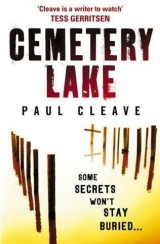

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter twenty-one

The church is bathed in sunlight on one side and shade on the

other, the two halves separated by a thin line like good and evil. It looks like there’s probably a difference of twenty degrees between the two. The stained-glass windows look dull and fogged up with age. The concrete brick around the edges of the shady side has speckles of mould. The gardens have low-key and low-maintenance shrubs spaced out about a metre apart. There aren’t any weeds, but that’ll probably change now that Bruce is gone.

Mine is the only car out front, and there’s nobody inside the

church either. Except, of course, for Father Julian, who appears from a side door to the right of the altar when I’m about halfway up the aisle. Maybe I passed through a motion detector. Maybe

he’s been hanging out all day for the chance to trap some soul into a conversation about God. But the way he moves towards

me makes me think he’s been waiting for me to show up.

‘You’re here,’ he says gravely.

‘We need to talk.’

‘You’re right. We do.’ He looks paler than yesterday, as if a

chunk of his faith has slipped away during the night. Or been

stolen. ‘We need to talk about Bruce. Though to be honest I don’t know if I can. I don’t think I can talk to you.’

‘Father Julian, please, you have to …’

“I don’t know, Theo,’ he says, glancing at the large envelope

in my hand. Some of the colour is coming back to his face, and the look in his eyes suggests it’s coming back on waves of anger.

‘Bruce was … well, Bruce was like a son to me. What you’ve done …’

“I didn’t kill him.’

His expression doesn’t change. He looks as if he was prepared

to hear me say that, and equally prepared to dismiss it. He looks like a man straggling to stay in control. ‘This is not the time or especially the place for your lies.’

“I didn’t touch him.’

‘Oh, you didn’t touch him, did you?’ he says, his voice getting louder now, and I realise it’s the first time I’ve ever heard a priest yell. ‘Then how in the hell did he end up dead!’

‘He shot himself. There was nothing I could do.’

‘You sure found yourself able to do something two years

ago.’

‘That was completely different.’ Now I’m the one getting close to yelling. And you know that. You damn well know that.’

“I told you that Bruce was a good boy’ he says, his arms going out to his sides and his hands flicking forward, as if trying to discard something sticky from his fingertips. ‘I told you he had nothing to do with those girls dying. I told you! Why couldn’t you have listened? You’ve shown so much trust in me in the past, why couldn’t you have shown it now?’

‘Goddamn it, Father Julian,’ I yell, and the words don’t make

him step back – in fact he takes a small step forward. ‘I didn’t kill him! Why the hell don’t you pick up the phone and make a call

and speak to anybody down at the station or at the morgue and

ask them what happened? They’ll tell you.’

‘He was a good boy’ he says, much quieter now.

‘Maybe he was. Part of me certainly believes he was. So how

about you give me a hand here and help me clear his name? Bruce told me he was innocent; that he buried the bodies but that he

didn’t kill those girls. How about you help me, or are you too caught up with those assumptions of yours?’

He looks at me for what feels like a long time, as if inside

somewhere he’s searching himself for the right thing to do. The time it takes him suggests he’s either searching real hard or he’s slipping on just what the right thing is these days.

‘I’ll listen to you, Theo, just one more time. Then you have to promise me you’ll never come back here.’

‘Once you hear what I have to say, you won’t ask me to …’

He shakes his head and cuts me off. ‘Promise me,’ he says.

‘Under the eyes of God, inside His church, promise me you’ll

never come back here.’

It’s a tough decision, but I make the promise.

‘My office. We’ll talk there.’

I follow him through the side door. The corridor is dimly lit, and we pass other doors and plenty of draughts – churches are full of draughts. He leads me into a small, dusty office that is cluttered with old-looking books and mismatched furniture. He

takes a seat behind his desk. The sun has arced around in the sky and is shining direcdy on him. It makes his face look whiter, almost glowing. Like a halo. The dust particles floating in the air are all a bright white. The light makes the stubble on his face look patchy, and it takes some of the anger out of his eyes and makes them look tired. There’s a crucifix hanging on the wall behind him. Jesus has a downcast look about him, as if he’s bored by it all, as if he’s seen every church office there is to see and after two thousand years of it he’s about had his fill of churches. The entire office looks as though every night somebody sneaks in here and alters everything slightly It’s the same way my place looks when I can’t figure out where I left my wallet or keys. I sit down opposite him.

‘If I’d helped you last night, maybe…’ Father Julian hesitates.

‘Well, who knows?’

‘I didn’t kill him.’

Father Julian sighs. ‘What do you want from me, Theo? Did

you come for somebody to forgive you? Because you’ve come to

the wrong place.’

‘Did you know that Bruce owned a gun?’

“He doesn’t.’

‘It sure looked like he did.’

‘Is that supposed to be funny?’

“No. But think about it. If I was going to kill him, why would I take him back to my office? You think I’d shoot him in front of my desk so the whole world would know about it?’

“I … I suppose not. I don’t know. I don’t know what to think.’

‘You know me better than that. You know that if I was going

to kill him I’d have taken him somewhere else.’

His jaw tightens and his eyes narrow slightly, and the look he gives me is the kind of look I never want to be given again. It’s one of disgust and disappointment. Finally he leans back in his chair and forms a steeple with his hands, touching his fingertips to his chin. He looks like he’s praying. Jesus looks down on him but doesn’t seem to be listening.

‘Come on,’ I say. ‘You don’t have to like it, but it’s a good

point.’

He nods. ‘What else did Bruce tell you? Did he know who

killed the girls?’

“He didn’t say. He just said to talk to his father. The only person I can think of who Bruce Alderman would be burying those girls for is his father.’

‘You think Sidney killed them?’

‘It’s possible.’

‘So what do you want from me? To tell you about Bruce? I’ve

already told you, he was a good kid. There is one more thing,

though, and I want you to think deeply on this. Yesterday he was alive, and today he isn’t.’

I don’t answer him. I just let him have his say, knowing the

sooner he gets everything off his chest, the sooner I can get on with things, and the sooner I can get my little girl back into the ground. The world is definitely fucked up when the goal of the day is to bury your daughter.

‘What happened after Bruce’s mother died? What happened

to Sidney?’

‘What?’ He looks shocked.

‘His mother. Ten years ago, when she died, what were things

like?’

He breathes out heavily, reinforcing just how much of an

ordeal it is to have me here.

it was the same thing, I guess. It was like one day he was alive, the next day he wasn’t. Though it wasn’t even really that. It’s not like he was dead. He just became … lost. They both did.’

And?’

And what? People become lost when that kind of thing happens.

Come on, Theo, of all people you don’t need an explanation on

that. Sometimes people never recover, or they recover in the

wrong way. And some people are lost in a way you can’t ever put your finger on.’

I think of Sidney Alderman digging up my dead daughter.

I can safely say I could put my finger on dozens of different reasons why the old man is more fucked up than he is lost.

‘Did either of them ever give you a confession?’

‘Come on, Theo, you know I can’t answer that.’

‘There were four of them in that lake, Father. So far the police have identified only two. Soon they’ll know all four.’

‘Four girls,’ he says. ‘What a waste of young lives.’

‘Well, now’s your opportunity …’

Suddenly it hits me. Father Julian’s anger can’t all be directed at me. It must also be directed at himself.

‘Yesterday I said there could be others in the coffins, but

I never said they were all girls. Or that they were young.’

He starts to say something—probably to protest that somehow

he heard or that he guessed – but he gives up the pretence and says nothing.

‘Jesus, you knew! You fucking knew!’

‘Theo!’ he yells, banging his fist down on the table. ‘Enough!

How dare you use …’

‘How dare me?’ Now it’s my turn to bang my fist down on the

table. “How dare you! You knew all along and did nothing? You

did nothing? How can that be?’

He doesn’t answer, and the silence that falls between us then is unexpected, as if we’re both too aware that what we say next may damage irrevocably whatever relationship we have.

‘What was I to do, Theo?’ he asks, almost in a whisper now,

and the question seems genuine, as if he really wants me to come up with other options when there are none. ‘You know the rules.

You can argue them, and you can hate them and you can rant and rave about the injustice of it all, but you know, Theo, you know the deal.’

‘One of the Aldermans confessed to you. One of them killed

those girls!’

“That’s not what I said, and that’s not what happened!’

I stand up and open the envelope and tip it up in the same

manner I did when I found it. The articles spill out in the

same way. I brush my hand over them, fanning them out like a

deck of cards. Father Julian’s eyes are pulled to them.

‘You already knew the girls were in there. You knew they were

dead.’

‘Sit back down, Theo.’

‘These are the girls we could have saved. What was it you said to me yesterday when I told you why this case was important

to me? You said it wasn’t my fault. You were right and you were wrong. See, I thought it was completely my fault. But not now.

Now I share that burden with you.’

He reaches out and touches the articles, picking some of them

up. I watch his eyes, but they don’t scan over any of the words.

The more he shifts the clippings around, the more dust floats

up in the air. I’m not sure what he’s looking for. None of the disappearances made the front pages. There are no huge headlines or by-lines. Maybe if one of them had been a rock star or the

mayor’s daughter, things would have been different. Though

that’s about to change. Tomorrow Rachel Tyler is going to be all over the news. And the other girls too. People other than their friends and family are going to care. People are going to look at the names and faces and wonder how the hell their city became

a breeding ground for the kind of violence needed to take these

young women away, and for the kind of ignorance to let it happen without asking why.

it’s so easy for you, isn’t it, Theo? It always has been. Guys like you think they can just come in here and get what they want.’

I’m not sure what he means by guys like me. ‘You have these

great expectations that all you have to do is ask and I’ll break the confessional seal and tell all. You don’t think it hurts? Huh? You don’t think that hearing all the poison coming from these people takes its toll? Don’t you think I want to be able to pick up the phone and make the world a better place?’

‘Then why don’t you? These girls, you could have saved

them.’

At what cost? You still don’t get it, do you? You think if this was just about me I wouldn’t do it? If it was just a matter of getting fired and losing my church, I’d pull the pin for the greater good. But this isn’t about me, Theo. It’s not about you either. It’s not about those girls out there. It’s about God. About our faith.

It’s about not breaking one of the oldest rules in the church.’

There are so many angles from which to attack his argument,

but for what point? He’s right and I’m right and we both know

it. And there’s nothing we can do. He has to stand by his beliefs, and I have to stand by my anger with him for not having done

something to prevent all of this.

‘That’s how you knew Bruce was innocent. He wasn’t the one

who confessed.’

‘We can’t go down this road.’

‘What road?’

‘The one where you start twisting all the boundaries, where

you ask who didn’t confess so you can narrow down your suspect pool.’ He runs both hands through his hair, then wipes them

down the front of his cassock.

“I think I’ve already narrowed it down,’ I say, and I start to scoop the articles back up.

it wasn’t Sidney Alderman.’

Part of me wants to lean forward and pick him up by his

collar and shake him until all that I need from him falls from that locked vault inside of him where he keeps secrets. Another part is thankful. He won’t give up these secrets, and he’ll never give up mine either.

‘You’re letting a murderer get away’ There is no conviction

behind my words. It’s a last-ditch effort, and one that I don’t expect to get me anywhere.

He seems to know this, it haunts me.’

If I tell him what Sidney Alderman has done to my daughter,

will it change his views? I don’t think it will. The priest’s ideas about what Sidney Alderman is like are all outdated. He built up a friendship with the guy thirty or forty years ago, and that’s how he still sees him. I wonder what it would take – whether there is a limit to how much pain there is – for Father Julian to accept that his faith and his convictions simply aren’t worth it. Is there a number? A dozen dead girls? A hundred?

‘Sidney Alderman. Tell me where he is.’

“I don’t know’

‘Did he kill those girls?’

“I want you to go now, Theo. And I want you to remember

your promise.’

‘But you can tell me about him, right? You can at least give me some history there.’

‘Sidney Alderman is a very sad man, Theo. Like you, he has

lost his family. Surely you remember how you felt the day Emily died. Surely you can empathise.’

Of course I remember. But I didn’t go around digging up

graves.

‘What happened to him two years ago?’

“I don’t follow’

I finish putting the articles into the envelope. One of them said he retired two years ago. Is that enough? People become killers when there is a trigger. When there’s a defining moment that makes somebody snap. I figure it’s more likely Sidney Alderman would’ve snapped ten years ago when his wife died, not two years ago when he retired.

‘Somebody has to pay for this,’ I say.

‘Somebody already has.’

‘But not the right person.’ I tuck the end of the envelope back into itself. ‘The police are close. All of this, ifs unravelling. You had your chance to help, but you didn’t take it. This was your chance for redemption, Father.’

‘Don’t do anything stupid, Theo. Bruce Alderman, he was a

good man. And Sidney – well, inside he is a good man too, and one who right now is attending to his son. Respect that. Let him mourn, and let the police deal with him.’

I walk to the door and Father Julian doesn’t get up. He doesn’t make any attempt to follow me.

“I can’t do that,’ I say.

He shakes his head, but doesn’t offer any more words of

wisdom. I leave him in his office and I walk back past the pictures of Jesus and his buddies. I wonder what they would think of the priest’s decision to keep the secrets shared with him to himself, whether they’d agree with his convictions or whether they’d tell him he was a fool. I wonder if right now Father Julian is praying for guidance.

At the front of the church is an alcove in which a registry

– thick and divided up into sections, the covers leather with gold script across them – rests on a pedestal. It’s sorted alphabetically, and those sections are broken down chronologically. I go through the pages, looking for more connections between the girls and

the times they went missing. I can’t find anything. There’s also a large reference map pinned on the wall; it has the cemetery

divided up into numbered sections like a street map. It’s all I need to find my next two locations.

The first one is a grave. It’s close to the back of the houses further up the street, about as far away from the church and the lake to the east as it can get while still being within the boundaries of the cemetery. I drive as close as I can before getting out and walking. There is a pathway that leads through some more trees, and suddenly I’m in an area of the cemetery that feels isolated.

I figure Alderman won’t be back anytime soon, so he’s not about to drive past my car and see that I’m here. I figure he’s sitting in a bar somewhere getting drunk, or he’s driving around, trying to work out where exactly to put my daughter. Or he’s parked up

on the side of the road, coming to his senses, wondering what

in the hell he’s doing. Maybe getting ready to bite down on a

bullet. Like father like son. Only that’s not a real possibility. Ten years ago, maybe, Alderman might have been the kind of guy to

question his actions. But not now.

The day’s getting brighter. Getting warmer. But I still feel cold inside. I walk around the gravestones, each one a story, each one a memory. Some good, some bad. These people all influenced

other people’s lives. They made differences. They met other

people and paired up and made little people while they made

futures together. Some died of old age. Others of disease. The messages on the gravestones are all similar. They’re sentiments, they’re statements, they’re final messages left to the world in the hope they will never be forgotten.

The one I want is tidy – no weeds, no long grass – but there are no flowers there either. I stand in front of it for about a minute before heading back to my car.

The second location is a large shed at the far northeast corner of the cemetery. It’s separated from the cemetery first by a wooden fence, then by a line of poplars. It’s about the same size as my house, but there are no inner walls or partitions to hold up the roof. It’s full of garden tools and sacks of grass seed and plant seed. There’s a tractor and a ride-on lawn mower and a digger.

The tools that were needed yesterday to exhume Henry Martins

were here all along, parked in a row. Instead contractors came and used their own equipment, and I wonder how different things

would be now if they hadn’t. I take a look at the place, but nothing stands out – there are so many possible murder weapons in here, if we take a week to examine each of them. This shed could be a crime scene.

There is a stack of cinderblocks beneath one of the benches.

Hanging up on a nail near the window is a coil of green rope.

I reach up and roll it between my fingers. It’s made up of hundreds of individual strands of what looks like hemp. It’s the same stuff that was connected to the bodies, and would have swelled when

it got wet. Thousands of people in this city probably use it.

I walk over to the digger. There is fresh dirt on the teeth

of the scoop. Sidney Alderman used it to bring my little girl up into the light. He probably laid her in the giant claw and drove her back here in it. I look around for Emily, but she isn’t here.

The shed could easily be the place where four young women

met their deaths. I stand in the centre and slowly turn around, covering each angle with my eyes. Two wheelbarrows. Pieces

of plywood. Buckets. Boot prints with chunks of dirt; bits and pieces of wood, tarps, ropes, workbenches. A horrible place to die. The air is musty, and I can smell oil and grass clippings.

There are cobwebs and stains and warped boards and cracks in

the glass. There are patches of rust in the roof and plastic buckets set below to catch the rain. There are shelves full of mechanical parts – levers, cogs, engine bits, most of them rusted.

I climb into the digger and start it up. The seat is uncomfortable, and has sharp splits in the vinyl where the foam bleeds through and looks like snow. I pull up a lever to slide the seat back. I’ve never driven one of these machines before, but the simplicity of the levers and pedals makes it easy enough after a few minutes’

practice. The digger vibrates as I roll forward. It bounces up and down with every small dip in the shingle road. The wheels leave deep imprints in the wet lawn.

I drive back to the grave.

Getting my daughter back is the priority, and anything that

happens in between I’ll put down to God’s will. That ought to

keep Father Julian happy.