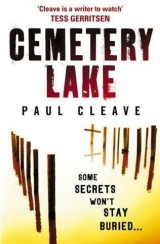

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter thirty-seven

Schroder was right and wrong. Right that it was going to be a

long night. Wrong about us getting it sorted. Landry showed

up on cue, but their routine at trying to shake something loose from me was ruined by the murder weapon. It was planted, they

both knew it, and that was the problem. They’d have had a better chance if they hadn’t found it. They held me long enough to go over the same questions and until they were satisfied the people going through my house had searched enough. And satisfied I

wasn’t going to offer them any further information. I could tell Landry was itching to keep me locked up, and that Schroder was tempted to go along with it, but in the end they had nothing to hold me on. Even the blood and dirt on my body I explained

away as a bad fall while I was out walking trying to clear my head.

Nobody bought it, but it didn’t matter.

A guy gives me a lift home in a patrol car. He doesn’t even

attempt conversation.

My house is locked up and I still don’t have my keys, so I get inside using the same busted window as before. Schroder never

mentioned the window, and I guess maybe he figured out why.

My house isn’t any tidier since the police have scoured their way through it. The articles and pictures from the bedroom I’d set up as an office have all gone. All that are left are pinholes in the walls.

The computer is gone, my notes are gone, even the whiteboard

has been taken. Landry will trawl through everything and he’ll get me back in to answer more questions —S maybe even later on today.

I make some coffee, and the caffeine wakes me enough to

realise I’m so tired I don’t even know what my next step should be. I haven’t had time to compile my thoughts on Father Julian being dead. Haven’t had time to consider how much it alters my investigation. Was he killed because he knew a killer’s secrets? Or for another reason?

The coffee tastes good but not good enough to consider

making another. I head down to the bedroom. Everything is

messy. The mattress has been tipped up and thrown back on the

base. All the drawers have been pulled out. The wardrobe has

been opened and everything inside pulled out.

I head down to the laundry and check the washing machine.

At some point the wash cycle was stopped. The clothes I put

in there have all gone. There are bloodstains on some of them

from the accident and from the trip into the woods, but those

bloodstains are mine.

I take a quick shower. Daxter stands in the bathroom and

watches me. I feed him and he seems appreciative.

It’s almost six in the morning before I climb into bed. I reckon Landry and Schroder will probably be going through the same

motions. I start to set the alarm, but in the end I can’t decide what time to set it for, so I switch it off. I bury my head into the pillows and try to get to sleep.

chapter thirty-eight

The house is full of warm colours and my neighbour’s face is

frozen with cold emotion.

‘What do you want to borrow my phone for, Theo?’

‘Because mine isn’t working.’

‘You think the police bugged it? They could have. They were

there all night. That was one stupid thing you did.’

“I know.’

‘After you losing your little girl and everything. Real stupid.’

‘Can I borrow your phone or not?’

Mrs Adams stares at me for a few seconds without saying

anything, and I can tell she’s really debating the issue. She doesn’t want me inside her house. This woman who looks like everybody’s grandmother and who brought cooked dinners to my house at

least once a week for almost a year after Emily died. This woman who I would occasionally find weeding my garden or trimming

some bushes. There was always a wave and a smile and a good

word that things would be okay, that Emily was with God, that

everything would be okay.

“I don’t know,’ she says. ‘You could have killed her.’

‘That wasn’t my intention,’ I say, as if that could possibly

excuse it. She doesn’t pick up on the comment, and instead stands aside.

‘Don’t take too long.’

Mrs Adams stays a step behind me, as if suddenly she thinks

I’m not only a drunk driver, but also about to steal one of the thousand knick-knacks covering the tables and bench tops.

‘Phonebook?’ I ask.

She sighs, and I have the impression that if she’d known in the beginning I was going to be this much trouble she wouldn’t have let me in. She rummages through a kitchen drawer and pulls out the white pages.

I call the hospital and ask after the condition of Emma Green.

It turns out that’s the girl’s real last name – Donovan Green wasn’t faking it after all. The nurse tells me she can only give information out to a family member.

‘Can you just tell me if she’s doing okay?’

‘When are you guys going to learn you can’t just keep chewing

up our time with questions all day long?’

‘What guys?’

‘Reporters,’ she says, almost spitting the word out. My guess

is that if she knew who I was it would only get worse.

I make my second call, this one to the morgue.

‘It’s Tate.’

‘Tate? My God, I heard about what happened. Are you doing

okay?’ Tracey asks. She’s the first person to have done so, and it feels kind of nice.

‘Doing okay? I guess that depends on your definition. Listen,

I need to ask if you can help me out on a few things.’

‘Tate, I’m sorry about everything that’s happened, but you

know I can’t help you on anything. Not just because of the last few days, but you stole that dead girl’s ring right out of my morgue.

I had Landry down here asking me about it this morning and

I didn’t know what to tell him.’

‘I’m sorry I had to put you through that.’

‘Yeah, well, I’m sorry too. Because now I’m the one who’s

getting a reprimand. This could end up being serious. For all I know, I could get suspended. Or worse. I gotta go.’

‘Listen, Tracey, please, it’s important.’

“I can’t.’

‘It’s the girl. That’s all.’

‘What?’

‘I need to know how she’s doing. The hospital won’t tell me.’

“I don’t know how she’s doing.’

‘But you can find out, right?’

‘You’re really pushing it, Tate.’

‘Please. It’s important.’

‘Call me back in five minutes.’

“I gotta come down there anyway. Put my name on the list. I’ll see you in a few hours.’

‘Look, I can’t just…’

‘Thanks, Tracey. I gotta go.’ I hang up before she can object.

Mrs Adams doesn’t seem too impressed that I’m taking up

so much of her time. Scattered across the kitchen are baking

ingredients that must all have come together to form whatever

fantastic-smelling thing is turning brown in the oven.

I make another call. My mother answers, slightly out of breath, as if she’s just run in from the garden.

‘I’ve been trying to call,’ she says. ‘Your cellphone isn’t switched on.’

“I lost it.’

‘And your home phone is disconnected.’

“I forgot to pay the bill.’

‘Is it true what the papers are saying?’

“I haven’t seen the papers.’

“I should have done more,’ she says.

‘What?’

‘This is my fault. I should have seen what was happening to

you ever since the accident. But don’t worry, we’re here to help you now.’

‘It’s not your fault. Anyway the reason I’m calling is I want to borrow a car.’

‘A car?’

Dad hardly uses his, right? And you two can share yours while

I’m using it.’

‘What’s wrong with yours? Oh,’ she says, figuring it out. “I

don’t know if it’s a good idea.’

“I’m not going to wreck it, Mum.’

“I don’t…’

“I need this, okay? I need you guys to trust me.’

‘Of course we trust you. But won’t they have taken your licence off you?’

‘They went easy on me because of my history’ I say, which is

a complete lie. My licence has been taken off me. If I get caught driving I’ll be heading straight back to jail. There’ll be fines. It’s the Quentin James factor.

‘I’ll bring it over to you,’ Mum says. “I’m sure Dad won’t

mind.’

We both know that he will. I hang up the phone and hand the

white pages back to Mrs Adams.

“I wouldn’t be trusting you,’ she says, then she offers me one of the muffins she’s just baked, as if some grandmotherly gene inside her can’t prevent her from reaching out. I grab one before she can change her mind, figuring it’s the healthiest thing I’ve eaten in weeks.

‘You know, Theo, I don’t mean to sound hard on you, not after

everything that’s happened, so please, don’t take this the wrong way, but it’s never too late to pull yourself together. We’re always next door if you need some help along the way’

I thank her for the use of her phone and for the muffin. She

gives me another one to take home with me. If more people were as forgiving and as helpful, maybe we could cut away some of the cancer that has set into the bones of this city.

It’ll take my mother an hour to get here with the car, so I kill some time by going to buy a newspaper. I keep thinking people

will notice me, that they’ll know who I am and what I have done, but nobody pays me any attention because my photo isn’t in the paper, only my name. The guy at the shop knows me, though,

because I’ve been coming here for years. He looks at me, looks down at the front page, and looks at me again. He seems to search for something to say, and I think all his angry one-liners trip over each other and he ends up saying nothing. He even gives me the right amount of change. I get back home and read the article.

It’s all about the accident. About me. It doesn’t paint a pretty picture. I read the article about Father Julian but it doesn’t reveal anything I don’t already know. At least my name isn’t mentioned here – yet.

I switch on the TV and watch a couple of minutes of the

morning news. Father Julian’s murder is the headline, and it looks like it’s going to be a busy day for the media. Casey Horwell gives a report. She talks about the murder weapon being found and she says where, offering my name as if she knew all along what I was capable of, her smirk suggesting she could see this coming even if the police couldn’t. I wonder how in the hell she found out where the weapon was found and who her source is. She talks about

Father Julian’s tongue being removed. I get angry just looking at her, and have to turn the TV off or risk throwing the remote at it.

I start to tidy the house and do some more laundry. Then

I spend a few minutes in my daughter’s bedroom. The police came through here last night, but they haven’t messed it up, just left things slightly askew. They showed some respect. They searched this room and found nothing except a lonely shrine and evidence of an even lonelier parent. Daxter looks up at me from the bed.

He follows me back down the house and I fill up his food bowl.

Six months ago I had a spare bedroom that seemed to be

a magnet for all the crap in my life that I couldn’t seem to fit anywhere else in the house or garage. These days it’s an office – or at least was until last night. I sit down at the desk and drag a pad out from the drawer. I start writing down the names and the dates of the women who were killed. I start compiling as many of the notes as I can remember, but the last four weeks have been a haze of alcohol, of guilt, of anger at the priest and at myself, and the small details have all slipped away, drowned beneath an ocean of self-resentment. I do the best I can with the details I remember, and I start to create another timeline.

When my mother arrives she looks around the house, unable

to stop herself from commenting about the mess, the smell, the stuffy air, the broken window. She looks me over. The gash in my head has closed back up, but it isn’t pretty. The bruises on my face she attributes to the accident, the same way Schroder and Landry did. There is a huge bruise running down the side of my neck,

and she can’t see the bruise across my chest from the seatbelt.

I have cuts all over my hands; the end of the finger bandage is stained with blood.

My mum is in her late sixties but thinks she is in her forties and that I’m still nine years old. Her hair isn’t quite as grey as my neighbour’s, and her glasses aren’t quite as big – but I figure in ten years they’ll be a match.

‘You need to go to a doctor,’ she says.

“I’m fine. I’ve already been checked over.’

‘Doesn’t look like they did a good job.’

She starts to tidy up. I tell her not to bother, but the only

thing she doesn’t bother to do is listen to my requests. Mum tells me how disappointed Bridget would be if she knew what was

happening, not just about the drunk driving but also the way I’ve been treating myself lately. I keep saying “I know’ over and over, but she doesn’t seem to get tired hearing it. After nearly an hour she lets me drive her back home and I keep the car.

“I’m also strapped for cash,’ I say, ‘and I need a new phone.

I hate asking, but can you help me out here?’

‘There’s already some in the glovebox,’ she says. ‘We worry

about you, Theo. More than you think. Are you going to come in and say hello to your Father?’

“I don’t know. I guess that depends on how disapproving he is

that I’m borrowing his car.’

“Then you’d best be on your way’ she says, grinning at me.

She leans over then, and gives me a hug, and for the briefest of moments I feel like everything is going to be okay.

When I get to the library I open the glovebox and find an

envelope with a thousand dollars in cash. She must have dropped into a bank on the way. She knew I didn’t forget to pay the phone bill, that I didn’t pay it because I haven’t worked in weeks. I suddenly feel like turning around and giving it all back – the money and the car – because I don’t deserve anybody to worry

about me. But I don’t. There are too many dead girls, too many dead caretakers and a dead priest, all pressing me forward. Plus somebody out there tried to frame me for murder.

The library is warm and quiet. Plenty of people who live in

different worlds from me are sitting down reading about worlds similar to the one I’m falling into. I find the newspaper sections on the computer and print out all the articles that mention

the missing girls. There are the ones I got from beneath Bruce Alderman’s bed, plus the stories that have been in the papers

since the girls were discovered. I spend the rest of the afternoon re-reading these stories and printing them out. I print out the stories about Bruce Alderman’s suicide and about his Father’s

disappearance too. I end up with a stack of paper dedicated to the dead almost a centimetre thick.

I leave the library and hit five o’clock traffic. SUVs are blocking views at intersections, and not for the first time I figure they’re the reason everybody in this world is going nuts. It sure as hell was my reason. I look at the money my parents gave me, and

the maths is simple – there’s enough here for me to drink my

way out of this and every other problem for the next few weeks.

I could go into a bar – there are several en route – and things would be okay again, at least for a little while.

WWJD?

What would James do? I figure Quentin James would have

pulled over. He’d have slipped inside and let five minutes turn into ten, ten into an hour, an hour into a night. Or maybe if I’d let him live things would be different now. Perhaps he’d have found redemption, or God, or something that would have kept him out

of those bars. I don’t know, and thinking about James kills any desire to go inside. I drive past them all and don’t look back.

chapter thirty-nine

On the way to the morgue I stop in at the store where I bought my last cellphone. It feels like a long time ago. Much longer than four weeks. I spend a hundred and fifty bucks on a cellphone

that has more features than even Gene Roddenberry could have

dreamt of. I ask to get my number transferred over and am told it’ll take an hour or two.

There’s a security officer sitting behind a desk at the entrance to the morgue. I give him my details and he checks my name on

the list. He gives me a visitor’s pass and I attach it to the front of my shirt. He seems friendly enough, which I suppose must mean

he hasn’t spent any time reading the papers or watching the news.

The guy probably gets a big enough dose of reality working the morgue.

As I head down the corridor the temperature drops with every

footstep. I go through the large plastic doors that separate the corridor and offices from the freezer, where all the work is done.

It’s been a month since I was last here too. Before that it was two years. It means my visits are becoming more frequent.

‘Hi, Tate,’ Tracey says, moving over towards me from the

large sets of drawers in which are stored the other people unlucky enough to be here at six o’clock on a Friday night. ‘You just caught me.’

She looks different. Her hair is a little frazzled. She looks paler and tired, more worn down, as though both life and death are

starting to get on top of her.

‘It’s been a rough week,’ she says, as if acknowledging my

thoughts.

‘Yeah. Tell me about it.’

There are empty metal tables with sheets and tools but no

bodies.

“I could really use a drink,’ she says, then pauses, recognising her mistake. ‘Sorry Tate, that was a bit insensitive.’

‘Yeah, so is drinking and driving. How is she?’

‘She’s doing okay. She’s pretty banged up, but she’s out of

the woods. The head trauma was the problem – there was some

internal swelling, but the pressure’s been relieved. She’s going to have some tough months ahead of her, but it could have been

worse, right? You know that more than anybody’

You know that more than anybody. How many people have

said that to me over the last twenty-four hours? ‘So … she’ll get back to a hundred percent?’

‘That’s what they’re saying.’

I move from foot to foot, trying to get some warmth back into

them. My finger with the missing nail is throbbing. The bandage is dark grey and grotty-looking, and hasn’t been changed.

‘Does it hurt?’ she asks.

‘It’s okay’

‘Let me re-dress it for you while we’re talking.’

I follow her through to the office and sit down. She drags

her chair around, pulls on some latex gloves and takes the old bandage off my finger. The gauze has caught a little, blood and pus having set on the outside of it.

‘Have you worked on the priest yet?’

‘Come on, Theo, you know I can’t share any of that with

you.’

‘It’s important.’

“I think you’re forgetting that I’m still pissed at you for stealing Rachel Tyler’s ring.’

“I’m sorry about that.’

‘Oh, well that covers everything then, doesn’t it? As long as

you’re sorry’ She pulls the gauze away, ripping off the scabbing.

‘Aw, Jesus, Tracey.’ I pull my hand back.

She drops the gauze into a bin. “I go to the mat for you by

never mentioning it, and suddenly Landry’s down here this

morning asking me about it. Now I’m the one who’s gonna get

crapped on.’

‘Let me make it up to you.’

‘Give me your hand.’

“No.’

‘Come on, Theo, grow up. Give me your damn hand.’

I reach back over and she starts to clean the wound.

‘Look,’ I say, “I think I’m entitled to some information here.

After all, I’m the one they accused of killing him.’

‘If anything, that entitles you to absolutely no information at all. When was the last time you let a suspect walk down here and ask whatever he wanted about the crime?’

‘This is different.’

“Not to me. Not to anybody. You shouldn’t even be here.’

She cuts off some fresh gauze and places it over my fingertip.

Then she adds some padding. ‘Goddamn it, Tate, if there was

somebody as qualified to take over, I’d probably already have

been suspended.’

‘They know I didn’t do it. Did Landry tell you that?’

‘Yeah. He did. But that still doesn’t change anything.’

I look over my shoulder at the drawers through the office

window. One of them contains Father Julian. Two nights ago

I came close to occupying another one. The throbbing in my

finger grows stronger, and Tracey starts to bandage it.

‘It changes it for me, right? Think of it from my perspective.

The cops know and I know that somebody killed Father Julian

and tried to pin that on me. I think that means I have a stake in this investigation. I think that it means I deserve to be told as !# . .!S

much as possible so I can try to defend myself.’

‘Defend yourself against what? They already know you’re

innocent.’

‘Come on, Tracey You know the score. You know three of

those girls would still be alive if I’d done my job properly two years ago. I want this guy off the street.’

She tapes off the bandage and leans back. ‘People who you

want off the street are never heard from again, Theo. I’m sorry, but I can’t give you anything.’

‘Was the hammer the cause of death?’

“It’s getting late. I’ve got a family to get home to.’

‘Come on, give me something here. Bruce Alderman, his father,

now the priest – they’re dead for a reason. And this person who planted the hammer in my house is probably the same person

who killed all those girls.’

‘Sidney Alderman is dead? How do you know that?’

“I’m guessing, but it makes sense, right? Everything is

related.’

“Not everything,’ Tracey says.

‘What do you mean?’

She sighs, and her shoulders slump as if she’s sick and tired of talking to a ten-year-old.

‘Please, just drop it.’

‘Would you? Come on, Tracey, name me one detective you

know who wouldn’t be trying to do the same thing.’

‘The problem is you’re not a detective. Not any more.’

“I know, but…’

‘Look, one thing, okay? I’m going to tell you one thing, then

I want you to leave.’

‘Okay’

‘And you can’t come back. You promise?’

I’ve heard that line before. ‘What is it?’

‘Sidney and Bruce Alderman. They’re not related. Sidney

Alderman is not Bruce Alderman’s father.’