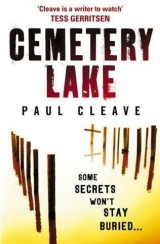

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Chapter thirty-five

I try to figure out what he’s saying. I don’t even know when

last night was. Technically it’s just been; it’s after midnight now.

But he doesn’t mean today. He means yesterday. Technically. He’s talking about twenty-four hours ago. A lot has happened since

then. It feels like two days have passed since I followed Father Julian from the church, but it’s only been one. Hell, it’s probably only a few minutes either side of that.

‘What?’

‘You’re going to need to come with us, Tate.’

I look down at my towel. I look at my dirty feet and the lines of blood on my chest.

‘I didn’t have anything to do with it.’

Landry looks me up and down. ‘No?’

‘No.’

‘You’re saying even though he had a protection order against

you, even though you were picked up at the church the morning

of the day he died breaking that order, and even though you were caught on film there yesterday evening, and you crashed your

car, drunk, a few minutes from the church around the same time Father Julian died, that you had nothing to do with it?’

I don’t bother answering. It’s hard to defend yourself when

you’re wearing only a towel. But I figure Landry or one of his buddies must have been dropping by the house on and off all day since I was signed out of the courthouse in the afternoon. That means Julian wasn’t found till around then at the earliest. Any earlier and I’d never have been released.

‘Put on some clothes, Tate. You’re coming with us.’

“I’m calling my lawyer.’ I think of Donovan Green but can’t

really imagine him being happy to take my call.

‘Get him to meet you at the station.’

I have nothing to put on except a pair of shorts and a T-shirt that have been building up dust in the corner of the bedroom.

Everything else is in the washing machine. I throw on a jacket and my running sneakers.

I’m put in the back of the car and driven away, and this time I’m handcuffed. Landry stays behind with some others to go through my house. At the station I’m reacquainted with the interrogation room. They lock me in, and the call I get to make to my lawyer isn’t brought up again, but that’s okay. I haven’t been having a good day with lawyers. I rest my head on my arms and close my

eyes, knowing I’m going to be waiting here a while.

Landry comes in an hour later, and he has Schroder with him.

That means one of them is going to be my friend while the other puts on the pressure. I already know who will play what role, and I figure they know I’ll know that too. They set up a video camera and point it so it covers all three of us. I can hear it recording.

Schroder sits opposite me and Landry stands. It’s pretty cold in here, especially as I’m dressed for summer.

Schroder sits a folder on the table and opens the cover. There are photographs of Father Julian in there. His head has been beaten in, blood all over his face and neck. His clothing is dishevelled.

One eye is open, but the other is closed because of the way his face is pressing against the floor. He doesn’t look like he died easy.

Not like I could have earlier on today out in the woods. His open eye has a tiny pool of blood in it. Schroder starts to lay the photos out on the table. There is a close-up one of Father Julian’s mouth.

His lips are open; his teeth are exposed and bloody. Behind them is a deep darkness.

‘Some ground rules first,’ Schroder says. ‘You know how this

goes, you’ve been on this side of the table, so we’re not going to try and play you. We’re just gonna lay out the facts and you’re gonna get to state your case. That sound good to you?’

I shrug. ‘Sure. What about my lawyer? You think it’ll sound

good to him?’

‘You can have a lawyer if you want one. We’re not going to

feed you that bullshit line about only guilty men wanting them.’

‘Let’s just get this over with then.’

He slides a piece of paper over to me. ‘Just sign this,’ he says.

I don’t read it over. I just check a few of the words to make

sure it’s the same form I used to slide over the table to people. It’s a waiver, saying I’m happy to talk without a lawyer present.

‘What’s the problem?’ Landry asks. ‘You decided maybe you’ve

got something you don’t want to share with us?’

I sign the form. The alternative is to phone Donovan Green

and get him down here.

The form disappears back into the folder. The photographs of

Father Julian remain.

‘The message is clear,’ Landry says.

‘What message?’

He looks at Schroder and shrugs, as if he really can’t believe what he just heard. Schroder lays out a few more photographs.

‘You didn’t want him to talk,’ Schroder says. And you wanted

to leave him a message. That’s why you cut out his tongue.’

hang on a second,’ I say, leaning forward.

‘Why are you in such a mess?’ Landry asks. ‘You’re covered in

blood. In dirt. What have you been doing? You’ve been burying

something?’

‘I was in an accident last night.’

‘And you were cleaned up. All the clothes you were wearing today are in your washing machine. They all have blood on them too?’ Schroder asks.

‘You’d have been better off dumping them, Tate,’ Landry says.

‘All those years busting people for this same kind of shit, I’d have thought you’d have learned more.’

‘When the hell did you make it a law that a man can’t start

cleaning up after himself?’

‘The way you’ve been lately,’ Landry says, leaning against the wall, ‘we’ve all thought it was a law you’d made.’

I look at their positions. One sitting. One standing. One my

friend, the other my enemy. The acting is going to be a stretch for only one of these men. Soon Landry will pace behind me, in and out of view, then he’ll lean over me. The game they said they wouldn’t play they’re already playing. They have to. They don’t know how to do it any other way.

‘Why don’t you tell us about Julian?’ Schroder asks. ‘Why were you following him?’

“I haven’t been following him, and I certainly didn’t do this to him. First of all, if I was trying to leave a message by cutting out his tongue, the only person that message could be for would be you guys, right? I mean, Jesus, it’d be stupid of me to have done that.’

‘Listen to him,’ Landry says, looking at Schroder but really

talking to me. ‘He thinks there’s some sense in all of this.’

“I didn’t kill him.’

‘Try selling us another story,’ Landry says. “Nobody in this

room has any false pretences about what you’re capable of, Tate.’

‘Look, Tate, cut us some slack here, okay?’ Schroder says. ‘You know how it works. You can sit there all night stonewalling us, but in the end we’ll learn what we need to from you. Why don’t you save us all some time?’

I look at the photos of the dead priest. There are eight of

them. ‘Why? So you can pin this bullshit on me?’

‘If you didn’t kill him, then what’s the problem? The evidence will prove that.’

‘Depends on how you’re going to look at the evidence. Seems

to me you’re already looking at it and don’t have a fucking clue how to read it properly’

‘We’re wasting our time,’ Landry says. ‘I say we lock him up

and tell his fellow prisoners he used to be a cop. Let them loosen him up.’

‘Yeah, good one, Landry’

‘Why were you following him?’ Schroder asks.

‘Like I said, I wasn’t following him.’

Schroder presses on. ‘What were you doing before the

accident?’

“I wasn’t following him.’

‘We know you weren’t following him at that point,’ Landry

adds. ‘He was already dead by then.’

‘We need to show him a few things,’ Schroder says, then he

stands up and walks out of the room. Landry doesn’t fill the

empty seat. He pushes his hands against the top of it and leans forward.

‘You used to be one of us,’ he says. ‘What in the hell

happened?’

‘What do you think?’

Before he can answer, Schroder steps back in. He has a

cardboard box full of plastic bags. I can’t tell how many there are as they all blend into one. He starts laying them out on the table.

‘The watch,’ he says, ‘used to belong to Gerald Weiss. He was

buried with it two years ago. So how is it you’ve come to own

it?’

“I found it.’

‘There are two ways you could have got it,’ Landry says.

‘Either you stole it off a dead man when you were in the water, or you stole it off a dead man when you were pulling him out of his coffin.’

‘Even you’re doing a shitty job of trying to believe that,’ I say, and Landry looks pissed off. ‘You’re trying too hard here. And one day that’s going to come back and kick you in the arse. You’re going to try too damn hard, and people are going to suffer for it.’

‘You’re either a thief or a killer,’ Landry says firmly, as if they are one in the same. “I think that’s why you were so damn keen to help out with the exhumation of Henry Martins. You knew

who was going to be in there. You wanted to try and control the situation. But the problem was the corpses, right? They floated up. If they hadn’t, we’d never have known about the others.’

‘Look, cut the routine or I’m gonna change my mind and ask

for my lawyer.’

Schroder slides over another bag. It has the newspaper articles I found in Alderman’s bedroom. ‘You’ve been holding back on

us,’ he says, adding the printouts I made when sketching out

the timelines of obituaries and the missing girls. ‘You knew long before us who was in the ground.’

‘That’s because I used to do this too,’ I say, and it’s true. I used to do this, and between the times I did and the times I haven’t nothing really has changed. Violent acts are still a huge part of this city, as are the grey skies and the rain waiting at the threshold of every cooling hour. Bad things happening to good people.

There are kids in this city being born, being loved, growing up into the choices that make them good or bad. There are kids out there without any chance at all. Some will become good, some

will become evil, some are born and tossed into dumpsters. I was part of the world that tried to correct all of that, the world that tried to keep some of it in check. But somewhere along the way I lost track of it all. I fell into the abyss.

‘Nobody seems to have forgotten that as much as you, Tate,’

Schroder says. ‘You’re nothing like the man you used to be. You used to be a real stand-up guy. And now you’ve got a DUI hanging over your head; we’ve got you for theft, for stalking, and you’re looking real good for murder.’

‘ Without any evidence you can’t hold me here without charging me. That means I’m here on my own merits. That means I’m free

to get up and leave.’

“No, you’re not free until I say you’re free,’ Schroder says.

‘We’ve got a techie going through your computer files. You’ve

been following Father Julian since the day Sidney Alderman went missing. And these newspaper articles. How is it some of them

are originals? To me, that suggests they were cut out as the girls went missing. How’d you get them?’

Bruce Alderman gave them to me. He left them in my car

when we drove to my office.’

Schroder slides another plastic bag over. It has a small envelope inside with my name written across it. There are bloody smudges across it. For a brief moment I’m back in my office, the smell of burning metal and blood in the air, a pink mist creating a cloud over the caretaker’s head that has just been distended by a bullet.

‘What was in here?’ Schroder asks. ‘The articles? See, the

articles aren’t folded up, and they’d need to have been folded to fit in this envelope.’

“I can’t remember.’

‘We found writing samples at the church. This is Bruce

Alderman’s handwriting.’

‘So?’

‘So what else have you stolen?’ Landry asks.

“I haven’t stolen anything. That envelope has my name on it,

so whatever was in there was mine.’

“He wrote you a letter? A confession? A suicide note?’ Schroder asks.

‘No.’

‘Thought you couldn’t remember what was in there?’

“I can’t.’

‘But you can remember what wasn’t in there.’

‘Memory is a funny thing.’

‘Cut the crap, Tate,’ Landry says.

‘It was the watch, okay?’ I say, and it sounds believable enough.

‘Alderman had the watch. I don’t know how he got it, and when

he gave it to me I didn’t know who it belonged to.’

‘Bullshit,’ Landry says.

‘Then you ought to shut up until you can prove otherwise.’

‘Out of all the people in this city, why’d he come and see

you?’

I shrug. “I don’t know. I think it was because I was the face he connected to what was going on. I was the one who found the

bodies. I was the one who came along with the exhumation order and started all of this.’

‘You kept things from us,’ Schroder says. ‘You stole evidence

that would have helped us piece things together quicker. That

ring you took from Rachel Tyler – Jesus, Tate, let’s not forget you took the ring from Rachel Tyler. The timeline would have

changed. We’d probably have caught the person who started all

of this.’

It’s true. But the moment that coffin opened and I saw a dead

girl, I had no choice. There were other dead girls because of me, because of a decision I failed to make correctly two years earlier.

How could I not take the ring? It led to suicide. It led me to murder. It led me to drunk driving and to being taken into the middle of nowhere where I should have been left.

‘All these innocent girls,’ Schroder says, spreading out the

articles, one bag for each girl. ‘Do you even care?’

‘Of course I do.’

‘He doesn’t,’ Landry says, ‘otherwise he’d be helping us.’

‘You’ve turned one of your rooms into an office,’ Schroder

says. ‘Into a command post.’

‘You’re charging me with that too?’

‘Just tell us, damn it,’ he says, getting angry now. ‘You were following Father Julian for a reason. What do you think he did?

You think he killed Sidney Alderman?’

He leans back in his chair.

“No, I don’t think that’s it,’ Schroder continues. ‘You wouldn’t be following him for that. You wouldn’t care about one angry old retired caretaker getting taken out. So there’s more to it. You were following him because you think he had something to do with

the dead girls. Your office is dedicated to that case, and to Father Julian. You have pictures and articles pinned up all over the walls.

You think the two go hand in hand. We were looking at Sidney

Alderman as a possibility. And more so after he disappeared. We thought he ran. But not you. You kept looking at Father Julian.

He was on our radar simply because everybody connected to the

graveyard was on it. Only Alderman made a bigger blip, and

when he disappeared his blip overshadowed everybody else’s. So we kept looking for him. It’s as though you knew somethingIt’s as though you gave up looking for Sidney Alderman because

you didn’t think there was a point. Either you thought he was

innocent or you thought he would never show up again. It’s just like two years ago with Quentin James. Which is it?’

‘You tell me.’

‘You think Julian killed those girls. We’ll know soon whether

your thoughts have any foundation. In the meantime, tell us what happened to Sidney Alderman.’

“I don’t know’

‘But you knew to stop looking for him. Why did you focus on

Father Julian?’

“I wasn’t focusing on him.’

‘Why did you kill him?’

“I didn’t.’

‘This is going nowhere,’ Landry says. ‘Show him the

weapon.’

‘The weapon?’ I ask, immediately confused.

A smirk appears on Landry’s face. ‘The weapon, Sherlock.

Like I said earlier, you really learned fuck all from your years on the force. We searched your house, remember? What, did you

think we wouldn’t find it?’

Schroder lifts the last plastic bag from the box and puts it on the table. Inside is my hammer from home. It’s covered in blood.

And I already know it’s going to belong to Father Julian.

Chapter thirty-six

‘You’ve been following him for a month. You think he’s guilty of murder. You’ve been parked outside his church every day before the protection order, and some days since. And you want us to

believe you had nothing to do with his death,’ Schroder says,

putting the murder weapon down slowly, as if carefully balancing a cup of water filled to the brim. He puts it in the centre of the table so we’re all within reaching distance. Maybe he’s hoping I’m going to make a break for it. I’m sure Landry is. He’s hoping this can all end right now.

‘Where did you find it?’

‘Where you left it,’ Landry answers.

“I want my lawyer now.’

‘Yeah, guilty people always do,’ Landry says to Schroder

before turning back to me. ‘Come on, Tate, you know how it

goes. You’ve seen it before and you used to hate it too.’

“Hate what?’

‘When the perp keeps on denying it even after we’ve got so

much evidence against him.’

‘You’ve got nothing.’

“Nothing? Are you fucking kidding me?’

‘Tell us again why you were following him,’ Schroder asks.

‘Come on, Tate, if he was guilty, then let us help you. I mean, hell, if it turns out he killed those girls, we’ll probably end up giving you a medal. Just tell us what happened. We’re all on the same team here.’

“I didn’t kill him,’ I say, but my team mates don’t believe me.

I want a drink.

‘Give us a few minutes alone,’ Schroder says, and Landry

looks angry, but I know it’s an act. I know they’ve cued up their conversation before coming in here and this is the point where Schroder becomes my friend.

Landry walks out without saying anything else. It’s part of

their game.

‘You have to give me something here, Tate, or I can’t help

you.’

I figure it’s best if I play the game too. But before I do, I decide to give him something.

‘Father Julian knew who killed those girls.’

‘What?’

“He told me he knew. And Bruce Alderman, he buried them.

He told me that.’

‘What? Why the hell didn’t you tell us that?’

I explain to Schroder my conversations with the priest,

detailing my pleas for Julian to tell me who had done it, even touching on the frustration I felt. I can see Schroder wondering how far he’d have pushed it if he’d known that Father Julian had been confessed to. I tell him about Bruce Alderman and what he said about dignity before elegantly blowing his brains out.

‘You should have told us,’ he says. ‘We could have convinced Julian.’

“I doubt that.’

‘We could have done something, Tate. Anything. But instead

you let a whole damn month slide by and now it’s too late. That’s why you were outside his church, right? You weren’t following Father Julian. You were watching to see who came to see him.

T>u were waiting in case the killer showed up, only you didn’t know who the hell you were looking for.’

“I had to do something.’

‘You fucked up.’

‘I know’

‘And now Father Julian is dead. And you’re in a world full of

shit.’

‘It’s an abyss.’

‘What?’

‘Come on, Carl, you know me. You’ve known me for nearly

fifteen years.’

‘Which is why this is hard for me too. We found the hammer

in your garage.’

‘And that’s why you’re going to let me leave.’ It’s time to play the game.

‘What?’

‘You’ve got nothing to hold me here.’

He looks down at the hammer in such a way as to suggest

maybe I’ve forgotten it’s there. But I haven’t.

‘You found it in my garage.’

‘Yes.’

‘Okay, well, first of all you don’t even know if it’s my

hammer.’

‘That’s not the …’

‘Second,’ I say, and I hold up my hand and start counting off

my points. ‘You’re going to print it and find my prints aren’t on it.

You’re going to think a guy who used to be a homicide detective was dumb enough to clean off his fingerprints but not the blood, was dumb enough to keep the weapon, was dumb enough to

leave it in his garage for anybody to find.’

“Not dumb, but drunk,’ he says.

‘And that’s exactly my point.’

‘What?’

‘Three,’ I say, counting off another point with my fingers. ‘And this one is the kicker. This is the reason I’m about to get up and walk out of here.’

Schroder leans back. He knows what’s coming.

‘The timeline. See, we know the timeline, Carl, but the problem is the guy who planted the hammer there didn’t.’

Schroder says nothing. He knew I’d figure it out, but was

hoping it wouldn’t be this quickly. Or he was hoping to rattle me enough that I’d give him something more, maybe tell him about

Sidney Alderman.

‘You think he died around midnight,’ I say, not because he told me, but because that’s when I saw the person leaving the church, the person who I thought was the priest. The killer knew my car was there, but he didn’t see me because I was covered in ground fog. He probably figured I was passed out drunk in the front

seat because that’s what I was used to doing. He stayed in the shadows where he thought he was out of sight.

‘But I didn’t make it home. Only the killer couldn’t have

known that. He drove to my house and replaced the hammer

he had stolen to kill the priest. He didn’t know I was following him. What he couldn’t know was that I would be involved in an

accident. Your boys came and locked me up. My car was towed

away, and after you found Julian was dead, you would have had

it re-towed, this time as evidence in a murder investigation. You had it brought here and every inch of it has been gone over. No blood from Father Julian and, more importantly, no hammer,

right? And it’s not like it got logged along with my wallet and cellphone. I didn’t have it on me. And you would have searched the area of the crash, would have searched the roads between the graveyard and accident. You found nothing. Until tonight. So

how’d I put it there?’

‘You could have dumped the hammer, picked it back up

tonight. Maybe that’s why you’re covered in dirt.’

‘Why would I dump the hammer? I couldn’t know I was going

to crash. What would be the point of dumping it, just to come

back tonight to retrieve it and hide it in my garage?’

Schroder says nothing.

‘Then the whole tongue thing. Like I said earlier, why the

hell would I cut it out? Because I didn’t want him talking? That’s the sort of message you want to leave when there are others who can still talk, right? A gang thing. But not in this case. This time it was designed to make me look guiltier. It would look like I was pissed at him for talking to you guys and complaining that I was following him.’

He starts tapping a pen against the table in a slow rhythmic

pace, then smiles. ‘Well done,’ he says. He leans forward and starts packing up the photographs.

‘So you know I didn’t kill him, but you haul me down here

anyway’

‘Come on, Tate, you know how it is.’

He’s right. I do know. There are two things that bug me.

The first is, why plant the hammer in my garage, and not the

tongue?

‘Somebody still killed him,’ Schroder says.

‘Uh huh.’

‘You can help us out there.’

‘You shouldn’t have fucked me around, Carl. You should have

just asked for my help.’

‘Hey, don’t go playing the victim here, Tate. You almost killed a woman last night. Hell, maybe you still did – last I heard she was stable, but that don’t mean shit and you know it. Father Julian had to take a protection order out on you and you kept breaking it. You were there the night he died. You’re involved, Tate. Julian died, and if you’d been upfront a month ago maybe he’d still be alive now. Sidney Alderman is nowhere to be seen and you’re

acting like he’s dead. Same goes for Quentin James. You need to start giving me some answers. Look, you know that by keeping

these from us —’ he leans forward and touches the bags with the jewellery and the articles – ‘you slowed down our investigation.

Things would be different. We might have looked further. We

might not have pinned all our beliefs on Alderman. Fuck, Tate, we needed this one. There’s been so much shit lately with the

fucking Carver case, and that’s just the tip. You’d know that if you gave a shit, or if you read a newspaper.’ He pauses, takes a pencil out of his shirt pocket, rolls it across his fingers, then snaps it in half. ‘Look, you get the point. We needed something to work out, not just for the victims and for their families, but for us. People don’t have faith in the police any more, Tate. Jesus, it’s hard to blame them. That could have all changed, but you held back on

us.’

‘Was I in the news today?’

‘What?’

‘The papers, Carl. Was I in them? The accident?’

‘Not the papers. The accident was too late for that. But you’ve been on the news all day’

‘Since this morning?’

‘That’s what all day means.’

‘Then why the hell aren’t you asking yourself the obvious

question?’

‘Which is?’

‘Why would the guy who planted the hammer in my garage

not take it back out after seeing the news? He must have known being in jail would clear me.’

I can tell from his expression that Schroder hadn’t thought of it. ‘Maybe he didn’t see the news.’

‘Come on, Carl, you know just as well as I do that these guys

always read the papers and watch the news.’

He taps one half of the broken pencil against the table. ‘This is going to be a long night,’ he says. ‘We’re going to get this sorted.’

‘Then I’d better make myself comfortable,’ I answer, and I lean back in my chair.