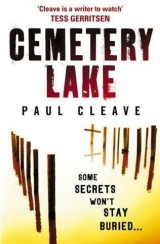

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter forty

I pin the photocopies of the newspaper articles up on the wall in my office and stare at the spot where my computer used to be until knocking at the front door breaks me out of the fugue. I think about ignoring it but it just keeps going. I head into the hallway and swing the door open. Carl Schroder is there holding two

pizza boxes in his arms. Suddenly he really is my best friend.

‘Thought you might do with some food,’ he says.

“I’m in the middle of cooking something.’

“I looked in that fridge of yours, Tate. What in the hell could you possibly be cooking?’ He braces the pizzas in one hand, a

bottle of Coke under his arm. He reaches into his pocket and

pulls out my keys. ‘Might make it easier for you getting in and out.

Saves breaking more windows.’

‘Seriously, Carl, this isn’t a good time for me,’ I say, taking my keys off him.

‘Spare me the bullshit. This place hasn’t had any food in it for a long time. Except for this kind. You’ve got enough pizza boxes stacked in your kitchen to build a fort.’

My stomach starts to growl and my mouth waters.

‘I was going to bring beer,’ he says, reaching under his arm and grabbing the Coke, ‘but something told me that was a bad idea.’

‘You’re a real funny guy’

We move through to the dining room. I grab some plates and

a couple of glasses. The pizza has a range of different types of meat on it, so between that and the Coke I reckon I’ll get the nutritional value I need for the day.

‘So why are you here?’

‘Look, Tate, Landry can be a real arsehole, but that doesn’t

mean he doesn’t have a point.’

‘Which is?’

‘The fact you’ve become a real mess.’

“I’m in the process of changing that.’

He looks around the room, absorbing the comment. “I guess

you are.’

‘That’s what life-changing moments will do to you.’

‘And what was that?’ he asks.

‘What do you think?’

‘The accident,’ he says, and he’s right – it was the accident more than it was being taken into the woods, or being framed for murder.

‘It’s kind of ironic,’ he adds.

I know what he’s getting it. He’s saying that if it hadn’t been for me driving through that intersection and hitting that car, I would now be in jail. I’d have been arrested for murder. He’s

saying that picking up the bottle and getting hammered was the only thing that kept the frame job on me from being complete. It all comes back to that word luck.

‘Did you really think I did it?’

‘Sure we did. Until the weapon showed up. That threw a

spanner in the works. Or a hammer, I guess, in this case. It messed everything up. So you were lucky’

“I shouldn’t have needed to be lucky. I didn’t kill the guy and that should have been enough.’

‘Come on, you know sometimes that isn’t enough.’

‘So why are you here, other than to make sure I’m eating

okay?’

‘How long’s it been since we hung out, Tate?’

‘Probably around the same time you stopped calling me. Hell,

it was the same time everybody stopped. If I remember correctly, it was around when Emily died.’

‘That had nothing to do with it.’

‘Then what was it?’

‘It was Quentin James. Nobody believes he ran. We all know

you killed him. But without a body, without any proof…’

“I didn’t kill him.’

‘Hey I’d have killed him. Any one of us would have – and

that’s why none of us looked real hard into finding him. It just sucked that it had to be you. And none of us wanted to hear you say it. What would have happened if over a few beers one night you told me what you’d done? What then? No, none of us could

call you, Tate. It was the only way. It was safer. And not just for you, for us.’

I don’t answer him. I’m not sure if he’s made a valid point

or whether he’s just made up an excuse that sounds believable. I guess if I were in his situation I’d have done the same thing.

We sit in silence for a few minutes, eating our pizza and getting through our Cokes. The Coke tastes different without bourbon

added to it.

‘Tell me something,’ I say, finishing one slice and getting ready to start another. ‘Bruce Alderman. Did you ever look at him for the murders?’

‘We looked at everybody’

‘Yeah, but how much did you look at him?’

‘Not as much as his Father.’

‘Which father?’ I ask.

If you’re trying to get at something, Tate, just spell it out.’

“I didn’t mean his priest.’

He sets down his pizza. ‘Who told you?’

“That Bruce and Sidney weren’t related? I’ve known from the

beginning. Do you know who the real father is?’

He picks up his slice and starts back in on it. ‘Tracey told you, that’s what I think. Probably recently too. Maybe today’

‘How’d you figure it out?’ I ask.

‘Probably the same way you did. You want to share first?’

‘Come on, Carl. You wouldn’t have come around unless you

had something for me.’

And you need to stop reading things into situations that aren’t there. I don’t have anything for you. I came around to check in on you.’

“I appreciate that,’ I say, ‘but come on, just give me that one thing. You know we fucked up two years ago. You know we could have stopped this, and three more girls would still be alive for it. I can’t let it go.’

He sits his pizza back down. “I’m surprised it took you this long to play that card,’ he says.

I don’t answer. I just wait him out and he carries on.

‘Like I said, we were looking at everybody, right? A case this big, all those girls – we’re gonna run all the DNA we can get hold of. Absolutely we’re gonna do that.’

And Alderman agreed to that?’

‘No, he didn’t agree. He didn’t even know. He came down to

identify his son’s body. When he took a swing at you, he hit the wall, right? That gave us his blood. We threw it into the database we were building.’

And?’

‘And the results are still out on DNA. Come on, Tate, this

shit still takes a couple of months to get back to us. Nothing has changed there. But blood tests proved the two Aldermans weren’t biologically related.’

‘Why’d you test?’

‘Like I said, all that stuff just gets done, right?’

‘What about Father Julian? You checking to see if his DNA

shows up anywhere it shouldn’t?’

“how did I know you were going to ask that?’

‘Well?’

‘You’ve had plenty of opportunities to tell us about Father

Julian, Tate. You kept refusing. But, like I say, we’re still waiting for DNA results.’

‘Father Julian was Bruce’s real father, wasn’t he?’

‘What makes you say that?’

I think about what Father Julian said about Bruce being like a son to him. A hunch.’

‘Don’t know. It’s quicker to disprove parenting through blood

comparisons, which we’ve done. But it’s going to take longer to confirm. We’ll know soon.’

“How soon?’

‘We’ll know when we know. That’s just the way it is.’

I wish testing was as quick as it is on TV It’s not. It’s about eight weeks of sitting around waiting while the specimens are sent out, tested, re-tested and sent back.

‘You’re going to compare the DNA you’ve been collecting

against the samples found at crime scene in the church?’ I ask.

‘Gee, why didn’t we think of that? Christ, I didn’t realise the impact of you leaving the force.’

“Yeah, good one, Carl.’

Tou fucked up,’ Schroder says.

‘What?’

‘This whole thing. You fucked up. And it’s only a matter of time until we find Sidney Alderman.’

‘When you do, can you ask him about Father Julian? Maybe he

knows something.’

“Yeah, I’ll make sure I do that. He wrap his hands around a crystal ball. See if that’ll help the conversation. It sure has to be better than this.’ He swallows the last of his drink, then stands up.

I walk him to the door.

On the step he turns around and faces me. ‘You know his wife

died in an accident, right?’

He knows I do. I found the article online and printed off a copy It was pinned to my wall with all the others.

‘What of it?’

‘With everything that’s going on, some bright spark had the

idea that maybe there was something more to her death.’

‘You’re kidding,’ I say, suddenly worried about where this is

going.

“I knope. It’s bullshit, right? It’s a stupid idea. But the decision has come down from the top. One of those dot the i’s and cross the Ts that’s going to cost time and money and get no result. The upshot is we’re digging her up on Monday’

‘Don’t you need something more to be able to do that?’

‘The gun Bruce shot himself with. Do you know where he

got it?’

“I always wondered.’

‘It belonged to his father. I mean it belonged to Sidney

Alderman.’

‘And?’

‘And Alderman bought that gun years ago. He bought it the

same week his wife died. About two days before she suddenly

jumped out in front of a car by accident. Hell of a coincidence, don’t you think?’

‘You think he bought the gun to kill his wife and pushed her

in front of a car instead?’

“I’m not saying anything. But you remember what happened

last time we started digging up bodies? I’m telling you, Tate, it’s going to be a long week. And take some advice – get yourself

a good lawyer, man. These drink driving charges aren’t going to disappear, friends in the department or not. You’re going to be doing some time. Get yourself sorted, start jogging – you’ve put on what, three, four kilos in the last month? Get your life back on track. Do anything else but this case, man. I know we could have made a difference two years ago, but you have to let it go and let the rest of us take care of it.’

His cellphone starts to ring.

“Hang on, Tate.’ He talks quickly into it, then hangs up. ‘Jesus, I gotta go,’ he says, and rushes to his car.

All I can do is watch him as he speeds out of the street, and all I can think about is what they are going to find buried in the dirt when they exhume Sidney Alderman’s wife on Monday.

chapter forty-one

For the longest time I can’t move. My breathing becomes

shallow and I start to sweat. The house is cold and the air slightly damp because of the busted window in the lounge. There is a

restricting pain in my chest. On Monday they are going to find Sidney Alderman buried on top of the coffin of his wife. He’s

going to look like he died hard. There are going to be contusions and gashes and deep cuts. Realistically there shouldn’t be any evidence pointing directly at me, not that I can think of, but there might be something. Regardless of that, they’ll know I did it. It won’t be like Quentin James, where they knew I did it but didn’t try looking too hard to prove anything. This time they’ll make an effort because the man I killed was innocent.

I walk outside to the garage and find a piece of plywood and

some nails; of course, I have no hammer. I use a drill and some screws to hold the plywood over the busted window. The work helps to calm me, at least for a few minutes. When the last screw is buried, I start to go through my options, and the one that keeps coming up is that I ought to call Carl Schroder and tell him to come back here. We could sit down and he could listen to my sins.

I sit down at the table and eat some more pizza. I need to

start making the most of good food, since I won’t be seeing any for another ten years. On the other hand, Schroder was right.

I should be joining a gym. Or at least running. Doing something.

I reach down and grab a handful of stomach. A month ago I was

lean. Now I’m not. I reach up and find extra padding around my neck and jaw that shouldn’t be there either. I hope Schroder’s estimate of my added three or four kilos wasn’t conservative.

I finish off the pizza and drink the rest of the Coke. Daxter

comes wandering down the hall, probably hoping I kept him

some pizza. I give him his usual and he seems placated by it.

I head to bed and set my alarm clock. I slide it to the far end of the bedside table to kill the risk of my reaching out and slapping the snooze button while still in some dreamlike state.

I end up dreaming about my wife, about Emily, and in my

dream they are both alive. They talk to me, but what they say

makes little sense, because in the dream I seem to be burying

my family while they’re still alive. Rachel Tyler appears – she’s a younger version, one of the Rachel Tylers on display in the

hallway of her parents’ house. She accuses me of murder, and in this world of dreams as well as outside of it it’s exactly what I am.

When the alarm goes off it’s two o’clock in the morning and

it’s raining. Daxter is curled up next to me, the first time he has done that in two years. I wonder if this means something. My

house is cold and my mind is full of bad ideas. I get dressed and step out into the night.

chapter forty-two

I thrrow a shovel into the back of my dad’s car, and park outside my house. I look up and down the street, searching for a tail, then drive off in the direction of the cemetery, taking random lefts and rights to make sure no one is following. I need to get Alderman out of the ground before the others go digging for his wife.

At the cemetery everything looks different, as though I’m still in the dream. The night is about as dark and wet as it can get in this city. There is an occasional sliver of pale light that breaks through and reflects off the windscreen. It is completely still out here, and cold. I suspect if I tried digging deep into the ground to remove Sidney Alderman, it’d be like digging through quicksand.

I park out on the street two blocks away and walk back to the

cemetery. Naked branches that look like skeletal remains reach out overhead and lock fingers above me as I enter the grounds. I slow down and stay hidden in the shadows of several oak trees along the sides of the road in case there are any police around. There doesn’t seem to be anybody, but I go further into the grounds

before going back for the shovel, knowing I could only offer bad answers to questions about why I was carrying one.

Satisfied I’m alone, at least in the cemetery, I start to make my

way to the church. I stay in the trees, getting close enough finally to see a patrol car parked outside with a sole officer inside. He’s probably got the heater running to stay warm, and got a thermos of coffee as well. It’s standard protocol to protect a crime scene this early on. I bet he’s as bored as hell. I stay in the same position, low to the ground, the cold making my knees and fingers hurt, and I spend ten minutes just watching. The rain beats on my jacket loudly, but not as loudly as it beats against the car. Occasionally a light comes on in the car from what I think might be a cellphone opening and closing. The guy’s probably sending text messages

to his wife or girlfriend, or both. Probably complaining about what a waste of time it is out here.

I need to return to the car, grab the shovel and dig Alderman

up. But now that I’m this close to the church, suddenly I have another, even stronger need – I have to know what’s inside. I need to know if there are answers in there. And anyway, Alderman won’t mind waiting another half an hour for the feel of the

shovel.

I pass behind the trees and some graves, and circumnavigate

my way to the back of the church. I hide for another five minutes, just watching and waiting to see if there is anybody else around.

There isn’t. The rain stays heavy and I’m pretty sure it’s the reason the cop keeping an eye on the church is staying in his car and not patrolling around the perimeter every few minutes like he’s been instructed to do.

The church is darker and colder-looking than normal, as

though God has moved out and some malevolent presence has

moved in. There are no lights on inside. The man who devoted

his life to this place is lying on a slab in the morgue, maybe with his God, maybe alone.

I quickly make my way to the side door and I pause, waiting

for either Schroder or Landry to step out of the darkness, or

even Casey Horwell with her cameraman. Nobody does. There

is police tape hanging in the lifeless air between poles that have been weighted on the ground. Police tape has been sealed along the framework. I try to pull it away without damaging it.

Among the keys that Schroder brought back to me is the one

Bruce Alderman left me. I look at the key and I look at the lock, and even though they don’t look like they’re going to match up, I still try jamming them together. It’s useless. It could be for one of the other doors. I pull a lock-pick set from my pocket, hold a Maglite in my mouth, and go about working at the lock, nervous that the guy parked out front is going to pick this exact moment to come looking around. It turns out to be a simple enough

pin-and-tumbler mechanism made more complicated than it ought

to be by the cold and my nerves. It takes me almost ten minutes to make my way inside. The air is cold, the black void ahead of me unwelcoming, and when I close the door behind me all I have is my Maglite to keep whatever demons are in here at bay

Before taking a step, I remove my jacket and shoes to avoid

contaminating the scene with mud and water. I’ve entered the

church in the corridor: to the left is the chapel and to the right Father Julian’s office. There is a basin of what I assume is holy water standing waist high next to me. The torch cuts a small arc through the inky darkness but is swallowed up when I point it at the far wall of the chapel – I’m sure it’s all but impossible to see it from outside. I run my hand along the top of the front pew where I sat last time I was here talking to Father Julian. It was when I was looking for Bruce Alderman. The following day I came back

and we sat in his office and I was looking for Sidney Alderman.

I turn off the torch and stand in the darkness. There is something here, I’m sure of it. Something dark. Perhaps the church itself is angry. Bad things have happened here. Sins have been confessed – have sins also been committed? The bricks and the mortar and the stained glassed windows have every right to be angry. They’ve absorbed a lot of what’s been said and seen over the years, and now that the keeper of secrets has gone all that sorrow and pain is starting to seep out.

I turn the torch back on and start looking around the chapel,

not searching for anything in particular. The only eyes watching me are those of the icons pinned on or hanging from the walls, created in coloured glass and woven fabrics and tapestries. Jesus feeding the poor. Jesus turning water into wine. Jesus dying for our sins. Did Father Julian die for his sins? For mine?

There are a few evidence markers placed variously around the

floor. Whatever they indicated has been photographed, picked up and gone. There are no blood splatters. No muddy footprints.

The other night, did Father Julian’s killer make his way into the church using the same means? Did he come through the front

door, allowed entrance by the priest? Through a side door? Did he come at night, or had he been here all day?

Did they know each other?

I rest my jacket and shoes behind the first pew and head down

to Father Julian’s office. It’s a tangle of books and papers and clutter strewn around the room – not from any type of struggle, but as though he was trying to find something in a hurry. Or

perhaps the police were, and this is the aftermath of their search.

This is the kind of thing I miss most about being in the force: losing the opportunity to see the crime scene in its original form.

There are more evidence markers, yellow plastic discs with black numbers printed on them. Fingerprint powder, small plastic bags, plastic vials, cotton swabs. Somebody must be figuring the maid will take care of it all.

I roll Father Julian’s chair away from his desk and sit down

behind it, then splay my hands on the table. I can’t feel the grain of the wood because I’m wearing latex gloves, but the desk feels solid, cold, as though it could last a thousand years. A sudden memory of my family comes to me. I’m at the beach with Bridget and Emily. We’re building a sand castle; my daughter’s face is full of smiles and freckles, her blonde hair shoved out at sharp angles by the Elmo cap pulled down over her head. The edges of the

ocean are moving forward, the water reaching the moat we have

dug, the walls of the castle only minutes away from falling into the sea.

‘It’s okay, Daddy’ my daughter says, and she stops digging,

understanding the futile nature of what she is trying to save. ‘We can always come back next weekend. We got forever more days to build another one.’

I take my hands away from the desk, and the memory

disappears. I don’t try chasing it.

I open the desk drawers one at a time, but all of them are

empty I pull them out completely and check underneath them S– again, there’s nothing there. I put them back and start flicking through the books on Father Julian’s desk, hoping something

might fall out from between the pages. Nothing does. No doubt

somebody else has done this already. I search under the desk, but there’s nothing.

I make my way around the room, unsure of what I’m looking

for. I open Bibles and books, novels and how-to guides, flicking through them but finding nothing. It doesn’t look like Father

Julian was the one who made this mess. The Father Julian I

knew never would have allowed his office to get like this. There are holes in the plaster walls obviously formed by fists. There are other holes down lower, kick marks made by somebody becoming

increasingly frustrated. Draughts of cold air come through them.

The books pulled from the shelves have been torn down and

tossed on the ground, discarded into piles. Some of the pages

and covers have been ripped away. Did whoever did this find what he was looking for?

I step out of the office, and carry on through to the rectory.

The beam on my torch is getting weaker, and I have the feeling that if the torch goes out completely the demons surrounding me will get a firm hold. Jesus looks down, probably in judgement, maybe wondering what in the hell a guy like me is doing in a

place like this. Well, Jesus, I’m trying to make compensation. “I’m trying to repent. That’s what you want, right?

I stop the torch on the floor where the dead priest lay while

I stood outside two nights ago worrying about being caught.

I crouch down by the edge of the chalk outline that shows the

Position in which he was found. The carpet beneath the chalk

head is almost black with dried blood. I close my eyes and think about the series of photographs that Schroder and Landry showed ne. Father Julian was lying on his back, his head twisted to the side. Closer photos showed gashes in the back of his head from the impact of the hammer. I don’t know how many times he was

hit, but it was more than once. Perhaps the first blow killed him.

At the very least it would have dropped him to his knees. I figure he ended up dead face down, but was rolled onto his back. I try to imagine the thirty seconds before that. Did Julian know his killer was there – if so, why would he turn his back on him?

The tongue had to have been cut out after he was dead. It’s

not the kind of thing you can do to a man unless you’ve got

him bound, and even then it’d be a struggle. The photographs

didn’t show any evidence of that, nor of any defensive wounds on Julian’s hands. I look up and point the torch at the ceiling. There are lines of blood up there, cast off from the swinging hammer.

I stand up. Father Julian’s tongue wasn’t cut out to frame me: that’s why it wasn’t dumped in my house with the hammer. It was cut out not as a message but from anger. Father Julian wouldn’t tell his killer something he needed to know. That made him angry.

That’s why there are holes in the walls even in the lounge of the rectory. What was he looking for?

The entire death scene is horrible under the focused beam of

a halogen bulb: it looks yellowish, like a faded newspaper article.

Everything in here looks old too, like it all came out of a 1960s catalogue. My immediate thought is that it can’t be a fun lifestyle being a priest. Everything you own has to be old and outdated.

It’s a lifestyle that doesn’t rely on monetary possessions, but on scripture and love and peace. In Father Julian’s case, perhaps a little too much love if it turns out he is Bruce Alderman’s

father.

The rectory is as messy as the office. Papers and books

everywhere. Furniture has been tipped up, the sofa and cushions torn open. The bedroom isn’t any better. The mattress has been pulled from the bed and sliced up, every drawer pulled out

and tipped over, a clutter of clothes and toiletries spewed across the floor. In the bathroom the medicine cabinet is empty. So is the space beneath the sink. I head back into the bedroom. There are framed photographs on the drawers – some have been tipped down, some have cracked glass. I don’t recognise anyone in them except Father Julian and Bruce Alderman. Most of the others in the pictures are wearing cassocks.

I pull up the corner of the carpet in the bedroom then, and

it’s a case of like Father like son. There is an envelope beneath it. I wonder who came up with the idea first – Bruce or Father Julian – and then I make room for the possibility it was a genetic link.

The envelope is full of photographs, fifteen, maybe twenty of

them. Most are of babies; there are a few of young children and a couple in their teenage years. I recognise Bruce Alderman. The photos were taken when he wasn’t looking at the camera, as if he didn’t know the photographer was there. In most of the shots

he is isolated, alone. But these images are out of context. They don’t mean anything by themselves.

It’s hard to know how many children I’m looking at here; the

ages and faces seem to change to a point where I can’t tell if a six-month-old baby is the same six-year-old or sixteen-year-old.

There are sixteen photos in total, but not necessarily sixteen kids.

It’s obvious the age of the photographs changes by the quality and condition of the paper they’ve been printed on, and by the clothes the kids are wearing. Some pictures look thirty years old, some look like they may only be a few. It’s impossible to know whether Father Julian took them or was sent them. Other than

the photos of Bruce, all the others are taken closer up – indoor shots of Christmas presents being opened, of birthdays, happy

moments caught in time.

I pull the carpet up further, then start lifting it in other areas of the rectory before returning to the office and doing the same thing there. Nothing. These photographs, these children – is this the secret Father Julian died for?

I head back down the corridor. I’ve been here over an hour

and Alderman is still waiting for me. I pass Father Julian’s office.

When I was here a month ago he apologised for the mess. He’d

obviously been looking for something. I squeeze my eyes shut

and try to focus. Something here is falling into place. I can see the edges of it, forming, forming … and I think of the key that Bruce Alderman gave me. No numbers, no markings. Did this

key belong to Father Julian? Is that what he was looking for?

Suddenly the door I used to enter the church opens up, then

closes. The muffled sound of a voice drifts down the corridor

towards me, followed by high squawking radio chatter. I duck

down behind Father Julian’s desk and turn off my torch. There

is more radio chatter; I hear the word ‘backup’; and I know the officer parked outside has asked for it because for some reason he’s decided to do his job and walk around the building and he’s found the security tape over the door has been tampered with.

I move to the side of the desk so I can see into the corridor.

The beam of a torch is bouncing from the floor to the walls. It’s getting brighter. I pull back just as the officer reaches the office.

The light hits the wall behind the desk. It moves over it and then moves on. He takes a step into the room and then takes a step

back out of it. He carries on to the next room. I figure I have about two minutes to get the hell out of here.

I get out from under the desk and move to the door. My feet

are silent on the cold floor. I listen to the officer making his way further along the corridor. Then I look around the door frame.

He’s further down the corridor towards the rectory. He goes

around a corner, and as soon as he’s gone I start back towards the chapel for my clothes. I reach the end of the corridor. A second flashlight, this one moving around the pews, suddenly moves

across the room and hits my body. I look away before it can hit my face.

‘You! Hey, you! Stop!’

But I do the opposite. I turn and run towards the exit.