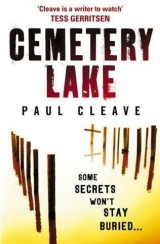

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Cemetery lake

by

PAUL CLEAVE

What began as a routine exhumation of a suspected murder victim quickly turns complicated for private investigator Theodore Tate…Theo Tate is barely coping with life since his world was turned upside down two years ago. As he stands in the cold and rainy cemetery, overseeing the exhumation, the lake opposite the graveyard begins to release its grip on the murky past. When doubts are raised about the true identity of the body found in the coffin, the case takes an even more sinister turn. Tate knows he should walk away and let his former colleagues in the police deal with it, but against his better judgement he takes matters into his own hands. With time running out and a violent killer on the loose, will Tate manage to stay one step ahead of the police? Or will the secrets he has buried so deeply be unearthed?

Also by Paul Cleave

The Cleaner

The Killing Hour

S

Published by Arrow Books 2009

13579 10 8642

Copyright S Paul Cleave, 2008

Paul Cleave has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

First published in New Zealand in 2008 by

Black Swan, an imprint of Random House New Zealand

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

Arrow Books

The Random House Group Limited

20 VauxhaU Bridge Road, London, SW1V 2SA

www.rbooks.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/omces.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A ZIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099536253

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our tides that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo.

Our paper procurement policy can be found at

www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI Cox & Wyman, Reading, RG1 8EX

6 pounds 99 pence

To Joe – who got the ball rolling

chapter one

Blue fingernails.

They’re what have me out here, standing in the cold wind,

shivering. The blue fingernails aren’t mine but attached to

somebody else – some dead guy I’ve never met before. The

Christchurch sun that was burning my skin earlier this afternoon has gone. It’s the sort of inconsistent weather I’m used to. An hour ago I was sweating. An hour ago I wanted to take the day

off and head down to the beach. Now I’m glad I didn’t. My own

fingernails are probably turning blue, but I don’t dare look.

I’m here because of a dead guy. Not the one in the ground

in front of me, but one still down at the morgue. He’s acting

as casual as a guy can whose body has been snipped open and

stitched back together like a rag doll. Casual for a guy who died from arsenic poisoning.

I tighten my coat but it doesn’t help against the cold wind.

I should have worn more clothes. Should have looked at the

bright sun an hour ago and figured where the day was heading.

The cemetery lawn is long in some places, especially around

the trees where the lawnmower doesn’t hit, and it ripples out

from me in all directions as though I’m the epicentre of a storm.

In other places where foot traffic is heavy it’s short and brown where the sun has burned all the moisture away. The nearby

trees are thick oaks that creak loudly and drop acorns around the gravestones. They hit the cement markers, sounding like bones of the dead tapping out an SOS. The air is cold and clammy like a morgue.

I see the first drops of rain on the windscreen of the digger

before I feel them on my face. I turn my eyes to the horizon where gravestones covered in mould roll into the distance towards the city, death tallying up and heading into town. The wind picks up, the leaves of the oaks rustle as the branches let go of more acorns, and I flinch as one hits me in the neck. I reach up and grab it from my collar.

The digger engine revs loudly as the driver, an overweight

guy whose frame bulges at the door, moves into place. He looks about as excited to be here as I am. He is pushing and pulling at an assortment of levers, his face rigid with concentration. The engine hiccups as he positions the digger next to the gravesite, then shudders and strains as the scoop bites into the hardened earth. It changes position, coming up and under, and filling with dirt. The cabin rotates and the dirt is piled onto a nearby tarpaulin.

The cemetery caretaker is watching closely. He’s a young guy

struggling to light a cigarette against the strengthening wind, his hands shaking almost as much as his shoulders. The digger drops two more piles of dirt before the caretaker tucks the cigarettes back into his pocket, giving up. He gives me a look I can’t quite identify, probably because he only manages to make eye contact for a split second before looking away. I’m hoping he doesn’t

come over to complain about evicting somebody from their final resting place, but he doesn’t – just goes back to staring at the hollowed ground.

The vibrations of the digger force their way through my feet

and into my body, making my legs tingle. The tree behind me can feel them too, because it fires more acorns into my neck. I step out of the shade and into the drizzle, nearly twisting my ankle on a few of the ropey roots from the oak that have pushed through the ground. There is a small lake only about fifteen metres away, about the size of an Olympic swimming pool. It’s completely enclosed by the cemetery grounds, fed by an underground stream. It makes this cemetery a popular spot for death, but not for recreation.

Some of the gravesites are close to it, and I wonder if the coffins are affected by moisture. I hope we’re not about to dig up a box full of water.

The driver pauses to wipe his hand across his forehead, as if

operating all of those levers is hot work in these cold conditions.

His glove leaves a greasy mark on his skin. He looks out at the oak trees and areas of lush lawn, the still lake, and he’s probably planning on being buried out here one day. Everybody thinks that when they see this spot. Nice place to be buried. Nice and scenic.

Restful. Like it makes a difference. Like you’re going to know if somebody comes along and chops down all the trees. Still, I guess if you have to be buried somewhere, this place beats out a lot of others I’ve seen.

A second flatbed truck sweeps its way between the gravestones.

It has been pimped out with a wraparound red stripe and fluffy dice in the window, but it hasn’t been cleaned in months and

the rust spots around the edges of the doors and bumper have

been ignored. It pulls up next to the gravesite. A bald guy in grey overalls climbs out from behind the steering wheel and tucks his hands into his pockets and watches the show. A younger guy climbs out the other side and starts playing with his cellphone.

There isn’t much more they can do while the pile of dirt grows higher and higher. I can see the raindrops plinking into the lake, tiny droplets jumping towards the heavens. I make my way over

to its edge. Anything is better than watching the digger doing its job. I can still feel the vibrations. Small pieces of dirt are rolling down the bank of the lake and splashing into the water.

Flax bushes and ferns and a few poplar trees are scattered around the lakeside. Tall reeds stick up near the banks, reaching for the sky. Broken branches and leaves have become waterlogged and

jammed against the bank.

I turn back to the digger when I hear the scoop scrape across

the coffin lid. It sounds like fingers running down a blackboard, and it makes me shiver more than the cold. The caretaker is shaking pretty hard now. He looks cold and pissed off. Until the moment the digger arrived, I thought he was going to chain himself to the gravestone to prevent the uprooting of one of his tenants. He had plenty to say about the moral implications of what we were doing. He acted as though we were digging up the coffin to put him inside.

The digger operator and the two guys from the flatbed pull on

face masks that cover their noses and mouths, then drop into the grave. The overweight guy from the digger moves with the ease

of somebody who has rehearsed this moment over and over. All

three disappear from view, as if they have found a hidden entrance into another world. They spend some time hunched down, apparently figuring out the mechanics to get the chain attached between the coffin and digger. When the chain is secure the driver climbs back into place and the others climb out of the grave. He wipes his forehead again. Raising the dead is sweaty work.

The engine lurches as it takes the weight of the coffin. The

flatbed truck starts up and backs a little closer. With the two machines violently shuddering, more dirt spills from the bank and slides into the water.

About five metres out into the lake, I see some bubbles rising to the surface, then a patch of mud. But there is something else there too. Something dark that looks like an oil patch.

There is a thud as the coffin is lowered onto the back of the

truck. The springs grind downwards from the weight. I can hear the three men talking quickly among themselves, having to nearly shout to be heard over the engines. The cemetery caretaker has disappeared.

The rain is getting heavier. The dark patch rising beneath the water breaks the surface. It looks like a giant black balloon. I’ve seen these giant black balloons before. You hope they’re one thing but they’re always another.

‘Hey, buddy, you might want to take a look at this,’ one of the men calls out.

But I’m too busy looking at something else.

‘Hey? You listening?’ The voice is closer now. ‘We’ve got

something here you need to look at.’

I glance up at the digger operator as he walks over to me. The caretaker is starting to walk over too. Both men look into the water and say nothing.

The black bubble isn’t really a bubble but the back of a jacket.

It hangs in the water, and connected to it is a soccer ball-sized object. It has hair. And before I can answer, another shape bubbles to the surface, and then another, as the lake releases its hold on the past.

chapter two

The case never made the news because it was never a case. It was a slice of life that happens every day, no matter how hard you try to prevent it. It made the back pages where the obituaries are listed, along with the John Smiths of this world who are beloved parents and grandparents and who will be sorely missed. It was a simple story of man-gets-old-and-dies. Read all about it.

It happened two years ago. Some people wake up every

morning and read the obits while downing scrambled eggs and

orange juice, looking for a name that jumps out from their past.

It’s a crazy way to kill a few minutes. It’s like a morbid lottery, seeing whose number has come up, and I don’t know whether

these people find relief when they get to the end and don’t find anybody they know or relief when they do. They’re looking

for a reason; they’re looking for somebody, wanting to make a

connection and to feel their own mortality.

Henry Martins. I pulled those stories from the library

newspaper database this morning just like I did two years ago, and read what people had to say about him when he died, which

wasn’t much. Then again, it’s hard to sum up a person’s life in five lines of six-point text. It’s hard to say how much you’re going to miss them. There were eleven entries for Henry over three

days from family and friends. Nobody made my job easier by

throwing a ‘glad you’re dead’ in with their woeful sorrows, but each obituary read like the others: boring, emotionless. At least that’s the way they come across when you don’t know the guy.

Henry Martins’ daughter came into the station a week after

the old man was buried. She sat down in my office and told me

her dad was murdered. I told her he wasn’t. If he had been, the medical examiner would have stumbled across it. MEs are like

that. It was easy to see she already had both feet firmly on the road of suspicion, and I told her I’d look into it. I did some checking. Henry Martins was a bank manager who left behind

a lot of family and a lot of clients, but his occupation wasn’t an opportunity for him to line his pockets with other people’s money.

I looked into his life as much as I could in the small amount of time I could allot for his daughter’s ‘hunch’, but nothing stood out as odd.

Two years later, and Henry Martins’ coffin is behind me on

chains as the wind increases in strength. And Henry Martins’ wife is trying to avoid anybody with a badge now that her second

husband has died, his blue fingernails the first indication that he was poisoned. Henry’s daughter hasn’t spoken to me because I’m no longer in the same position I was two years ago. It’s easy to let my mind wander and think of things that might have been. I could have done more back then. I could have solved a murder,

if that’s what happened. Could have stopped another man from

dying. The jury is still out on whether Mrs Martins had bad luck or bad judgement when it came to men.

The rain gets heavier, creating a thousand tiny ripples on the surface of the water. The caretaker is backing away, keeping his eyes on the water. Slowly the elements seem to disappear; so do the voices, and the vibrations. All that is left are the three corpses floating ahead of me, each one a victim of something – a victim of age, foul play, bad luck or maybe a victim of a cemetery’s lack of real estate.

The three workers have all come over beside me. Their excited

bursts of started but stilted observations have ended. We’re

standing, the four of us, in front of the water; three people are in it: it’s like we’re all pairing up for a social but with one person left over. The occasion demands quiet, each of us unwilling to say anything to break the silence building between us. More dirt slides into and mixes with the water, turning it cloudy brown.

One of the bodies sinks back out of view and disappears. The

other two are drifting towards us, swimming without movement.

I’m not about to jump in and pull them out. I’d do it, no doubt there, if the bodies were flailing about. But they’re not. They’re dead, have been for maybe a long time. The situation may seem

urgent but in reality it isn’t. Both are face down, and both appear to be dressed, and not badly dressed either. They look as though they could be on their way to an event. A funeral or a wedding.

Except for the ropes. There are pieces of green rope attached to the bodies.

The digger driver keeps squinting at the two corpses, as if his eyes are tricking him. The truck driver is standing with his mouth wide open and his hands on his hips, while his assistant keeps glancing at his watch as if this whole thing might push him into overtime.

‘We need to haul them in,’ I say, even though both bodies are

nudging against the bank now.

I had planned on staying dry today. I had planned on seeing

one dead body. Now everything is up in the air.

‘Why? They’re not exactly going to go anywhere,’ the truck

driver says.

‘They might sink like the other one.’

‘What are we going to grab them with?’

‘Jesus, I don’t know. Something. A branch, maybe. Or your

hands.’

“I’m not using my hands,’ he says, and the other two nod

quickly in agreement.

‘Well, what about rope? You gotta have some of that, right?’

‘That one there,’ the truck driver says, looking at the corpse closest to us, ‘already has some rope.’

‘Looks rotten. You gotta have something newer in the truck,

right?’ I ask, and we all look over at the truck just as we hear it start.

The caretaker is sitting in the cab.

‘What the fuck?’ the driver asks. He starts to run over to it, but he isn’t quick enough. The caretaker gets it into gear and pulls away fast. The coffin isn’t secure; it slides across the edge and hits the ground but doesn’t break.

Tley, come back here, come back here!’ The guy keeps running

after the truck, but the distance quickly grows.

‘Where’s he going?’ the digger operator asks.

‘Anywhere but here is my guess.’ I pull my cellphone from my

pocket. ‘You got some rope in the digger?’

‘Yeah, hang on.’

I phone the police station and get transferred to a detective I used to know. I tell him the situation. He tells me to sober up.

Tells me of course there are going to be bodies out here in the cemetery. It takes a minute to persuade him the bodies are coming up from the depths of the lake. And another minute to convince him I’m not joking.

‘And bring some divers,’ I say, before hanging up.

The digger operator hands me the rope. The truck driver is

back; he’s swearing as his partner uses the cellphone to call their boss for someone to come and get them. I tie an arm-length

branch around the end of the rope and make my way down the

gently sloping bank, intending to throw the branch just past the nearest corpse to bring it closer, but it turns out the slippery grass beneath my feet has other ideas. One moment I’m on the bank.

The next I’m in the water.

My feet are submerged in mud, the water up to my knees.

Something grabs my ankle and I lever forwards, my arms slapping the surface next to the corpse before I start sinking. I pull my legs from the mud, but there is nothing to stand on. This lake is a goddamn death trap, and now I know why it’s full of corpses.

These people came to grieve for the dead and ended up joining

them. The water is ice cold, locking up my chest and stomach and

cramping my muscles. My eyes are open and the water is burning them. There is only darkness around me, compounded by the

silence, and I can sense hands of the dead reaching to pull me deeper, wanting me to join them, wanting fresh blood.

Then suddenly I’m racing back to the surface, my hand tight

around the rope that is pulling me up. I kick with my feet. Point my body upwards. And a second later I’m right next to a bloated woman in a long white dress. It looks like a wedding dress. I push away from her, and the three men help me onto the bank. I sit

down, gasping for air. Both my shoes are missing.

‘Goddamn, buddy, you okay?’

The question sounds like it is coming from the other side of

the lake, and I’m not sure which one of them asked it. Maybe all three of them in unison. I lean over my knees and start coughing.

I feel like I’m choking. I’m shivering, I’m angry, but mostly I feel embarrassed. But none of the men are laughing. They’re all leaning over me, looking concerned. With two floating corpses

nearby, it’s easy to understand why nothing here is a joke.

‘There’s something else you need to know,’ the digger operator says. “I was trying to tell you before.’ He slips that last part into the conversation as if each word is its own sentence, and his face screws up slightly. He makes it sound like that whatever he has to say is going to be worse than what just happened, and I can think of only one thing that could possibly be.

‘Yeah?’

‘Marks. On top of the coffin.’

‘How did I know you were going to say that?’

Now it’s his turn to shrug. ‘Thin lines. Like cuts. They look

like shovel cuts,’ he says.

‘You think this coffin has been dug up before?’

“I’m not just thinking it, I’m saying it. There are definitely marks on the coffin that nobody here caused. Shit, I wonder if she’s empty.’

She. Like a plane or a boat, because the coffin in a way is a

vessel taking you somewhere.

We walk over to it. There’s a large crack running from the

chapter three

There is a natural progression to things. An evolution. First there is a fantasy. The fantasy belongs to some sadistic loser, a guy who eats and breathes and dreams with the sole desire to kill. Then comes the reality. A victim falls into his web, she is used, and the fantasy often doesn’t live up to the reality. So there are more victims. The desire escalates. It starts with one a year, becomes two or three a year, then it’s happening every other month. Or every month. Their bodies show up. The police are involved.

They bring doctors and pathologists and technicians who can

analyse fibres and blood samples and fingerprints. They create a profile to help catch the killer. Following them is the media. The media spin the killer’s fantasy into gold. Death is a moneymaking industry. The undertakers, the coffin salesmen, the crystal-ball and palm readers, then eventually the digger operators and the private investigators: we’re the next step in the progression, standing in the rain and watching as one travesty of justice reveals another.

I have shrugged out of my wet jacket and wet shirt, dried

off using a towel an ambulance driver gave me and pulled on a

fresh windbreaker. My shoes are still missing and my pants and underwear are soaking, but I’m safe from pneumonia. Nobody

is paying me any attention as I sit on the floor of the ambulance with my legs hanging out, looking over the scene of, at this stage, an indeterminable crime.

The graveyard has been cordoned off. The two police cars have

become twelve. The two station wagons have become six. There

are road blocks covering the main entrance, as though they are preparing to fight back an upsurging of angry corpses. There are two tarpaulins lying across the ground; on each one rests a well dressed but decomposing or decomposed body. A canvas tent

has been erected over them, protecting them from the elements.

Somebody has strung some yellow ‘do not cross’ tape around the tent. It keeps the corpses from going anywhere. There are men

and women wearing nylon suits studying the bodies. Others are

standing near the lake. They look like divers preparing for some deep-sea mission, only there are no divers here. Not yet, anyway.

There are open suitcases containing tools and evidence beneath the tent. The rain is still falling and the long grass ripples with the wind. The digger has been taken away, and the coffin has been

taken to the morgue.

I tighten my windbreaker, and reach around for a second

blanket. The inside of the ambulance is messy, as if it’s sped over dozens of bumps on the way: God knows how the paramedics ever

know where anything is. I wrap the blanket over my shoulders and let my teeth chatter as I watch the few detectives who have shown up. More will arrive soon. They always do. So far there hasn’t been much for them to do other than look at two bodies and a lot of gravestones. They can’t go canvassing the area because all the neighbours are dead. They have no one to question other than the caretaker, but the caretaker is off somewhere in a stolen truck.

The wind has picked up. Acorns are still falling, flicking off the tombstones and making small metallic dinging noises as they hit the roofs of the vehicles. All this extra traffic, yet no other bodies have risen up from the watery depths of whatever Hell is down

there. I glance over at the ambulance driver. He has nobody to save. He has nothing else to do than watch the show, bury his

hands in his pockets and keep me company. All of us are in that boat. He’s probably just hanging around until he gets the call that somebody is dead or dying, blood and limbs scattered across the highway of life that he’s cleaning up every day.

The buzzing of a media helicopter approaching from the

north sounds like a mosquito. I touch the outside of my trouser pocket and run my finger over the bulge of the wristwatch I stole from one of the corpses after we pulled it from the water.

One of the medical examiners, a man in his early fifties who

has been doing this for nearly half his life, comes out of the tent, looks around at the small crowd of people, spots me and then

heads over to a detective. They talk for a few minutes, all very casual – the relaxed conversation of two men who have delivered and received many conversations about death. By the time he

comes over he is sighing, as though being in the same graveyard with me is such tiring work. His hands are thrust deep into his pockets. There are small drops of rain on his glasses. I stand up but don’t move away from the ambulance. I have a pretty good

idea what the examiner is going to say. After all, I spent some time with those corpses. I saw how they were dressed.

‘Well?’ I ask, clenching my jaw to keep my teeth from

chattering.

‘You said there were three bodies?’

‘Yeah.’

‘We’ve got two.’

‘The other one sank again.’

‘Yep. Bodies will do that. Bodies do lots of strange things.’

‘What else?’

‘Schroder said to throw you some basic facts, but nothing

more. Just the same things he’ll be giving those vultures out there when he releases a statement in an hour.’ He points to the edge of the cemetery where the media are no doubt congregating behind

the police barriers.

‘Come on, Sheldon, you can give me more than just the

basics.’

‘Is that what you think?’

Suddenly I’m not so sure. One day everybody is your best

friend; the next you’re just a giant pain in the arse. ‘So, you’re going to make me guess?’

‘My guesses are supported by science.’

‘Well, science away.’

‘You saw the rope?’

I nod.

‘I’d say they all had rope attached at one point. But not so

much now.’

“I don’t follow,’ I say.

‘You probably figured we’re not dealing with homicides,

right?’

‘The thought crossed my mind.’

‘At least not in any traditional sense,’ he says. ‘Probably not in any sense at all.’

‘You want to clarify that?’

‘Why? You think this is your case now?’

“I’m just curious. I’m allowed to be curious, aren’t I? I’m the one who found these poor bastards.’

‘That doesn’t make them yours.’

‘You think I want them?’

‘You know what I mean.’ He looks back at the tent covering

the corpses. The wind has got hold of one of the doors and is

snapping it from side to side like a sail. An officer gets it under control and secures it. ‘Okay, let me back up a bit here. First of all, the two bodies we’ve got. Only one of them is intact.’

‘That’s got to be one of two reasons, right?’ I ask.

‘Yeah. And it’s the good one. Nobody tortured these people

or cut them up – at least that’s my preliminary finding. The

worst one is simply coming apart from decomposition. He’s

missing everything below the pelvic girdle, and what is there is held together mostly by his clothes. Hard to tell how long he’s been in the water, but it seems obvious that when we find the rest of him we’re going to find more rope. Could be piles of bones

stuck in the mud down there. The thing is, Tate, going by the

woman we found, I’m pretty sure these people weren’t killed and dumped in the lake. They were already dead. Dead and buried,

I’d say. Don’t know what originally killed them, but we’ll get there. We’ll get some timeframes too.’

I look past Sheldon to the grave markers all around us.

There are a few things going through my mind. I’m thinking

that somewhere out there is an undertaker or mortuary assistant saving money by reselling the same coffins to different families.

Coffins are expensive. Use them once, dig them up, dump the

bodies in the water; rinse down the woodwork, spray some air

freshener in, and make it sparkle with a coat of furniture polish.

Then it goes back on the market. Brand new again. None of those signs saying ‘as new, only one owner, elderly lady, low mileage’.

One coffin could do dozens of people.

‘You know you could buy a car for the same amount as a

coffin?’ the medical examiner muses.

‘That’s not it,’ I realise.

‘What?’

‘This isn’t about reselling coffins,’ I say.

‘What makes you so sure?’

‘Why throw the bodies into the lake? Why not just throw

them back into the ground? Or switch the coffins with budget

ones?

‘Yeah … maybe. I guess.’

“I wonder how many more bodies are down there.’

He shrugs. ‘We’ll know soon enough.’

If there are more bodies in the lake, the divers will find them.

I’ll be gone by then. It’s unrealistic to think somebody will keep me informed – I’ll learn the numbers from the papers. One

thing I learned in the years before I left the police force is that life and death are all about numbers. People love statistics. Especially nasty ones.

‘How old do you think this cemetery is?’ I ask.

He shrugs. ‘What? How the hell would I know that? Sixty,

eighty years? I don’t know’

‘Well, the lake has always been here,’ I say, ‘which means this might not even be a crime scene. Except maybe one of criminal

negligence.’

‘You want to elaborate?’

‘It’s not like people were getting buried here and suddenly

this lake appeared, pushing some of the graves deep into the

water. It’s not a stretch to imagine some poor management and

attempts at utilising space means some of these graves are too close to the water. Maybe some of the coffins have rotted from water damage and the bodies have been pulled into the lake, or there’s an underground stream sucking some caskets along.’

‘Not in this case.’

‘You sure?’

‘The woman makes me sure. She’s been in the water only a

couple of days. No time for your rotting-coffin theory. There are signs of mortician tricks that suggest she had a funeral, which is why I’m confident these people were once buried. In fact, she’s the reason we’re all here. She’s the catalyst here – fat stores and gases brought her to the surface, and she brought the others up with her.’

‘She’d do that, even if she was embalmed?’

‘She wasn’t embalmed.’

“I thought that…’

‘I know what you thought. You thought that everybody has

to be embalmed, that it’s law. But it’s not. Embalming slows

the decomposition for a few days so the body can be displayed

– that’s all it’s for. It’s optional.’

‘Can you tell if anything else has been done to the bodies?’

‘Like what?’