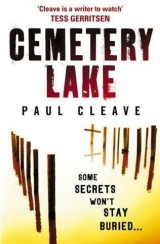

Текст книги "Cemetery Lake"

Автор книги: Paul Cleave

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

“I don’t know. I mean, if this isn’t a result of nature and they were dug up, they had to be dug up for something, didn’t they?

Have they been used for anything? Experimented on? What

about jewellery? Are any of them wearing … ?’

‘The hands of the male are skeletal, so nothing there; but our Woman, she’s wearing rings and she’s got a necklace. You can rule out grave robbery.’

Grave robbery. I feel as though I’ve slipped back into a Sherlock Holmes novel. Holmes, of course, would find some logic in this.

Often he would solve a case only by remembering something he

read in some textbook ten years earlier, but in the end he’d get there, and he’d make it look easy. Looking around, I’m not sure if the evidence is here for anyone to deduce whether the person who did this was left or right handed, or worked as an apprentice shoemaker. Only Holmes would. He was one lucky bastard.

‘Any way we can ID them?’ I ask.

‘We?’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘We’ll start with the woman. She should be simple. Then

work backwards.’

I glance past the examiner towards the tent that shelters the

dead and the wet. The wind chill seems to have dropped by

around five degrees, and picked up an extra twenty-five kilometres an hour. The sides of the tent are billowing out, as though ready to take off. The blanket around me no longer feels warm.

‘So how do … ?’

He raises his hand to stop me. ‘Look, Tate, your colleagues

know what they’re doing. Leave it to them.’

He’s right and wrong. Sure, they know what they’re doing,

but they’re no longer my colleagues. I think about the watch in my pocket, hoping it will have one of those ‘To Doug, love Beryl’

inscriptions on it. Then if s just a matter of finding a gravestone belonging to a Doug who was married to a Beryl. With luck,

that gravestone is here. With luck, these people were given

proper burials by proper priests under the proper conditions,

and not autopsied and dressed up by some homicidal maniac in

his basement.

A four-wheel-drive pulls up next to the tent. Two guys climb

out and walk around to the back of it. They each pull out a scuba tank, then reach further in for more gear.

‘Look, Tate, I’ve told you what I can. It doesn’t involve you, but if you think it does, then take it up with one of your old buddies. I have to get back to work.’

I watch Sheldon as he moves back to the tent. The helicopter

is still buzzing back and forth, the rotor blades sound like the beginnings of a deepening headache. I can imagine what the

journalists are saying, what they’re coming up with, and there is no doubt they’re thriving on it. Bad things happening to good

people make great news.

chapter four

I hate cemeteries. I don’t have a fear of them; it’s not a phobia like someone who is too scared to fly but must fly anyhow. I just don’t like them. I can’t really say they represent all that is wrong with this world, because that wouldn’t be a fair comment. Not logically.

But I feel that way. I think it’s because they represent what happens to all the people in the world who have been wronged, and even then they only speak for the ones who are found. There are others out there in shallow graves, in creeks and crevasses and oceans, or held down by chains, who cannot be spoken for with gravestones, only by the memories their loved ones have of them. Of course, that isn’t a fair statement either. That would be like assuming all of the graves out here belong to victims of crime, and of course only a few do. Most belong to people too old to live, too young to have died, or simply too unlucky to keep living.

My cellphone rings every minute or so as I drive away and

I’m lucky the thing still works after going in the drink. Salt water would have been a different story. As soon as I get past the gates I hit the blockade, where police cars are parked on angles across the road to prevent other people coming to mourn the dead, or

prevent the dead from escaping and mingling with the mourning.

I weave my way through them into the media blockade. It’s the

circle of life out here. Vans and four-wheel-drives with news

channel logos stencilled across the side and aerial dishes mounted on top are parked at haphazard angles, the rain no deterrent for the camera crews and reporters trying to look pretty in the drizzle.

I manage to get past, pretending I can’t hear the same questions yelled at me from every interviewer.

After them comes the first wave of get-home traffic that creates a blockade in the city at this time of the day. My wet jacket and shirt are in the back seat along with the borrowed windbreaker.

I have the blanket draped over my seat so my clothes don’t soak into the upholstery. With the heater blasting on full, moisture forms on the windscreen that the air conditioner can’t keep up with. Every half minute I have to wipe away the condensation

with my palm. I turn on the radio. There’s a Talking Heads song on. It suggests I know where I’m going but I don’t know where

I’ve been. I turn the radio off. Talking Heads have got it wrong in my case.

The first call I answer is from Detective Inspector Landry,

asking me to head into the station to provide a formal statement.

He probably figures he can do the world a favour by keeping me squirrelled away for a few hours running over all the exact reasons that added up to my being in a cemetery with dead bodies that

can’t be accounted for. When I ask him if they’ve tracked down the caretaker, he tells me they’ll inform me when they do, and we both know it’s bullshit.

The next two calls are from reporters. I knew some of them

would recognise me as I was driving away. Reporters are quick

like that. I go further back than yesterday’s news, and these guys have long memories. I hang up on their questions before they can finish asking.

Then my mother calls me, telling me she saw me on TV

sitting in the back of an ambulance and wanting to know what

has happened to me. Clearly the police didn’t have the cemetery as well cordoned off as they thought. I tell my mother that I fell into the lake, that was all, and that I still have all my limbs. She tells me to be careful, that I shouldn’t go swimming with so many clothes, and that she and Dad are worried. Bridget, my wife, she points out, would be worried as well.

When I manage to hang up, the phone rings again and another reporter asks me whether I’m back on the city’s payroll. I decide to switch my phone off, which is a pretty good decision considering the alternative of rolling down my window and throwing it into the elements.

I put both hands on the wheel and start thinking about the

three bodies, wondering if there are more. I start spinning the possibilities around in my mind, but it isn’t long before I have to concentrate less on the corpses and more on trying not to

become one as the traffic becomes thick with SUVs blocking

intersections.

My office is in town, situated in a complex with a hundred other offices, most of them belonging to law and insurance firms, from whom I get most of my business. Following cheating husbands

for divorce settlements and photographing people scamming their insurance providers allows me to pay the rent, and occasionally I even get to eat. Now I’m digging up coffins and swimming with

corpses and the pay is the same. I park in my space behind the building and, still shoeless and saturated, make my way inside to the elevators and ride eight storeys closer to Heaven.

Because most of my clients are in the same building, and any

other business I attract comes through phone calls and word

of mouth, I come and go as I please, allowing my answering

machine to be my secretary. I have enough computer skills to

type up my own reports; I know how to file; and I know how to

make coffee. A maid comes in once a month and drags a vacuum

cleaner and a duster around, but the rest of the time I take care of the spic-and-spanning myself. Private eyes working out of

dumpster officers, armed with fedoras and cigarettes, live only in the minds of scriptwriters these days. My office has nice art, nice plants, nice carpet, nice everything. In fact it’s so nice it’s a struggle to afford it.

I unlock my office door and switch on the light. The air is

warm and has held the smell of this morning’s coffee, probably because half of it got spilled across my desk by accident. The smell kicks my energy level up a few notches. The room itself is not large, and my desk takes up a quarter of it, backing onto a view of Christchurch that sometimes inspires me and sometimes

depresses me. On the opposite side there’s a whiteboard standing up on an easel that I often use to sketch ideas on in an attempt to connect the dots. The carpets and walls are mixtures of fawns and greys that sound like they are named after types of coffee.

There are files stacked on my desk, a computer in the middle, and a bunch of memos I need to take care of.

I glance out at the city. It doesn’t make me feel nostalgic

enough to head back to ground level to see what I’m missing.

I start playing with my cellphone. I turn it back on. It starts ringing. I pop the battery out and sit both pieces under the lamp to dry out.

I move into a small bathroom en-suite and clean up. I have a spare outfit hanging on the back of the door, there for the day I fall into a lake or get shot in the chest. I get changed and ball the wet stuff into a bag.

I take out the watch from my pocket. It’s an expensive Tag Heuer, an analogue, and it’s still working. Batteries in these things normally last around five years, and they’re waterproof to two hundred metres. I look at the back: there is no inscription. But already a time frame is beginning to take place.

My computer is a little slow, and seems to take a minute longer to boot up for each year older it gets. I begin hunting through old news stories online, using search engines to narrow down my browsing, looking for any mention of coffins being reused to make money; but if it’s happened in this country nobody has ever found out.

I run the caretaker’s name through the same search engines and find other people with the same name doing other things in other parts of the world, covering occupations and religions and culture and crime. I find a link that takes me through to a newspaper story about the caretaker’s father. He retired two years ago after forty years of graveyard service.

I use the Christchurch Library online newspaper database to

go through the obituaries, seeing who died last week and who

would fit the description of the woman from the water. I end up with four names, but can’t narrow it down any further because

the obituaries don’t give descriptions or locations for the funerals.

I wonder if Carl Schroder, the detective who told them they

could talk to me, has already figured out an ID, and decide he probably has. Simple when you have the resources. He’s probably circulating a photo of her body to morticians around the city; or, easier still, he’s got the priest from the Catholic church at the cemetery to take a look. If they’ve identified her, then they’ll be in the process of getting a court order to dig up the grave she was taken from. I look at my watch. It’s after five-thirty: everybody will be pushing into overtime but it will get done today.

I put my phone back together and drop it into my pocket. It’s

a ten-minute drive from my office to the hospital, but it takes me thirty in the thick traffic and constant stream of red lights. The hospital is a drab-looking building with no appeasing aesthetics and a design that would equally suit a prison. I park around the back, head to the side ‘Authorised Personnel Only! door, use the intercom and, a moment later, get buzzed inside. I’m starting

to feel pretty cold again, and the idea of seeing the coffin and then having it opened in front of me isn’t warming me back up.

The elevator seems to take for ever to arrive, making me wonder exactly where it’s rising from. When the doors finally open, I ride it down to the basement.

The morgue is full of white tile and cold hard light. It’s like an alien world down here. There are shapes beneath sheets and tools with sharp edges. The air feels colder than the lake. Cabinets are full of bottles and chemicals and silver instruments. Benches and gurneys and trays hold items designed to strip a body down to

the basics.

The coffin looks older beneath the white lights, as if the car ride aged it by a quarter of a century. Plus it’s all busted up. There are cracks along the side, and the top is all dented in. The whole thing has been brushed down before being delivered, but it hasn’t been cleaned. There is dirt and mud caked to the edges of it, and there are also signs of rust. It’s resting on a knee-high table, which puts the lid of the coffin a little below chest height.

I tighten my hands in a failing effort to ward off the cold. My headache has become my sidekick; it beats away with varying

tempos. I wish it would leave. I wish I could leave too. The

smell of chemicals is balancing on a tightrope between being too overpowering and not overpowering enough to hide the smell of

the dead. I can never remember the smell; all I can remember is my reaction; yet for those few minutes, whenever I used to come down here, I thought I’d never be able to forget it. The bodies aren’t rotting, they’re not decaying and stinking up the place, but the smell is still here – the smell of old clothes and fresh bones and old things that can no longer be.

The lid on the coffin is still closed, and it’s easy to imagine there ought to be a chain wrapped around it with one of those

big old-fashioned padlocks attached. I can barely make out my

smeared reflection in places, especially on the brass handles, my face broken up by pit marks made of rust. I run a finger across the shovel marks that the digger and truck drivers pointed out to me earlier. They’re right in the middle of a long concave dent.

‘She’s been opened before,’ the medical examiner says, stepping out of her office and into the morgue behind me, and even though I knew she was there her appearance still startles me. “I wonder what’s inside.’

‘Or what isn’t inside,’ I say.

I put my hand out, expecting hers to be cold when she shakes

it, but it isn’t. ‘Good to see you, Tracey.’

‘What’s it been, Tate? Two years? Three?’

‘Two,’ I answer, letting her hand go, trying to look her over

without appearing to look her over. Though Tracey Walter must

be my age, she looks ten years younger. Her black hair is pulled back and tied into a tight bun; her pale complexion is bone white in the morgue lights; her green eyes stare at me from behind a set of designer glasses. I think about the last time I saw her, and figure she’s doing the same thing.

‘Sure got busted up falling off that truck,’ I say, looking at the long cracks. ‘Caretaker was in a hell of a hurry’

‘You’ve never seen an exhumed coffin before, have you?’

‘Yeah? You can tell that?’

She smiles. ‘Movies don’t show how much weight coffins are

under once they’re in the ground. Often it’s enough to do serious damage. Part of this is from falling off the truck, but most of it will be from the pressure of being in the ground.’

‘So, is there anything you need me to do?’ I ask.

‘Just sign this and you can go,’ she says.

‘You’re not going to open it while I’m here?’

‘It was only your job to be at the cemetery, Tate. It was never meant to extend beyond that.’

“but my job was to make sure Henry Martins made it

here, and those shovel marks on the coffin suggest otherwise.’

She sighs, and I realise she knew all along she would never be putting up much of an argument.

‘Put these on,’ she says, and hands me some gloves and a face

mask. ‘The smell isn’t going to be pretty. But you better not tell anybody you were here for this.’

We shift a little closer to the coffin, and suddenly I don’t want to see what’s inside. This is a topsy-turvy world where corpses bubble up from lakes and coffins are full of empty answers. I pull on the latex gloves and slip the mask over my nose and mouth. If Henry Martins is inside, his fingernails may or may not be blue.

If he isn’t inside and the coffin is empty, then Martins is one of the bodies on the bank of the lake, or deep within its belly.

Tracey sprays some lubricant into the hinges before shifting a small crowbar into place and pushing down.

The coffin lid sticks because of simple physics. They were

designed to take people into the ground, not to bring them back out, and the structure of this coffin has been altered with all that dirt pressing down on it for the last two years. I lean some weight onto the crowbar to help. It starts to groan, then creak; then it pops open. From inside, darkness escapes, along with it the smell of long-dead flesh that reaches through the pores on my mask and right up into my sinuses. I almost gag. Tracey lifts the lid the rest of the way open. I stand next to her and stare inside.

It isn’t at all what either of us is expecting.

chapter five

Christchurch is broken. What didn’t make sense five years ago

makes sense now, not because our perspectives have changed but simply because that’s the way it is. All of us are locked into a belief of how this city should be, but it’s slipping away from us, nobody able to keep a firm grasp as Christchurch slowly spirals into full panic mode. Pick up a newspaper and the headlines are all about the Christchurch Carver, a serial killer who has been terrorising the city for the last few years. The police hate him, the media love him. He’s a one-man moneymaking industry who is stretching

the resources of the police – and the best they can do, it seems, is run ad campaigns on TV in an attempt to enlist new recruits. But the numbers don’t add up. They can’t do, because the police can’t keep up with the Carver, let alone the rising crime pandemic.

There are few solutions – but at least there are some, and

that’s where people like me come into the picture. Some of the smaller jobs get contracted out – the smaller things where a

police presence isn’t required – and in the beginning people

complained. They no longer do.

So yesterday when one of the law firms on the next floor up

contacted me with the job, it seemed like easy money. Crime

fighting has come a long way since Batman and Robin: now

it’s all about the lawyers and, sometimes, even the law. And in this case nobody needed a cop to stand in the cold while a coffin got dug out of the ground. Cops were getting paid to get put

to better uses. They were out there trying to stem the flow of violence, to push back the tides and fight the good fight. So I got paid to be there – a professional making sure the chain of evidence remained intact.

But nobody is paying me to be here in the morgue with a dead

girl in another person’s coffin.

And the police resources are about to get stretched even

further.

I struggle to focus my thoughts. They cover a whole range

of possibilities, as well as emotions. I feel sorrow and pain for whoever this woman is, and can’t see any reason other than a bad one for her to be in this coffin. I’m thinking about hoaxes and jokes, and hoping like crazy this is one of them; and as much as I like to think there could have been an elaborate set-up, I know it is much more than that. This is real. I shouldn’t be looking at a woman, she shouldn’t be dead, shouldn’t be in a coffin that isn’t hers – yet here she is, all laid out in front of me.

Tracey crouches over the coffin. ‘This isn’t Henry Martins,’ she says, not to be funny, not to state the obvious, but matter of factly, in a way that doesn’t suggest the same disbelief I’m feeling, but that the cold part of her mind she must engage to do this job is now fully in control. Tracey’s emotions have been locked away.

‘She’s decomposed, but not badly. Decomp comes down to temperature, soil, depth of the coffin and how long she was exposed to the air before being put in here. No way to tell what age at this stage.’

I’m hardly listening to her. My heart is racing hard as I look down at the body. There are areas where chunks of flesh have shrunken and dried, and other areas where it’s completely disappeared. What she has looks like a shell, so that if I was to poke her with my finger she would turn to dust. The few patches of

skin remaining are almost transparent, doing nothing to hide the

stormcloud-coloured bones that for the most part are exposed.

Her face and eyes have gone, just dregs of dried-up skin and flesh and scalp hanging onto her skull. Her teeth look too large with nothing to hide them. Her hair is swept out fanlike beneath her body; it is long and dark brown and I imagine it was once well kept, that she liked to run her fingers through it, that it smelled of shampoos and conditioners, and it would brush against her

lover’s face as they held each other as one day became another.

Her fingers are only bone; one rests across her chest, the other by her side. Resting between her palm and her thigh is a small diamond ring that in the light of the morgue refuses to sparkle. I figure it came loose when her fingers rotted away, and got shaken free when she fell off the back of the stolen truck.

Her clothes don’t seem to line up right; her short dress is

twisted and the buttons on her blouse are out of line, as if she dressed in a hurry or somebody else dressed her after she was

dead. I dig my hand into my pocket and start playing with my

car keys, wrapping them into my handkerchief over and over as

my mind races.

Tracey looks up at me. ‘Jesus, are you okay? You look like

you’ve seen a ghost.’

I can feel sweat starting to slide down the side of my body. It has to be near freezing in here and I’m sweating.

‘There were other people in the water, Tracey,’ I say, and the words are hard to form. ‘Maybe that means other girls, and if

there are … Jesus, I fucked up.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Two years ago. I should have dug Henry Martins up two

years ago and we would have found this girl then. We would

have known we were looking for a killer. We might have got him before he killed others.’

Tracey looks at me but doesn’t know what to say. She can’t

tell me the world doesn’t work that way, because we both know

that it does. She doesn’t say anybody could have made that

same mistake. She doesn’t try to tell me it isn’t my fault. All that happens is that her shoulders sag a little and she looks

away, unable to maintain eye contact with me.

‘Shit,’ she whispers, still looking at the floor. ‘You need to leave now, Theo.’

‘Come on, Tracey, there’s got —’

‘I’m serious,’ she says, looking up. ‘You wanted to know if

Martins was inside – well, now you know. That was the deal.

You can’t look at this woman and think it’s become your case. All you can do by being here now is compromise the investigation.’

‘You don’t get it, do you?’

‘What? That you could have made a difference two years

ago? I know the case, and you’re right. It could well be that you messed up and other girls have paid for it, but how many are still out there because you have taken bad people off the streets?’

‘This isn’t about checks and balances.’

‘I know that. Do you? And I know that you have to leave.’

‘You think that’s what she’d want?’ I ask, nodding towards

the dead girl. ‘Or do you think she’d want as many people as she could get trying to find who did this to her?’

‘Come on, Theo, it’s time to go. I’ll let you know if one of the bodies that turns up is Martins’.’

‘Yeah. Okay, do that,’ I say as she walks me to the corridor.

The moment we step into it, her cellphone rings. She shakes

it open and starts talking. I pat down my pockets, then turn

them inside out. I mouth the word ‘keys’ to her and point back towards the morgue.

‘Make it quick,’ she says, lowering the phone so the person on the other end can’t hear.

I walk back into the morgue. I stare at the dead girl and I

wonder what she looked like before Death crammed her into

this coffin, taking everything away from her in one brutal insult.

Looking at this cheap imitation of her makes me feel ill.

Tracey is finishing up her phone call when I rejoin her in the corridor.

“They’ve found the one that sank again, and another one,’ she

says, slipping the phone into her jacket. ‘That’s four in total.’

‘Any IDs?’

“They’re close to ID-ing one of them.’

–How’d she come up to the surface? The freshest one?’

‘It was the cinderblock,’ she says. looks like the rope was

tied around it, but those cinderblocks can have sharp edges. The block landed against another block down there, and it damaged

the rope. It cut through it partly. Gas build-up in the body was enough to break it. Look, you really have to leave.’

‘I get the feeling I’m going to be hearing that a lot over the next few days.’

“Then do yourself a favour and drop this thing, she says,

before turning away and heading back into the morgue.