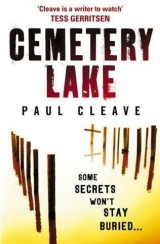

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter thirty-one

‘Driving under the influence. Reckless driving. Jesus, you’re in some real trouble,’ Landry says. He’s wearing the same clothes as last night. They’re all wrinkled up, which means he probably slept in them. He looks even more tired than the last time I saw him.

‘How’s the girl?’

‘Stable.’

‘Is she going to make it?’

‘Maybe you should have been concerned with other people’s

safety before getting behind the wheel drunk.’

‘Is she going to make it?’

“I don’t know. Probably’

‘Probably? Don’t you care?’

‘I care, you son of a bitch.’ Landry bangs his fist down on the table. ‘I’m the only one in this room who does, and what you did last night proves that.’

I look away.

‘What in the hell were you doing?’ he asks.

‘Nothing.’

‘You’re doing nothing at that time in the morning? Come on,

Tate. You were at the church again.’

“No, I wasn’t.’

‘In fact you were. I saw you there. Lots of people did See

it was on TV That reporter of yours showed it. She did a great job of it, showing you right outside the church breaking your

protection order.’

“I was getting my car.’

‘You were breaking the law.’

‘Come on, Landry, you could probably see me climbing into

the damn thing. And I left straight away’

‘Then what? You go back a few hours later and decide to

watch Father Julian? What’s the big plan here, Tate? Are you that desperate to kill yourself?’

I wonder if Father Julian heard the crash. I wonder if he looked in his rear-view mirror and decided he had more important things to take care of.

‘What’s going to happen now?’

‘Two things. We’re going to talk to Father Julian. We’re going to ask him if you were there last night, and if he says you were, you know what happens: we’re going to take his word for it.

We’re going to ask him once and let him think about it, and if he says yes we’re not even going to ask him if he’s sure about it. You get my point?’

“I get it.’

‘But first you’re going to be charged with DUI. You’ll be

escorted down to court later this morning. I’m going to do you a favour and let you wait here rather than back down in the cells. But it’s the last favour I’m ever going to do for you.’

He leaves me alone. I rest my head in my arms and manage to get two hours sleep before the same two guys who brought me upstairs take me out to a patrol car and drive me to the courts. The day is wet and cold and grey. I’m kept in the holding cells with a whole bunch of people whose futures are about to be determined by the same people about to determine mine. My headache hurts and so do the wounds. I’m given a court-appointed lawyer and We get to speak for about two minutes before my arraignment.

In court I stand in the dock with my head down and listen to

the charges. I plead guilty. I know how it all works. This is the same thing that happened to Quentin James. The judge sets bail and says that if it can’t be paid they will hold me until sentencing, which is set for six weeks away. I can’t pay the bail. I’m taken back to the cells, the plan being that sometime in the middle of the afternoon I’ll be transferred to prison. Christ I need a drink.

I don’t know how much time passes before one of the court

security officers opens up the holding cell and tells me to follow him.

‘Your bail’s been made.’

‘Made? Who by?’

‘Your lawyer.’

‘I don’t even know my lawyer.’

‘Yeah, well, it’s not the same guy’ he says, shrugging. ‘You got a new lawyer now. Means you might have a chance at a real legal defence.’

A guy in an expensive-looking suit comes to greet me. The

suit is so sharp it’s hard to believe he’d dare sit down for fear of it wrinkling, but it isn’t as sharp as his smile.

‘Theo,’ he says, stepping forward and pumping my hand so

vigorously it’s suspicious. ‘Glad to finally meet you.’

‘Glad?’

‘Well, of course the circumstances are awkward. Not dire, but with your past they shouldn’t be anything we can’t handle.’

‘I’ve already pled guilty’

‘Yes, of course you have, and that was perhaps a mistake,’ he

says. ‘But the sentencing is what’s important. Your history, the reason you were drunk, will go a long way towards having them

reduced.’

He introduces himself as Donovan Green. He stands over my

shoulder as I sign a series of forms before I can go. The officers hand me over my wallet and my watch and my phone. The phone

is flat.

Green walks me outside towards a black BMW in the far corner

of the parking lot between a high concrete wall and a dark blue SUV with tinted windows and mud splashed up the sides. The

day is cool and the breeze makes the exposed grazes on my body sting. I pick up the pace a little to get to his car faster.

‘Who hired you?’

‘You mean you don’t know?’

“I have my suspicions,’ I answer, but truthfully I don’t have

any idea.

‘You still have friends in the department,’ he says, and the line is starting to sound all too familiar.

“I want to go to the hospital.’

He pauses. ‘The hospital? Injuries hurting, huh?’

“I want to see the woman I hurt.’

“I don’t understand. You want to see her?’

‘I want to see how she’s doing. I’m the reason she’s in there.’

‘I’m well aware of why she’s in there,’ he says, a little too

harshly. ‘Look, Theo, it’s just not a good idea.’

“I need to see her.’

He shrugs, like he no longer cares. ‘Then let’s go.’

He leads me to his car. It turns out it’s the dark SUV and

not the BMW He puts his briefcase down while he digs into his

pocket for his keys. He checks one, then the other, and I know how the routine goes when you can never find them.

‘Must be in the briefcase,’ he says, and he pops it open. ‘Yep, here we go.’

He unarms the car and the doors pop open.

‘Hop on in.’

I climb inside. The interior is comfortable and warm. Green

plays around with his briefcase before opening the door. When he does, he leans in and points something at me.

‘Whoa, wait a …’

But it’s all I can say before he pulls the trigger. My body jerks back, my head cracks into the window beside me, and the world

goes black.

chapter thirty-two

The blackout lasts only a moment. I come to and the pain in my head from the impact helps to numb the pain flowing through

my body, but only for a few more seconds. The two catch up and the electricity raging along my spine from the taser gun takes over. Green says something but I can’t hear him. Two barbs are buried into my chest, delivering hundreds or even thousands of volts. He turns the gun off but there’s no relief. He rips the barbs out. The pain drops but I still can’t move. Blood drips from the barbs onto my shirt. He wraps the cords around the unit and

drops it into his briefcase. Then he moves into the seat behind me, pops my seat so I’m leaning back, and drags me into the back of the SUV

He takes some plastic zip-lock ties from his briefcase, rolls me onto my front, and a moment later I can hear the little notches clicking into place. I can’t fight him. He moves back to the front.

The engine starts, and we roll forward. I try to sit up but can’t.

The tinted windows mean nobody can see in. I can’t speak and

don’t know what I’d ask if I could.

I can hear other cars. I can hear people talking on the street.

The hustle and bustle of city life. But my lawyer doesn’t say a word. He’s on a mission now. I can smell upholstery and sweat, and can taste blood.

We drive for a few minutes before I start to speak. It happens around the same time the pain starts to fade and the cramp in my muscles starts to relax. I try to struggle against the plastic ties but it’s no good. They dig into my wrists and ankles.

‘Where are we going?’

‘You tried to kill my daughter.’

‘What?’

‘Shut the fuck up,’ he says, and suddenly I realise that the

transition from Theodore Tate’s life into Quentin James’s is

complete.

‘Where are you taking …’

‘I said shut up!’ he shouts, and he pulls over and reaches

towards me.

Christ, there’s a needle in his hand.

‘You struggle and it’s only going to be worse.’

I struggle, and the needle breaks off in my arm before he can push any of the fluid into me.

‘Fucker,’ he yells, then he starts clubbing me in the head with something, I don’t know what, and everything goes dim as the

darkness rushes back.

chapter thirty-three

I have no idea where we are. In the woods, somewhere. He must

have carried me here from the SUV Or more likely dragged me,

since the backs of my shoes have a build-up of mud and leaves on them. The surroundings remind me of where I was two years ago

when I was the one holding the gun and not the one under the

barrel of it. I am lying on my side, the wet dirt cold against my body. There are hundreds of trees and ferns and rocks, and there is a light rain. My cellphone is in a dozen pieces on the ground ahead of me.

The world comes into sharper focus and that’s a problem,

because in the centre of my view is my lawyer. He’s no longer

wearing the suit. The gun looks like a 9mm. I figure it’s loaded to the max and this guy looks like he’s in the mood to prove it.

He notices me staring at the gun, then he turns it in his hand and looks at the side of it, as if he’s seeing it for the first time.

‘It’s amazing what you can get for a few thousand dollars when you’re motivated enough,’ he says, ‘and are prepared to spend a few hours in the worst part of town. Guns, tasers, there’s no limit when you’ve got the cash. And the desire.’

My hands are still bound behind me. I tuck my legs beneath

me and manage to get onto my knees. The taser pain has gone,

but not the pain from the beating the guy gave me to knock me

out. I have to blink heavily every few seconds just to keep things from going fuzzy, and it’s a struggle to stay balanced. The broken needle is still in my arm. Blood is running down my face. It’s getting dark. Must be around four o’clock. Maybe five.

‘What do you want?’ I ask.

‘What do you think I want?’

I remember what he said in the car. About his daughter.

‘It was an accident. I’m sorry’

‘You think being sorry negates all of this? You think if she dies your sorries will help me sleep at night?’

I close my eyes while he talks to me. His words are very similar to the ones I said to Quentin James, only for him I didn’t use a ‘what if because Emily was already dead. I wasn’t waiting on

more information on which to base my decision. Nothing was

going to change. One difference is I didn’t bind Quentin with

plastic ties. I held him at gunpoint and made him walk. I made him carry a shovel because I wanted him to know how it felt to be a victim. I wanted him to know that the feeling he had that he was about to the was the same feeling I’d had every day since the accident and what I would feel every day for the rest of my life.

Hell, for me it was worse. I already had thed, and it was because of him. I made him dig a grave, and all along he cried and told me it was an accident, he told me he wished he could change time, he told me it was Quentin James the drinker who had killed my

daughter and not the man holding the shovel. The man holding

the shovel was going to get better. He was going to seek help. He would go to jail and he would live with what he had done, and

he would get better.

“I’m a different person when it happens,’ he told me. ‘I’m no

longer me.’

But I didn’t care; my wife was no longer what she had been,

and my daughter was no longer alive. I watched as the sweat

began to expand in circles from his armpits over his shirt, even though it was cold out. Dirt was sticking to his face, to his hands; He rolled up his sleeves and dirt began to stick there too. I told him it was too late, that it didn’t matter what he said now, that being sorry wasn’t going to change the past and wouldn’t prevent the future. He cried. He begged for his life. He tried to make me change my mind, but it didn’t matter. I was never going to let his justifications and sick excuses stop what was coming, and I’d made that decision before heading out there. I had to. I had to. It was the only way to go through with it, and the only way to save others from him.

Now my perspective is changing. Maybe the same damn thing

that got me here is the same thing that happened to him. I never looked into his history. Never learned whether his family had

died, never learned what drove him to drinking. There was way

too much anger for that. He stood in the grave and he cried as I levelled the pistol at him. He told me he was sorry, and I told him that was enough, that I didn’t want to hear any more, that it was time to take responsibility. Through all his fear there must have been some hope I was going to let him go. I was hoping he would accept it, that he would shut up and make peace with his maker and just accept it. But he didn’t.

Quentin James was still begging for his life when I shot him in the head. It didn’t feel as good as I thought it would.

I shuffled his body so it was nice and snug in the grave he’d

dug, and then I buried him. I walked away without giving him a prayer or spitting on his grave. There was just a smooth transition between shovelling dirt and then turning away. A smooth

transition between going from father to killer. I carried the shovel back to my car, drove away and have never been back.

Unless I’m back here now. These could be the same woods.

‘It was an accident,’ I repeat.

‘You had a daughter,’ he says. ‘It’s all over the news now. How the hell can you, of all people, drive while completely tanked?’

‘There’s no shovel,’ I say.

‘What?’

‘You should have made me bring a shovel.’

‘What for?’

‘What do you think?’

‘You think I care whether I bury you or not? You think I care

whether you’re ever found?’

‘You should do.’

‘Why?’

‘Because you’re going to throw away your life. I deserve what

I get, but you don’t deserve to be punished.’

He takes a small step back. I’d rather he’d come forward. I’d

rather he was pointing the gun at my head. Rather he did us both a favour and got this over with.

‘What?’ he asks.

‘Just pull the trigger.’

‘I’m going to.’

‘Yeah, you’re saying it but you’re still talking about it. Look, for what it’s worth, I’m sorry. But if you’re waiting for me to beg for my life, I’m not going to. You might want that, but it’ll only make it harder. It’ll haunt you. The fact is you’ll shoot me and you’ll discover it wasn’t satisfying. You’ll feel nothing. At least that’s how it was for me.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Could be different for you. Your daughter’s alive, right?

Rather than being with her, you decided to come out here and be with me. You’ve got your priorities wrong. You’ve fucked up your timing. You could have brought me out here any time.’ There’s

a wedding ring on his finger. ‘Your wife and daughter, they need you now.’

‘Shut up. Don’t tell me what my family needs.’

‘What’s her name?’

‘What?’

‘Your daughter. Her name. I don’t know anything about her.’

‘You don’t deserve to know it.’

‘If you’re going to kill me, I think I ought to know her

name.’

‘Fuck you.’

‘Just pull the trigger.’

‘What’s your hurry?’ he asks.

202

“I don’t know. I really don’t know.’

‘You don’t think I’m going to do it, do you?’

‘What do you want me to say? You want me to say something

that will sway your decision? How about this? Your daughter

could have died, but she didn’t. She’s fighting for her life and she’s still with you. Does that make a difference? Of course it does. You’d have to be stupid not to recognise it. Do I deserve to die for that? That’s up to you. Me, I’m at that stage where it doesn’t matter either way’

‘How dare you.’

‘What?’

‘How dare you kneel there and act like a goddamn martyr.

How dare you act like you’re the one who’s the victim, like you’re the one having a bad day. Don’t you get it? Don’t you get what you almost did?’

‘Of course I do.’

‘Yeah, you’re good at taking responsibility, right? But all you’re doing is trying to mess up my reasons for bringing you out here.

Why don’t you just shut up, huh? Shut up and let me decide for myself what I’m going to do. This is my life we’re talking about.

My sixteen-year-old daughter you tried to kill. How dare you

kneel there acting as if you don’t fucking care whether you live or die. Show some fucking respect and at least beg for your life, right? Make me feel something. Make me want to hate you even

more, make me want to hate what I’m doing.’

‘I’m sorry about your daughter.’

‘Emma,’ he says. ‘Her name is Emma.’

‘My daughter’s name is Emily’ I say, as if she’s still alive. At first I’m not sure why I say it, but then it comes to me. I want to live. I don’t want to die out here. I want the chance to make things right.

‘Emma. Emily,’ he says. He doesn’t expand on the thought,

but he’s really thinking about it. Thinking hard. Maybe drawing some parallels between the two names.

“I still have a wife,’ I add. ‘Her name is Bridget.’

“I know. And I’m sorry about what happened to your daughter,’

he says, ‘but that makes what you did even worse. Don’t you get that? It doesn’t make me sympathise with you, it only makes me angrier.’

And so it should.’

‘There you go again,’ he says. ‘You’re trying to diminish the

moment.’

‘Are you really a lawyer?’

‘What?’

‘You talk like one.’

“I’m a divorce lawyer.’

And when you came to the prison, you gave them your name,

right?’

“I had to so I could bail you out. But they don’t know I’m the one who brought you out here.’

‘You don’t think they’ll figure it out? You don’t think they’ll work out that the lawyer, who they’ll soon realise is the father of the girl I hurt, was the last person to have seen me? And you went into town and bought yourself some black-market weapons. That

shows premeditation. That’s bad for you.’

He thinks about it for a few seconds. ‘Fuck,’ he says.

‘See, you’re being driven by emotion, not logic. You should

have known that. It’s a pretty simple equation, and you looked right over it. Don’t do this. Don’t throw away your life.’

He takes a step forward, raises the gun so it’s pointing at

my head. But the cold and the nerves are too much for him to

control, and his hand is shaking badly. His breathing is ragged.

He’s fighting with the same decision I had back when the roles were reversed, only it was a decision I didn’t fight with. I was comfortable holding a gun. I just aimed and fired.

“I’m going to do it,’ he says.

‘You’ve got no argument from me.’

‘Shut up, damn it. Let me think.’

I stay on my knees and I force myself to keep looking at the

gun, and it terrifies me. His face is taut with pain, his mouth forms a grimace as he runs through the scenarios in his mind.

One, he walks away with blood on his hands; the other, he walks away feeling a little unsatisfied. I decide against giving him any more advice. He’s a big boy. He can make up his own mind.

It takes him a minute. It’s painful to watch. Painful to stare at the gun and wonder if he’s about to pull the trigger. In the end he takes a step back. Then another. But he keeps the gun pointing at me.

If she dies,’ he says, ‘we’re coming back out here.’

He backs away, turns, and then I am alone.

chapter thirty-four

I lie on my side and bring my knees to my chest and squirm

around to bring my hands up under my feet. It doesn’t work. I roll around, but the plastic ties are securing my wrists, and there isn’t enough room to stretch my arms all the way around. I get back

to my knees and sit down, stretch my legs out, and start rubbing them back and forth across a mossy rock. The moss scrapes away and exposes an edge for me to saw against. It takes only about a minute for the binding to snap through. I do the same with my

wrists, then pull the syringe needle out of my arm. I toss it on the ground next to my busted cellphone.

I head in the same direction as the lawyer. My clothes are damp and cold. Donovan Green, if that’s his real name, may not have finished me off with a bullet, but that doesn’t mean I’m getting out of here alive. Unless I can rub some bandages together and make a fire, I’m going to freeze to death out here. The trees

and ferns brush at me, scraping my hands and snagging my

clothes. Small grazes lead to cuts and then to bleeding. My head is still throbbing, and my chest is sore from the taser barbs. My hand hurts the most: the finger with the ripped off nail feels as if it’s on fire.

The lawyer has left a path. I keep my eyes on the ground

and follow the twin lines that have been cut into the dirt by my dragging feet. I figure he would have parked nearby, not wanting to drag me far in these conditions, and a moment later I hear a car pass by. I pick up the pace and a minute later break through some trees and onto a road. Red tail lights are disappearing in the distance.

The mud has had a snowball effect on my shoes, and I kick

and scrape them against a tree to break it off. I dig my hands into my pockets and start walking. No other cars come past as I walk in the same direction as the one I saw. I still don’t even know where I am. My teeth are chattering and every minute or so my

body gives an involuntary spasm that lasts a couple of seconds.

Quentin James would have had a similar walk if I’d have let him, except his would have been in nicer conditions. I brought him

out on a sunny day, a warm day, as sure as hell a nicer day

than today.

I reach an intersection and a couple of cars go by. I wipe my

sleeve at my face to clean away some blood. I start to have an idea where I am. Nobody pulls over to offer me a lift, and I don’t put my bite-scarred thumb out to ask for one.

The road heads towards the city and, eventually, towards home. It’ll be a fifteen-minute trip if I was driving. Walking, i’ts going to take me a few hours. At least. If I was driving I’d be doing eighty kilometres an hour out here.

The day becomes evening and the evening is dark. The rain

begins again. It gets heavy for a while and washes the mud and dirt down my body before lessening to a drizzle. My joints grow increasingly numb. My feet feel like slabs of ice. The walk is a sobering end to a day and to a way of life.

It’s almost midnight when I get home. I don’t have my keys and I hadn’t even thought about them until now. They’re in my car, and my car is in an impound lot somewhere, or maybe a wrecker’s yard. I sit down on the front step and lean against the door. I’m exhausted. The soles of my shoes have small stones and slivers of glass buried into the tread. I feel like I could fall asleep here.

rest for a few minutes before getting up and walking through

to the back yard. I grab a rag and a roll of duct tape from the garden shed, wrap the rag around a small rock, put the tape across the window to muffle the sound, then smash the glass.

While the shower warms up I find a bottle of bourbon and sit

down in the living room. I wonder what Quentin James would

have done had I let him walk home. Would he have taken a drink?

I figure he’d have needed one. Would he have kept on drinking

until one day he killed again? I carry the bottle into the kitchen and pour its contents down the sink. I scour the house for more bottles. There are plenty of them, a few with just enough in them to make me feel warm if I allowed it. I tip them all down the

sink, and then I drop every single empty in a recycling bin and sit them outside. They overflow and I have to stand the rest on the ground.

I strip out of my clothes and throw them into the washing

machine. The shower is still going, steam flooding into the

hallway. I walk around the house, picking up other clothes I’ve worn over the last few months and I stuff as much as I can

into the machine. I set it going. I head into the bathroom, and am about to step into the shower when knocking comes from

the front door. I wrap a towel around myself and go out into the hallway.

A red and blue light is arcing through the windows and

lighting the walls. There are two possibilities. One I can live with. It means one of my neighbours made a call because they

heard somebody breaking in. The second one means Emma, the

sixteen-year-old girl I hurt last night, has died. Maybe I poured away all that bourbon too soon.

I’m nervous as I head up to the door. It’s Landry.

‘You’re going to have to come with us, Tate,’ he says, ruling

out possibility number one.

‘Just tell me. Just get it over with.’

‘It’s about Father Julian.’

‘What? Look, this is bullshit. I haven’t been near him all day’

‘You’re coming with us.’

“I don’t understand.’

‘Jesus, Tate, it’s simple. Don’t stand there and pretend you

don’t know.’

‘Don’t know what?’

He sighs, and slowly shakes his head. ‘Come on, do you really

want to play this game?’

‘Humour me.’

‘We went to speak to Father Julian this afternoon. We were

going to ask him if you were there last night. And I’m sure he would have said yes.’

‘Would have?’

‘See that’s the problem. He’s dead. Somebody murdered him

last night. And right now my money is on that somebody being

you.’