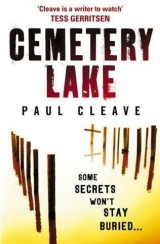

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter eighteen

All the oxygen is sucked out of me. I stare down at the coffin with the silk linings and soft pillow, and the world outside of the grave fades away and goes black. There are crumbs of dirt where my

daughter should have been. The brass handles have pitted, the

glossy sheen of the wood long since gone. There are cracks and dents in the wood. My first reaction is to climb down and make sure with my hands as well as my eyes that Emily isn’t in there.

My second reaction is to scream. Instead I fall back to the third reaction, the one I had two years ago when I got the call about the accident. I drop to my knees and start to weep and try to

convince myself this isn’t really happening.

It should be simple to know which is worse – my wife

missing or my daughter – but suddenly I don’t know. Suddenly

they both seem as bad as each other. I guess the worse of the two is the one that is happening. I’ve dealt with a lot over the years, but never somebody’s dead child being stolen from a graveyard.

Kidnapped. I don’t even know if that’s the term for it.

I have no real idea what to do. No real direction to take. A

dead child is every parent’s worst nightmare. What is it when all the nightmares come true?

I have lost Emily. Again.

Two years ago it had been on a Tuesday. Tuesdays are a nothing day. People don’t make great plans for a Tuesday. They don’t get married. Don’t leave for holiday. They don’t organise house

warmings. But the fact is one in seven people dies on a Tuesday.

One in seven is born. What better day to lose your family? Is

there a worse day? That Tuesday should have been like the others.

I kissed my daughter and my wife on the way out the door, and

the next time I saw them Emily was lying on a metal slab with a sheet tucked up to her neck so I could see her face. Bridget was in a world between life and death, hooked up to machinery and

surrounded by doctors.

Hours earlier they had gone out to see a movie. It was two

o’clock in the afternoon, and Disney was entertaining my daughter on the big screen with animals that could talk and evade capture and do taxes and everything else clever animals can do. It was school holidays. My wife was a teacher, so it was holidays for her too. At quarter to four the movie ended and my wife walked my

daughter outside along with dozens of other parents and children.

They walked around the shopping complex footpath towards her

car. It was ten to four, and already Quentin James was drunk. It was ten to four in the middle of the afternoon, and Quentin James was behind the wheel of his dark blue SUV that he had paid a

four-hundred-dollar fine to get back that morning. He had no

driver’s licence but that didn’t stop him paying the fine; it didn’t stop the courts from handing over the keys. I can only imagine how it happened – bits of imagery I added together with details from eye witnesses. The SUV swerving through the car park. The SUV jumping the curb onto the footpath. My wife and daughter

hearing it, both of them turning towards the sound. Emily’s tiny hand tight inside my wife’s grip. The look on Bridget’s face as she realised there was nothing they could do, that the SUV was going to knock them around like rag dolls.

She pushed Emily out of the way. That’s what they tell me. She did what any mother would do and tried to save her daughter.

Only it wasn’t enough. The four-wheel-drive slammed into them

both; it knocked my wife onto the hood, it rolled my daughter

beneath the wheels, and it broke them. It broke my little girl up inside beyond repair. It did the same to my wife. It did the same to me. And to my parents.

And still Quentin kept driving. He would tell me two weeks

later, when I took him away to a small corner of the world, that he couldn’t even remember running into them. He told me

that it wasn’t him, not really, but the man he became when the booze took over. Therefore I had the wrong man. He was sick,

he said, and it was the sick Quentin who ran over and killed my daughter. The Quentin pleading for his life in front of me wasn’t the man who had killed my girl, at least according to the sober Quentin, but that didn’t matter to me. It was the bullshit plea of a weak and cowardly drunk during one of his few sober moments.

He said he couldn’t remember running them over but that didn’t matter either. I could. And so could witnesses. They told me the impact sounded dull, like heavy suitcases being dropped on the pavement from a second-storey window. They told me my wife

rolled across the hood of the SUV and was thrown hard into

the concrete. They told me my little girl tumbled and bounced

beneath the chassis until she was spat out the end, ejected from between the wheels all twisted and bloody. They tell me my wife and daughter ended up in the same place, side by side on the

pavement. Quentin kept on driving.

Quentin James was caught within an hour. His four-wheel

drive with the bull bars on the front that was never once used off road in the four years he owned it was impounded. It was

kept as evidence. He was charged with manslaughter and reckless driving, but he should have been charged with murder. I never

figured that one out. The guy chose to drive drunk. He chose to do it every single damn day of his life. That means it didn’t come down to fate or bad luck, but down to a conscious choice. That and statistics. It came down to mathematics. It means it had to happen. Put a drunk guy out on the roads every day and he’s

bound to kill somebody. Has to happen, the same way if you keep flipping a coin it has to come up tails.

So for me, manslaughter didn’t cut it. Didn’t come close. He

got released on bail and he tried to get his car back, but for the first time ever they wouldn’t let him have it. They couldn’t – because people were outraged by the accident. They were angry at the system that allowed him to keep going free. So this time the courts weren’t giving his car back, not at least until the trial was over. It was as though the judge finally figured out that giving this guy his car back was like handing Jack the Ripper a scalpel, that in this case it couldn’t all be about revenue gathering. This time James would do time. That was for sure. They’d lock him away

for two years in a cell that was a hell of a lot bigger than the coffin my daughter got locked in.

But everything worked out different. Quentin James never

went to jail. My daughter is no longer in her resting place. The world has gone topsy-turvy and I don’t know what to do. I’m

kneeling in the grass next to a mound of dirt and an empty

coffin. Sidney Alderman has come along and dug up her grave in the same way his son dug up others. He has dug up and torn the stitches from the memories, and the pain of losing my daughter is as strong as it was the day Quentin James stole her from me. James is no longer around to direct my anger towards, but Alderman is, and I’m going to find the son of a bitch.

I stand up. I turn my back on the grave of my little girl. The sky has cleared even more and it looks like it could actually turn into a pretty good day. As good as it can get, weather wise. As bad as it can get in every other way. I start my car and drive to Alderman’s house. I’m tempted to drive right into it, just hit the sucker at a hundred kilometres an hour and shred the weatherboards and

plasterboard to pieces. Instead I bring the car to a fast stop up his driveway, skidding the shingle out in all directions and creating a thin cloud of dirt that drifts past the front of the car and towards the house. I get out and slam the door, wishing I had access to the gun the caretaker’s son used on himself. All I have access to is my anger – it should be enough. I think in the end anger will beat out sorrow on any given day. Even on a Tuesday.

chapter nineteen

The house still smells of alcohol and the air is damp. The furniture bugs me in a way that furniture shouldn’t be able to do. I want to set fire to the place. Pour gasoline all over the walls and floors and the clawed-up lounge suite and turn the whole fucking lot to ash.

Preferably with Sidney Alderman in here. Preferably with him

gagged and tied and very aware of what is going on.

Only he isn’t here. He’s off somewhere with my daughter

doing God knows what. Burying her somewhere, I guess. Or

dumping her in another lake or a river or an ocean.

The photo albums have all disappeared. It tells me Alderman

knew I was here and was figuring I’d come back. I start looking through the house again. I go through his drawers and his

cupboards but I don’t find anything useful, because anything

useful the police will already have found. I pull everything apart.

I dump files and rubbish and books on the floor as I go, but

there’s nothing. I push everything aside roughly, making a mess, enjoying the process of damage. It’s not enough to take away any of the pain, but for the short term it will have to do.

I head back out to my car and grab the charger for my cellphone.

I plug it into a socket next to Alderman’s toaster and watch as my

phone starts to power up. I leave it charging while I check the bedrooms. Bruce Alderman said the proof was under his bed, but he may as well have said that a year ago. The two bedrooms in use have completely distinct personalities. It’s obvious to see which one belongs to the old man and which to the son. The father’s

bedroom has wedding pictures up on the wall. It has underwear

scattered across the floor. It has a busted-up clock radio lying in an old pile of newspapers. There are booze bottles stacked along the windowsills. The curtains are grimy and old. The bed hasn’t been made; the pillow case is blackened in the middle from sweat and dirt and whatever product the old man once ran through his hair. The loss of his wife was so hard on the guy that he never recovered. He lost control of his own life, and ten years later he’s still losing control.

I walk into Bruce’s room. It’s like walking into a cheap motel room that prides itself on doing the best with what it has. The bed has been made. Books are stacked almost neatly on the bedside

table. Three pairs of shoes are lined up beneath the window.

Sneakers, dress shoes, work shoes. I look under the bed. Whatever evidence was there has gone. I check the closet and go through the pockets of whatever is hanging there. Then the drawers. I’m not tidier than the police. I pull the drawers all the way out and check beneath them for any taped-up envelopes or photographs he has

hidden there. But there’s nothing. I pick up and riffle through the books. Nothing falls out of them. I check the tides on the spines.

He read a mixture of fantasy and sci-fi, but there don’t appear to be any serial killer novels or FBI handbooks about how to avoid getting caught. There are shoeboxes stacked in his wardrobe that are full of mostly junk – a Rubik’s cube, small plastic Smurfs, old coins, even some old shoes.

I check under the bed again, just in case, but there’s nothing there at all. Just dust. Which doesn’t make sense. People always squirrel crap away under their beds. Bruce Alderman has nothing, except the thick dust, and there are no clean patches where items have been removed. I drag the bed out from the wall.

The corner of the carpet is easy to pull up, because it’s been pulled up before. Plenty of times, I’m guessing, which is why

he never stored anything under here. There are four A4-sized

envelopes side by side, each one very thin. I pull the carpet all the way back, but there is nothing else.

I spill the contents of the first envelope onto the bed. I open the other three. They’re all the same. Different articles cut from different newspapers covering different women. Nearly twenty of them, a separate envelope for each of the four girls. The dates begin two years ago and end two days ago. There are articles for the three girls I’ve identified, and for the fourth one I haven’t.

Her name is Jennifer Bowen. I now know all four names.

Four women missing from Christchurch but the world kept

on spinning. Nobody took a moment to figure out what in the

hell was going on. Four women from four different backgrounds, all of them young – born within five years of each other – and no one made the connection. They didn’t make it because they

didn’t want to. The articles are full of suggestions. The girls were wayward. They were runaways. The articles about Rachel Tyler

suggest she fought with her boyfriend. They hint the boyfriend could have been responsible. They mention the dead grandmother and lead a path for the reader to believe she could have run away because she was upset. They suggest lots of things and confirm nothing, just throwing out ideas in the hope that if they cast a wide enough net they might cover something correctly.

I slide all the articles back into the one envelope. They don’t do much to back Bruce Alderman’s claim that he didn’t kill these women. All four of them could have died in here. And Emily?

Did Bruce’s father bring Emily back here before driving her away?

Did he carry her corpse and rest her on the couch while he packed some things together? No. He would have dumped her in the

boot of his car. He wouldn’t have been careful about it.

I take my phone and step outside. The lake, the church, the

land of the dead – none of it can be seen from anywhere on this property, not unless I was to take the ladder out of the shed and climb up on the roof or scale the fence. I do the latter.

The property backs onto the cemetery. The police, the

excavations, the canvas tents and crime scene techies, these things don’t reach Alderman’s house. I can’t imagine what it would have been like to grow up in a house where the view over your back

fence was of trees and granite headstones. Surely it had to be disturbing. Surely it couldn’t have been healthy. I wonder if this environment is what made Bruce Alderman a sick man. Whether

it made Sidney Alderman a sick man. Or whether it was the loss of their mother and wife that made them so.

chapter twenty

I’m half expecting to find my house has been set on fire when

I get home. Or the windows broken. Or, at the very least, to

have ‘murderer’ spray-painted across the garage door and fence.

I pull into the driveway, stand next to my car and stare up and down the street. I’m looking for Sidney Alderman, but he isn’t here. Nobody is. Not even Casey Horwell. All of my neighbours

are off doing whatever it is that neighbours do. Mow lawns. Pull weeds. Cook food and watch TV None of them are trying to

figure out where their dead children are. I’m careful as I make my way inside. I had a gun pulled on me last night, and hours later a microphone, and I’m not eager to make either mistake twice.

I plug my cellphone back into the charger, then I bring the

computer in from the car and set it up on the dining-room table.

Bridget would not be pleased. I use the Christchurch Library

database of newspapers to find more articles related to the ones Bruce clipped. I take on board as much as I can from them, and from the Missing Persons reports, and as much as I can about

their lives and about their deaths – not that any of the articles say they are dead. But they sure read as though the journalists were all betting heavily on it. I print out a photo of the fourth girl, then

line the pictures up in a row. Their killer certainly had a fondness for a specific type of girl.

I spend two hours reading all about the missing, and it’s hard, because my mind keeps returning to Alderman and Emily.

I search the obituaries for the weeks prior to the girls’ deaths, looking for the same last names to see if there was a reason for any or all of them to attend a funeral. I come up with nothing. It’s not a busted lead at this stage because it could be they still went to funerals of people outside their families, or family members with different last names. The only way to know for sure is to start making some phone calls, but right now talking to these dead

girls’ families is the last thing I feel like doing.

I set the whiteboard up, propping it up on a chair and leaning the top against a wall. I’ve got nothing but a permanent marker to draw with, but go ahead anyway, starting with a timeline. I figure that Henry Martins would have been buried two days after he died. If I add those days on to the date of his death, it matches up nicely. Henry died on a Tuesday and was buried on a Thursday.

Rachel was last seen Thursday morning, and was reported missing by her parents the following Tuesday. But then I add the other missing girls to the timeline, and find that the dates between disappearances are not that even. The first two girls went missing within a month of each other, then there was another eighteen

months until the third went missing, and the last was less than a week ago. It doesn’t suggest that the murderer is escalating or slowing, and I’m not sure what that in itself suggests. Guys like this tend to start killing more often as the need overtakes the desire. Or there is something in their life that triggers the impulse to kill. I look at the timeline and wonder what made this guy kill at these particular moments. Was it simply that the right type of girl came into his localised view of the world? Or did he go hunting for women to fit his type? There has to be more to it – I write Prison? on the board, wondering if the killer could have been in jail for eighteen months. It’s common for serial killers to get arrested for an unrelated crime.

I go through the obituaries again, hunting out those who died

in the days leading up to the girls’ disappearances. Two of these people are no longer in their coffins, and are lying on morgue tables in different stages of decay, their bodies waterlogged and bloated or decayed.

I look at the timeline. I think about Emily. I think about

Bruce Alderman and about his father. Then I think about where I was two years ago and the difference I could have made. That was my chance to save these girls. Maybe Landry was right, and I am fucking everything up. I don’t know. All I know is that I have to find Emily.

My cellphone finally has a full charge. I go through the

memory of incoming calls, put Landry’s number into the address book function, and then dial his phone. He picks it up after half a ring.

“I was about to call you,’ he says. ‘Your name just keeps on

popping up. You need to stay the hell away from my

investigation.’

“I can help.’

‘Help? You seen the news lately?’

‘Look, that isn’t…’

“I don’t mean that fuck-up you made last night. I mean the

new one you’ve got on your hands today’

“I haven’t heard. What have I done now?’

‘Jesus, man, you must’ve really fucked off this Horwell chick at some point. What’d you do, sleep with her?’

‘Yeah, good one, Landry’

‘Turns out when people don’t like you, they really don’t like

you. I guess I’m starting to see why’

‘There a point here?’

‘She interviewed Alderman this morning. Had to be sometime

after he hit the bar, but looking at him it couldn’t have been long after. Didn’t seem to have many drinks under his belt.’

And?’

And it wasn’t good. It’s like she saw this fire burning inside him and just started throwing on more fuel. Hadn’t been for all those angles and splatter trajectories, even I’d be thinking you

were guilty. Anyway whatever anger he had about you before,

you can double it and double that again. Just keep an eye out.

And do us all a favour, huh? Stay indoors and turn off your phone until we get this thing nailed down. When it goes to court, we’re going to be looking at some defence lawyer pointing the finger at you and saying …’

‘Yeah – we covered this already’

‘Then why don’t I feel assured?’

I look down at the photographs and the newspaper clippings.

‘Look, Landry, I got something for you. You want to hear it or not?’

‘That depends on how you got what you got. Is this going to

backfire? If you’ve got anything and you’ve obtained it illegally, I don’t want to know about it, right? Otherwise it’ll blow up in our faces.’

‘Okay’

He doesn’t say anything and I don’t add anything else, and he

reads my silence accurately.

‘Jesus, Tate, you’re fucking unbelievable.’

‘You want the names of the other girls or not?’

‘Do me a favour and don’t tell me. There’s a hodine for

information. Ring it anonymously and give it to them, okay?

Ring from a payphone or something. Anything you give me from

an illegal search is poison. Fuck, Tate, you know that.’

‘I’m no longer a cop. Those same rules don’t apply’

‘Yeah, and this serial killer’s defence lawyer you don’t want me to keep reminding you about is going to …’

‘Right. No problem. So you don’t want my help.’

‘Help? Is that what you think you’ve been doing? I gotta go.

Make sure you …’

“I got something else.’

‘What? Jesus, Tate. You’re going to give me a fucking heart

attack.’

‘Look, this is something good. It’s something you can say you

came up with on your own, so you don’t have to …’

‘Come on, I know how to do my goddamn job.’

‘Rachel Tyler, before she died, visited Woodland Estates. Her

grandmother died. It’s the same cemetery’

Landry doesn’t answer. I can tell he hadn’t made this

connection.

I press on. “I think the others might have been there too.

I think that’s the connection. That’s what drew them to the

killer.’

‘You got anything to back that up?’

“Not yet. But I’m …’

“No buts, Tate. You’re off this thing. Go ahead and make that

call to the hodine, give us those names. Do it now.’

He hangs up without me telling him Alderman has my daughter.

And thats OK – I want to deal with Alderman myself.

The phone call I’m going to make will take most of their

legwork out of play. It’ll mean the contents of the other two coffins are no longer up for grabs. But that call can wait. First I’m going to find Sidney Alderman and do what it takes to get my daughter back, and that’s something I don’t need Landry’s help for.