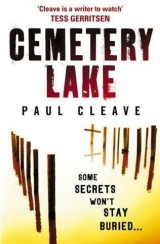

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

chapter eleven

Too much training and not enough experience. That’s my

problem. Plus the training never detailed anything like this. It was more a general thing, like a commonsense warning. If a gun is pointed at you in close proximity, stay calm. Try to talk your way out of it. It’s advice I would’ve figured out even if I’d never learned it.

‘D-d-don’t try anything,’ Bruce says, so I don’t. I don’t fight for the gun. I don’t open the door and try to run. Don’t do any of this because it’d be pointless, unless the point was to get shot.

Instead I slowly adjust my body so I can turn my head and

face him. The gun looks huge, but only because of the viewing

angle and I’m not the one holding it. There are two hands on

the handle. Both are shaking. A finger is wrapped around the

trigger.

It strains my eyes to keep the barrel in focus, but I keep them strained. If Bruce Alderman wanted me dead, he’d have done it

already, but I feel as though if I take my eyes off the barrel I’m going to die.

‘What do you want?’

“I d-d-don’t know,’ he says, and his answer is a problem. If he doesn’t know, that means he has no plan, and that makes him far more dangerous, and it means maybe he is planning on shooting

me. Maybe that’s where his plan is taking him.

His hands keep shaking, the gun rising and falling with minute motions.

‘You must want me for something,’ I say. ‘Probably to tell me

something. Right? To tell me you had nothing to do with the

dead girl we found?’

‘Why were you t-talking to my f-f-father?’

‘I was looking for you.’

‘You s-started this,’ Bruce says. ‘If it hadn’t been for you,

everything w-w-would be okay. It would be okay’

No, it wouldn’t be okay. Hasn’t been okay for Rachel Tyler for some time now.

‘Why is that?’ I ask.

‘What did my father say?’

‘You’re dad’s a real affable guy. He had plenty to say’

He pushes himself back into the seat but keeps the gun levelled at my head.

‘You think I k-k-killed those girls?’

I don’t answer. I look at Sidney Alderman’s house and wonder

what he’s doing right now. Could be Sidney knew his son was

out here waiting for me and was putting on a show, his own little performance of misdirection. Could be he didn’t know. It’s not like they could have anticipated my coming here. Bruce must

have been here all along, or he followed me from the church.

‘Please, “I … I need you to drive away from here.’

I turn back towards him and stare at the gun barrel. ‘Drive?

Where to?’

“I don’t – I don’t know’

‘I’m not a taxi service. I’m not going to take you somewhere

where you can kill me in private. You want to do that, you do

it here, and maybe your old man can help you dispose of my

body. Or you might luck out and the cops will hear the gunshot.

They’re not that far away.’

‘Is that w-what you want?’ he asks, pushing the gun forward

a few more inches. ‘You think I w-won’t do it? You think I’ve got something to lose by doing it?’

‘I don’t think that’s your plan,’ I say, trying to sound calm, ‘and I don’t think you’re going to pull that trigger. You’d have done it already. You want to tell me something. Maybe you want to confess. Maybe you want to tell me all about it before putting a bullet in my chest.’ His hands start to shake a little more. I figure I’m only a few shakes away from getting the back of my

head splashed on the windscreen. ‘But you don’t want that to

happen here.’

‘Maybe you’re wrong.’

I think about my wife. If I’m wrong, I won’t be seeing her

again. If I’m wrong – and if I’m lucky – maybe I’ll be seeing my daughter. Only problem there is I don’t believe in an afterlife.

I think of Bridget, already alone and about to become even more so. Except that she’d stare out the window as my death made the newspapers and TV and she’d never feel the loss.

‘So where do you want to go?’

Away from here. N-now.’

I manage to shift my eyes from the barrel to his pale face.

His features have sunken since the afternoon, as if the bubble of paranoia holding them in place is slowly deflating. His eyes dart nervously back and forth, unable to fix on any one thing for more than a fraction of a second, like he’s hyped up on drugs. There are beads of sweat dangerously close to rolling into his reddened eyes. Behind him, further up the road, dead people are being

found in other dead people’s places. I look back at the gun, then at his eyes. Back and forth, back and forth, his eyes are looking for something – whether for help or for the demons that have

chased him his entire life, who knows? Could be he’s looking for his caretaker father to take care of this.

‘Please,’ he repeats, more begging than demanding.

I turn around, and it’s hard to keep looking ahead with the

weight of the gun trying to pull my eyes back. I swing the car around, wondering if the old man is watching any of this from his filth-covered windows, or even if he can see through them. In the rear-view mirror the house in the glow of my brake lights looks like it’s set on Mars. I head past the cemetery, past the dozen or so people helping the dead and ignoring, for the time being, the living. I pass the large iron gates that look like they were sculpted two thousand years ago to guard some Greek mythological

fortress. I pass the church parked back from the road. I’m not sure what Bruce Alderman’s plans are, and I wish at least he was.

I pick a direction and stick to it.

We stop at the first intersection behind a beaten-up pickup

with a sun-faded bumper sticker on the back saying Oral Me. ‘Why don’t you tell me what’s going on.’

The caretaker doesn’t answer.

“I can help you.’

‘Help me?’

‘You must want something.’

“Nobody can give me what I want.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I know. It’s impossible. Unless you can turn back time. Can

you? Can you make the last ten years disappear?’

His stutter has gone and I suspect that’s because we’re away

from the cemetery. Or, more accurately, away from his dad. He

sounds like he did this afternoon when I spoke to him briefly

before the digger came along and unearthed all these questions.

He also sounds as if his question is genuine, as if he’s holding out hope that maybe I can make the impossible happen. I hope it’s

not part of his plan.

‘You’re not the only one who wishes they could turn back

time. All I can do is listen to what you have to say. And then I can give you some options. You want to tell me why you killed

Rachel Tyler?’

‘You know her name?’ he says, instead of denying it like an

innocent man would.

‘I’m a quick learner.’

‘That’s why you’re looking for me, because you think I killed

those girls.’

‘You want me to think otherwise?’

‘I never killed anybody,’ he says.

“huh. Is that why you were in such a hurry to leave this

afternoon that you stole the truck? Is that why you’ve got a gun to my head? Doesn’t seem like the path an innocent man would

be taking.’

‘You don’t know that,’ he says. ‘Can’t know that. You’d be

doing the same thing.’

“I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t be.’

The intersection clears and we carry on, getting hooked into

the flow of other traffic.

‘You have an office, right?’

‘Why?’

‘You must do. All Pis have offices.’

“I don’t know all the Pis in this world. Half of them could be working out of their cars for all I know. Or their houses.’

He pushes the barrel into my neck. He seems to be getting

more and more confident. Only it’s a sliding-scale type of

confidence. He’s more confident, perhaps, than a six-year-old girl walking through a cemetery on a dare. Not as confident as a guy holding up a bank.

‘Will we be alone there?’ he asks.

‘Yes.’ I change lanes and start altering my course. ‘But the

coffee isn’t anything to write home about.’

He doesn’t offer any further conversation as we drive, and

I decide against asking for any. I let him sit in silence, allowing him time to figure something out.

I turn into the car park behind my building, and I take my

spot, which in the past I’ve had people towed out of.

‘Now what?’

“Is there a security guard on duty?’

‘This isn’t a bank.’

He stays out of reach as we walk to the back entrance, but comes in close when we get there. There’s a swipe pad mounted on the wall – it’s all very low-tech – and I slip a card through the reader. There’s a mechanical sound of metal disengaging from metal, then I push the door open. He follows closely behind me, and my first opportunity of getting rid of him by slamming the door on his face is lost.

‘How many floors?’ he asks.

‘How many floors what?’

‘What floor are you on?’

‘The eighth.’

‘Let’s take the stairs.’

I’ve already pushed the button on the elevator and the doors

have opened. ‘This is much quicker.’

‘Too confined.’

‘You claustrophobic?’

‘Where are they?’

‘This way.’

I lead him into the stairwell. It’s cold and our footfalls echo as we take the stairs two at a time for the first four floors, then one at a time for the remainder. When we reach the eighth floor, we’re both breathing heavily. We see nobody as we move down

the corridor. There are potted plants full of crisp green leaves and no brown ones, oil paintings that don’t represent anything, just colours and shapes thrown together in appealing ways.

We reach my office. I step in. Bruce reaches behind him and

shuts the door.

‘Sit down and keep your hands on the desk,’ he says.

I do as he asks, resting my palms either side of the watch

I took earlier. Bruce sits on the other side of the desk as if he were a client.

‘How much do you know?’ he asks.

‘About what?’

‘Don’t be like this,’ he says, slapping one hand on the side of his chair while keeping the other on the gun. Steady now, as if all the nerves are gone. As if being away from the cemetery has cured him. As if over the last fifteen minutes all the confusion, all the fear, all the guilt have somehow lined up, found a way to get along, and formed a brilliant idea about what to do next.

‘Okay, here’s what I know,’ I say. ‘From the moment you

found out we were digging up Henry Martins, you were nervous.

You hung around despite that, but as soon as the bodies started coming up to the surface of the lake you bolted. Things were

inevitable then. We were all on the same train ride. In the car a while ago you were surprised I’d identified the girl. Rachel Tyler.

You asked if I thought you’d killed the girls. Not people, but girls. That means you already know that when the other bodies

are identified, and the matching coffins dug up, there are going to be women in there. The only way you could know that was if

you put them there.’

He doesn’t answer. Just stares at me, his hand shaking a little, his options racing behind his jittery eyes. I hope he’s not coming back time and time to the one where he pulls the trigger. Maybe that was his plan all along, and he’s had it from the moment he climbed into my car. He partners up his free hand with the other one to steady the gun.

‘What do you want from me, Bruce?’ I lean back, keeping my

arms out so my hands don’t leave the table. ‘Just tell me.’

‘I need a cigarette,’ he says, and reaches into his pocket.

“I have a No Smoking rule in here,’ I say, and when he pulls his hand back from his pocket it’s empty. He doesn’t complain.

‘I’ve never killed anybody’ he says, after a few seconds of

staring down at his shaking hands, one of which is wrapped tightly around the gun. “I know you think different, but it’s the truth.

I have proof. It’s underneath my bed. I could take you there. You could talk to my father. He knows the truth.’

‘Uh huh.’

‘But you wouldn’t let me take you there, would you?’

‘No.’

‘You don’t believe me at all, do you?’

‘Why don’t you give me a few more details first?’

‘There’s no point. You’ll never believe me. And I knew you

wouldn’t.’

‘Then why bring me back here? Why go through all of this?’

“I didn’t have anything to do with them dying. Nothing. But

I buried them – I had to. The girls, they deserved that. And

now,’ he says, ‘now their ghosts will leave me alone, and you, you will take me seriously’ My heart races as he twists the gun and jams the barrel beneath his chin. It’s almost as frightening as having it pointed at me.

‘Wait, wait,’ I say, and my instinct is to reach out to stop

him, but I keep my hands flat on the table. ‘Listen to me, listen, Bruce.’

He relaxes the gun for a moment, looking at me as if I must be an idiot not to understand him, but it’s just enough of a moment to make me believe there’s a chance neither of us has to die here.

Not much of a chance, not long enough of a moment.

‘Why did you take the bodies out of the graves? What did

these girls deserve?’

For a moment he looks confused, as if he can’t find the right

words, then suddenly his face becomes calm and relaxed as some perfect clarity washes over him, and I know it’s the clarity of a man who has made peace with his decision, and that there is

nothing I can say or do to avoid his next step.

‘For dignity,’ he says, ‘they deserved the dignity’

The gunshot rings in my ears. I smell cordite and burning

flesh long after the pink mist settles, long after pieces of bone and brain are buried into the ceiling above him.

chapter twelve

It’s a life moment. One of those snapshots of time that never

leave you, never seem to fade away. In fact it’s the exact opposite – the colours, the imagery, the detail, they don’t dilute, they grow stronger, clearer; the moment becomes more powerful over

the years while others slowly disappear. The smell – the smell of cooking flesh, the coppery smell of blood, the gunpowder, the

stench as his bowels let go, the sweat. The air tastes hot, it dries out my mouth and makes my tongue stick to its roof. All I hear is a ringing sound that seems as though it will never diminish, as if it too will only grow more powerful.

It’s a life moment. I sit still, I stare ahead, I take it all in.

I don’t know if there are others in the building. Don’t know if the gunshot has already been reported. Blood has formed thick

splotches on the ceiling. They seem to hang there, motionless, unaffected by the gravity. Bruce Alderman’s body also seems to hang there, the hand still on the gun, the gun still pressed into his neck. The front of his shirt is clean, not a speck of blood on it.

His hair is messed up, the bullet forming a volcano shape in the roof of his skull. And still he sits there, as I sit there, motionless, staring at each other, a life moment for me, a death moment for him. Time has paused, as if in snapshot.

Then it begins again. His hand, still gripping the gun, falls

away. It hits the top of his thigh, slides into the arm of the chair; the gun clicks against it and falls onto the carpet. His head drops down, his chin hits his chest; the gunshot hole in his skull is like an eye staring at me, the blood falling through it, giving the impression it’s winking at me. Blood-matted hair falls into place and blocks the view. Blood pools on his shirt. It starts to pull away from the ceiling, droplets that form stalactites before breaking away and raining down. They pad softly into the carpet, make small thudding noises on the fronts of his legs, the back of his neck, the top of his head. It drops onto my shoulders, onto my arms, onto my hands that are still on the desk for him to see.

He stays slumped there, this dead weight in my office chair, then slowly he tips forward, he gains momentum, then his forehead

cracks heavily into the edge of the desk, jarring his head upright as his body falls, keeping him balanced for a moment longer, the back of his head almost touching his shoulders, his face exposed and his empty eyes staring at me, before he continues down to

the ground where he lies in a clump that five seconds ago was a person but is a person no more. He lies on the gun, and still I sit here, watching, waiting: perhaps someone will come along and

tell me that this is what I get for following up a line of questioning into an investigation that isn’t even mine.

The pink mist slowly settles; the smell of the gunshot starts to fade, replaced by urine and shit; and the ringing in my ears slowly dulls to a shrilling noise.

I stand up slowly, as if any sudden movement might cause him

to pick the gun back up and try prefixing his suicide with the word ‘murder’. I move around my desk to the body, careful not to step in any blood. I think of his last words. They deserved the dignity. He wanted me to take him seriously, and he succeeded. Only problem is I still don’t believe he’s innocent. Shooting himself in my office isn’t the action required to prove innocence over guilt; if anything, it helps suggest insanity over sanity. I’d have told him this if I’d been given the chance.

I crouch down and put a hand on his shoulder. Without rolling

him, barely without touching him, I go through his pockets.

There is a small envelope that has my name written on it, only he’s spelt it wrong. In the bottom of the envelope is a small key.

I’m about to sit it up on my desk when I see the blood mist has coated the surface. I fold the envelope in half and tuck it into my pocket. I go through the rest of his pockets. I find car keys and a wallet; I find tissues, two packets of antacids, a broken pencil and one of my business cards. I leave them where they are.

I use my cellphone to call the police because my office phone is covered in blood. I ask for Detective Schroder but get transferred through to Detective Inspector Landry. I’d rather not talk to him, but I’m not running high on options. I tell him the situation as if giving just any old police report. Before I finish I ask him to bring coffee.

‘Jesus, Tate, this isn’t my first homicide,’ he says.

‘You mean suicide.’

‘Yeah. Whatever.’ He hangs up.

I sit on the ground out in the corridor, putting a cushion

between me and the wall so as to not stain it with the blood

splatter on my jacket, and lean back. I think of what Bruce told me. Why kill yourself if you’re not admitting any guilt? How

could you possibly believe he buried those girls but had nothing to do with their deaths?

I pull the envelope out of my pocket. The key looks a little

different from others I’ve seen, and I can’t identify it. There are no marks on it, no numbers, no letters. It could be for a house, a lockbox, a safe, a boat – could be anything. It’s just one more item that I’ve taken from somebody today. The ring is still in my pocket, and the wristwatch is still on my desk. I head back into my office and slip it into a plastic bag before dropping it into my pocket. This whole area is a crime scene now and I don’t need

awkward questions.

I’m still in my office when I hear them arriving. The elevator pings, the doors open, and half a dozen police, including Landry, spill into the corridor. Soon there will be others as they come to

question and photograph and document and study. The cemetery

crime scene was taken away from me, but this one is mine.

I stand by the doorway and watch. I have worked with most

of these men and women in the past, but they look at me as if I’m a stranger. Their greetings are curt, and I am told to step into the corridor and wait.

chapter thirteen

The night drags on. My office is quarantined from me, and from the rest of the world, by yellow boundary tape with black lettering.

Forensic guys dressed in white nylon overalls move slowly around inside, searching every square centimetre in case the vital clue is a microscopic one. Nobody asks to search me, but my hands are

tested for gunshot residue and my jacket is taken from me because of the blood dust that has settled on it. I’m not concerned at all, because the evidence will show that the shooting happened exactly as I said it did. It can’t go any other way. They can’t come back to me tomorrow and say they’ve weighed it all up and their conclusion is I put the gun into his chin and pulled the trigger.

Still, it’s a clear-cut case of suicide that can’t be that clear because of the time they’re taking to studying the angles and

blood patterns. At least that’s how it feels. They’re taking this long to deal with it because they’re dealing with me. They don’t trust me the same way they trusted me when I was one of them.

As an outsider I fall within the scope of their suspicions, and for this I only have myself to blame. I was a different man two years ago. A very different man.

Their questions begin to repeat after a while. The phrasing

alters somewhat, but they’re only variations of the same theme – one that fast gets tiring, and one which seems to suggest there is a degree of blame here that is mine. Only there isn’t. I didn’t force the caretaker into my car. Didn’t force him to come back here. Didn’t force him to shed brain and bone matter across my furniture.

In the end I’m told to go home. I’m not sure how happy I am

to do that, but I’m not sure what the alternative is either. Hang around and watch, I guess, though there isn’t much to watch. Just a bunch of guys doing the kind of tedious work that guys like me don’t have the patience for. If it was daytime there’d be a crowd of onlookers tripping over each other to sneak a peek at the corpse, but I’ve already sneaked a peek, and more – I stole from it.

‘One last thing,’ Landry calls out as I make my way to the

stairwell.

I turn around but keep my hand on the stairwell door. Landry

isn’t one of my biggest fans. There was a time when we were

rather alike, but his life became his work while I did what I could to keep a balance. He’s the same age as me, but he hasn’t aged very well in the two years since I’ve seen him. He doesn’t look good at all. He smells of cigarette smoke and coffee.

‘What did you take?’ he asks.

‘What?’

‘Off your desk. There’s three clear spots. All that misted blood, except for three places. Two are from your hands. Which is a

good thing, because it shows where you were when he pulled the trigger. But there’s something else. A much smaller patch.’

‘My keys.’

‘Doesn’t look like you took keys.’

‘There was so much going on. I don’t know. Maybe it was my

phone.’

‘Didn’t look like a phone. If I was to search you, I wouldn’t

find anything else?’

‘What’s your point, Landry?’

“No point. Just curious as to what would be important enough

for you to steal from a crime scene.’

‘I’m not stealing anything, and anyway it’s my office. Everything in there belongs to me.’

“Not everything,’ he says, and he looks back towards my office where the body of Bruce Alderman is being carried out in a dark canvas bag.

Outside, it’s drizzling again. It’s almost two in the morning. My car is still damp inside, but at least there’s no one in the back holding a gun. I drape one of the ambulance blankets over the

driver’s seat to protect it from any blood still on my clothes, then begin the drive home. The hookers and the homeless stare at me as I pass. I could be their salvation, their next meal, their next drink, their next score.

My house isn’t anything flash, merely one of many placed

slap-bang in the middle of suburbia. People live here, they spend their lives here, they make little people and pay big mortgages, and supposedly, supposedly, if they play by the rules then nothing bad happens to them. The problem is that tonight there is a van parked outside, blocking the entranceway, so I can’t just drive into the garage and walk into the house and ignore it. I pull up behind it and climb out, way too tired for any kind of confrontation.

Immediately the doors to the van open. A spotlight comes on,

a man with a camera resting on his shoulder circles around from my right, and a woman with shoulder-length hair appears on my

left. The bright light accentuates her heavy make-up.

“No comment,’ I say before the cameraman can settle into a

comfortable position and the reporter can push the microphone

into my face.

‘Casey Horwell,’ she says, ‘TVNZ news, just a few quick

questions.’

‘No comment,’ I say, ‘and can you move your van? You’re

blocking my driveway’

‘We have a report that Bruce Alderman, the suspect in the

Burial Murders case, was killed tonight in your office.’

I wonder how long it took them to come up with a name

for the case – the Burial Murders) – or whether tomorrow

somebody will have come up with a better one. Casey Horwell

pushes the microphone closer to my face. I recognise her from

the news. Her career took a slide a year ago when she released information she should never have had, along with her own spin on what it meant, and ultimately compromised an investigation.

It resulted in an innocent man being found guilty in the court of public opinion for the rape of a young child. The night the segment aired, the man’s house was burned down with him inside it. He survived with third-degree burns, but his girlfriend didn’t.

I guess tonight Horwell is trying to pick her career back up.

“No comment,’ I say.

‘That’s not going to get you far,’ she says.

‘You need to move your van.’

‘Can you tell us about your involvement today?’

‘No.’

‘You’re no longer on the force. Why were you at the

cemetery?’

“No comment.’

‘Bruce Alderman was killed four hours ago, and yet here you

are, coming home. Why is that?’

I almost tell her that he wasn’t killed, that he killed himself and there’s a difference, a very big difference.

‘How is it you still get cases?’ she asks. ‘Especially these types.

I was led to believe everybody on the force hated you.’

“I still have a few friends in the department,’ I say. ‘They do what they can to help.’

She smiles and I’m not sure why. ‘Is there anything else you

would like to add?’

‘No.’

‘It’s been a long day, I imagine.’

‘It has been.’

‘It’s been a long day for everybody. I guess it must have been hard on you.’

‘Can you move your van now?’

‘Of course. Thank you for your time, Detect… I mean, Mr

Tate.’

The light on the camera switches off. Casey Horwell looks at

me for a few more seconds, that same smile still on her face, then she turns away and climbs into the van. A few seconds later it pulls away. I get back into my car and park it in the driveway, too tired to put it in the garage.

My house has three bedrooms but only one of them gets used.

My daughter’s bedroom is still set up as if one day she’s going to return home, and I’m not exactly sure how healthy that is and I’m not exactly sure I care to know. If my wife were here maybe she’d have made a decision to change that, but she isn’t. It’s just like Patricia Tyler keeping a room for her daughter. Snapshots of time. It seems to be what life is about.

I put a CD on the stereo, grab a beer and go out onto the

deck, pushing play on my answering machine on the way. It’s

my mother. She’s calling to see how the rest of my day went, and to ask about what happened. I make a mental note to call her

tomorrow.

The night has warmed up a little, and I sit on the deckchair

in the misty rain and stare up at the night, listening to the music as the beer helps calm my nerves. I’d sit out here sometimes

with Bridget after Emily was asleep. It’s sheltered from the wind when it’s cold, but when the wind is warm it sweeps in from the opposite direction and onto the deck. I’d slowly drink a beer and she’d slowly drink a wine and we’d talk about our day. I always felt as though I could tell her anything, but there were cases I couldn’t bring home. They would stay in my mind but I didn’t want them in hers. They were a part of my life and I didn’t want them to intrude on hers. We’d talk about our pasts and about

our future; we had plans to move into a bigger house, we were

debating whether to have more children. We would sit out here

and laugh, we would make plans, we would argue.

The rain drifts away and the sky clears a little; a gap appears in the cloud cover, and for a moment there’s a quarter moon up there, it throws around enough pale light so that when I look at my watch I can see the night is slipping further away. Emily’s cat, a ginger torn named Daxter, comes through the sliding door and jumps up on my lap. He starts purring while I scratch him

under his chin. He was only six months old when Emily died, and any question as to whether cats can remember people has been

answered by the fact that the only place he ever sleeps is on her bed, and that sometimes he has the same look in his eyes my wife has – as if he’s looking for something that isn’t there any more.

I finish the beer and head back inside. I refill Daxter’s bowls with food and water, and he seems grateful enough. I walk past my daughter’s bedroom but don’t go in. There isn’t any point.

I take a shower and I think about Rachel Tyler, but I try hard not to think about what her final hour was like. I try to envision a scenario in which Bruce the dead caretaker is innocent, but can’t seem to come up with much. Then I think about Casey Horwell,

and can’t help but wonder if there is any truth in what she said about everybody hating me.

Daxter is asleep on Emily’s bed when I finally hit the sack.

I lie in the darkness, thinking about my dead family and the man who made them that way. I wish that in this average house in this average street nothing bad had ever happened, but it’s already too late.