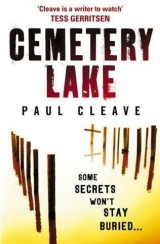

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter fifteen

David the boyfriend lives in a house that is almost as run down as Sidney the retired caretaker’s. The place hasn’t seen as much in the way of paint over the last few years as it has rust and spiders.

The guttering has corroded away, the windows are covered in

grime, the weatherboards warped and unwelcoming. It’s in the

middle of dozens of others, each one in need of a handyman’s

touch or a wrecking ball. I can’t figure out how David still lives here. I can’t figure out how anybody could live here longer than a week. But maybe he likes it and it’s a simple case of me not getting it. Perhaps this is the stereotypical pop-culture way to live.

Derelict is the new black. Grunge is in, being broke is in, making sure the house you live in looks like crap is in. He doesn’t own the place, but rents it, like all the other students in this area, which means he slips easily into the day-to-day routine of not giving a damn about the condition of the property, and the owners know

one day they’re going to bulldoze or burn it down anyway and

don’t care as long as the rent is paid. This isn’t suburbia; most of the people living around here are university students struggling to survive. Rachel Tyler was a student. I can’t imagine her staying here for more than a few days before returning home to grab a

few things or a good night’s sleep or the chance to step out of a shower cleaner than when she stepped in.

A young guy with studs in his ears and lips and nose opens the door. He must have real fun going through the security foreplay before boarding a plane. He’s squinting because the cloudy glare is too bright for him. His T-shirt reads The truth is down there with an arrow pointed to his crotch. All of a sudden, the last thing I want to know is the truth.

‘David Harding?’

“No, dude, he’s not here.’

‘Where is he?’

The guy shrugs. ‘Studying, I think. Or sleeping.’

‘Sleeping?’

‘Yeah, man, you know, that thing you do in the morning after

being out all night.’

“I thought people slept in the night.’

‘What planet are you from?’

‘An older one. Does he sleep here?’

‘Yeah, man.’

‘So if he’s sleeping, could it be that he’s sleeping here right now?’

He seems to think about it. ‘It could do, I suppose.’

‘Then how about you put that university education of yours to

some good use and figure it out for me.’

‘Whatever, bro,’ he says, then turns and walks up the hallway, grabbing the wall twice as he goes to make sure neither it nor him falls down.

I take a couple of steps inside, figuring Stud-face here is happy for me to do so but simply forgot to extend the invite. It’s colder inside than out – probably an all-year-round feature of these houses. The air is damp, and the carpet, wallpaper and furniture could do with a permanent dehumidifier. There are posters on

the walls but no photographs of friends or family. I can hear

mumbling from the other end of the house but can’t decipher it.

It sounds like hangover talk.

I keep walking. The hallway takes me into a kitchen straight

out of the start of last century, and with rotting food lying around that could be from the same era. The kitchen bench has a Formica top patterned with yellow flowers and strewn with the remnants of fast-food packets. The coffee plunger is hot. I pour a cup just as Studly comes through. He doesn’t seem surprised at all that I’ve invaded his house and made myself at home. I figure it’s a student thing.

‘He’s tired,’ Studly says, summing up the hangover in an

ambitious lie.

‘He’s this way?’ I ask, heading out of the kitchen and back into the hallway.

‘Dude, I said he’s tired. He doesn’t want to talk.’

I turn around and stare at him, and there’s something in the

way I look at him that makes him decide he doesn’t seem to mind any more whether I go and wake David or not, as long as I’m

not bugging him. He shrugs and goes about riffling through the fridge for something that could be food.

David Harding’s bedroom is dark and smells worse than the

rest of the house. I turn the light on, but it doesn’t really help much. On the floor is a double mattress with no base. It looks like it’s had a dozen people jumping up and down on it. David

doesn’t look up. He has his head buried in a pillow.

I crouch down next to him.

‘David.’

‘Go away’

“I need to ask you some questions.’

“I don’t care.’

There are clothes scattered across the floor, pages from work

assignments and text books piled on the desk and chair. Food

wrappers and crumbs cover the carpet. I open the curtains and

let in some light. He groans a little. I roll him over, and for the first time he takes a look at me. His hair is sticking straight up around the back and the left-hand side from where the pillow has crushed it. There are gunks of sleep in the corners of his eyes.

His skin is pale, suggesting he doesn’t get out much. There is something that looks familiar about him, and I put it down to

the possibility I might have seen his picture in the papers when Rachel disappeared. He looks lost, the kind of lost only somebody in their twenties looks when they’re still at university racking up the degrees with no idea of what they really want to do in life.

‘Drink this.’

‘Go away’

‘It’s hot,’ I say, ‘and you don’t want to risk me spilling it all over you.’

He sits up and I hand him the mug.

‘What the hell do you want?’

‘To talk to you about Rachel.’

‘Let me guess – her mum asked you to come here, right? She

still thinks I killed her.’

‘I’m working for Rachel, not for her mother. Did you kill

her?’

‘Fuck you, man. And get the hell out of my room.’

“I found her body’

He sits up straighter and tightens his grip on the coffee mug.

‘She’s dead?’

It’s such a simple question. There is no emotion there, just a look of complete surprise, his mouth slightly open and his eyes slightly wider. No tears, no anger, no frustration. Just acceptance.

Acceptance of a question I think he’s been asking himself over and over – the big ‘what if. And finally the answer. What if she’s still alive? What if she isn’t?

‘She was found yesterday.’

Are you sure?’

I hand him the ring. He sits the coffee on the floor so he can look at it. He turns it over and reads the inscription. Then he slips it onto the tip of his finger and slowly spins it around.

“I gave her this,’ he says. ‘It wasn’t long before she disappeared.

I promised her that when we graduated I’d take her away from

here and we’d never come back.’

‘She hated it here? Why?’

“I don’t think she really did. I guess that’s the thing about this city, right? You can love and hate it at the same time. I think she just felt claustrophobic here, you know? She wanted to see the rest of the world, and I was going to show it to her. Where did you find her?’

‘She was buried in a cemetery’

‘Huh?’

‘She had been put into somebody else’s coffin.’

“I don’t get what you’re saying. She was buried?’

The emotion is coming now. His hands are shaking a little,

and his eyes are starting to glisten over, just as I’ve seen it dozens of other times in those who have lost loved ones.

‘We were exhuming a body’ I say. ‘The person we thought we

were digging up was missing. Rachel was there instead.’

‘Who were you digging up?’

A guy called Henry Martins. Ring a bell?’

He shakes his head. ‘Why would it?’

“He was a bank manager. You sure you’ve never heard of him?’

‘Does it look like I ever needed a bank manager? How’d she

die? Was she buried alive? Oh, Jesus, don’t tell me that.’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘You’re not sure? Did you see her?’

‘Yes.’

“How’d she look?’

‘She was still wearing the ring,’ I say, which isn’t quite true.

SHow’d she look?’ he repeats.

‘She’s been dead two years, David. That’s how she looked.’

He runs both his hands through his hair. ‘Jesus,’ he says. ‘This isn’t right.’ He throws back the blankets and stands up. He’s

wearing a pair of boxer shorts, and his body is pasty white. He pulls on a pair of jeans.

‘It never is. Tell me what happened.’

‘What?’

‘When you last saw her, tell me what happened.’

‘Nothing happened. It was just a non-moment. I can’t even

remember.’

‘Sure you can. Everybody remembers the last moments.’

David’s moment turned out to be like any other. He had

dinner with her. They ate fast food while they studied. They

went to bed together, though he tells me the house was tidier

back then. They woke up together; he headed for class and she

went to find some breakfast. It was a slice-of-life moment that has probably been playing over and over in his head for the last two years. He’ll have been thinking about all the factors that had to come together for this to have happened. He could have

skipped class. His class could have been at a different time. Or hers could have been. They could have had breakfast together.

They could have had dinner separately the night before. Any link in the chain could have been broken and the result would be that they’d still be together.

The reality is, of course, they could have broken up or he could have got her pregnant and left her for a life of less responsibility, or she could have cheated on him. Young love can lead anywhere.

But it never should have led to this. He says he didn’t even know she was missing, that he figured she’d gone home that night and hadn’t called.

‘Was she having any problems?’

“None that she told me about.’

‘Anybody giving her a hard time? Hanging around? Anything

at all out of the ordinary?’

‘You don’t think I’ve been asked these questions? Man, I’ve

been over this with so many other people, and I’ve been over it with myself every single fucking day. I loved her. I still do.’

‘Where’d she go for breakfast?’

‘She ate at a university cafe. You guys already know that.’

I don’t feel the need to correct his impression that I must be a cop.

‘Humour me.’

He starts pacing the room. ‘She was spotted in there. She left around ten-thirty. She ate bacon and eggs smothered in tomato

sauce. I never figured out how she could eat that combination.

Then she left. And that’s all anybody knows.’

‘Was she supposed to meet anybody?’

‘She was going to class.’

‘Was she seeing anybody?’

‘What, like having an affair?’

‘Was she?’

‘Rachel would never have done that.’

‘Would you?’

‘Hell no. I loved her.’

‘So you can’t think of anywhere else she might’ve gone.’

“I don’t know, man. If I did, I’d tell you.’

‘Okay, okay. Who else can I ask?’

‘What?’

‘She has to have a best friend, right? Who would she talk to

when she was complaining about you?’

‘She didn’t complain.’

‘Then you must’ve been the perfect boyfriend.’

‘Alicia North. They’d go shopping all the time and they’d

complain about men. Rachel said she did it more for Alicia than for herself. But Alicia didn’t see her that day. I think Rachel did it because she loved shopping. It was kind of annoying. She used to make all these damn impulse buys.’

‘Where does Alicia live?’

“I don’t know. I haven’t spoken to her since.’

‘Ever heard of a woman called Julie Thomas?’

‘Umm … not that I can think of. Is she a student here?’

“No. You sure you haven’t heard of her?’

‘Yeah. Why?’

‘She went missing around the same time as Rachel. What

about Jessica Shanks?’

‘She go missing too?’ he asks.

‘You heard of her?’

He shakes his head.

‘What about Bruce Alderman?’ I ask.

‘Alderman? Umm … no, I don’t think so. Should I have?’

“I don’t know’

‘Did he kill Rachel?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘Can’t you interrogate him or something?’

‘He’s dead. He shot himself last night. But he says he didn’t do it.’

He stops pacing. ‘What? He shot himself? I … umm … do

you believe him? That he didn’t do it?’

‘Enough to keep looking into it.’

‘Her mum thinks it was me.’

“I know’

“I didn’t do it.’

I look into his eyes. There is sorrow there, I recognise it and I feel it, and though he doesn’t know it, that sorrow is a bond between us. He isn’t acting. His pain is real. Real enough that if I put him in the room with the man who killed Rachel, he would become a completely new man. He would cross a path that he

could not turn back from, and it wouldn’t bother him. He’d cross it again and again if he could.

“I know.’

‘And that Harry dude, what happened to him?’

‘Henry Martins. We’re not sure exactly. Look, David, don’t try to get back to sleep. The cops are going to be here soon. Just tell them what you know’

‘You’re not a cop?’

I hand him my card and take the ring back off him. “I used to

be, but that was a long time ago.’

chapter sixteen

There are no police cars parked outside the Tyler house. They’ve either been and gone or are on their way. There is, though, a car parked up the driveway that wasn’t there last night. Probably the husband. He’d have got the call seconds after I left last night, and rushed home. He didn’t put the car away. Didn’t get up this morning to go and move it. He’s waiting inside with his wife,

waiting for the news. Waiting to hear about his dead daughter.

I check my phone. It has one bar of battery life, three bars of signal, but it still hasn’t been connected to the network.

The door is opened before I get to it. Patricia Tyler’s wearing the same clothes she had on yesterday. She probably slept in them.

Or hasn’t slept at all.

‘Something’s happening, isn’t it,’ she says.

‘Yes.’

‘We’re finding out today, aren’t we?’

‘Yes.’

‘Did you know yesterday? When you came to my house, when

I let you inside. Did you know my daughter was dead?’

“I suspected.’

‘Yet you said nothing.’

‘I’m sorry’

‘You’re sorry’ she says, and her voice is calm and even, tired sounding. ‘They called fifteen minutes ago. They didn’t say

anything, but I could tell. They’re on their way to speak to us.’

There is nothing I can say to make her feel any better, so I say nothing. I wait her out, knowing she hasn’t finished.

‘You’re sorry, yet you came in anyway. You made me believe

there was a chance my daughter was still alive.’

I didn’t make her believe anything. I could have shown up

with her daughter’s hand in a plastic bag along with the ring and she’d still have held out hope. I think she’s still holding out for it now.

‘Can I come in?’

“I don’t think so.’

A man killed himself in my office,’ I say. ‘It was last night. He put a gun to his head and told me he had nothing to do with what happened to Rachel, and then he pulled the trigger.’

She doesn’t look shocked. Doesn’t look satisfied. She just looks tired, as if anything and everything is too much for her now. ‘I saw you on the news,’ she says. ‘It didn’t make you look good. Do you think he killed Rachel?’

‘He might’ve been lying. You can never have justice for what

happened, but this is as close to it as you can get. But if he was telling the truth, then there is still somebody out there who has to pay. That’s why I’m here. For Rachel’s sake.’

‘For Rachel’s sake,’ she repeats, and there is no inflection in her voice, and I can’t get a read on her reason for repeating it. ‘That reporter,’ she goes on. ‘She said your daughter was killed. So you know. And maybe that pain we share will take you further than

the police. Maybe it will make you fight harder for Rachel.’

She leads me through to the lounge. Her husband, an

overweight guy with grey hair and dark shadows beneath his

eyes, stands up from the couch, seems about to shake my hand,

then pulls it back as if the contact will taint the news he’s about to get.

‘Were you the one who found her?’ he asks.

‘Yes.’

How…’ He looks down, studies the carpet for a few moments

as if it’s going to save him from something, then carries on without looking back up. ‘How’d she look?’

It’s the same question the boyfriend asked. They want to hear

that she looked at peace, that she still looked good for a girl who was murdered two years ago. Only she didn’t look good. She

looked like she died hard.

‘Like she was asleep,’ I say, hoping they’ll believe the lie,

hoping that when they plead with the detectives to see her body they won’t be allowed to.

‘It’s hard to believe she’s really dead,’ he says, looking back up. His face is rigid, void of hope. Except for his eyes. His eyes are haunting. I have to look away. ‘It ought to be easier,’ he adds.

‘You’d think two years would have prepared us for this.’

He probably knows exactly how many days it’s been. I think

of my wife and daughter, and I think about what the last two

years have prepared me for. Fate came along and destroyed the

Tyler family, and a week later it destroyed mine.

‘People keep saying that time heals all wounds,’ he says. ‘They say we should get on with our lives. Like we’re just supposed

to forget all about Rachel. Like we’re supposed to give up on

wondering. Give up on our hope. They don’t get it. They think

it’s like losing a puppy or misplacing car keys. They talk without experience; they offer advice, thinking they know what we need to hear, sure that the best thing for us is simply to move on.’

‘But you know all of that, don’t you,’ Patricia Tyler says.

‘Why are you here?’ her husband asks.

‘For Rachel.’

‘Shame you weren’t there for her two years ago,’ he says.

‘Michael…’

‘I’m sorry. It’s just that, well …’ He doesn’t finish. He sits back down in the couch and starts to look around the room as

though he’s misplaced something.

‘I’ve spoken to David,’ I say.

‘You spoke to David!”

‘He said that Rachel liked to shop.’

Patricia looks to her husband. They stare at each other, the kind of look a couple share when trying to decide whether to let the rest of the world in on the big secret. It’s an innocent statement which I’m sure will have an innocent answer, but they’re both

looking for a different question and answer here, they’re wanting the answers to what happened to their daughter. They’re trying to figure out how her shopping got her killed.

‘Sure, she shopped,’ she says.

‘Did Rachel use a credit card?’

‘The goddamn bank sent us a bill,’ Michael Tyler says. ‘They

told us if we didn’t pay it they were going to get the debt collectors onto us. We explained Rachel had gone missing. Hell, it was

in the news, so they already knew. Only they didn’t care. Their argument was nobody had any proof of what happened to Rachel

and they shouldn’t end up footing the bill.’

‘It was awful.’ Patricia Tyler’s tears start to come now. For

a few moments she does nothing to try to stop them, just lets

them roll down her face as if she hasn’t noticed them. Then she raises a handkerchief and tries to dab them away, but they keep on coming. ‘Can you imagine that? Our daughter is missing, possibly dead – or, as it turns out, she was. Or is.’

‘Both, actually’ her husband interjects, and he looks close

to tears too, and he shrugs a little, as if unsure why he made the comment. I know the moment I leave they will fall into an

embrace neither of them will ever want to break.

And those heartless thugs at the bank register us with a debt

collection agency’

‘Do you have that last credit card statement?’

‘We have everything,’ she says.

‘Can I see it?’

‘Why?’

‘It might tell me where Rachel was that day, or in the days

before.’

‘The police already have a copy of it. It didn’t lead them

anywhere.’

‘But it might lead me somewhere.’

She doesn’t argue the point. She just walks out of the room,

leaving me and her husband alone in uncomfortable silence until she returns with the bill. She hands it over to me. I scroll down.

Clothes, CDs, more clothes. Petrol.

‘These are all standard places she went?’

‘They’re on all of her bills.’

‘Where was her car found?’

At the university. It was where she always parked it.’

And the florist?’ I ask, stopping my finger next to the purchase she made a week before she disappeared.

‘She bought flowers for her grandmother.’

‘Anything else here stand out?’ I ask.

‘Nothing.’

‘Okay. Can I take this with me?’

‘Don’t lose it,’ she says.

She walks me to the door. Michael Tyler stands up, seems

about to join us, but sits back down. The hallway is warm and

there seem to be more pictures of Rachel hanging up than there were when I was here last night, as if the Tylers thought they could use them to keep the bad news at bay.

‘The man last night. The reporter said his name was Bruce

Alderman. You haven’t said it, but you think he’s innocent, don’t you? That’s why you’re here.’

I think of the look in Bruce’s eyes before he pulled the trigger.

I think of the key in his pocket with my name on the envelope.

“I don’t think he did it,’ I admit.

‘Will you find who did?’

‘I’ll try. I promise.’

I’m halfway down the pathway when it strikes me. I turn back

around and Patricia is still standing there watching me, watching the person who two years after her daughter went missing came

along and told them all was lost.

‘The flowers for her grandmother. Was there an occasion?’

‘My mother died a week before Rachel disappeared. It was

one of the reasons the police thought she’d run away. Rachel and

my mum were close. For the first few years my mother helped

raise Rachel. The police assumed she was depressed and needed

to get away. She bought flowers to take out to the cemetery for the funeral.’

‘Which cemetery?’

‘Woodland Estates.’

Woodland Estates. The cemetery with the lake. The cemetery

with my daughter.

The cemetery where Rachel Tyler was found.