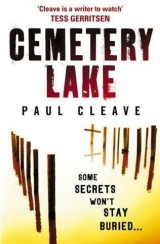

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter fifty-one

‘I know who you are.’The voice sounds a little familiar but I can’t place it.

‘Do you have something to confess?’

‘You killed her, you know.’

‘What are you talking about?’Father Julian’s voice has a rushed quality, as if he has just entered the confessional after running from the rectory.

‘As if you strangled her yourself. What you do in life has

consequences, wouldn’t you say, Father?’

‘Yes, of course, but what you’re talking about doesn’t make

sense.’

‘All our actions have consequences, don’t they, Father. For all of us.’

‘We need to be aware and responsible for our actions, yes, that’s true.’

‘Even you, Father?’

‘Do you have something to say?’

‘Are there others?’

‘Others? I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘Other children. Like me. Are there others like me.’

We’re all children of God, no matter what our actions.’

‘I’m not talking about God.’

‘I don’t understand.’

‘I’m talking about you, Father Julian. I’m talking about your

children. Are there more of us?’

‘Oh my God.’

‘See, you do understand. Your actions have consequences, Father.

Or should I say Dad?’

‘I… I don’t know who you are.’

‘Would you like to know?’

‘Of course.’

‘I’m the man who just killed your daughter, Father. Her name

was Rachel Tyler. She died slowly, Dad. She was my sister, and she died slowly.’

‘Jesus,’ Father Julian says, the word coming out in a whisper, and I can hear the pain in his voice. I know that pain. I think I even said the same thing when I picked up the phone to learn

Emily was dead and my wife gone for ever.

‘I told her about you. She never knew her dad, but in the

moments before she died I told her. She knew everything she wanted to know and then more than she could handle. Do you think that knowledge comforted her?’

‘I… I…’

‘You what, Father? You don’t know? You don’t know what to

say? How do you think I felt, finding out who I was? How do you think it felt being abandoned?’

‘Please, please, don’t…’

‘Don’t what? You don’t even know what to do, do you, Father?

You feel helpless. Do you suddenly feel as though God has abandoned you? I know all about abandonment. You feel helpless and that’s exactly how Rachel felt in those last moments. Tell me, Father, do you still want to do something good for her?’

Father Julian doesn’t answer. I can hear his breathing. It sounds louder than it ought to be on a tape recorder with such a small speaker. The vocals are tinny, but that breathing is deep, like a wounded whale.

‘You can’t kill her,’ he says at last, but it’s such a ludicrous thing to say to a man who has already committed the act. ‘Please, please, tell me this is wrong.’

‘Bury her,’the. killer says.

‘What?’

‘I’mgiving you a chance, Dad. You can bury her and you can

pray over her. You can visit her as often as you want – something you never did while she was alive.’

‘This is madness,‘“Father Julian says.

‘ What other choice do you have? I have kept her for you to bury.

She is here, at your church. You cannot go to the police, because you can’t afford your parish to know she was your daughter. Or that you have others.’

‘Ihave no other children.’

‘You have me. All you can do now is bury her and pray and

maybe we’ll talk about it next time.’

‘Next time?’

But the man doesn’t answer. The confessional door opens

then closes. Father Julian cries out for the man to wait: there are footsteps, then nothing. A few seconds later the tape goes quiet, and ten seconds after that a new voice comes through the speaker, confessing to an attraction to somebody who isn’t his wife.

I rewind the tape and listen through it again. The words of

Rachel’s killer are chilling and form knots in my stomach. Hearing them again is almost enough to take me there, to be inside that confessional booth. I wonder where Rachel’s body was left,

whether she was placed on a pew or dumped on the doorstep.

I picture Father Julian cradling her, part of him wanting to call the police, a greater part not wanting his secrets exposed. He was a coward who could not betray the confessional, a coward who

asked Bruce, his son, to bury the girls and to bury the truth.

I check the log and find the date the second girl went missing.

I start forwarding through the corresponding tape, going through snippets of dialogue until I hear the same voice. I rewind it a bit and find the beginning of the conversation.

‘You lied to me, Father.’

‘I lied to you how, my son ?’

‘My son? That’s very accurate, isn’t it.’

‘Oh my God.’

I pause the tape and check the time stamp against the log.

This time Father Julian has written down Luke Matthews. Last

time it was Paul Peters. I check off the rest of the dates and find more names that stick out: John Philips and Matthew Simons.

Four names that are mixtures of names of the Apostles. Father

Julian never wrote down his son’s real name. Did he not know

it? Was it a son he paid child support to? Or one he completely abandoned?

‘I knew there were others. And now Julie is the second.’

‘What have you done?”Father Julian asks. ‘Did you know her?’

‘What have you done?’Father Julian repeats. ‘You probably never saw her, did you.’

‘No.’

‘Then thank me. You can give her the same burial you gave her

sister. My sister.’

Father Julian starts to cry. His sobs through the tape are the hardest things I’ve ever had to listen to.

I press pause and go into the kitchen. I make some coffee.

Suddenly I don’t want to go back into my office. I don’t want

to listen to the rest of the conversation. I just want to burn the tapes and drive to the nearest bottle store and immerse myself in the bourbon that has kept me so numb for the last month. Father Julian’s sobs have brought tears to my eyes. I close them and the tears break away and run down the sides of my face. I am almost with him as he listens. I know how he feels hearing for the first time his daughter is dead. I went through it once. He has gone through it twice. Did he go through it more than twice? I think he did. I think he went through it four times. Did it get easier or harder? Did it age him, did it break him, did it make him

deny his God, or make his faith stronger? He could not break the confessional vow. Even when there was a pattern and he knew

what was happening, he did not break it. He could break it to

blackmail adulterers, but not to save his children. What twisted morals Father Julian had, but then churches are full of people preaching one thing and practising another. Every day he must

have struggled with the man he was. Perhaps he didn’t want to

struggle any more. He hadn’t been to his safety deposit box in the four weeks before he died. He knew the key was missing, and maybe he knew Bruce took it. Maybe he even figured out that it had been given to me. I think he knew that in some way this was coming to an end.

I don’t touch the coffee. I leave it on the bench and walk back to the office.

‘You can pray over them, Father. You can pray at the same

time.’

‘How did you know she was your sister?’

‘Perhaps God can tell you.’

The confession ends. I find the third one, and match the time

stamp to John Philips.

‘Why are you doing this?’ Father Julian asks as his son tells him he has met another of his sisters. ‘What did they do to you?’

‘It’s what they could have done.’

‘Why any of this? Why come here and tell me?’

‘Because you’re the only family I have.’

I keep listening. The dialogue is similar to the others. Father Julian’s sobs are just as loud. A name comes up. Jessica Shanks.

She was the third girl to have gone missing and the oldest. She was the one Father Julian started paying for in the beginning, five years before Rachel was born.

I stop the tape and find the last confession.

They are all dead now, Father.’

‘I don’t want you coming back here.’

‘All of the sisters. You can see them whenever you like. Do you now finally take the time to visit them?’

‘I want you to leave.’

‘Am I right?’

‘What?’

There are no more, are there.’

‘No.’

‘Ifyou’re lying to me, Father, I will find out.’

‘I know.’

‘And I won’t be happy.’

‘I’m not lying.’

‘If you are lying, Father, I will do two things. I will find the girls and I will kill them. I will make them suffer. Do you want to know what the second thing is?’

‘No.’

‘I will come back here, Dad, and I’ll cut out your tongue so you can never lie to me ever again.’

chapter fifty-two

It’s about as official as it can get. The dead girls are Father Julian’s daughters. Their killer is Father Julian’s son. I look down at the photographs of Jeremy and Simon and Bruce. Then I look at

the photograph of the fifth girl, Deborah. Could be she is dead already, dead and buried and never found, or it could be she is living in another city in another part of the world, oceans and landscapes away from all of this.

Father Julian’s logs show who he was recording and

blackmailing, but they don’t show how many children he had.

The bank statements don’t show that either. There aren’t any

Aldermans in these statements for a start. There isn’t enough

information to know how many women Father Julian used his

position to take advantage of.

There are seven names on the bank statements. Four of them

belong to the families of the dead girls. Of the three left, two might be for Simon and Jeremy, and one might be for Deborah,

or it could be for different children I don’t know about. All I can do is hope the photographs match up with the bank statements.

I have three first names – Jeremy, Simon and Deborah – and

three last names from the bank statements. I grab a phonebook

and start matching the names up, hoping for a hit, and the first one comes when I end up speaking to Mrs Leigh Carmel. I

identify myself and she quickly asks what it’s about, and there is a hesitancy in her voice that suggests she thinks I’m about to try and sell her something. I tell her I’m trying to track down her son, figuring I have a two-to-one chance it’s a son rather than a daughter, and I’m correct.

‘What’s he done now?’ she asks.

‘I just need to talk to him. It’s important.’

“He’s always done something,’ she says. ‘That’s always been

the problem with Jeremy. Why don’t you speak to his probation

officer? They seem to have a closer relationship than we’ve ever had.’

She gives me the number, and I hang up and call the probation

officer straight away.

‘You know that ain’t the kind of information I can give out

over the phone,’ he says. “Not to a private investigator.’

“How about I give you my number and he can call me?’

‘We’re not in this business to forward on messages.’

‘Okay, okay, let me think a minute. Right, can you tell me

where he was two years ago? Was he in jail?’

‘Two years ago? Yeah. He was in jail then. He’s been in for a

four-year stretch. Got let out two months ago.’

‘What’d he do?’

‘It’s public record,’ he says. ‘Look it up.’

I thank him for his time and cross Jeremy Carmel off my list.

It leaves me with two first names and two last names that could match up either way.

My next hit comes a few calls later, when a woman answers the

phone and I ask for Simon.

‘Who?’

‘Sorry, I mean Deborah. I’m trying to get hold of her.’

‘Well, so are we. We haven’t seen her since yesterday. Can I ask who’s calling?’

Her words make me tighten my grip on the phone. I tell her

who I am and that I’m a private investigator.

‘Investigating what?’ she asks. ‘Has something happened to

Deborah? Is she in trouble? Is that why we haven’t heard from

her?’

“No,it’s nothing like that.’

‘Then what?’

‘I just need to get hold of her. It’s important.’

‘I don’t like the way you sound,’ she says, and I realise my grip is so tight on the phone my knuckles have turned white. ‘You

make it sound like she’s in danger.’

I decide to go with the truth. ‘She might be. Please, you have to help me out here, I need to …’

‘What kind of danger? Tell me! What’s happened to my

daughter?’

I ignore her question and push on. It’s the only way, otherwise I could end up spending two hours on the phone with her. ‘Do

you know if she was seeing anybody?’

‘Is this some kind of joke? Has somebody put you up to this?

I’m calling the police.’

‘Wait, wait just a second. Does Deborah know who her real

father is?’

The woman says nothing, and I don’t jab her with another

question, just ride the silence out, knowing her shock at the

question may turn to anger or denial.

‘Who are you?’

‘I’ve already told you,’ I answer.

‘What is it you’re trying to ask? Tell me.’

‘Is her real father Stewart Julian?’

Again a pause. ‘Where’s my daughter? What aren’t you telling

me?’

‘Please, is Father Julian Deborah’s real father?’

“How is this important?’

‘It’s important because it will help me find Deborah.’

‘I’m phoning the police.’

‘Good, I want you to, but first tell me. Father Julian was

murdered because he was protecting secrets. They were his own

secrets. Was he Deborah’s father?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did he have any other children?’

‘Other children? I… I guess I’ve never really thought about it.

I suppose it’s possible, just like anything is possible. But I doubt it.’

‘Okay, I’m going to look for Deborah. I want you to call the

police and tell them she’s missing. But first I want you to tell me where she lives and give me her number.’

I write the details down, and try calling Deborah immediately

after I’ve hung up. She doesn’t answer. I leave a message.

That leaves me with Simon Nichols. He is the last person in

the photos, the last person to be paid for in the bank statements, and the odds are that makes him the killer.

There are a few people with that name and initials in the

phone book. I ring them all but get nowhere. In the end I’m able to track down his mother, who answers on the tenth ring, just

before I hang up.

‘I’m trying to get hold of Simon,’ I say.

‘Simon?’ she says. “Erm, can I ask who’s calling?’

‘My name is Theodore Tate. I’m a private investigator.’

‘What is this about?’

‘I just have a few questions for him, just some routine stuff

that might really help me out on a case.’

She doesn’t answer at first, then there are some soft sounds

and I get the idea she is crying.

‘You’re about a year too late,’ she says, and suddenly I know what’s coming up. Suddenly I know she’s about to tell me that her son was murdered.

‘It was about a year ago,’ she says, after telling me Simon was stabbed to death in his own home. ‘The police haven’t caught the guy, not…’ She can’t finish.

Her sobs remind me of how Julian sounded when he was

listening to the confessions of his daughters’ killer. I hear her cries, but all I can do is think about how empty my suspect pool is, and I now have absolutely no idea how to find the other brother who has killed so many.

chapter fifty-three

I stare at the photographs of the girls as if somehow they’re going to rearrange themselves and reveal an answer. I look at Simon, dead now, one more unsolved murder in a city with dozens of

murders. The killer’s signature is different for his sisters and brother. I wonder whether he’d have killed Jeremy too, whether the desire is there, or whether he even knows of the other brother.

He certainly knew about Bruce. What relationship did they have for Bruce to be safe? Bruce’s last words about dignity echo in my thoughts, making me shiver. Between Bruce and Father Julian,

they thought they were giving the girls some dignity, a burial place where they could be prayed over and looked after. But what of those they took from the coffins and discarded into the water?

What of their dignity?

I keep starting to reach for something different, to move it

from one place to another, to shift about the bank statements and the logs, hoping, hoping … but there is nothing. I look at my watch. Saturday is shifting along quickly. And Deborah Lovatt

is in danger.

I head back out to the car. The mud I splashed through it last night has dried. Dad would have a heart attack if he saw it. I dial the cellphone and try for Schroder but he doesn’t answer. I hang up and dial back and get the same result. I leave a message, then decide to call Landry.

‘Jesus, Tate, you just don’t know when to let go.’

‘I might have something for you.’

‘Really? I have something for you. You left your jacket and

shoes at the church last night.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Good one, Tate, but you know what? I’m not even going to

get into it. We both know you were there and we both know that I can’t prove it. So how about you do me a favour and stay the hell away from me.’

‘Look, Landry, this is important, okay? Real important. Did

you find a tape recorder at the church?’

A tape recorder? What the hell are you on about?’

‘Did you find one or not?’

“No, there was no tape recorder.’

‘Okay. I can help you find who killed those girls.’

‘I’m listening,’ he says.

‘Where are you?’

‘What does it matter?’

‘I need you to go to the church.’

‘Why?’

‘Because you missed something.’

‘Missed what? This tape recorder?’

‘I’ll tell you when you get there.’

‘Come on, Tate, stop fucking around. It’s too damn late for

your bullshit. I’m tired.’

‘Just call me back when you get there, okay?’

I hang up on him before he can reply.

I drive to Deborah Lovatt’s house, and can tell immediately

that nobody is home. Her mother said she lived with two

flatmates. If they’re around the same age as Deborah, then they’ll be out in town drinking or at the movies somewhere. I get out of the car and walk around, but nothing stands out as being wrong.

No busted doors. No broken windows. I leave a card wedged in

the door so it hangs over the keyhole. I leave a note on the back saying it’s urgent I speak to Deborah. Deborah’s mother will

have called the police, but the way things work in this city, that doesn’t mean help is coming soon.

Traffic is thick on the way back to town, full of people all

looking for somewhere better to be. Queued up at the lights,

I can hear the stereo in the car behind me, the thump thump

thump making the chassis of my car vibrate. I can see movement in my rear-view mirror – occupants of the car are treating the ride into town as a party.

My cellphone rings and I answer it. The music from the

other car drowns out Landry’s voice. I push my cellphone harder against my ear.

‘… do now?’

‘What?’ I ask.

The light turns green. The guy behind me toots his horn

even though it’s been less than a second. I move through the

intersection and pull over. There’s a guy dressed like Jesus sitting on the side of the road. He’s biting into an egg carton. He looks up at me, his bloodshot eyes locking onto mine, and I realise he’s at the end of the road I’ll be driving along if I decide that maybe the drinking is for me after all.

‘You there, Tate?’

‘Give me a second.’

There are toots and yells and waves as the car behind me

passes. I pull away from the kerb and drive further up the road to find another park away from egg-carton guy.

‘Okay, go ahead.’

‘You’re really testing my patience, Tate. I’m at the church, so what do I do now?’

‘Head down to the confessional booths.’

‘Why?’

‘Just do it.’

‘Okay, okay. You know it sounds like you’re driving?’

‘Well, I’m not.’

‘Yeah. Okay, I’m at the booths. Now what?’

‘Open them up.’

‘What am I looking for?’

‘Check Father Julian’s side. Check the roof. The back wall.

Just check all of it.’

‘Check it for what? This tape recorder you’re telling me about?

You think Father Julian was making secret recordings?’

‘Just do it.’

‘There’s nothing in here.’

‘Yes there is. Tap the wall or something.’

‘Tap it? You think there’s a false panel?’

‘Yeah I do.’

He starts tapping the walls. The small knocks carry through

his cellphone. ‘This is a goddamn waste of…’

He doesn’t follow it up, and I know what he’s found.

‘How the hell do you know about this?’ he asks.

‘Father Julian was recording the confessions. He was

blackmailing people.’ I look in the mirror and see egg-carton guy walking towards me. The mirror makes him appear closer than

he actually is. ‘Since you hadn’t found it already, I reasoned the tape recorder was hidden. What better place to hide it?’

‘That’s why you were following him? Fuck, Tate, why couldn’t

you have told us? You sure as hell could have saved us a lot of work and a lot of pain. And finding out this way, man – it

doesn’t look good. It looks like you put it there when you broke in last night.’

‘I didn’t break in. All I knew was the tape recorder had to

be there somewhere, and anyway, I only just found out. Look,

Julian recorded his killer, right? He knows who killed those girls.

Is there a tape in the machine?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Then listen to it. Could be the night Father Julian died, he

took a confession first. It could be the last voice you hear on that tape is his killer.’

‘You need to come down to the station, Tate.’

Egg-carton guy stretches out the bottom of his shirt and

starts using it to wipe down the side window. He moves it in

circular motions, but it isn’t the kind of detailing my dad would have in mind. I roll the window an inch and hand him a couple

of dollars. He says something but I don’t quite hear him, then he wanders away.

‘Tate? You still with me?’ Landry asks.

‘Play the tape.’

‘I’ll play the tape when I’m done with you.’

‘Maybe Julian referred to him by name.’ I say. ‘Maybe he did

that because he knew what might be coming up.’

‘I’m sending somebody to pick you up.’

‘I’m not even home.’

‘How can that be? You’ve lost your licence. You out

walking?’

‘Besides, you’ve got something more important to take care

of.’

‘Yeah? You got somewhere else for me to go?’

‘There’s another girl.’

‘Oh Jesus, what is it with you? Everywhere you go people are

showing up dead, or never showing up again.’

‘She may not be dead. But you need to find her.’

‘Tell me.’

I lay it out for him. Not all of it, but most of it. And not all of it truthfully. I tell him about the photographs of Father Julian’s children, telling him Bruce gave them to me but that I only just figured out the connection. I tell him how four of the girls are dead and there is still one out there. I tell him about the key Bruce left for me, and the tapes that I found, along with the log.

‘You have got to be kidding me,’ he says. ‘You know you’re

in for a world of shit now, right? Going into that bank like that?

You should have just called me.’

‘There wasn’t time, and like I said, I had a key’ I say, not

mentioning the court order. That will come later.

‘You’ve been holding out on me for the last month, slowing

down my investigation, and you’re telling me there wasn’t

time?’

‘Hey,it’s not my fault I’m ahead of you. And you should

be thanking me. Most of what you have is because of me. If

anything, I’ve sped up your investigation.’

‘Fuck you, Tate. DNA would have told us those girls were

related. We’d have figured out the rest.’

‘Yeah, maybe you would have, maybe not, but you wouldn’t

even be looking yet. Not until those results came in.’

‘I’m coming to your house. Now. I want you to be there,

okay? I’m coming to get all this stuff. And we’re going to have a nice long chat, just the two of us.’

He hangs up before I can debate the issue.

I drive back home and have barely gone inside when Landry

pulls up. He looks furious. He has an edge to him that makes me wonder how many times he’s looked into the abyss.

‘Where are they?’ he asks. ‘The tapes?’

‘You first. You listen to the one you found in the

confessional?’

‘Yeah. I did. There’s nothing on it of any use. Fact is, none of these tapes are going to be any good. You know we can’t use them.

Even if it was us who found them. Can you imagine the kind of

shit storm we’ll have if the public ever finds out about them?

There are going to be lots of confessions of people cheating on their husbands and wives, cheating with their taxes, cheating in all the possible ways the human race can cheat. There’ll be more too. Who the hell knows whether the sanctity of the confessional extends to a tape recording? Or is it limited only to the priest?’

‘So you’re going to keep them quiet.’

‘We’ll listen to them, that’s for sure, but I don’t imagine we’re going to be making any arrests from them. And if our killer is on these tapes …’

‘He is.’

‘… then we gotta find a way of working around it. We

mention these things and we’re handing him a defence.’

I lead him into my office and hand him over the log.

‘Money comes in from blackmailing,’ he says, ‘and money

goes out for the kids. Looks like our Father Julian was a busy man. It’s probably a miracle he lasted as long as he did without anybody finding out.’

‘Miracles are in his line of work.’

‘Maybe not in the end.’

‘I think Henry Martins knew’

‘What?’

I fill in the Martins connection. He absorbs it, but like me he doesn’t know what to make of it.

‘His body was too decomposed from the water,’ he says.

‘There was no way to get any toxicology from him. No way to

tell if he was murdered.’

‘What about the new husband? The one who started all of

this?’

‘Who?’

‘The one who died and made you want to dig up Henry

Martins.’

He starts to pile the tapes into the evidence bag. “His death

was accidental. Turns out he was being exposed to some toxin

through his job that he shouldn’t have been exposed to. I don’t know, it wasn’t my case. Lead paint or something. It was fairly prolonged. Weird how it’s all led to this.’

“It’s getting close to eleven o’clock, and suddenly I feel

exhausted. All I want to do is get Landry out of my house so I can go to bed.

‘Was this his? It looks new,’ he says, picking up the small tape recorder.

“I just bought it today. I have a receipt.’

‘Yeah, well, I’m taking it. Consider it your first step in

cooperating with the police. Enough of those small steps might go a long way to helping you out, Tate. What we got now – and I don’t mean the drunk driving charges. We’ve got breaking and entering …’

‘No you don’t.’

‘We’ve got interfering with a criminal investigation. We’ve

got…’

‘Look, I get the point, okay?’

He picks up the photographs. ‘This them?’

Yeah.’

He says nothing for a few seconds, and then, “I really should

be taking you in.’

‘Look, Landry, I’m about to crash here, okay? I’m beat. And

I’ve told you everything I know, and I’ve given you everything I have. Go and do you’re job and figure out who this maniac is before he kills Deborah Lovatt.’

‘The fifth girl.’

‘Yeah. The fifth girl’

‘Okay, Tate. For once I believe you. But I still gotta take you in.’

‘Look, if you take me in, then what? You’re going to want

to listen to all those tapes first, and you’re going to want to run down everything I’ve told you about. So all you’re going to do is sit me in an interrogation room for twelve hours before you even speak to me. It’s pointless. Let me stay here, let me get some sleep, and if you want me tomorrow you’ll know where to

find me.’

He doesn’t answer, but he slowly nods.

I walk to the front door with him, and as angry as he is at me I’m pretty sure that if he’d been the one two years ago to decide not to exhume Henry Martins, then he’d be the one now needing

to find justice for those dead girls.

I listen to him drive off.

My head hits the pillow, and I think I might even have slept

for about two minutes before my cellphone rings.

‘Why do I feel like I’ve just been played?’ Landry asks.

I don’t answer him.

He carries on. “I pressed play on that tape recorder of yours to get a preview of what was to come.’

And?’

‘And what? It was up to Sidney Alderman. He was confessing

about killing his wife. I guess that’s the one you wanted me to hear first, and it means you knew I was going to take your tape recorder. You knew I’d listen to it. Why?’ he asks.

‘Makes you wonder what he was capable of, right? Guy like

that, makes you wonder.’

‘Good night, Tate.’

‘Good night, Landry’

I hang up and turn off my cellphone, satisfied that the police no longer have any reason to dig Mrs Alderman out of the

ground.