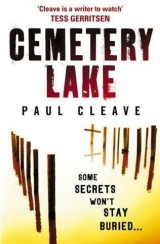

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter twenty-four

At four in the morning I give up on sleep and sit at the table drinking coffee. I keep going over what I’ve just done, as if by picturing each detail there might still be the chance to go back and change it.

Two years ago, after I spoke to Quentin James, I slept like the dead. I got home and made some dinner, I watched some TV,

and an hour after midnight I went to bed. It was a new day and I was a new man, and when I slipped between the sheets I closed my eyes and pictured my family and I fell asleep. There were no nightmares. No questions. No guilt.

But not this time.

I drive back to the cemetery. The night is cold and daylight is still a few hours away. On the way I throw yesterday’s clothes into a dumpster, just as hundreds of guilty men before me have done.

At the gravesite where Henry Martins was dug up I stand next

to the corner of the lake and I think about the choices that have made me who I am. Then I realise they were choices made for

me. Quentin James started me down this road. He gave me no

option but to drive him out to the middle of nowhere and leave him behind. What else could I have done? Let him serve his time in jail so he could kill again when they set him free? Fuck those people who think that alcoholism is a disease. Cancer is a disease.

Tell people with cancer that alcoholism is a disease and see what their views are. It’s all about choice. People choose to drink.

They don’t choose to get leukaemia. So James had only himself

to blame. He chose to keep drinking. He could have chosen to

stop. Could have chosen to get help. He chose the path I took

him down.

I kick a clump of dirt into the water and watch it disappear.

Do I have limits? Do I kill the next person I suspect is a murderer?

Hell, what about the next time I have to stand in line somewhere and I get sick of waiting? Gun down those ahead of me? Shoot

the guy servicing my car because he tries to stiff me on the bill?

The crime scene still has tape fluttering in the breeze. It isn’t really a crime scene. It’s more of a depraved scene, where the dead were replaced by a different dead. The digging equipment

has gone. The tents have been taken down. The grass has been

trampled flat. The circus that came to town has left. I stare out at the lake. I wonder how deep it goes, and how it was down there in the water for the divers. I go over the last two days, trying to filter everything until the answers are clear, but if there are any answers I keep missing them.

When I move away from the water, I don’t look back. I reach

the caretaker’s grave and I stand next to the turned-over dirt, and I listen to the wind and the early morning and I listen for a voice coming from beneath my feet. There is none. I drive to the church.

I leave my car running and walk up to the big doors and start

banging on them, breaking the promise I made to Father Julian

that I’d never return. There is no response, so I walk around the side and start banging on a much smaller door.

Father Julian yells at me to hang on. A few moments later the

door unlocks, then swings open. He is wearing a pair of faded

pyjamas and a robe. His hair is stuck up on one side.

‘Theo. What are you doing here? Do you know what time it

is?

‘You have to help me.’

‘Help you? I’ve done enough of that lately’

‘Please, this is important. Sidney Alderman, was it him?’

‘I can’t…’

I reach out and grab hold of his arm, and rest my other hand

on his shoulder. I grip him tightly and pull him forward so our faces are almost touching. ‘Was he the one?’

‘Theo …’

‘If he was, you don’t have to tell me. You wouldn’t be breaking the confessional seal,’ I say, and I can hear the desperation in my voice. ‘But if he isn’t, if he didn’t confess, you can tell me. God won’t care about that.’

‘What have you done, Theo? What have you done?’

‘Tell me.’

He looks into my eyes, because at this distance there is no

alternative. Slowly then he starts to shake his head.

‘Go home, Theo.’

“Not until you tell me.’

He reaches beneath my grip and pushes me in the chest.

I stumble back and don’t fall down, but I feel like I’ve fallen anyway.

‘Bruce buried those girls for somebody,’ I say. ‘Was it his

father?’

‘This has gone on long enough.’

‘Was it for you, Father?’ I ask, unsure where the question is

coming from. ‘Did you kill those girls? Was Bruce burying them for you? Sidney said to ask you about it. He said you knew a lot more than you were saying. How deeply are you involved? Did

you kill those girls? Or are you just happy to protect the man who did?’

‘Get out of here, Theo. Get the hell out of here or I’m calling the police. I mean it.’

He takes a step back and slams the door.

I stand in the same spot for half a minute, wondering if the

exchange really happened the way I recall it – whether Father Julian had Bruce bury those girls – and questioning what insanity has come over me to think such a thing.

I’m sure he watches me from somewhere inside the church

as I make my way back around to the car. I feel dizzy, and I feel sick, and my stomach feels hollow, as if I haven’t eaten in months.

I climb into my car, and I drive away from the graveyard, certain now that I’ve killed an innocent man.

chapter twenty-five

The city is white and cold and full of long shadows. The air is like ice. The heater is strong enough so only the edges of my

windscreen have frosted over, but not strong enough to stop the middle of it from fogging. There are circular smear marks from where I’ve wiped it with my hand. My drink seems to be keeping the cold at bay much more effectively than the heater.

Winter hasn’t arrived yet, at least not technically, but that

hasn’t stopped the grass becoming crisp with frost and cracking like glass underfoot. The shadows of the cement markers are

longer than they were a month ago when I fell into the lake.

You just never know what you’re going to get with this city —

one year the days don’t get cold until the middle of winter, another year you’ve got frosts in autumn. At the moment the air is deathly still. The trees are motionless, caught in a snapshot. Nothing out here is moving. The church looks uninviting, as if the desperately cold temperature inside has convinced even God to move out. But it’s not completely empty. Father Julian is in there. Somewhere.

I take another sip. My throat burns. I shiver.

The clock on my dashboard is out by an hour because I never

got around to changing it when daylight saving ended. It says

169

9 a.m., and I know that means I have to add an hour or perhaps subtract one – I can’t remember which. Not that it matters.

I watch the police car in the rear-view mirror as it rolls to a stop behind me, the gravel twisting and grating beneath the wheels.

Nothing happens for about thirty seconds as the occupants wait in the warmth. Then the doors open. The two men approach. I

roll down the window just enough to speak through. The winter

morning seizes on the moment and floods the car with such

savage cold air that every joint in my body starts to ache.

‘Morning, Tate,’ the taller of the men says, using just the right tone to suggest he’s ready to haul my arse down to the cinderblock hotel. His words form tiny pools of fog in the air.

“I thought it was afternoon.’

‘You can’t be here.’

‘My daughter is buried here. That gives me the right.’

“No it doesn’t.’ ‘This is public property.’

‘There’s a protection order against you, Tate. You know that.

You can’t come within one hundred metres of Father Julian.’

‘I’m not within a hundred metres of him.’

‘Yes you are.’

“I don’t see him.’

‘That’s because he’s inside.’

‘But it would’ve been illegal for me to go to check, don’t you think?’

‘What I think is that you’re doing your best to get arrested.’

‘Then you need better thoughts. Shit like that will only bring you down.’

‘Is that what I think it is?’ He’s looking down at my Styrofoam coffee cup that doesn’t have coffee in it.

‘Don’t know. It depends on what you’re thinking. You’re a

whole lot more negative than I gave you credit for.’

He looks over at his partner, then back down at me. ‘Jesus,

Tate, it’s a bit early to be drinking, isn’t it?’

‘It’s happy hour somewhere in the world.’

‘Then coming with us isn’t really going to set you back.’

They open the door for me and I step outside. My breath

forms clouds in the air. The gravel crunches beneath my feet, tiny pieces of frost snapping between them, and the trees that were ever so still while I was sitting down seem to lunge towards me as I walk. The officers escort me to the back of their car, and I have to reach out and grab hold of it to stop from falling over. Then they take the bourbon off me. Christ, what next? First I lose my family, now I lose my ability to drink?

The police car is warmer than my own, and the view somewhat

better since the windscreen isn’t iced over. The drive doesn’t include any conversation, and I pass the time by looking down at my feet and telling myself not to be sick, since the car seems to be swaying all over the place. At the station we ride up an elevator that seems to move way too fast and I have to grab a wall. Then the men march me past dozens of sets of curious eyes. I don’t

meet any of them; I just glance at their looks of disappointment before reaching an interrogation room.

They sit me down in front of a desk that in another life I used to sit on the other side of. They close the door and I stand back up, only to find that it’s locked. I walk around for a bit before deciding I might as well sit back down. I know the procedure.

I know they’re going to make me wait before sending somebody

in. I need to use the bathroom, and if they wait too long I have no reservations about pissing in the corner. Why should I? If I can kill people, I can do anything.

It takes forty minutes before Detective Inspector Landry

comes in. He’s carrying only one cup of coffee that I know isn’t for me, and a folder that he sits on the desk but keeps closed.

He looks like he hasn’t slept in about a week, and there are dark smudges beneath his eyes. He still smells of cigarette smoke and coffee. He looks stressed. He’s been a busy man with all the rest of the bullshit that’s been going on in the city while he’s been trying to figure out how those bodies got in the water. Other

murders, other cases.

He sits down and stares at me.

‘Explain this obsession to me once again?’ he asks.

‘It’s not an obsession.’

‘You done being clever?’

‘Am I free to leave?’

‘What do you think? You violated a protection order. You were

in an automobile, behind the wheel, while under the influence.’

‘I haven’t been given a breath test.’

‘You want to take one?’

‘What would be the point? I wasn’t driving.’

‘But I could argue that you drove there drunk. Or were about

to leave drunk. Your keys were in the ignition.’

‘You could argue that, and I could argue that you’re an

arsehole.’

‘Fuck it, Tate, why the hell don’t you try to help yourself

here? Huh? Why don’t you capitalise on the fact that right at this moment I’m the best friend you have in this city.’

And why’s that?’

‘Because you made the call and gave us the names of the other

two girls. That got us started.’

‘That was a month ago,’ I say. It was the same day I contacted Alicia North, the best friend of Rachel’s that David had told me about. Alicia North hadn’t heard of Father Julian, hadn’t heard of Bruce or Sidney Alderman, hadn’t heard of anything at all that could have helped me. It was also the same day I started cracking lots of seals on lots of bottles of alcohol in order to push the visuals I was having of a lifeless Sidney Alderman into the back of my mind.

‘Yeah, it was a month ago, but I’m a giving guy and right now

I’m giving you some goodwill. See, the way we’ve been seeing it, Sidney Alderman did a runner the same day you told me you had

the names of the girls and a day before somebody rang the horiine with the anonymous information. Since then there haven’t been

any more missing girls.’

‘So I’m in your good books and Alderman is in your bad

books. Fine. You going to let me go?’

‘The problem,’ he says, and he makes a face when he sips at his coffee, ‘is Father Julian. Somehow he fits into all of this, and that’s a problem. For us, for him and for you. If you thought the case was over, you’d be at home right now. You wouldn’t be following Julian. And if you believed Alderman was guilty, you’d be out

there looking for him.’

“Now you’re the one who seems obsessed.’

‘Strange that Alderman didn’t wait to see his son buried.

He didn’t take his car. He didn’t pack any clothes. That adds up badly, Tate, and I keep coming to the conclusion that you know something about that. How many times have we pulled you in

here now?’

‘If you’ve got a point, just make it.’

‘How about you take this chance to explain things to me, and

maybe I can start to figure out what in the hell is happening to you. Jesus, you’re more drunk each time we drag you in. This is the third time since the protection order was issued a week ago.

Anybody else and they’d be kept in custody. They’d be facing

time. There ain’t going to be any favours if we bring you in for a fourth. Come on, man, you know sending an ex-cop into prison

isn’t going to be pretty’

‘Can I go now?’

‘No. Tell me about Father Julian.’

‘What about him?’

‘You’re practically camping outside his church in your car most nights. That booze is fucking up your brain because you can’t

figure out what a protection order means. He says you’re stalking him, and that’s exactly what you’re doing.’ He takes another sip of coffee, puts it down and leans forward. ‘Unless I’m missing something here, it looks like you want to end up in jail. Is that it?’

I shrug as if I don’t care, but the truth is I don’t want to end up in jail. If I wanted that, I’d tell him all about Sidney Alderman and where they could find him.

‘So what is it about him that makes you want to sit outside his church watching?’ he asks.

I try to maintain eye contact with him but say nothing.

‘Jesus, Tate, give yourself a chance. We’re through playing

games. Next time we bring you in here, you’re staying. You get my point?’

‘You’ve said it twice. I got it each time.’

‘Yet here you are.’

‘Look, I’ve got nothing else to say’

‘Well, the opposite goes for Father Julian. He has plenty to say about you.’

“I doubt that.’

‘Why’s that? You think anything you’ve said to him is covered

by priest-parishioner confidentiality? You’re right – to a point.

He says anything you’ve told him he can’t share. But what he can share is his concern. He said four weeks ago you went in there and asked him to help you find Bruce Alderman. We all know where

that led, right? Next thing we know Bruce Alderman shows up in your office dead.’

‘Look, Landry, he didn’t show up dead, okay? It’s not like he

fucking shot himself before walking into my office.’

‘The following day you go see Father Julian again, this time

asking for help in finding Sidney Alderman. It’s the same day you call me telling me you know who the missing girls are. Father

Julian said that if he knew where Sidney was, he’d tell him to stay clear of you. Why do you think he’d say that?’

I look down at my thumb and the deep scarring from the bite

that Sidney Alderman took. Sometimes it still hurts.

‘You think Father Julian is guilty of something?’ he adds.

‘What would he be guilty of?’ I ask.

“I don’t know. You tell me. You think he killed those girls?’

‘This is bullshit,’ I say.

‘He knows something about you, something he wouldn’t tell

me. But I’m figuring it out,’ he says, and he runs his hand across the cover of the folder he brought into the room with him. The folder is thick, and the pages between its covers could be blank for all I know, though Landry wants me to believe they’re full of circumstantial facts that any moment are going to line up in the right order for him to arrest me for something.

I say nothing.

Landry fills in the silence. ‘See, it’s just a matter of connecting the dots. Yours are easy, because it’s a simple timeline. The last two years, Tate, you’ve had a lot happen. The accident with your family I sympathise with you – nobody should lose what you’ve lost.’

I still say nothing. I don’t want to help Landry get to wherever he is leading.

‘What do you think ever happened to Quentin James?’ he

asks.

“I don’t know’

‘You seem calm about that, Tate. Me, I’d be angry as hell. I

don’t think I’d have resigned myself to the fact that he got away.

I’d be jumping up and down and phoning the police and phoning

the media and I’d be out there looking for him. I’d be annoying the hell out of everyone – asking questions, putting pressure on anybody I could to make finding Quentin James a priority. But

not you.’

‘Maybe he’ll show up one day and justice can be served.’

‘If it hasn’t been already. It’s hard to go missing for that long, especially in this country. Then a month ago things change again.

People die. They go missing. And what happens? You start

drinking. You start showing up at the church drunk. You harass Father Julian. You hound him with questions. A week ago he

takes a protection order against you and you just ignore it. Want to know what I think?’

“Not unless you’re going to charge me with something.

Otherwise, I’m leaving.’

I stand up. The interrogation room sways a little. I reach down and grab the desk.

‘Sit back down, Tate, before you pass out.’

‘Charge me or I’m getting a lawyer.’

‘You violated a protection order. That means we can charge

you.’

‘Then do it. You think I care?’

‘You know, I don’t really think you do. And that’s the problem.’

Landry gets up. He picks up the folder and his coffee, and he

walks to the door. He juggles them so he can manage the handle.

‘I can see I’m wasting my time here. But let me warn you, don’t go back to the church. You go anywhere near Father Julian and

I’m going to have you arrested. There’s going to be no more of this bullshit, right? No more of us feeling bad at the shit you’ve had to go through; no more of the people here feeling sorry for you and searching inside themselves to still care. You’re falling apart, and any loyalty you built up here is rapidly dissipating. You want to stay out of jail? Then you need to take a good long hard look at yourself and figure out what’s wrong. You get me?’

I get him.

‘And for Christ’s sake, Tate, go home and take a shower. You

smell like a brewery.’

chapter twenty-six

I sit back down and wait for a few minutes, thinking about what he’s said, trying to decide whether the police could help me if I told them the truth, or whether they would crucify me. When

I get up, I have to hold onto the desk again while I get my balance.

In that time I come to the conclusion that Landry doesn’t have any idea what he’s talking about – none of these people do – and that they should just leave me the hell alone.

From every cubicle and every corner of the fourth floor

somebody is staring at me. I make my way to the elevator. Two

years ago I was part of this atmosphere. I was one of the team, doing what I could to try to repair the broken bits of this city, to fight back the tides of surging violence in what was, and still is, a losing battle. Then things changed. The world changed. I handed in my resignation because I knew the department was

going to ask for it. I didn’t want to stay and didn’t know what I was going to do once I left. The day I walked out of here, I had people coming up to me and patting me on the shoulder or shaking my hand and telling me that whatever happened to the missing Quentin James was something he deserved. Nobody came right out and said they knew I had killed him, because nobody

knew and, more importantly, they didn’t want to know. They all had suspicions, and they were all on my side, but if any proof had come along they’d have locked me up without remorse.

Now these same people stare at me. Nobody approaches. They

look me up and down; they study my wrinkled clothes and my

unshaven face, and they wonder what shitty thing could happen

in their lives to turn them into me. They’re wondering just how far away I am from drinking myself to death; whether the booze will get me or whether I’ll end up sucking back the barrel of a shotgun. Hell, we’re all wondering the same damn thing. I feel like shouting out to them that I don’t fucking care any more, and that I don’t want their pity.

I reach the elevator and before the doors can close Landry slips through. He has a packet of cigarettes in his hand.

The elevator starts its descent. I can feel it in my stomach, as if we’re falling at a hundred kilometres an hour. I hold onto the wall. Whatever conversation Landry is planning has to be short.

‘I know you killed them,’ he says. ‘Alderman and James.’

He turns towards me and lightly pushes me against the back

of the elevator. He holds his palm on my chest and keeps his arm straight, as if holding back a bad smell.

‘This Quentin James arsehole, I don’t give a fuck that you

killed him. Hell, it’s one thing we have in common, because

sometimes, sometimes, I think I’m capable of doing the same

thing. But that’s the difference, right? I haven’t had to cross the line because I haven’t lost what you’ve lost. And who knows?

Maybe any one of us here would’ve done the same thing. This

job, Tate, it’s a fucking mission – but now you’re on the wrong side of it. See, we could forgive you with Quentin James. But not any more. Whatever you’re doing now, it’s my job to find out.

It’s not because I hate you, you know that. It’s because it’s part of the mission. You would have understood that once. You might be willing to let your world fall apart, but think of your wife. Are you really that prepared to let her waste away …’

I push him away and take a swing at him. He ducks, pushes my

arm in the direction it’s going, and slams me into the adjoining mirrored wall. My face presses up against it and the view isn’t good. There are red cotton-thin lines running through my eyes, tying my pain to the surface for all to see. My breath forms a misty patch on the mirror.

‘You done?’ he asks.

‘I’m done.’

The doors open and he lets me go. I walk out and he follows.

He taps his cigarettes in his hands and walks off in a different direction. I do my best to hold a straight line, but it’s impossible.

I use the ground-floor toilet before heading outside.

The cold air makes me feel sick, just as almost everything

seems to now. The chill stirs up fragments of the conversations with Landry. The bourbon floating in my system doesn’t keep any of them at bay. I hail a taxi, and when I’m home I hover in the hallway in case I have to dash into the toilet to throw up. Then I stagger down to my bed. I crash on top of it and fall asleep for the rest of the morning and into the middle of the afternoon.