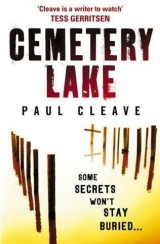

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter twenty-two

There is an abyss. Those it waits for can stand on the precipice, some live there, and then there are those who sink into the depths as if attached to cinderblocks. I’m not sure where I stand, and that might be one of the problems with the abyss – you never

really know if you can keep dropping lower. That’s what the last two years have been like. I slid into the abyss, and what I saw down there frightened me; since then, I’ve been doing what

I can to pull myself away. Perhaps, though, all I’ve been doing is staying at the same depth, just waiting for one more moment to sink me lower.

I think that moment is here. I don’t know. I hope the fact I’m indulging in some self-evaluation means I’m aware of the slide, just as an insane man can’t be insane if he is wondering if he is.

A man who thinks he has sunk as far as he can perhaps hasn’t

sunk that far at all. The problem is, when you’re sinking and not looking for a life preserver to pull you back, then perhaps you really are gone.

I try making another call, but Sidney doesn’t answer. His phone is switched on, because it goes to voicemail after five rings. He’s probably sitting there staring at it. He’s got my dead daughter in the back of his car and that means he’s going to ignore my

calls. He’s got his own dead son whom he has to start making

arrangements for lying on a slab of steel in a cold morgue with a sheet draped over him. He has to start picking out coffins and flowers and headstone engravers. He has to pick out a suit for his son, and a funeral home, and he has to let people know so they can show up. He’s got a lot on his mind. But he has to figure out first what he’s going to do with Emily. And he’s worrying about what I’m going to do to him.

I close my eyes. I question what I’m doing, but not enough to

stop doing it. I send him a text.

I want my daughter back and you’re going to give, her to me.

We’re going to make a trade. Trust me, it’s a trade you’ll be willing to make.

I’m sitting in the digger underneath one of the bluest skies this summer. I’m parked back by the shed. It feels like I’m melting out here. It’s taken me the best part of two hours to do what I figure would have been a twenty-or thirty-minute job for one of the Alderman duo. Nobody came over to investigate the sound.

Cemeteries don’t get a lot of foot traffic in the middle of the week, and I’ve had this area all to myself.

The phone starts to ring. I flip it open.

‘Fuck you,’ he says. ‘You murdered my boy, and you think you

have something to trade?’ His words are slurred, and I realise whatever bar he dragged himself out of to take my daughter away he has crawled back in to.

“I didn’t kill your son.’

‘He’s dead, ain’t he?’

‘Bring back my daughter and we’ll talk about it.’

‘What?’

‘You heard me. I want to make a trade.’

‘Trade? You have nothing that I want.’

‘That’s what I thought at first. Until I started playing your

game. The digger wasn’t that hard to use. I got the hang of it in the end.’

‘Where are you?’ he asks.

‘I’m where you were ten years ago,’ I say, and I hang up.

A few seconds later the phone rings again. I switch it off

There’s a tap outside the shed and I’m thirsty, but I don’t want my lips to touch anything that Sidney Alderman’s lips might have touched. I climb down from the digger and step into the shade.

I start going through the tools. Gardening equipment, mostly,

but some carpentry stuff as well. Could be that twenty years ago and in a different life, Alderman had a hobby. Maybe he and

his son would hang out in the shed and make wooden stools or

birdhouses, and they’d shoot the breeze with small talk about

angles and mitre cuts and joints. There are power tools for every occasion too. I ignore them all and pick up a shovel.

I carry the shovel back to the grave rather than taking the

digger. I rest beneath a tree that shelters me from the sun. I try not to think about the last twenty-four hours that have led me here, then I realise it’s actually the last two years that have done it. I wonder if the man I was back then would ever have thought of pulling the sort of crap he’s able to do now. I hope not, then I figure that if I was going to hope for anything it’d be that the last two years never happened.

That immediately leads me to start thinking about Quentin

James. I have had two lives – the one before meeting James,

and the one after – and I have been two separate people. I guess in a way that makes us similar. There was Sober Quentin and

Drunk Quentin. There was probably a third Quentin too. One

who recognised the change, but one who was kept quiet with

beer and sports TV and mortgage payments. There is a third Tate – one who can’t say no to whatever the hell it is that I’m doing now. I felt so many things when Quentin told me he was sorry,

but pity wasn’t one of them. I don’t feel it now either.

It takes Alderman thirty minutes. The sun is a little lower

but no less hot. The beaten-up SUV comes along the road, the

sun glinting off the windscreen, which is the only clean surface on the vehicle. The vehicle sways left and right as he struggles to control it.

I don’t move. He parks as close as he can get, and when the

door opens he steps out and pauses, looking around for what

I can only guess is me. He doesn’t see me. He has to pass through the section of trees where I’m sitting but still he doesn’t see me.

He approaches the grave slowly, swaying slightly as he walks,

as if the world is dropping away from beneath him with every

footstep. Me, I’d have been running. He reaches it and he stands at the edge and he looks down and he does nothing. Just looks

into the earth and sways, staring, just staring, until finally he climbs in.

I move towards him. The angle increases the closer I get,

allowing me first to see the opposite edge of the grave, then

Alderman’s head, and then the rest of him. He’s in there trying to pry up the edge of his wife’s coffin, but it’s difficult because all of his weight is on the lid. My shadow moves across the casket and he notices it. He looks up, having to twist his body to do it, which is a little awkward for him. He’s straddling the coffin like a horse, except he can’t get his legs over the sides. He’s looking up into the sun and has to hold a hand up to shade his eyes.

‘You fucker,’ he says.

‘Where is she?’

He gets to his feet, and has to reach out to steady himself

against the dark walls. I show him the shovel.

‘You think I’m afraid of you?’ he asks. ‘You think I haven’t

been waiting for something like this?’

I smack him in the side of the face with the shovel – not hard, but hard enough for him to fall back, his legs coming up and his head bouncing into the coffin.

‘Jesus,’ he says, touching his face. He leans to his side and spits out some blood, then wipes his hand across his mouth. ‘Fuck.’

‘Where did you put her?’

‘Fuck you,’ he says. ‘Is my wife in here? Is she, you piece of shit?’

‘She’s there, and unless you want to join her you’re going to

tell me where you put my daughter.’

‘Your daughter? How about you tell me where my son is?

Or have you forgotten? He’s down at the fucking morgue!’ The

words forced from his mouth are surrounded by booze and

spittle. ‘Yeah, he’s getting cut to pieces with fucking bolt cutters and blades, and you know what? You want to know the fucking

punch line? You put him there!’

There’s no point in arguing. No point in telling him over

and over that I did not shoot his son. Casey Horwell has already convinced him otherwise.

‘My daughter. Where is she?’

‘You shot my boy.’

‘Tell me!’

‘You’ll never find her.’

‘Goddamn you,’ I say, and raise the shovel as if I’m about to

hit him again. He flinches away, and I take a step back. ‘Goddamn it,’ I repeat, and I throw the shovel at him. I throw it hard. The shovel head hits him in the shoulder and bounces onto the coffin lid. Alderman falls back and braces himself against the wall. He starts massaging the impact point on his body.

I curl my hands into fists; I’m shaking, and I’m not really sure exactly where this anger is going to take me. The bottom of the abyss is waiting.

Alderman picks up the shovel and uses it to get to his feet.

He reaches for the edge of the grave. I figure he must be drunk, because he puts his hands over the edge as if he thinks he can pull himself out and not have anybody try to stop him. I squeeze my foot down on his fingers. He pulls them back, raking the skin off the back of his hand. He looks up at me as if he’s the victim here, as if he’s done nothing wrong. There is a patch of blood starting to spread on the shoulder of his shirt and now on his hand.

‘The girls, what happened?’

‘What girls?’

‘What girls do you think I’m talking about?’

He shrugs, but he knows. “I had nothing to do with them.

And nor did Bruce.’

‘He buried them. He admitted to that. Did he kill them?’

‘Fuck you.’

‘Or did you kill them?’ I ask.

‘This is bullshit. All you’ve done is kill my son and you don’t even know why’

‘How about you explain it to me?’

‘You’re asking the wrong man.’

‘Who should I be asking?’

‘Who the hell do you think? Your pal Father Julian. Go ask

him all about it.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘Fuck you. I’m not saying another word until you let me out

of here.’

I back away from the grave.

‘Where the fuck are you going?’ Alderman calls out.

I don’t answer him. I walk over to his SUV It’s dusty and

there are several rusting stone chips across the front of it. The driver’s door is open and there is a ‘ding, ding’ sound coming from the dashboard – his keys are still in it. I pop open the back door. My daughter is sprawled out in the back beneath a dark

blue tarp, her hair all matted and limp, her favourite dress in better condition than her body. Her little body has been ravaged by decomposition. I lean against the SUV and I keep my eyes

downcast, fighting the nausea, not wanting to look at her face because much of it has gone. It has rotted away, leaving a mask of such horror that all I want to do is scream. She should be in school right now. Should be two years older. Should be looking forward to going home and getting her homework out of the way

so she can spend time having tea-parties with teddy bears. Jesus, this world is so fucked up that it’s starting to make me think what Bruce Alderman did last night isn’t such a bad option.

I close the door. I walk back to the grave. Alderman is still

making his way out of it. He’s struggling because the dynamics are difficult for him. He’s drunk, his body can’t perform as well as a younger man’s could, his shoulder hurts and his fingers hurt, and he’s having difficulty getting up over the edge. He needs to be taller or stronger or younger or sober, or he needs a ladder. He looks up at me.

‘You son of a bitch,’ I say.

‘So I was wrong. So you did find her.’

‘It’s time you gave me some answers,’ I say, and I reach down

and grab a handful of his hair in one hand and the front of his shirt in the other. I pull him up hard, wanting it to hurt, and he grunts as his body is dragged over the edge of the grave.

‘Ah, fuck, slow down, damn it,’ he says, but I have no intention of slowing down.

“I didn’t kill your son,’ I say, and I keep pulling him upwards.

He braces both his hands over my hands to relieve the pain

that must be flooding through the top of his head. I can hear

scalp and hair beginning to tear.

When he’s out far enough, he gets his knees on the ground

and stops trying to hold onto my arms. Instead he twists his head, pulls down on my hand and clamps his teeth over my thumb.

‘Shit,’ I say, and I pull back my hand, but it’s no good. He’s biting hard, trying to sever the thumb.

I can’t crash my knee into his chin because it’ll push his teeth all the way through. Instead I let go of him and hit him. His head moves, making his teeth rip at my thumb like a great white shark sawing through its prey by shaking its head. So I push forward.

We both stumble, and a moment later we’re falling through the

air.

And back into the grave.

chapter twenty-three

Mostly I land on Sidney Alderman. My elbow crashes into the

coffin and my thumb is jarred from his mouth. My knee hits

the wall, but the rest of me lands against the old man so the impact is cushioned. Alderman isn’t so lucky. He doesn’t have anybody to land on. Just his wife, except that her years of offering any support are over. So he lands hard up against the wood with the shovel beneath him – harder, I imagine, than if he were falling in there by himself. Because I’m falling with him, there’s my weight and there’s momentum and the laws of physics, and they all add up very badly for Sidney Alderman. His head bounces into the

edge of the coffin.

I push myself up, bracing my hands against the dirt walls and

the coffin. Blood is pouring from my thumb. The edges of the

bite have peeled upwards, revealing bright pink flesh. I reach into my pocket for my handkerchief and wrap it tightly around the

wound. It doesn’t hurt, but I figure in about twenty seconds it’s going to be killing me. I get to my knees and shake Alderman

a little. There is no response, so I shake him harder. When he doesn’t stir, I take the next step and search for what I’m beginning to fear, putting my fingers against his neck. Blood starts to leak onto the coffin. The lid is curved slightly, so the blood doesn’t pool; it runs down the sides and gets caught in a thin cosmetic groove running around the edge of the lid. Drop after drop and it starts building up; it climbs up over the groove and soaks into the dirt.

There is no pulse.

I start to roll Alderman over, but stop halfway when I see the damage. The tip of the shovel is buried into his neck, its angle making it point towards his brain. His head sags as I move him, and the handle of the shovel rotates. His eyes are open but they’re not seeing a thing. I let him go, and he slumps back against the coffin. My hands are covered in his blood. I stare at them for a few seconds, then wipe them on the walls of the grave, then stare at them some more, before shifting my body as far away as I can from Alderman, which isn’t far. I wipe my hands across the wet earth once more and clean them off on my shirt. All the time

I keep staring at Alderman as if he’s going to sit up and tell me not to worry, that these things happen, that it could’ve happened to anybody.

Jesus.

I climb out of the grave. It’s a lot easier for me than it was for Alderman because I’m working with a whole different set of dynamics. I lie on the lawn, staring up at the sky that is just as blue as it was when I was sitting in the digger, digging up the grave.

Jesus.

I get up and start staring at Sidney Alderman from different

angles that don’t improve the situation. I try thinking about

Emily, looking over at the SUV which is hidden by the trees,

knowing she’s in the back, hoping her presence will make things seem better than they are. Hoping to justify Alderman’s death by thinking he deserved it. I try this, but it doesn’t work. It should do. But it doesn’t. He deserved the chance to tell me everything he knew about the dead girls, and those dead girls deserved that too. I think about Casey Horwell and I wonder how she’d react if I called her and told her where her story had led. I figure she’d be thrilled – it’d give her the airtime she is desperate to get.

I walk over to the trees so I can see both the grave and the

SUV I look from one to the other. Is there a next step? I figure there is. There always is. I have, in fact, two first steps to choose from – the problem is each one heads in a different direction.

The first one requires me to reach into my pocket for my

cellphone and call the police. Only I don’t. They’ll say I wanted this to happen. They’ll say Alderman pushed me too far, and that I reacted. Only they’ll say I had time to calm down, because there were several hours in between Alderman taking Emily out of the ground and me putting him in it. Hours in which I dug up his

wife’s grave, spoke to the priest and continued the investigation.

So they’ll say I didn’t snap. They’ll say it had to be premeditated, because I had plenty of opportunities to go to the police but I didn’t. They’ll say I knew what was happening, that I looked into the abyss and dived right in.

I go with the other direction.

I climb back into the grave and roll Sidney Alderman over.

His blood is now pooling on each side of the coffin. I tug at the shovel, but at first it doesn’t move. It’s caught on something inside his body. I shift it from side to side, loosening it like removing a tooth, and it comes away with the squelching sound of pulling

your foot out of mud. I toss it out onto the grass and climb back out.

I walk to the other side of the trees and scan the graveyard.

There isn’t a soul in sight. I walk back and start to scoop dirt on top of Alderman. It hits him heavily: some pieces stay where they hit, others roll down his side and into the blood. The sound can’t be mistaken for anything other than dirt against flesh. I drop the shovel. There are black crumbs of soil stuck on the end of it, glued there by Sidney Alderman’s blood. I make my way back to the

shed and return with the digger. I can only take the road so far before I have to drive over and around other graves and around trees to reach the plot, and when I get there it doesn’t take as long to fill the grave as it took to empty it. When I’m done I drive the digger back and I stand in the shed, trying to keep my feet under me as the world sways. Another Tate has just been added

to my collection of personalities. Each one more fucked up than the other. Leading me where?

A tightness spreads across my chest, and suddenly the shed

seems way too small, the walls cramping in, the ceiling lowering down. I get outside only to find that the whole world doesn’t

seem big enough any more.

The clouds are back, the sun completely gone now. Dusk is

here, and it’s a little hard to make out the scenery. I find the SUV

and drive to my daughter’s grave. There I sit until a few nearby mourners leave the area. Then I carry her gently, scared she’ll fall apart, scared that I’m going to fall apart. I rest her on the ground, then climb six feet closer to the Hell that I’ve proven again I’m destined for. I reach out and scoop her up, then lay her down. She doesn’t look like Emily. She may be wearing the same dress, have the same hair, but everything else is different. It’s different in a way I don’t want to think about. I tuck her hair away from what face she has left and stroke it behind what ears she has left. I close the lid, not wanting to spend any more time with her, but at the same time I want to spend all night here, holding her hand.

I use the same shovel that killed Sidney Alderman to bury her.

It seems right I do it this way, and I relish the pain that courses from my thumb and up through my entire arm. It takes me an

hour, and when I’m done my shirt is covered in dirt and is damp all over and the day is dark and the makeshift bandage on my

thumb even darker. I throw the shovel in the back of the SUV

The vehicle is covered in my fingerprints. My own car is still here.

I’m a murderer, and if I’m not careful the world is soon about to know.

I drive back to the shed. I find some turpentine and soak some rags in it, then I go around wiping down every surface I’ve come into contact with. I drive to Alderman’s house and park up the driveway and I do the same thing there. I wipe down the SUV

and I carry the shovel back to my own car. When I leave, nobody follows me. Nobody seems to care.

The nursing staff at the home don’t appear thrilled to see me.

Carol Hamilton has gone for the day, and nobody else asks me

what in the hell I was on about this morning. Nobody asks why

I look like shit, my clothes messed up, my skin black with dirt, why I have a filthy handkerchief on my thumb. I spend an hour

with my wife, and now more than ever I need something from

her – a squeeze from her hand, or her eyes to focus on me and not past me – but she can offer me none of this. I don’t fill her in on anything that’s happened. I stare out the same window she stares out, and I see the same things, and this is the closest I have felt to her in two years. Part of me envies her world.

When I get home I break the shovel into half a dozen pieces.

I wipe each of them down, but I know I’ll need to do more than that – will have to dispose of them where they’ll never be found.

I climb into the shower then, and watch the dirt and blood wash away, though I still feel covered in it. I remove the handkerchief from my thumb and rinse the wound, which continues to bleed

weakly. It needs stitches but I’m not going to get them. I bandage it and make some dinner, but I can’t eat. I turn on the TV but can’t understand what the news anchors are even talking about. I grab a beer and sit out on the deck and stare at a piece of concrete we left exposed five years ago when we built the deck. The cement was wet and we carved our names into it so they could never be washed away. Daxter comes out and jumps up on my lap but

only stays a few seconds before jumping back down. I stare at

the names in the cement as I finish my beer, and then I stare at the ceiling of my bedroom while looking for sleep. I think of Quentin James and the Alderman family and the four dead girls I’ve never met. I have robbed their families of any closure, because the man who could help me is dead. Any hopes they had for answers

I took down into the abyss with me.