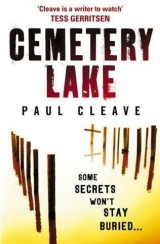

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter forty-three

I’m out of shape. I can feel it in the first few strides. My socks slide on the floor and the chase is almost over before it begins.

I can hear the officer behind me, and a moment later the first one I saw appears at the other end of the corridor, running towards me. I pull the door; it opens into the corridor and blocks the path of at least one of my pursuers. Then I grab the basin of holy water and throw it in the opposite direction. It clatters on the ground without hitting anybody, but a moment later there’s a

sliding sound and then the man behind me yells ‘Shit!’ as he slips and falls. It forces his partner to slow down. I keep running.

I hit the line of trees as the two men burst from the building behind me. I change direction and keep running, not slowing

when my feet crash into tree roots or get punctured by pieces

of bark and acorns and stones. I can hear them following me,

closing the distance. I make a left and a right, and keep making them. I can see the beams of their flashlights falling on me, on trees around me, but then they appear less frequently The rain is pouring down heavily, drowning out all sounds of pursuit. I keep running, altering direction through the trees. Suddenly I’m out of the trees, heading across the cemetery between gravestones and graves. I have no idea where I am, and the best I can hope for is that a cemetery at this time of night in this kind of weather is a hard place in which to follow anybody.

A car comes towards me from the road and I duck down behind

a gravestone. It passes me by. There is yelling and confusion.

I look out and see one of the officers is only a few metres away.

He comes towards me and I duck back down. He passes me and

keeps going. He’s making quick ground. I crawl towards another grave and then another, staying hidden for a few more seconds.

I look back up – the officers are now twenty metres away. I stand up and run deeper into the cemetery. My feet sink slightly into the grass. Another car travels along the road and I have to hide again.

The cold air makes it harder for me to breathe, and I start sucking down oxygen in deep lungfuls that burn and make me dizzy.

I hide behind a tall grave marker and look back in the direction I’ve come from. I can see flashlights moving around the trees

and graves not far from me. I’m unsure now of what direction to run.

I stay low and move further away, putting more grass and

graves and metres between me and the flashlights. More patrol

cars arrive – I can see their headlights, hear doors banging.

I reach another cluster of trees and rest for thirty seconds or so. My feet are aching and probably bleeding but I don’t want

to look. I check back in what I believe, though am not certain, is the direction of the church. I panic for a moment about

whether my wallet or keys are in the jacket I left behind, and I quickly check. My keys are in my pants pocket, and my wallet – I remember now – is still at home. I stick with the direction I was heading. I’m aware of more cars arriving, and rest for a few more seconds behind another grave marker to watch the show.

Their pooling location shows me where the church is. There are no sirens sounding, but there are plenty of flashing blue and red lights from patrol cars through the trees and from others moving through the cemetery grounds. I keep running. And running

I think about the extra weight Schroder told me I’d put on, and I can feel every kilogram of it slowing me down. The contours

of the land change. I head up and then down and then up again, hitting slight slopes that feel steeper than they really are, and they soon make it difficult to see anything behind me. I reach another section of the cemetery but still have no idea where I am. I forge ahead, trespassing over the dead. I keep looking back. No more light. No more patrol cars. Not that I can see. More trees ahead of me, another stretch of graves. I burst through another patch of bushes and garden, then suddenly I’m at a fence line. I want to scale it but I can’t, not yet, not for a few more moments, not until my heart rate slows some and my body is convinced enough to keep going.

The fence backs on to somebody’s house, an old weatherboard

home with a huge gap between the house and the garage. I drop

down into the back yard and I run for the gap. There is no other fence. I reach the road and look left and right. I know where I am.

There is a bus stop a few metres away from me. I walk down to

it and then decide it’s a bad place to be waiting. I cross the road and sit down behind a hedge. I take some slow deep breaths in an effort to bring my heart rate back to normal.

I start back towards the car. Ten minutes later I’m heading along the same road as the cemetery. I can see lights and commotion way up ahead, but the car is a good two blocks short of it. I unlock it and duck into the driver’s seat, traipsing mud and leaves and blood into the floor-well. I sit the envelope of photographs on the passenger seat. It’s been a bit bent out of shape but is mostly dry except for two of the corners. I start the engine, but leave the lights off until I’ve rounded the first corner. I think about the shovel in the boot and I figure tonight wasn’t the best night to go digging anyway. Besides, there’s something unnerving in

the thought of returning Dad’s car to him after it’s been used to drive a corpse around. That hadn’t been on the agenda when

I borrowed it.

By the time I get home I’m bordering on exhaustion, though

I don’t feel tired. It’s sensory overload. without the benefit of alcohol to keep things running smoodily without sleep, I know

I’m going to crash and burn.

I take a quick shower and check my banged-up feet. They’re

grazed, but not as bad as I’d expected. Then I take the pictures from the damp envelope and separate them so they can dry out.

I don’t look at them closely. Not right now. I can’t. But I can’t leave them out either in case Landry or Schroder show up. I wipe them dry with a tea-towel, then put them into a fresh envelope and throw out the old one. In the corner of my bedroom I lift up the carpet, figuring that since it worked so well for Alderman and Julian, it’s got to work well for me too.

I hit my bed and fall asleep without even willing it.

chapter forty-four

258

Nobody comes to my house during the night. I reckon the police will have narrowed down last night’s visitor to the church to one of three people – me, the killer or a reporter. They’ll have found my jacket and my shoes, but even if they recognise them there’s nothing on them to say they’re mine, only DNA, and that’ll take eight weeks to arrive. Landry and Schroder will undoubtedly be thinking of coming to talk to me; they’ll be wondering if they can bluff me into admitting I went into the church, though they’ll know they can’t. I know the game. And anyway, all I have to

say is the same person who planted the murder weapon in my

garage also planted my clothes to try to complete the frame job, and that’s also what I’ll be saying in two months’ time when they get DNA from hair follicles caught in my jacket. Landry will

have gone through all of this, hitting it from all sorts of different angles, without coming up with one that will help him cement

a case against me. I’m betting that in the end he’ll know his

argument and he’ll know my argument, and he’ll know that mine

is stronger.

Of course all of this is moot if I can’t get back into the cemetery and dig Alderman up before Monday

The overnight rain has stopped and for the moment the

clouds are mainly dispersed. I open up the curtains and dump my sopping clothes into the washing machine. It seems that getting messed up at night is becoming a habit. Then I make coffee,

wondering at what point in the human evolution coffee became

such an important ingredient, and I figure if nothing else in this world, no matter what happens in the future, coffee will sure as hell be around a lot longer than religion. I carry the photographs I’ve pulled back out from under the carpet into my office. I go through them all again, but recognise only Bruce among the

various boys and girls. Then I turn them over. They all have names and dates on the back. Just first names. The dates go back twenty four years. I start flicking through them, the names rushing out at me from the past month, the names connecting the dots.

I put the photos down. I stand up and start to walk around

my office, my breath quickening. Excitement is starting to build, the kind of excitement I haven’t felt in a long time, not since working homicides in my previous life, not since the thrill of feeling things coming together and knowing you’re heading for

the finishing line.

There are five girls in these pictures. Four of them share names with the dead girls who’ve been found. I have no idea where the fifth girl is, but I have a first name. Deborah. There are three boys too: Bruce, Simon and Jeremy. I have no idea where Simon and

Jeremy are either.

I go back to Rachel’s photo and turn it over. I remember

the other photos I’ve seen of her on the wall of her parents’

house. Then suddenly I’m back in Father Julian’s office. Bruce was like a son to me, he’s telling me. Like a son. Were all these people like sons and daughters to Father Julian? I think they

were. I remember looking at the pictures of the missing girls a month ago and thinking how similar they were, how their killer had a type. I was right and wrong. His type wasn’t based on

characteristics the girls shared, or body type or age. It was based on who these people were. He targeted them specifically because they were all related.

chapter forty-five

The house looks a little tidier than the last time I was here. I figure their lives are no longer on hold. The news they’d been dreading has arrived, and though they’re struggling with it, they’re starting to move forward.

“I don’t know whether to thank you or hate you,’ Patricia

Tyler says, and she really seems to be trying hard to make up her mind.

‘Can I come in? Please, it’s important.’

“I don’t know. The truth is I hardly know what to think any

more.’

I pull out the photograph from Father Julian’s collection. The rest are in the envelope, tucked inside my jacket pocket. I hand it over. I know immediately that she recognises it. Her knuckles turn white as she holds it ever tighter.

‘Where did you get this?’ she asks, though I’m pretty sure she already knows.

‘Please, can I come inside?’

She takes a step back for me to move in, and leads me down

the hallway.

‘Michael isn’t here,’ she says, then pauses. ‘Thankfully’

The photographs on the wall are all the same as the last time

I was here, but I see them a little differently now. Michael Tyler, who is holding her hand when she is maybe five years old, doesn’t appear in any earlier photographs.

We sit down in the lounge. Patricia Tyler offers me a drink and I tell her I’d like some water. She gets up and returns a minute later, carrying two glasses. She sets them down carefully on a pair of coasters and I ask the question I came here to ask.

‘You’re right,’ she says. ‘It all seems like a lifetime ago. Longer, when I think about it really hard. Rachel was four when I met

Michael and six when we got married. It was like starting a new life. I could only hope that Michael would one day look at Rachel as if she was his own.’ She takes a sip of water. ‘He did see her that way too. He loved her, and the past years – well, they’re killing him as much as they’re killing me.’

And Father Julian, he was Rachel’s biological father,’ I say, and it isn’t a question.

‘It’s been over twenty years, and you’re the first person to

ever ask me about him.’ She looks back down at the photograph.

“I remember this moment,’ she says. ‘It was the day Rachel turned two. I was leaving work early. My mother would look after Rachel while I was at work. She made a cake and we had a party, but

Rachel didn’t understand the occasion.’

I remember a similar party for my own daughter. I remember

getting carried away and buying too many gifts. Emily was excited tearing them open, but her concentration would drift from her

new toy to the wrapping paper the toy had come in, and she

would run around the room as if she was on a sugar high while

friends and family watched and laughed and played with her.

She would have five more birthdays. Rachel Tyler had seventeen more.

‘This moment,’ she says, and she twists the photo towards

me for the briefest of seconds. Rachel is sitting in the corner of a room with her head resting on her knees, her arms wrapped

around her legs, and her eyes either half open or half closed, ‘was at the end of the day. I was getting ready to take her back home and she didn’t want to go. She wanted to stay with my mother,

because she thought that it meant there would be more presents tomorrow’

She pauses, and I have the feeling her mind is travelling down a path of a possibility not taken. She’s thinking that if she’d left her daughter at her mother’s house on that day nearly twenty

years ago, Rachel would still be alive.

“I don’t even know why I took the photo,’ she says. “I mean,

I remember taking it, and I remember asking her to smile, but

I don’t really know why I went about it. I’d already taken lots that day. I sent it to Father Julian. He’d asked for one. This, this is all about Father Julian, isn’t it? About Stewart? You having this photo. You took it from him. And he’s dead and Rachel’s

dead and there’s something to that, isn’t there? That’s why you’re here.’

‘What happened after you had the baby?’

‘Things were already in motion before Rachel was born. We

both knew I could never have an abortion. He wouldn’t allow

it, and anyway, it wasn’t something I would have considered.

I also knew he couldn’t be with me. I was going to be a single mother, but it wasn’t going to be the end of the world. I had

to give up work for the first year and a half. Stewart told me he would support me. We set up bank accounts. Once I got married, Stewart didn’t have to pay as much but he did keep paying.

I never asked him for anything more, and he never asked to see Rachel.’

I think about this for a few moments, sure that there is something else here. If Julian did Father those other children, was he paying child support to all of them? If so, how did he get the money?

I keep the conversation moving along, but make a mental note to come back to this.

‘Did Rachel know?’

‘When she was old enough she figured out Michael wasn’t

her real dad. She asked who her father was, but I never told her.’

She takes a drink. “I could really do with something stronger. Can I get you something?’

‘Water’s fine,’ I say, and I take a sip to show just how fine it is.

“I guess water’s fine for me too. I know how it sounds, getting pregnant to a priest of all people, but, well, I don’t regret it. Things were different back then. Father Julian … huh, it sounds so funny when I call him that, doesn’t it? The father of my child, and here I am calling him Father Julian instead of Stewart. I wonder if that means anything.’

“I don’t know.’

‘Look at me, I’m starting to ramble.’

“No, please, it’s all important.’

‘Back then Stewart was a young man, and he was very, very

striking. Almost insanely handsome. I think women were going

to church just to see him, not to hear what he had to say. He

had this – well, this magnetism – and it was more than just his looks. Everybody liked him; he was very charming, very likeable.

But he was also lonely, really lonely, and seemingly vulnerable, and somehow that made him even more appealing. One day that

loneliness became too much for him, for me, and we, we …

well, you know the rest. Anyway, he would always be quiet after we … you know, after we were together in that way. He was

intense too, and even though he knew he was making a mistake,

neither of us could help ourselves. He would tell me that when he was around me it was like somebody else was taking over, like he was a different man. I think he was a good man trapped in the wrong profession.’

‘Did you ever tell him that?’

‘More than once. But he said the priesthood was a calling, that he could help people, that he could do more good with a collar than without one. It was hard to watch. He was so dedicated to the church, it pained him every time we were together. In the end, I finished it, I had to. I didn’t want to, but what choice did I have?

It was tearing him apart. A month after we stopped seeing each other, I found out I was pregnant.’

‘What happened when you told him?’

“He wanted to do the right thing, only the right thing didn’t fall in line with his big picture of right things. It was like every day he was fighting a personal war within himself. I think that war was there his entire life. He was never going to leave the priesthood to be with me, and he couldn’t stay being a priest if others found out. So we both agreed to keep it quiet. I also stopped going to church.’ She dabs her knuckles into the bottoms of her eyes and pulls away some tears before taking another sip of water.

‘Did Michael know?’

‘He knew. I had to tell him. Can you imagine if he hadn’t

known? Every day he would wonder. He would think maybe

I was sleeping with so many people that I didn’t know who

Rachel’s dad was. I told him, and he wasn’t angry or disappointed.

He was relieved, for some reason. I’m not sure why exactly. I

think maybe knowing a priest had got me pregnant was much

better than thinking I’d slept with some drug addict or criminal.

Purer, or something. If that makes sense.’

It does, in a weird kind of way. ‘Did you keep in touch with

Father Julian?’

‘In the beginning, of course, but after I met Michael I didn’t really want to involve Stewart in my life any more. He seemed to understand. Then the day Rachel turned sixteen he stopped the

payments and I didn’t ask him why, because I knew. Sixteen was the cut-off date. I never saw him over those years. If it wasn’t for my mother, well…’

‘He presided over your mother’s funeral?’

‘My mother had continued to go to his church. It’s what she

would have wanted.’

‘Your mother didn’t know who the father was?’

“I refused to tell her.’

‘So Father Julian, he saw Rachel that day?’

She takes another sip of water, and when she pulls the glass back she seems to be studying the edge, looking for some microscopic flaw.

‘He saw her. Then a week later she goes missing. That’s the

connection, isn’t it? That’s why you’re here. If I had told Rachel he was her father, would things be different now? Is that the reason

she’s dead? Because I took her to my mother’s funeral?’

I know what answer she wants to hear, but I can’t offer it to

her.

‘Do you know if Father Julian ever had any other children?’

I ask.

‘It’s my fault,’ she says, and she starts to cry.

I clutch my glass of water, unsure whether to sit next to her, whether to put a hand on her shoulder and try to comfort

her. ‘None of this is your fault,’ I say, and it sounds generic because that’s exactly what it is. ‘But please, this is important. Did Father Julian have any other children?’

She leans back and stares at me. ‘Other children? I… I never really thought about it. He could have, I suppose. But I doubt it.’

“How did he get the money to send you?’

‘I… I don’t know. But Father Julian is … I mean was a good man. He would have done what it took.’

I pull the rest of the photographs out of my pocket and hand

them over to her.

‘There are names on the back,’ I say.

She looks through them but doesn’t recognise any of them.

‘There is no way these can all be his children,’ she says, but I think she knows there is a way. I think she can see the resemblances ‘These payments he made to you, they were credited directly

into your account?’

‘Of course. It was the only way’

‘Do you still have any of the statements?’

‘I… I suppose I do,’ she says, and I’m sure she does. I’m sure Patricia Tyler is the sort never to have thrown away anything from the last thirty years.

‘Would you mind finding me one?’

‘Why?’

‘Because if I can get his bank account number, then if he did

father any other children I can find their names.’

‘Do you think …’ She pauses, unwilling or unsure how to

continue. ‘Do you think all these girls who died … do you really think they’re related?’

I hold her gaze. She stares right at me and I tell her yes. She pulls her hand to her mouth as if to hold it closed from whatever she wants to say next.

‘Then you already know who these girls are,’ she says. ‘They’ve been identified.’

‘Not all of them.’

‘What?’

‘There are five girls in these pictures.’

‘Five? Oh,’ she says, and she gets it immediately. She gets that there is one more girl out there who I need to find. “I know where they are,’ she says, and she disappears for a few minutes before returning with a bank statement from five years ago.

‘It’s the last payment he made,’ she tells me.

I look at the statement. It doesn’t have Julian’s name on it. Just his account number, along with the word ‘Rachel’.

‘Can I take this?’

‘Of course.’

I finish off my water and she walks me to the door. ‘The police, are they close to finding who killed him?’ she asks.

‘They’re getting there.’

‘But you’re getting there quicker, aren’t you.’

‘Yes.’

‘Can you promise me something?’ she asks.

“I’ll do my best,’ I say, already knowing what she is going to ask.

‘Promise me you’ll find him before something happens to that

other girl. Promise me that when you find him, you’ll make him pay for what he has done. For Rachel. For the others. For all of us. Make him pay, and make sure he can never hurt another girl ever again.’