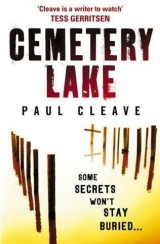

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter six

The elevator is chilly, as if it sucked in most of the cold air when the doors opened. Outside it’s only slightly warmer again. I think the sun could be melting the city into a pool of lava and I’d still feel this way after coming out of there.

On the way to my car I take the dead woman’s diamond ring

out of my pocket and begin to study it. There is an inscription on the inside, and I have to squint in the weak light of the car park to make it out. Rachel & David for ever. It reads like an adolescent inscription carved into a tree. The three stones are not diamonds, which could be why the ring was still by the woman’s hand and not sitting in some pawnshop gathering dust. They’re

glass, cloudy-looking glass that for some reason seems to make the poignancy of what happened to her that much more awful.

Somebody bought this for her; he couldn’t afford real diamonds, but she didn’t need real diamonds. Maybe they had a promise

that when things got better, when the money started flowing

from some plan he would one day hatch, he would buy for her

any stone she wanted. The ring didn’t come from her wedding

finger, it was from the other hand, but perhaps there were other promises too.

If Tracey spotted the ring, then pretty soon she’s going to

realise it’s gone. The question is what she’ll do about it. Call me?

Or call somebody else about me? I should never have put her in that position.

This time when I get back to my office I slip in behind my

computer and boot it up, studying the ring while I’m waiting.

If the ring had been expensive, or custom made, it might have

been easy to track down. I surf into a Missing Persons secured site accessible only to the police and social workers and a handful of private investigators. It only takes a few minutes to come up with a list of missing Rachels. I set the parameters of the search to go back two years, figuring she was dead after Henry Martins was buried.

I end up with two names, and one of them is from the same

week Henry Martins died. The description could easily match the Rachel I was looking at half an hour ago.

I print out Rachel Number One’s details. Nobody has seen

Rachel Tyler, the nineteen-year-old reported missing by her

parents, in two years. I don’t remember the case, and I guess

that’s because she was one of many girls believed to have run

away. The reality is people in this country go missing every single day. Sometimes they turn up: they’re broke and high and living in a single-room motel, having burned off all their cash in casinos betting on red instead of black. Sometimes they’re being pimped out, forced into prostitution to pay back money for gambling or drugs or as a form of self-abuse. Other times they’ve left their wife or husband for somebody with a bigger bank account or a bigger house or a younger body. Other times they don’t turn up at all.

The photograph of Rachel was taken at a moment of sourness,

either faked or real, and it sure beats seeing a happy and outgoing girl holding ice creams or diplomas or helping the sick and elderly.

She would be twenty-one now if somebody hadn’t killed her, then jammed her into a coffin.

I study the photograph. Her brown hair is darker than when

I saw it less than an hour ago; her blue eyes in the picture are bright and alive. I read through the file. The conclusion was that she ran away, that she fought with her parents or her boyfriend and couldn’t take it any more.

I look up the phonebook and find Rachel’s parents are still at the same address. I wonder if they’re still married and what kind of state they are in. I wonder how many nights they sit watching the door, waiting for her to stroll inside and tell them everything is going to be okay.

I slip the ring into a small plastic bag and drop it into my

pocket. Then I look again at the watch I took from the body

in the lake. I compare the time to my own. It’s out by only a

few minutes, but it could be the Tag that is accurate and my

one isn’t. Its owner must have died in the same six-month period we’re in now, between October and March, because the watch is

set for daylight saving time. The date is out by fourteen days.

I grab a pen and start doing the addition. Every month an

analogue watch goes to thirty-one days, regardless of what month it is, and the user has to adjust it manually in the other five months when there are fewer. I work out that those five months would

add up to seven days a year that the watch would be out by if it wasn’t adjusted. That means this watch hasn’t been touched in

two years. So. It is now nearing the end of February. The guy

who owned this watch was put in the ground sometime after the

beginning of December and before the end of February two years ago.

I pick up the file with Henry Martins’ details on it. He died on the ninth of January. Could be his.

I grab the phone. It takes half a minute for Detective Schroder to answer it.

‘Come on, Tate, you know I can’t answer any questions,’ he

says when he hears my voice. ‘This has nothing to do with you.

And soon it won’t have anything to do with me either. I’ve got too much on my plate to chase after this one too.’

‘You’re working the Carver case?’

‘Trying to. Unless I retire. Which I might.’

‘One question. The body that floated up without the legs. Is

that the oldest one?’

“I don’t know. Maybe. The ME said it’s hard to tell. Looks

like two of them went into the water fairly close to each other.

Why?’

‘Can you find out?’

“I can find out.’

‘And let me know?’

‘No. Goodbye, Tate,’ he says, and hangs up.

I look at the watch. It’s been on the wrist of a dead guy for two years, but not necessarily in the water for two years. It depends on how long he was in the ground before he went in the drink.

Either way, it looks like two years is the outer perimeter of the timeline.

I check the Missing Persons reports, but immediately the list

of names coming up becomes too long, and there is no way to

narrow it down until I know whether the killer had a type. Could be all the girls are similar ages, or similar descriptions. Or it could be the other coffins don’t have girls in them at all, but men.

I grab my dry cellphone and the printout of Rachel Tyler, and

head back down to my car.

I’ve barely left the car park when I think better of my initial impulse. It’s the wrong time of the day to show up at somebody’s house to tell them their daughter is probably dead. Most people would think there never is a right time – but there is. It’s the sort of thing you want to do earlier on so they can call friends and family who can come over to console them. Anyway, it may be

Rachel’s ring but it doesn’t mean it’s her corpse.

I drive towards the edge of the city and park my car outside a florist that is open every week night until seven. I need to replace this darkness with some light, yet the first thing I think about is how flowers and death have been mixed together over time as

much as flowers and love.

‘Hi ya, Theo.’ An extremely pretty girl with an easy manner

smiles at me as I go in.

‘How’s it going, Michelle?’ I do my best to smile back.

We make the usual chitchat, then she asks me if I’m after the

usual. I tell her I am.

‘Your wife must really love flowers,’ Michelle tells me, and

I slowly nod.

Michelle picks out a bunch she thinks Bridget will like, wraps some cellophane around the stems, and hands them over. She

writes down the amount in a small book behind the counter. At

the end of the month, like every other month, she will send me a bill.

‘Say hi to Bridget for me,’ she says, and her smile is infectious.

Sometimes I think I could just watch this woman smile for ages.

I head back to my car and rest the flowers in the passenger

seat, careful not to crush them. I glance at my watch. Bridget won’t be in any hurry to see me, so I change my mind and decide maybe I can pay a visit to Rachel Tyler’s family after all. I do a U-turn and drive back in the opposite direction, taking with me a bunch of already dying flowers and a whole lot of bad news.

chapter seven

Averageville. That’s where the Tylers live. All the houses in the street are well kept, but there is nothing special, as if any one resident was too scared to make their house stand out above

another. No huge homes with giant windows, no expensive cars

parked outside, no Porsches or Beemers suggesting a world of big money and high debt. Doctors and lawyers and drug dealers live elsewhere. This is typical living in suburbia, where robberies are high but homicides are low. It’s a pleasant place to live. Sure as hell beats some of the alternatives.

I slow down and glance at the letterboxes, getting an idea early how much further I have to drive. This wasn’t my case when

the bodies floated up. It wasn’t my case when the caretaker took off. But it became my case the moment the coffin opened and

Rachel Tyler’s body made a suggestion that there are others out there who could still be alive if not for my mistake. I glance at the geranium cocktail next to me, and for a few seconds I think about my wife. I like to think that I know what she would want me to do, but I can’t be sure. It’s been a long time since she gave me any advice.

I step out into the light rain in front of a single-storey house that was mass-produced back at the start of the townhouse era.

Things are tidy, but a little run down. The garden has a few weeds; the lawn is a little long; the entire house looks a little tired.

The door is opened by a woman in her late forties, early

fifties. She looks like she has been on edge for the last two years, expecting news at any moment. She is like the house – tidy, neat, but tired.

‘Yes?’

‘Mrs Tyler?’

“Yes …’

I can tell she isn’t sure whether I’m here to sell her encyclopaedias or God, or whether I’m here to bolster or destroy her hopes for her missing daughter. Slowly I reach into my pocket and take out a business card. Her eyes widen and her mouth drops slightly as I hand it across, and when she reads it her mouth firms back up.

She doesn’t seem sure what to say. Doesn’t seem to know whether to be happy or scared that I’m on her doorstep.

‘My name is Theodore Tate,’ I say, ‘and I’m a private

investigator.’

‘That’s what the card says,’ she offers, without any sarcasm.

‘Can I have a few minutes of your time?’

‘Do you know where she is?’ she asks, already sure of the

reason for my visit.

‘This is about Rachel,’ I say, ‘but not directly. Please, if we can step inside, I can tell you more.’

She fights with the beginnings of a sentence; perhaps the

struggle is with the hundreds of questions trying to come out at once, a hundred different ways in which to ask if her daughter is still alive. I bet she’s rehearsed this moment time and time again, but the reality is crushing her, confusing her. She steps back and I move inside.

The hallway is warm and homey. There are dozens of

photographs of Rachel on the walls, ranging over the nineteen

years she spent in this world. There are pictures of her as a baby, her mother holding her tightly. The years have taken their toll on Mrs Tyler. There are shots of Rachel next to a tricycle, in a sandpit, going down a slide. There is a man in some of them,

holding Rachel’s hand, or swinging her at the park, or helping her blow out a cake with eight candles on it. Rachel gets older.

So do her parents. Fashions change and the three grow older, but the smiles are always there, keeping the parents young. One of these photos should have been with her Missing Persons report, but probably Mrs Tyler couldn’t part with any of them. I’m sure Rachel’s bedroom will be just as she left it, the same posters on the walls, her favourite stuffed toys waiting for her on her bed, maybe even a stockpile of Christmas and birthday presents from missed chances. It’ll be like a time capsule.

Patricia Tyler leads me through to the lounge.

‘Is your husband home?’ I ask, praying she isn’t going to tell me they are separated or, worse, that her husband has died from the pain of losing his daughter to a mystery, that he has spent the last six or eight or ten months in the ground.

‘He’s at work. He sometimes works late. Mostly, actually, these days. I should phone him, I guess. Should I?’

‘If you’d like.’

‘What am I going to tell him?’

‘Perhaps we should sit down for a few minutes first.’

‘Sure, okay, sure, I don’t know where my manners are. Can I get you a drink? Tea? Coffee?’ She starts to stand back up. ‘Anything, just name it.’ She’s halfway out of the lounge when she pulls up short; then, fidgeting her hands, she slowly turns back to look at me. ‘I don’t know what I’m doing,’ she says, and starts to cry.

She’s not the only one who doesn’t know what they’re doing,

and I suddenly wish I hadn’t come. I feel the urge to hold her while she cries and an equally strong urge to turn and run back down the hallway and get the hell out of this street. I end up standing still.

‘Please, just tell me why you’re here,’ she asks.

I can no more easily tell this woman her child is dead than

I could show her pictures of the corpse. I cannot tell her about Cemetery Lake, about a woman whose decayed remains look like

they belong to Rachel. I can’t mention the exhumation, can’t detail my swim with the corpses, can’t mention it’s the same cemetery I almost buried my wife in two years ago after the accident. I reach into my pocket and produce the small plastic bag with Rachel’s ring. She takes it without a word, then slowly sinks down into a chair opposite me. For a long time she says nothing.

‘It turned up today in an investigation,’ I say, and she finally manages to pull her eyes away from it and look back up at me.

“Do you recognise it? Does it belong to Rachel?’

‘Where did you find it?’ she asks. ‘Who had it?’

“Nobody had it on them,’ I lied.

‘But how, then?’

“Please, I need to ask you a few questions. The inscription, it says Rachel & David for ever.’

‘Was it David? Did he give you the ring?’

‘No. Nobody had it. I found it.’

‘Where?’

“Please, Mrs Tyler, can you tell me about David?’

‘How did you know to come here?’

‘The inscription,’ I say, but then suddenly realise my mistake.

The only reason I’d check Missing Persons would be if I believed the ring belonged to somebody who was dead. Mrs Tyler, thank

God, doesn’t make the connection.

“David gave it to her for her birthday.’

“Is David her boyfriend?’ I ask, careful not to say ‘was’.

“I’ve already told the police all I know’

‘But I’m not the police,’ I say, ‘and that means I can approach things differently.’

‘You think she’s dead, don’t you.’

I think of the flowers in the passenger seat of my car, and

I regret not driving out to see my wife first. I could have talked to her. Told her about my day. Told her how much I missed her.

Could have held her hand and told her everything.

“I don’t know,’ I say.

Then what makes you think you can help her?’

It’s interesting she has asked how I can help Rachel, and not her and her husband. Interesting isn’t the word. It’s devastating.

This woman isn’t just holding out for the possibility that her daughter is alive; she’s holding on to the reality of it. But the question is more than that. It makes me think of exactly what

I can do to help Rachel: nothing. Not now. I can’t even help the others who have followed.

“I would imagine Rachel wants as many people helping her as

she can get.’

She nods, then starts telling me about her daughter, and

I realise I could be anybody in the world and she’d still be happy to speak about Rachel. She’d probably be the same way if I was at the door selling encyclopaedias or God. She talks for nearly twenty minutes and I don’t interrupt her. I know what it’s like to have lost somebody. I know what it is like to hold out hope.

False hope is cruel, but perhaps not as cruel as no hope at all. It’s a judgement only those who have been there can make.

‘And David?’ I ask, after she has told me what she can about

Rachel’s life, including in detail the days before she disappeared.

‘What can you tell me about him?’

“I thought he knew what happened,’ she says. ‘For those few

weeks I was sure she was living with him. See, they were living together, but not really. All her things were here, are still here, but she wouldn’t come home for days on end. When we didn’t see

her for a week we tried contacting her, then him, but he said he hadn’t seen her. I thought he was lying, and that he was shielding her from us for something we must have done. But I knew,

I knew something wasn’t right. I don’t know how, but I just knew.

So Michael, my husband, called the police. We filed a Missing

Persons report. We hadn’t heard from her in nearly a week. It

wasn’t like her.’

‘What happened when the police spoke to David?’

‘Nothing. They said they had no reason to believe he was lying.

Still, I wasn’t convinced. I would go to his house at different times, but there was never any sign of her. I would knock on his door in the middle of the night. After a while I began to see that David was just as distraught as we were, and I started leaving him alone. I don’t know if he really believes Rachel is still alive.’

I throw a couple of names at her. Bruce Alderman and Henry

Martins. She shakes her head and tells me she’s never heard them, and asks me why. I tell her the names have come up but I’m

not sure where they fit into it, and that it may be unlikely they even do. She gives me a list of Rachel’s friends, places she liked to go, photographs of her, people she worked with, David’s

address. She’s giving it all some real serious thought, hoping for a connection, hoping she is going to mention a name that’s the key to getting her daughter back.

She walks me to the door. She seems reluctant to let me go. I

feel guilty I’ve deceived her, that I’ve given her more hope today than she had yesterday, and the guilt becomes a sickening feeling that makes the world sway a little as I make my way to the car. The police will identify Rachel Tyler. They will come here tomorrow or the next day, and they will tell Patricia that her daughter is dead. I can’t stop it from happening. I can’t prepare her for it.

It’s getting close to eight o’clock and within the next twenty minutes it will be dark, the thick clouds bringing the night earlier than usual for this time of year. The flowers in the front seat still look fresh enough to keep on growing. I start my car and pull

away, the small voice inside my head questioning what in the hell I am doing, and the bigger voice, the one I use every day to justify my actions, telling me I have no idea.

chapter eight

Perception is a funny thing. Especially when you’re dealing with luck. Somebody who survives a plane crash is considered lucky. Is he considered lucky to have even been on that flight? Or unlucky?

Does the bad luck of being seated on a doomed flight cancel out the good luck of surviving? I don’t get it that people are lucky to have lost only an arm.

My wife was lucky. That’s what people say. An inch here or

a second or two there, and things would have been different.

I would have ended up burying her, and the flowers I keep buying would be going to a grave. Inches. Seconds. Luck. Good luck for her. Good luck for all. It doesn’t add up. She wasn’t lucky. Not at all. Wasn’t lucky when the car ploughed into her; wasn’t lucky that her head hit the footpath at forty kilometres an hour and not fifty. Wasn’t lucky when her legs were shattered, her ribs broken.

Lucky to have lived, yes, but not lucky.

The care home is out of the city where suburbia kicks in and

city noise dies away. It covers five hectares of land, widi grounds scenic enough to be used for a wedding. The buildings are forty years old, grey brick with the occasional flare of polished oak windowsill – a combination of bad ideas or perhaps good ideas that didn’t work. The driveway is long and shaded by giant trees that flourish in the summer and look like skeletons in the winter.

I pull up outside the main office and for a few seconds try to imagine that this world hasn’t gone mad.

The main doors are heavy and made from oak, as if to stop the

weak from leaving or tempt the grieving to turn away. The nurse behind the reception desk smiles at me. Her dark red hair matches the sunset in the painting behind her.

‘Hi, Theo. What have you done with the weather?’

I fake a smile of my own, the type anybody with social skills

would apply when the weather suddenly becomes the topic of

conversation. ‘Tomorrow I’m organising sun. God owes me a

favour.’

She nods, maybe agreeing that yes He does. ‘Flowers for me

this time?’ she asks, like she always does.

The nurses and doctors are always nice, always friendly, always professional, their questions and pleasantries always cliched. The alternative is unthinkable. You’d ask how their day was going and they would tell you the truth and you’d never come back.

‘Next time,’ I say, which is what I say every time. ‘How is

she?’

‘She’s doing fine, Theo. But what about you? Is that you I saw on the news?’

“Yeah, it’s been one of those crazy days.’ A fairly accurate

summation, I feel.

She nods. ‘Every day this city shows us a little more how things don’t make sense.’

‘Sometimes I think Christchurch is broken,’ I say, ‘and nobody is ever going to fix it.’

I walk down the corridor, passing empty seats and closed

doors and a nurses’ station that looks empty but most likely isn’t.

The entire floor is speckled green linoleum, the sort that is easy to clean blood and vomit and shit off and will last two hundred years. The day is cold but the air in here is comfortable. It’s always comfortable, and so it ought to be. Some of the people in care here don’t know how to complain, and some who do know simply don’t have the ability any more. There are more paintings with water and sunsets, peaceful scenes that are perhaps supposed to help calm the residents here before they move on from this

world and into the next. There are pots full of artificial plants.

And there are decorations for the people who come here who are on the verge of losing it.

I climb a flight of stairs, and halfway down another corridor

I stop at Bridget’s room. The door is open. She is sitting by the window, looking out at the misty rain and the trees and the lack of good weather that the nurses mention every time I arrive. She seems interested in all of it. I don’t know whether she hears me come in. I close the door behind me. She keeps staring outside.

‘Hey babe, I’ve missed you,’ I say, but she doesn’t answer. I take yesterday’s flowers out of the vase and put today’s flowers in. She doesn’t notice. She doesn’t notice as I shuffle them around in an attempt to make them look nicer. I sit in the chair next to her and take her hand in mine. It’s warm. It’s always warm, no matter how cold the room gets. I’m glad for it, because it helps remind me my wife is still alive.

She occasionally blinks as I tell her about my day. There is

no expression on her face as I run a brush through her hair,

stroking it over and over, searching for the recognition that isn’t there. She does not laugh when I tell her how I slipped into the water. She doesn’t chide me for not telling Patricia Tyler that her daughter has been dead the entire time she has been missing.

Other noises, the shuffling of patients, the squeaking of caster wheels, come from the care home which, for the last few years, I have quietly nicknamed ‘Death Haven’. I’m not sure why I’ve

come up with the name. I’m not sure whether thinking of it as

Death Haven has made it more personal to me or less. Every day I have this romantic notion that I will come in here and Bridget will look up at me and smile. Every day. But she doesn’t. I hold onto the hope, I have become attached to it sentimentally, in the same way Mrs Tyler has become attached to the idea her daughter has run away and is living the perfect life in a perfect town and is so perfectly happy she just hasn’t had the chance to call.

I keep talking until my throat is sore and I’m out of words.

Bridget has remained in her catatonic state the entire time, happy in the world she is in, or perhaps sad; I wish I had a way of

knowing. The window and the trees beyond hold for her the

same fascination as they have done every day for the last two

years. I feel exhausted, as I always do when I purge myself of the day’s events. The silence in the room is peaceful, and in these quiet times I often think that I would be better off if I could be catatonic too, unknowing and unfeeling, and keeping Bridget company. I sit holding her hand for a few more minutes, then

I stand, pulling her hand up slightly. She comes with me and

steps towards the bed. Her actions are involuntary, her body just following the motions. She can move from the bed to the chair, and back again. Sometimes the staff will find her standing in

the corridor, motionless, and twice she has made it down into the foyer. Guide a glass up to her lips and she can drink. Raise a fork to her mouth and she can eat. But she cannot fend for herself, cannot speak, cannot look at you with an expression that suggests she knows you are there. Everything is a thousand miles away, and her eyes are fixed on that point in the distance, continually searching, searching, but never finding.

She lies down. I kiss her on the side of her cool face – her

hands are always warm, her cheeks always cool – then slowly

make my way from her room. I don’t turn back. I never do, not

these days. I will see her tomorrow. And the day after that. And the day after.

Patricia Tyler isn’t the only person in this city playing the

waiting game.

Outside, the cold air feels like silk against my face. I stand next to my car for nearly five full minutes. I stand doing nothing as the rain dampens my jacket. I’m not even really sure whether I’m thinking about my wife or dead girls or bad luck and bad omens, Until finally I find the strength to drive away.