.

Beyond the overpass, to the left, a rusted wire fence ran before some trees; through the trees, I saw water patched with ash. To the right, up a slope blotched with grass, was the monastery.

Like that.

I walked up the steps between the beige stones. Halfway, I looked back across the road.

Smoke reeds grew from the woods and clotted waters to bloom and blend with the sky.

I reached the top of the steps with the strangest sense of relief and anticipation. The simple journey was the resolve that till now I’d thought suspended. The monastery was several three-story buildings. A tower rose behind the biggest. I put my hands in my pockets, feeling my leg muscles move as I walked; one finger went through a hole.

Thinking: You arrive at a monastery halfway through a round of pocket-pool. Sure. I relaxed my stomach (it had tightened in the climb) and ambled, breathing loudly, over the red and grey flags. Between dusty panes, putty blobbed the leaded tessellations. At the same moment I decided the place was deserted, a man in a hood and robe stepped around the corner and peered.

I took my hands out of my pockets.

He folded his over his lap and came forward. They were big, and translucent. The white-and-black toes of very old basketball sneakers poked alternately from his hem. His eyes were grey. His smile looked like the amphetamine freeze on a particularly pale airline stewardess. His hood was back enough to see his skull was white as bread dough. A sore, mostly hidden, like an eccentric map, was visible under the hood’s edge: wet, raised, with purple bits crusted inside it and yellow flaking around it. “Yes?” he asked. “Can I help you?”

I smiled and shrugged.

“I saw you coming up the steps and I was wondering if there was anything I could do for you, anyone in particular you wanted to see?”

“I was just looking around.”

“Most of the grounds are in the back. We don’t really encourage people to just wander about, unless they’re staying. Frankly, they’re not in such hot shape right through here. The Father was talking yesterday at the morning meal about starting a project to put them back in order. Everybody was delighted to get a place right across from Holland Lake—” He nodded toward the other side of the road. “But now look at it.”

When I turned back from the lacustrine decay, he was pulling his hood further down his forehead with thick thumb and waxy forefinger.

I looked around at the buildings. I’d been trying to find this place so long; but once found, the search seemed so easy. I was off on some trip about—

“Excuse me,” he said.

–and came back.

“Are you the Kid?”

I felt a good feeling in my stomach and a strong urge to say No. “Yeah.”

His chin and his smile twisted in a giggle without sound. “I thought you might be. I don’t know why I thought so, but it seemed a reasonable guess. I mean I’ve seen pictures of…scorpions—in the Times. So I knew you were one of them, but I had no way of knowing which one. That you were the…” and shook his head, a satisfied man. “Well.” He folded his hands. “We’ve never been visited by any scorpions before, so I just took a guess.” His wrinkleless face wrinkled. “Are you sure you weren’t looking for someone?”

“Who’s here to look for?”

“Most people who come usually want to see the Father—but he’s closeted with Mr. Calkins now, so that would be unfeasible today—unless of course you wanted to wait, or come back at some other—”

“Is Mr. Calkins here?” In my head I’d been halfway through an imaginary dialogue which had begun when I’d answered his first question with: The Kid? Who, me? Naw…

“Yes.”

“Could I see him?” I asked.

“Well, I don’t…as I said, he’s closeted with the Father.”

“He’d want to see me,” I said. “He’s a friend of mine.”

“I don’t know if I ought to disturb them.” His smile fixed some emotion I couldn’t understand till he spoke: “And I believe one of the reasons Mr. Calkins came here was to put some of his friends at a more comfortable distance.” Then he giggled. Out loud.

“He’s never met me,” I said and wondered why. (To explain that the personal reasons which make you want to put friends at a distance had nothing to do with Calkins and me? But that’s not what it sounded like.) I let it go.

A bell bonged.

“Oh, I guess—” he glanced at the tower—“Sister Ellen and Brother Paul didn’t forget after all,” and smiled (at some personal joke?) while I watched a model of the monastery I didn’t even realize I’d made—the three buildings inhabited solely by the Father, Calkins, and this one here—break down and reassemble into: a community of brothers and sisters, a small garden, goats and chickens, matins, complines, vespers…

“Hey,” I said.

He looked at me.

“You go tell Mr. Calkins the Kid is here, and find out if he wants to see me. If he doesn’t, I’ll come back some other time—now that I know where this place is.”

He considered, unhappily. “Well, all right.” He turned.

“Hey.”

He looked back.

“Who are you?”

“Randy…eh, Brother Randolf.”

“Okay.”

He went off around the corner, with the echo of the bell.

Beneath the chipped keystone the arched door looked as though (a slough of rust below the wrist-thick bolt) it hadn’t been opened all year.

And I got back on my trip: I had looked so long for this place; finding it had been accomplished with no care for the goal itself. For minutes I wondered if I couldn’t get everything in my life like that. When I finally worked out a sane answer (“No.”), I laughed (aloud) and felt better.

“They’re all—”

I turned from the miasmas of Holland Lake.

“—all finished for the afternoon,” Brother Randy said from the corner. “He’ll talk with you. Mr. Calkins said he’ll talk with you a little while. The Father says it’s all right.” (I started toward him and he still said:) “You just come with me.” I think he was surprised it had worked out like that. I was surprised too; but he was unhappy about it.

“Here,” was a white wood lawn chair on a stone porch with columns, along the side of the building.

I sat and gave him a grin.

“They’re finished, you see,” he offered. “For the afternoon. And the Father says it’s all right for him to talk now, if it isn’t for too long.”

I think he wanted to smile.

I wonder if that thing up under his hood hurt.

“Thanks,” I said.

He left.

I looked around the patchy grass, up and down the porch, at the beige stone; inset beside me in the wall was a concrete grill, cast in floral curls. Once I stood up and looked through it close. Another grill behind it was set six inches out of alignment, so you couldn’t see inside. I was thinking it was probably for ventilation, when my knee (as I moved across the stone flowers trying to see) hit the chair and the feet scraped, loudly.

“Excuse me…?”

I pulled back a few inches. “Hello?” I said, surprised.

“I didn’t realize you were out there yet—until I heard you move.”

“Oh.” I stepped back from the grill. “I thought you were going to come out here on the porch…” (He chuckled.) “Well, I guess this is okay.” I pulled my chair around.

“Good. I’m glad you find this acceptable. It’s rather unusual for the Father to allow someone seeking an understanding of the monastic community—as they describe the process here—to have any intercourse at all with people outside the walls. Converse with members is limited. But though I’ve been here several days, I don’t officially start my course of study till sundown this evening. So he’s made an exception.”

I sat on the arm of the lawn chair. “Well,” I said, “if it goes down this evening…”

He chuckled again. “Yes. I suppose so.”

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

“I guess the best way to describe it is to say that I’m about to embark on a spiritual course of study. I’m not too sure how long it will last. You catch me just in time. Oh—I must warn you: You may ask some questions that I’m not allowed to answer. I’ve been instructed by the Father that, when asked them, I am simply to remain silent until you speak again.”

“Don’t worry,” I said, “I won’t pry into any secrets abut your devotional games here,” wishing I sort of could.

But the voice said: “No, not questions that have anything to do with the monastery.”

And (While he considered further explanation?) I considered the tower exploding slowly, thrusting masonry on blurred air too thin to float brick and bolts and bellrope.

“I don’t think there’s anything about the monastery you could ask I wouldn’t be allowed to answer—if I know the answers. But part of the training is a sort of self-discipline: Any questions that sparks certain internal reactions in me, causes me to think certain thoughts, to feel certain feelings, rather than rush into some verbal response that, informative or not, is still put up mainly to repress those thoughts and feelings, I’m supposed to experience them fully in the anxiety of silence.”

“Oh,” I said. “What sort of thoughts and feelings?” After ten quiet seconds, I laughed. “I’m sorry. I guess that’s sort of like not thinking about the white hippopotamus when you’re changing the boiling water into gold.”

“Rather.”

“It sounds interesting. Maybe I’ll try it some day,” and felt almost like I did the morning I’d told Reverend Amy I’d drop in on one of her services. “Hey, thanks for the note. Thanks for the party, too.”

“You’re most welcome. If you got my letter, then I must restrain from apologizing anymore. Though I’m not surprised at meeting you, I wasn’t exactly expecting it now. Dare I ask if you enjoyed yourself—though perhaps it’s best just to let it lie.”

“It was educational. But I don’t think it had too much to do with your not showing up. All the scorpions had a good time—I brought the whole nest.”

“I should like to have been there!”

“Everybody got drunk. The only people who didn’t enjoy themselves probably didn’t deserve to. Didn’t you get any reports back from your friends?” First I thought I’d asked one of those questions.

“…Yes…Yes, I did. And some of my friends are extremely colorful gossips—sometimes I wonder if that’s not how I chose them. I trust nothing occurred to distract you from any writing you’re engaged in at present. I was quite sincere about everything I said concerning your next collection in my letter.”

“Yeah.”

“After some of my friends—my spies—finished their account of the evening, Thelma—do you remember her?—said practically the same thing you just did, almost word for word, about anyone who didn’t enjoy himself not deserving to. When she said it, I suspected she was just trying to make me feel better for my absence. But here it is, corroborated by the guest of honor. I best not question it further. I hadn’t realized you were a friend of Lanya’s.”

“That’s right,” I said. “She used to know you.”

“An impressive young lady both then and, apparently, from report, now. As I was saying, after my spies finished their account, I decided that you are even more the sort of poet Bellona needs than I’d thought before, in every way—except in literary quality which, as I explained in my letter, I am, and intend to remain, unfit to judge.”

“The nicest way to put it, Mr. Calkins,” I said, “is I’m just not interested in the ways you mean. I never was interested in them. I think they’re a load of shit anyway. But…”

“You are aware,” he said after my embarrassed silence, “the fact that you feel that way makes you that much more suited for your role in just the ways I mean. Every time you refuse another interview to the Times, we shall report it, as an inspiring example of your disinterest in publicity, in the Times. Thus your image will be further propagated—Of course you haven’t refused any, up till now. And you said ‘But…’” Calkins paused. “‘But’ what?”

I felt really uncomfortable on the chair arm. “But…I feel like I may be lying again.” I looked down at the creases of my belly, crossed with chain.

If he picked up on the “again” he didn’t show it. “Can you tell me how?”

“I remember…I remember a morning in the park, before I ever met Mr. Newboy or even knew anyone would ever want to publish anything I ever wrote, sitting under a tree—bare-ass, with Lanya asleep beside me, and I was writing—no, I was re-copying out something. Suddenly I was struck with…delusions of grandeur? The fantasies were so intense I couldn’t breathe! They hurt my stomach. I couldn’t…write! Which was the point. Those fantasies were all in the terms you’re talking about. So I know I have them…” I tried to figure why I’d stopped. When I did, I took a deep breath: “I don’t think I’m a poet…anymore, Mr. Calkins. I’m not sure if I ever was one. For a couple of weeks, once, I might have come close. If I actually was, I’ll never know. No one ever can. But one of the things I’ve lost as well, if I ever had it, is the clear knowledge of the pitch the vanes of my soul could twist to. I don’t know…I’m just assuming you’re interested in this because in your letter you mentioned wanting another book.”

The advantage of transcribing your own conversation: It’s the only chance you have to articulate. This conversation must have been five times as long and ten times as clumsy. Two phrases I really did lift, however, are the one about “… the clear knowledge of the pitch the vanes of my soul could twist to …” and “…experience them in the anxiety of silence …” Only it occurs to me “the vanes of my soul …” was his, while “… the anxiety of silence …” was mine.

“My interest,” he said, coldly, “is politics. I’m only out to examine that tiny place where it and art are flush. You make the writer’s very common mistake: You assume publishing is the only political activity there is. It’s one of my more interesting ones; it’s also one of my smallest. It suffers accordingly, and there’s nothing either of us can do about it with Bellona in the shape it is. Then again, perhaps I make a common mistake for a politician. I tend to see all your problems merely as a matter of a little Dichtung, a little Wahrheit, with the emphasis on the latter.” He paused and I pondered. He came up with something first: “You say you’re not interested in the extra-literary surroundings of your work—I take it we both refer to acclaim, prestige, the attendant hero-worship and its inevitable distortions—all those things, in effect, that buttress the audience’s pleasure in the artist when the work itself is wanting. Then you tell me that, actually, you’re no longer interested in the work itself—how else am I to interpret such a statement as ‘I am no longer a poet’? Tell me—and I ask because I am a politician and I really don’t know—can an artist be truly interested in his art and not in those other things? A politician—and this I’ll swear—can not be truly (better say, effectively) interested in his community’s welfare without at least wanting (whether he gets it or not) his community’s acclaim. Show me one who doesn’t want it (whether he gets it or not) and I’ll show you someone out to kill the Jews for their own good or off to conquer Jerusalem and have it dug up as a reservoir for holy water.”

“Artists can,” I said. “Some very good emperors have been the patrons of some very good poets. But a lot more good poets seem to have gotten by without patronage from any emperors at all, good, bad, or otherwise. Okay: a poet is interested in all those things, acclaim, reputation, image. But as they’re a part of life. He’s got to be a person who knows what he’s doing in a very profound way. Interest in how they work is one thing. Wanting them is another thing—the sort of thing that will mess up any real understanding of how they work. Yes, they’re interesting. But I don’t want them.”

“Are you lying?—‘again,’ as you put it. Are you fudging?—which is how I’d put it.”

“I’m fudging,” I said. “But then…I’m also writing.”

“You are? What a surprise after all that! Now I’ve certainly read enough dreadful things by men and women who once wrote a work worth reading to know that the habit of putting words on paper must be tenacious as the devil—But you’re making it very difficult for me to maintain my promised objectivity. You must have realized, if only from my euphuistic journalese, I harbor all sorts of literary theories—a failing I share with Caesar, Charlemagne, and Winston Churchill (not to mention Nero and Henry the Eighth): Now I want to read your poems from sheer desire to help! But that’s just the point where politics, having convinced itself its motives are purely benevolent, should keep its hands off, off, off! Why are you dissatisfied?”

I shrugged, realized he couldn’t see it, and wondered how much of him I was losing behind the stonework. “What I write,” I said, “doesn’t seem to be…true. I mean I can model so little of what it’s about. Life is a very terrible thing, mostly, with points of wonder and beauty. Most of what makes it terrible, though, is simply that there’s so much of it, blaring in through the five senses. In my loft, alone, in the middle of the night, it comes blaring in. So I work at culling enough from it to construct moments of order.” I meshed my fingers, which were cool, and locked them across my stomach, which was hot. “I haven’t been given enough tools. I’m a crazy man. I haven’t been given enough life. I’m a crazy man in this crazed city. When the problem is anything as complicated as one word spoken between two people, both suspecting they understand it…When you touch your own stomach with your own hand and try to determine who is feeling who…When three people put their hands over my knee, each breathing at a different rate, the heartbeat in the heel of the thumb of one of them jarring with the pulse in the artery edging the bony cap, and one of them is me—what in me can order gets exhausted before it all.”

“You’re sure you’re not simply telling me—Oh, I wish I could see you!—or avoiding telling me, that the responsibilities of being a big, bad scorpion are getting in the way of your work?”

“No,” I said. “More likely the opposite. In the nest, I’ve finally got enough people to keep me warm at night. And I can feel safe as anyone in the city. Any scorpions who think about my writing at all are simply dazzled by the object—the book you were nice enough to have it made into. A few of them even blush when descriptions of them show up in it. That leaves what actually goes on between the first line and the last entirely to me. The scorpions caught me without a fight. My mind is a magnet and they’re filings in a field I’ve made—No, they’re the magnets. I’m the filing, in a stable position now.”