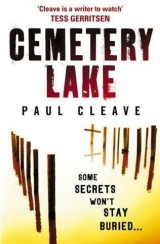

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter forty-six

‘What the fuck do you want?’

‘Your help,’ I say.

‘You’ve got to be kidding.’

It’s still early Saturday morning. I should have called Landry or Schroder, but instead I’ve driven to the hospital. I need to work my own way, especially if I’m to get the opportunity to dig Sidney Alderman out of his wife’s grave. There’s no way I can

do that if I’m in custody answering questions about how I know what I know.

Visiting hours on a Saturday morning mean the corridors are

full of disoriented-looking family members and friends. The air has the sickly smell of disinfectant and vomit, but you get used to it pretty quick. Emma’s father pushes me in the chest and I fall back a few steps. I don’t put up a fight. He advances towards me.

A few people look over but no one does anything. “I should have killed you,’ he says.

‘There’s still plenty of time for that,’ I say, holding my hands up in surrender. ‘At least listen to me before you get kicked out of the hospital for assault.’

‘You’re the goddamn reason we’re in here,’ he says. ‘They’d

kick you out and give me a medal.’

‘Maybe you should hear me out,’ I say. ‘I have some interesting things to say. You are my lawyer, remember. You signed me out.

That means it’s your job to talk to me. If not, I’ll go to your firm and find another lawyer. I tell them all about you. All about that trip we took.’

‘Fuck you.’

‘You didn’t think it through, did you? I’m your responsibility until that court date has come and gone. See, you figured I’d be dead by then and it wouldn’t matter. But now it does. Help me out and I change lawyers. Nobody has to know what happened.’

‘Go to hell.’

‘Think about it. Calm down and think about it.’

He takes a step back and stands in the doorway of the ward.

He looks at his daughter. She’s awake and hooked up to a bunch of machines. There is a TV going. She glances from the TV to

her father. Then his wife, an attractive blonde woman dressed

perhaps a little too formally for a hospital, looks at me too. She knows something is going on but doesn’t know what. There is

no recognition. If there was she’d start screaming. She’d claw out my eyes. My lawyer turns back towards me.

‘What do you want?’

I explain what I want, and the whole time he shakes his

head.

‘Impossible,’ he finally says.

“I thought lawyers thrived on the impossible.’

‘We thrive on sure-things.’

‘But you make more money on the impossible.’

“No judge will sign off on it.’

‘that’s the point, right? You don’t need one to. Just get the

template for me and I can do the rest. Then you don’t hear from me again. Look, nothing is going to happen. I’m never going to tell anybody where I got it from.’

‘No.’

‘No?’

‘that’s right,’ he says. “I go to my boss and explain what I did to you, and he understands. He’ll tell me he would have done the same thing.’

‘And maybe I go to the papers and tell them about you. Even if they don’t believe me, it still puts your name in disrepute. People might sympathise with you, they might even relate, they’ll probably wish you’d pulled the trigger, but that’ll be on their mind every time they’re passing you over in preference for another lawyer.’

‘Won’t happen. People will love me for it.’

“I think you have a great misunderstanding of what people

love. You prepared to take that risk?’

He looks back at his wife. She’s looking a little concerned, but I bet she doesn’t know about the field trip her husband took me on.

My lawyer planned on killing me. He didn’t succeed, and I’m

here to pull him deeper into the world he stepped foot in. Only I’m also giving him an exit. He just needs to see that – and, being a lawyer, I figure he will.

‘Just the template,’ he says.

‘that’s all.’

‘It’ll take an hour.’

‘I’ve got time.’

I head upstairs to the cafeteria and order some coffee and a

couple of chicken and egg salad rolls. There are a few newspapers lying around. There is nothing in the front-page photo of Father Julian to suggest that he was living a secret life. There is a stock quote from somebody high up in the police: We are following up on leads but can’t release any further details at this time. They have a murder weapon and no suspect. There is another article

a few pages in. It details Father Julian’s history. He was assigned to the church thirty years ago. He was born in Wellington to a middle-class family, he excelled academically at school, he joined the priesthood at twenty-one. His mother died twenty-five years ago, his father is still alive. There are facts and figures that would be thrown out of whack if I were to tell them Father Julian fathered all those children.

I read through the rest of the newspaper but don’t get to the

end before Donovan Green is back. He pulls out the seat opposite me, seems about to sit down, then changes his mind. He doesn’t want to sit with a guy like me. He reaches into his jacket pocket and pulls out an envelope. He sits it on the table and keeps two fingers on it.

‘We’re done now, right?’ he asks.

‘That depends.’

‘On?’

‘On whether that’s a Christmas card in there or what I asked

for.’

He slides it across. I open it up and take a look at the court order. I’ve seen them before and know it’s the real thing.

“I don’t ever want to see you again,’ he says.

‘For what it’s worth, I’m sorry’

‘Yeah. Lawyers hear it all the time, right? Everybody’s sorry

after the event.’

I don’t answer him. He stares at me for a few more seconds,

and I can tell he’s thinking about how life would be different for him right now if he’d killed me.

‘Worse,’ I say.

‘What?’

‘It’d be worse. Trust me. You did the right thing.’

He nods, seeming to understand, then turns and walks away.

I push the newspaper aside, finish my lunch and head down to

the car.

chapter forty-seven

The traffic out near the care home increases a little on weekends, but it’s not like visiting hours at the hospital. The hospital is a temporary thing. Relatives and friends don’t mind making the

visit because they only have to go a few times. Out here it’s

permanent. The visits don’t fit in as often as they ought to in the schedule of day to day life. The care home is too depressing, even with its brightly coloured artworks and flowers. There’s no covering up the pain and misery here.

I sit with my wife and hold her warm hand. She looks out at the rain but doesn’t see it. It’s hard to imagine that a person doesn’t look forward to certain types of weather. Sun, rain, storms: they don’t even register.

‘Things are getting better,’ I tell her. ‘I’ve stopped drinking, but it’s hard, I’ll admit that. It’s hard to describe. Without the drink I feel like a part of me is missing. I feel like I need to have one more just to say goodbye to it. One more won’t hurt, right?

Just to say goodbye. I think of you all the time. I wish things were different, but I want you to know that you’re helping me

get through this. You’re the reason I’m getting my life back on track.’

I tell her this, but I don’t tell her that it’s only been a day.

Maybe in a week my speech will be different. Maybe I will be

able to take that drink to say goodbye and not get pulled into the abyss. Maybe.

Back downstairs, Carol Hamilton is behind the desk.

‘It’s good that you’re starting to come back,’ she says.

“I miss her.’

“I know you do. It’s an awful situation, and it’s worse for you than it is for her. I just wish there was more I could do.’

“I know. I make the same wish every day’

She doesn’t answer, and I let the silence fall down around us

like a shroud, letting us think our own thoughts on how life could be different.

“I hate to ask,’ I say, snapping her out of it, ‘but have you got a computer I can quickly borrow? And a photocopier?’

“I … umm …’

‘It will only take me a minute or two. I promise.’

‘that’s fine, Theo. Follow me.’

She leads me into an office that has more photos of family and drawings from children on the walls than anything else. There

are so many personal items that it’s easy to see the people who work here need to stay grounded to a different kind of reality, one where the bad things that happen in life haven’t extended to their own families. I’m about to play around with the computer and

photocopier when I spot a manual typewriter. I can’t remember

the last time I saw one.

‘One of the nurses,’ Carol says, ‘is still very old school.’ She doesn’t explain any further and she doesn’t need to.

I wind the court order into the typewriter, and type in the

priest’s name and location of the bank in the provided space.

Then I sign it with some unidentifiable scribble. Carol Hamilton watches me the entire time but doesn’t ask what I’m doing. She doesn’t point out that I’ve gone over the two minutes I promised her I’d be. When I’m done, I thank her for her time, and she

does something different for once – she puts one hand on my

shoulder and, with the other, grabs my hand and tells me not

to give up hope. I’m not sure whether she means for Bridget or myself.

I already have the car started and in gear when she comes out

the doors and waves me down.

‘It doesn’t mean anything,’ she says, ‘and you need to

understand that. But it’s still something you should see.’

‘What is it?’

‘Come with me,’ she says, and I kill the engine and follow her back inside and upstairs.

My wife is still sitting by the window, staring out at the rain.

Carol stays in the doorway as I walk into the room. Bridget is in the exact same position as earlier, and at first I’m not so sure what it is that Carol wants me to see, but then I see it. Bridget is clutching a photograph of our daughter. At some point since I walked out of here she has stood up and made her way over to the bedside drawers and picked up the photo frame. I think about the photographs of the dead girls in my pocket, and it seems like an omen: that of all days for her to have somehow taken this

photograph it has to be this day. She is holding it against her, the frame pressing into her breasts, the image of Emily facing the window as though Bridget is trying to share the view. I want to read more into it, I want to believe this is more than just one of her automated responses, and I study her face for something – a tear, a flicker of emotion – but there is nothing. Still, it is the first time she has ever picked something up and brought it back to her chair. At least it’s the first time I know of– it could be she does this at night and puts the pictures back in the morning. I don’t know, but I like the idea that in the dead hours of the night she gets out of bed and reaches for Emily. It’s sad, it’s depressing, but it’s the sort of hook that I can come along and hang some hope onto.

I sit down next to her and I rest my head on her shoulder, and I hug her and tears slide from my eyes and soak into her gown, and I pray to the God I want to believe in but can’t that Bridget will tell me that things are okay, that she will stroke the back of my head and comfort me.

But she doesn’t. When I look back at her face it’s just as it was moments before. But my hope stays firmly on the hook I placed

it on. I stay with her for a while – I’m not sure how long exactly, an hour, maybe two. At some point Carol Hamilton walks away.

I see her on my way back out and she smiles but she doesn’t say anything. I guess she is too frightened to offer me hope that she doesn’t think is there.

When I get back outside it’s raining hard. I drive home and

change into some fresh clothes, even ironing a shirt and a pair of pants pulled from the dryer. My look could be the difference between getting the information I need and getting busted.

Back in town I can’t find a park and have to settle for one

six blocks away from the bank. A few years ago and this place

would have been closed on a Saturday afternoon; now hardly

anything closes. I look at my watch and check the opening hours on the door. The bank shuts in less than twenty minutes. I’ve

timed things perfectly.

The security guard gives me a strange look, and I realise it’s because I’ve taken two steps inside and come to a complete stop.

I walk over to him. He seems unsure what to do. I pull out my ID

which I haven’t used in more than two and a half years. I used to have a badge that went along with it, but that got handed back.

The ID has the word Void’ stamped across the side of it, but

I cover it with my finger and let the guard look at it for about a second before I put it away.

‘I seen you on TV,’ he says. ‘Didn’t realise you were still a

cop.’

‘Technically I’m not, but I’m working for them. That’s why

I still have the ID,’ I say, hoping it makes some kind of sense.

‘Didn’t know there was a “technically” when it comes to

working for the police.’

I give him the ‘what-are-you-gonna-do’ stare. ‘Nothing is how

it should be these days,’ I say. ‘All I know is the pay is better on this side of “technically” than on the other side of “actually”.’

He shrugs, as if he doesn’t seem to care one way or the other.

I guess he doesn’t. At twelve bucks an hour, why would he?

have a court order to access a customer’s account,’ I say. ‘Can you point me in the direction of somebody to talk to?’

‘Sure,’ he says, and he brushes a hand over the side of his head where a corner flap of his toupee is sticking up. He leads me

to an open office door and knocks on it. A woman in her mid

thirties stands up from behind her desk and comes over. ‘There’s a guy here who wants to access an account,’ he says, and she looks at him a little blankly because accessing accounts is what people come here to do. But then he adds, ‘He has a court order.’

‘Oh. Well,it’s a little more complicated than that,’ she says, looking me up and down. ‘Hey, haven’t I seen you on TV?’

‘Probably Can we talk in here?’

‘Of course,’ she says, and she looks at the security guard with a dismissive gesture. He doesn’t seem to react one way or the other, he just walks away, but when he gets near the door he seems to look a little more vigilant now that an ex-law enforcement officer is around.

She closes her office door and sits behind her desk. There’s

a name plaque on the front of it. Erica. On the wall there’s an aerial shot of Christchurch that doesn’t show the true emotion of the city, and a couple of photographs, one of which shows Erica standing next to a man who looks vaguely familiar, probably

somebody from one of the numerous banking ads on TV

‘So, what’s this all about, Detective …’

‘Tate,’ I say, and I don’t bother to correct her assumption that I’m still with the force. The business card I was going to give her stays in my hand, and the chances of coming out of here with

what I want have just increased.

“I have an account number here,’ I say, and I slide the bank

statement over to her. I have underlined the account number I

want from Father Julian’s account. I also slide her over the court order. The judge’s name on the top of it is as made up as his

signature.

The thing with court orders is a lot can come down to the

timing of the delivery. Erica picks it up, and then she does exactly what I expect her to do – she glances at her watch. I’ve seen it a dozen times at the end of the working day when we’ve shown

up with one of these orders: it was often the time we’d aim for.

The other thing is that people don’t know what to do with them.

They look at them but they don’t know how to react because

most people have never seen one before. They’ve seen them get

delivered on TV and they figure that what happens on TV is

probably the thing that happens in real life. They suddenly feel like the order has just taken away all their rights of refusal and they don’t argue it. They only ever fight it if they have something to hide.

Erica reads it thoroughly. In the location area the words printed are ‘to access any and all available accounts of the account holder’ and after that I’ve typed out the account number.

‘This is one of your bank account numbers, isn’t it?’ I ask.

‘It is. Is this part of a criminal investigation?’

‘I’m not at liberty to say,’ I say, and I figure she wasn’t expecting anything less.

“I need to call my boss about the order.’

‘No problem.’

“I’ll probably need to fax it to him.’

“I don’t mind waiting. There’s also a space down the bottom

you need to sign once you’ve gone over it.’

She checks the time again. ‘Give me a minute.’

‘Take your time,’ I say.

She leaves me in her office, and I’m not sure whether it’ll be her or the police who come back in. I keep glancing at my watch, and each time I think I should just get up and go, cut my losses before Landry or Schroder arrives.

‘The account is in the name of John Paul,’ she says when she

returns. I figure the court order got faxed to her boss and not much further. Maybe to their law firm, but it’s probably the kind of firm that charges too much to be on retainer on the weekend, so it’s sitting in a fax tray somewhere. I’ve seen it dozens of times.

She’s not giving me a lot, just a few details. She doesn’t see how it can hurt. She sits back down behind her desk. ‘Like the Pope,’

she adds.

‘How long has it been active?’

She twists the computer monitor to face her. ‘Twenty-four

years.’

“I need printouts of payments.’

‘Okay. It’ll take a few minutes.’

“No problem.’

She taps away at her keyboard, then leans back. I don’t hear a printer going anywhere.

‘Did John Paul have any other accounts set up? Or was it just

this one?’ I ask.

‘Just this one. But…’ She stops, then looks back down at the court order.

‘What?’

‘When he set up the account, he also set up a safety deposit

box.’

A safety deposit box? Here?’

‘It’s even at this branch.’

‘Can I access it?’

‘The court order doesn’t say you can.’

‘Listen, Erica, this is very, very important.’

She seems unsure of what to do.

‘This safety deposit box – did John Paul gain access to it with a key?’ I ask.

‘Of course. That’s how everybody opens them.’

‘When was the last time he accessed it?’

She looks at her monitor. ‘Six weeks ago.’

‘How many keys were issued?’

‘Just the one.’

‘Can you tell me if this is it?’ I reach into my pocket and drag out my keys. I twist the one Bruce Alderman gave me off the ring and hand it over to her.

‘Sure. This is for one of our boxes, though I can’t tell you if it’s specifically for John Paul’s box. We don’t label the keys for a reason, you know, in case they get lost and people try to use them.’

I stand up. ‘I need you to take me to it.’

‘What?’ She looks at her watch again. ‘I don’t know – I’ll

have to check with my boss.’

‘Okay, do what you need to do. But you essentially just said

that whoever has the key can gain access to the box, that’s why you don’t label them. If you want, though, I can get the court order amended – that’s fine too. I can get the judge to sign it and be back here in —’ I glance at my watch – ‘an hour and a half.

Two hours tops.’

‘Two hours?’

‘Yeah. That’s what’ll it take.’

She gives it only a few seconds’ thought. ‘Okay. Since you

have the key I don’t see any problem. The room is this way’

And she picks up the key, and I follow her out of her office.

chapter forty-eight

Most of the safety deposit boxes are a little bigger than a

phonebook, but there are perhaps a dozen or so that are two

to three times bigger. There are three walls full of them, each numbered. Erica approaches them slowly, still reluctant to be

doing this, but then she looks at her watch and remembers that it’s time to leave and Saturday night is waiting. She puts the key into one of the bigger ones, twists it, opens the door and pulls out a metal tray from within. She sits it down on the table, then points out three small rooms off to the side.

‘There’s privacy in there. Take your time,’ she says, sounding as if she doesn’t want me to take my time but to get in and out of there in under a minute. I intend to help her out there.

The room doesn’t have much legroom. I can reach out and

touch both walls at the same time without stretching. I put the tray on the table and open it.

Audio tapes are stacked side to side, the small microcassette

ones that take up less room. They are all labelled with numbers. I pull a large plastic evidence bag out of my pocket and start filling it up. There is also an accountant’s notebook, and I flick it open to see bunches of names and dates and figures before I throw that into the evidence bag as well. I step out of the cubicle and find Erica is back. She looks at the evidence bag but says nothing.

I’ve closed over the seal and signed it so it all looks more official.

I ask her to sign it too and she does, but she has to hand me the cardboard box she has filled with the printed bank statements

first.

She walks with me to the front door. The security guard is

waiting for me. “I always wanted to be a cop,’ he says. ‘Would’ve done it too, but I have a banged up knee that stopped me.’ it’s a story heard from plenty of security guards over the years. It might have been a banged up knee, or it could have been their or lack of motivation, or he failed the psych test.

The bank is almost empty now. The security cameras in the

ceiling have captured my image from a dozen different angles and I know this is going to come back and really bite me in the arse.

But that’s for another day. Maybe the same day they dig Sidney Alderman up. And today things are going well. Today my wife

hugged a photo of my daughter and I hit a lead that could take me straight to Rachel’s killer. When you get those kinds of leads, you don’t slow down for anything.

As the guard unlocks the door to let me out, Erica starts to

turn away.

‘Just one more thing,’ I ask her, and she turns back. She seems about to glance at her watch again but pulls herself out of the movement. ‘The photograph behind your desk, there’s you and

another guy – he looks around fifty, maybe sixty. He seems

familiar.’

‘He was the bank manager here for many years,’ she says. ‘You

would have seen him around if you ever came in here.’

‘Was?’ I ask, and I’m starting to figure out who it is.

‘Henry died a couple of years ago,’ she says.

‘Henry Martins.’

‘That’s right. You knew him?’

“I went swimming with him once.’

Outside, the rain is still thick and heavy, and so is the traffic.

I pass a guy scraping chewing gum off the footpaths and depositing his collections into a plastic bucket. He’s wearing a T-shirt that has a picture of the Easter Bunny up on a crucifix. It says Jesus had a stunt double, and I wonder how Father Julian would have reacted to seeing it. Another guy sniffing glue is leaning up against a bike rack watching the guy. I guess Saturday brings the crazies out a little earlier.

I get past them and run through the rain to my car.