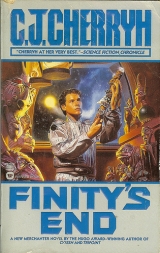

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Lie. They all lied.

The inner door opened, and he walked out of bright light into a dimmer tiled corridor. No one was there. The corridor went back, not far, before four lighted corridors intersected it, and then it quit. A ship’s ring was locked stable while they were at dock, and the four side corridors all curved up . The up would be down when the ship broke dock and the ring started to rotate, but until it did, this seemed all there was, a utilitarian hallway, showing mostly metal, insulated floor, the kind of insulated plating you used if you thought a decompression could happen.

A door to the right was open. He walked that far, his boots making a lot of metal racket, but a woman came out and met him. So did another woman, and a man.

“Fletcher, is it?” the woman said, and put out a hand.

So, hell, what did he do? He purposely misunderstood and handed her the passport

“Welcome aboard,” she said without a flicker, and pocketed it without looking at it. “Not much time. I’m Frieda N. This is Mary B. And Wes. There’s only one. There’s no other Fletcher, either. You’re just Fletcher.”

He’d never been anything else. Frieda N. held out her hand a second time, and he took it, finding himself lost in the information flow, wondering if she was related, how she was related and how any of these people were related to his mother. His mother had talked about her mother. He had a grandmother. He didn’t know whether she was still alive or not, but spacers lived long lives, and stationers aged faster. He supposed she might be here.

For the first time it came to him… there was something personal about these people who assumed they owned him. These people who’d owned his mother. And left her.

Others came into the hall. “This is your cousin June, Com 3. And Jake. Jake’s chief bioneer, lower deck Ops.”

June was an older woman, with a dry, firm handshake, and communications didn’t seem to add up to anybody he needed to deal with. Jake had a thin face, a sober face, and looked like a cop he knew: not unnecessarily an unpleasant man, but somebody who didn’t have much sense of humor.

Then another man came in, in the kind of waistlength, ribbed-cuff jacket spacers wore over their coveralls where they were working near the cold side of the docks. Silver-haired. A lot of stripes on the sleeve.

“Fletcher,” Jake said, “this is Madison, second captain.”

He’d already spotted authority, and took the hand when it was offered him, feeling overwhelmed, wobbly in the knees, wobbly in his mental state, knowing he was going to want to settle how to deal with these people, but all his scenarios of defiance had evaporated, in Quen’s little advisement, her outright bribe for good behavior.

Not smart at least to screw things up from the start. Start friendly, start sane, try , one more stupid time, to make the good impression with one more damned family—his own family.

“Welcome aboard.”

“Yes, sir,” he said, and Finity ’s second captain held onto his hand, a cold-chilled, dry clasp. He felt trapped for good and certain. I don’t know you people, he wanted to shout. I don’t give a damn. And here he was doing the safe, the sensible thing, as somebody else arrived to take his hand. It was a cousin named Pete, a cargo officer, nobody, in his book. It was one more introduction, and he wanted just to escape to somewhere private and shut the door.

“Welcome in, Fletcher.” Pete was a dark-haired man with a trace of gray in a beard unusual on dockside—you only saw them on spacers; and it was worth a stare; he was aware he was staring, losing his focus, while strangers’ hands patted his shoulders, welcomed him in a chaos of names and emotions.

“Pete,” Jake said, “you want to show Fletcher to the safe room?”

“Yeah, sure,” Pete said, and indicated the duffle. “That’s all the baggage you brought? I’ll stow it for you.”

“Nossir,” he said, and held onto it. Desperately. “No.”

Pete relented. Jake said, “Get Warren to make him up a patch set soon as we leave dock.—What’s your height, son? Height and weight, Pell Standard. Six feet?”

“About. Eighty-five kilos.”

“Baggage weight?”

He knew what he’d come downworld with. What they let you bring. “Twenty-two.”

“Got it.” And with no more fuss and no more word about the duffle Pete took him out to the corridor and to another room at the next cross-corridor, no simple room, but a vast curved chamber, a VR theater, he thought, with railings where everybody stood. Old people, younger ones. A theater full of relatives, hundreds of them, all staring in sudden quiet in their conversations. “This is Fletcher,” Pete called out, and someone cheered. “He’s late, but he’s here!” Pete said. Others called out hellos and welcome aboard, and, grotesquely enough, applauded.

“Ten minutes,” Jake called out, and Pete showed him to a place to stand in the third row, where people leaned and reached out hands to shake, or patted his back or his shoulders, throwing names at him. At distances out of reach, they all talked about him: there couldn’t be another topic in the room. Of the ones in earshot, who called out names to him or introduced each other, there was a Tom R., a Tom T., a Margaret, a Willy and a Will, there was Roger Y., Roger B., and a single Ned; there was a Niles senior, a man with silver at the temples, and Jake’s brother was Louis down in cargo, not to cross him with Lou on the bridge, who was Scan 2, third shift.

Bridge ranks. Post designations. Old people. Senior crew, with hairline wrinkles that spoke of rejuv.

Then a handful of crew trooped in with their quilted jackets literally frosted with cold, ice cracking as they moved. There was a Wendy who looked barely in her twenties, and a William and a Charles who wasn’t Charlie because Charlie was his uncle, chief medtech, who was at his station, and his mother was Angie. There were half a dozen Roberts, Rob, Bob, Bobby, and Robbie and a kid they just called JR, not to cross him with his uncle Captain James Robert, senior captain, who besides being famous all over the Alliance always went by both names.

Pretentious ass, Fletcher said to himself.

Jim, James and Jamie were all techs of various kinds, old enough to have a touch of gray; and there was McKenzie, Mac, Madden, and Madison that he’d already met.

He got the picture, if not most of the names. You carried Names, and there wasn’t much creativity about it inside a line of relations: the ones that carried the same Names tended to be close cousins, the way they were introduced

Close cousins as opposed to remote cousins, which everybody was to each other.

Hi , he said uneasily to each out of reach introduction, saved by distance from shaking hands, resenting the welcome, resenting them with all the integrity he could muster. He’d had about half a mother, that was the way he thought about it: he’d had about half her attention half the time, but that was all the real relative he ever acknowledged. And here were a ship full of people all claiming he was tied to them in some miraculous way that didn’t mean a damn to him.

Friendly, he supposed so. People had been friendly before, in schools where it was welcome in until they got to know him up close and discovered he wasn’t up to their standards in some way or another. Not part of the right clubs. Not part of the right experiences. The right family. The right mother. The right attitude.

He’d fought his sullen tendencies for years just to get into the program, no reform, no real change in him. Just in his objectives. God , he’d been friendly. He’d watched how the accepted ones did it and he’d learned the lessons and copied– forged —good behavior. And here he was doing it all over again, new start, one damned more time, one damned more try. Stunned, shocked, still marginally battling the tranquilizer they’d given him, he did it by now on autopilot, acting the shy, reserved, pleasant fool with every one of them while his brain, behind a chemical shield the shuttle authorities had given him, was passing from numbed shock to outright anger.

Hate you , he kept thinking while he smiled and shook hands. But that wouldn’t get him home again. Wouldn’t ever get him to Downbelow.

The monsoons were starting. The shuttle had almost delayed launch because of the weather and teased him with a last, aching hope that it couldn’t get off the ground and he’d miss his ship even yet

Hadn’t worked, had it?

The monsoons were starting and Melody and Patch were off, by now. He’d not seen them again.

He ran out of hands to shake, and people close enough to shout introductions at him. “One minute,” someone said, and he knew then that this was it: it was countdown. Pete showed him a toe-hold, a long slot in the carpet, and encouraged him to settle his toes there. He did, and gripped the safety rail, watching the tendons on his own hands stand out as white as the knuckles.

Then someone started singing, for God’s sake, one of those rowdy old spacer songs, and the whole company started in, more men than women, deep voices. Cousin, uncle, whatever-he-was Pete elbowed him in the ribs and grinned at him, wanting him to pick up on the words and join in. It was a spooky sound: he’d never heard singers who weren’t hyped with sound systems, but this went through the air and off the walls, and it was a lot of men’s voices, singing about space, singing about going there—when he didn’t in the least want to.

That segued to another song that rocked and rollicked, that caught up his basic fear of space and began with its music and moving beat to break into parts of his soul he didn’t want broken into right now, painful parts, aching with loss at a parting he didn’t want.

Came a powerful thump and clank, and a light started flashing in the overhead. But that singing drowned other sounds as they started to move, and bodies swayed. For a moment there wasn’t any up or down, and he grabbed the rail hard. Pete, next to him, grabbed him and held on, a human reassurance—nobody even missing a beat except to laugh, and he had his toe hooked in the slot, but he wasn’t sure it was enough.

Terror whited out all other thoughts, then, terror that things were moving so fast, that it was all real, and all his objections were spent to no avail. They’d just broken their connection to Pell. They were backing away.

The floor began just slightly to be the floor again, but he was afraid to let go, not clearly reasoning what had just happened, because Pete didn’t let go of his arm and something more might be coming. People were laughing, and the song was rowdy and wild, while something in his heart went numb and the outer body was shaking. He was afraid Pete knew how scared he was, and that they’d all make some joke of it. But down, down, down his body settled, force pressing his feet to the floor, while a terrified fraction of his mind told him the passenger ring was rotating now, and the ship was still drifting back from the station dock, inertial.

Came a stress then that made him lose his sense of up and down. Bodies, tightly packed all around, swayed at the rails. People cheered, excited, glad to be going.

The singing had stopped, with that. He kept a white-knuckled grip on the rail, not knowing how long it would go on. Then it did stop, and there was thundering quiet, as if he’d gone deaf.

“Good lad,” Pete said. “We’re away. Duty stations. Stay by the door and somebody’ll post you somewhere. Mind, if there’s a take-hold, hang on to the rails.”

He unbelted amid snicks and snaps from all over the hall. He got shakily to his feet as Pete hurried off, as people began moving for the door, everyone exiting into the corridor with a buzz of talk and a feeling that everybody except him knew where they were going and had to be there. Urgently.

He was scared of what they called take-holds, motion alarms. He’d seen enough disasters in vids to make him nervous. He lost Pete in the rush and set himself beside the door where Pete had told him to be, standing with his duffle beside him as people moved hurriedly by him. He could see up the curved floor that was walkable now and lighted in either direction, curves sharper than the vast curves of Pell Station. If the scale was shorter, their rotation rate had to be higher, and he felt sick at his stomach.

Cold. Chilled through. Everything was browned metal. Noisy. All around him, hurrying bodies, sharp shouts of orders or information he didn’t begin to grasp.

“Fletcher!”

He jerked about at the sharp address. The kid named JR came up to him. The captain’s nephew. Fa-mi-ly. Highest of the high on this ship.

“Stow that fast,” JR said pointing at the baggage. “For future information, you’re not to carry baggage aboard. You turn it in at the cargo port. You get around to your quarters first thing, get your stuff put away, don’t leave any latches open—

“I’m not stupid,” he said.

“I didn’t ask if you were stupid. I said latch the lockers tight.”

“Look here…”

“I’m an officer,” JR said. “Junior captain. You’re excused for not knowing that. Clean slate, fast orientation, pay attention. This is A deck. Up above is B. Stay off B deck. Everything you want’s on A until you’ve got orders to be on B. Your quarters number is A26. You copy?”

“Yes.”

“That’s yes, sir, Fletcher, if you’ll kindly remember.”

“Yessir,” he muttered, too tired to fight. This JR didn’t look a day older than he was. But he was the captain’s nephew. He got the picture.

“Get your stuff tucked in, get down to A14—that’s the laundry, same corridor, down ten doors—and get some work clothes before we hit the safety perim and do another burn. You’ve got time. That’s about an hour. You draw three sets of coveralls, underwear, what you need; and when we’re underway that’s where you’ll report for duty. A14.”

“Laundry?”

“Laundry and commissary. You start out there, work your way up to galley. We’ll see later what you do know.”

“Biochem. Life sciences.” He didn’t want a job. But he had most of his degree. He’d worked for it. And he didn’t do laundry .

“You’ll get a chance at whatever you’re qualified to do,” JR said, tight-lipped and tight-assed, about his size, maybe ten kilos less. And self-important as hell. “While I’m at it, let me explain something to you as politely as I can. This whole ship delayed five days for you. It never will again. If you’re on a liberty and you don’t answer board call, you’re on your own. We won’t buy you back twice. You know what two hundred twenty-four hours at dock costs this ship?”

“Damn you all, you can leave me at this station and I’ll be happy. Give me a suit. I’ll take my chances station’ll rake me in. That’s the only favor you could do me!”

JR gave him a look as if maybe he hadn’t quite understood that part of the equation. “Then you’re out of luck,” JR said then. “If it were up to me, you’d be on the dockside. But you’re here. You’re in my crew, and what I ask of you is simple: show up on time, do your job, wait your turn and ask if you don’t understand something. This ship’s on a schedule, it moves, and physics doesn’t care what your excuse is. If you hear a siren, you see these handholds?” JR gripped a handle inset in the wall. “You grab one and hang on. That’d be an emergency. It happens. If you don’t hold on, you could die. Fourteen did, last year. End warning. Go pick up your clothes at the laundry window. That’s A14, down to your right.”

He picked up the duffle and started off.

“Yessir,” he muttered, “yessir. Yessir.” And walked off.

He had something material to lose if he got on the wrong side of this officer who looked his age and acted as if he owned the ship. He learned fast. He took the cues. He knew now the guy was a tight-assed jerk. He knew sooner or later they’d come to discuss it again.

He went where he was told, feeling sick at his stomach and telling himself Quen was probably conning him and had no intention of putting him back on station. He wasn’t important enough to matter to people on her level. He never had been.

The Neiharts were far more important to Quen, collectively. For their sake, that jumped-up jerk nephew of the captain would be. And if by then they had an active grudge, JR would use every influence to see him set down. He knew that equation, in his heart of hearts.

Lies. Lies that moved him here, moved him there. When the world stopped shifting on him for an hour, he’d think, and when he learned the new rules well enough to know how to maneuver in this new family, he’d do something. Not yet. Not now.

Not soon enough to prevent being shipped out of the solar system. He had no hope now except to live that year, and get back, and see if the court or Quen had another round to play.

That wasn’t, JR said to himself, watching the retreating view, the most auspicious beginning of a situation he’d ever set up… and truth was, he hadn’t handled it as well as he could.

That was a seventeen-year-old, not someone in his mid-twenties. You forgot that when you looked at him. It was too easy to react as if he were far older.

The Old Man had told him, when they knew the shuttle was on its way, “He’s all yours.” And then added: “All these years. All these years, Jamie. The only one of all the lost kids we’ll ever get back.”

Five days. Five days they’d held in port, with cargo in their hold, the heated cans drawing power, the systems up, because until the third day, they hadn’t gotten a medical go-ahead on Fletcher’s shuttle ride up, and they hadn’t been sure they could get a shuttle flight out through worsening atmospheric conditions. Then it had been more expensive to bring systems down again and go back on station power than it was to stay on their own pre-launch ready systems. That meant that crew had had to board to run those systems, cycling in and out of a departure-ready ship to the annoyance of customs and the aggravation of crew stuck with the jobs and having to suit and clamber about in the holds.

Fletcher was welcome aboard and politely, even warmly, welcomed aboard, but it was with a certain edge of irritation with their fast-footed cousin, from all of them who’d been put on that unprecedented hold.

Fletcher had also broken ten thousand regulations down on the planet and fled into the outback of Downbelow, just in case holding up a starship wasn’t enough.

He’d been picked up at death’s door and lodged in a Downbelow infirmary while the planetary types and batteries of scientists tried to figure out what he’d done, what he’d screwed with, what he’d screwed up and what damage he might have done to the only alien intelligence in human reach.

A Finity crew member had done that. That was how the outside would remember it, and Fletcher, an honorable name, would be notorious in rumor forever if he had in fact lastingly harmed anything on the planet.

Quen had shoved Fletcher toward the ship at high speed, keeping him out of station custody by taking him directly across the docks, not ever bringing him into administrative levels and procedures where Pell administration could get their experts near him for another round of questioning. Fast work from a canny administrator.

And, thank God, Finity had been able to make departure on the schedule they’d finally been able to set, while all Pell Station had to be buzzing with speculation regarding the delay that kept Finity in port—speculation that was no longer speculation as the news filtered through the station legal department and the rumor mill that Finity was recovering a long-lost crew member. Then the story had been all over station news.

Notorious in Finity ’s affairs from the day he was born, an embarrassment and a tragedy on Finity ’s record from the hour his mother had begun her downward drug-induced slide—Fletcher was all theirs now. Captain James Robert set great store by recovering him, and he was somehow supposed to make something of him.

Meanwhile the report up from the medics on the planet said Fletcher’s lungs were clear.

So his guess was right and despite the speculation to the contrary, Fletcher hadn’t half tried to kill himself rather than be taken to the ship. Fletcher could have walked out of the domes with no cylinders if he’d wanted to do that, as best he understood the conditions down there.

No. It had been no suicide attempt, regardless of the speculation in the station news. Fletcher simply had tried to lie low until schedule forced them to abandon him again, and hell if the Old Man was likely to give him up on that basis. It had come down to a test of patience, an incident now with an unwanted publicity that could harm Quen at the very least

He found it significant that the Old Man hadn’t even asked to see the nephew on whom they’d spent such effort. It was a fair guess it was because the Old Man’s temper was still not back from hyperbolic orbit.

That meant, in the Old Man’s official silence toward young Fletcher, the whole business of settling Fletcher in was definitively his problem.

His problem, his unit, his command, and his job to fix.

“So what do you think?” Bucklin stopped beside him to ask as he stood thinking on the Fletcher problem.

Bucklin had a temper where it came to junior misbehaviors; and he already knew Bucklin was annoyed. But Bucklin was also the one who’d stand by him, next-in-command, as Madison had stood by the Old Man in the last century of time, come hell or high water. They were right hand and left, both in the captain’s track, both destined for backup to Alan and Francie when they succeeded Madison and the Old Man. They’d always been a set—and became closer still over years that had seen their mothers lost, when half the juniors alive had died in the blow-out, when they’d had no juniors born for all of Fletcher’s seventeen years.

The last kid. The very last until one of the women got Finity another youngest, and until stationside encounters began to fill the long-darkened kids’ loft: that also was part of the change in the Rules. Real liberties. Unguarded encounters. Finity ’s women were going off precautions, and some talked excitedly, even teary-eyed, about babies—the scariest and most irrevocable change in the Rules, the one that, at moments, argued that the Rules change was permanent.

But the need for children born was also absolute. The ship had to, at whatever risk, repopulate itself.

What do you think ? Bucklin asked. What he thought was tangled with yesterday and bitter losses.

“Just figuring,” JR said. “Ignore the face. The guy’s seventeen. Just keep telling yourself those are station-years. The Old Man said it. Out of all those years, he’s all the replacement we’ve got. So here we are.”

Chapter 7

Number A26. At least they believed in posting numbers inside the ship. Fletcher found the door of his quarters and elbowed the latch. It wasn’t locked. And it slid open on a closet of a room with two bunks, barely enough room between them for a person to stand up. A couple of lockers at the end. God, it was a closet . And two bunks? He had to share this hole? With one of them ?

He wasn’t happy. But it was a place, and until now he’d had none. He walked in and the door shut the moment he cleared it. He stood there, appalled and this time, yes, he tested it out, angry . He wanted to throw things. But there wasn’t a single item available except the duffle he’d brought, no character to the place, just—nothing. Cream and green walls, lockers that filled every wall-space above the mattresses and bed frames. Cream-colored blankets secured with safety belts. That promised security, didn’t it?

A check of the lighted panel at the end of the room, which looked to fold back, showed a toilet and a shower compartment, a mirror, a sink, a small cabinet. The place was depressingly claustrophobic. He checked the lockers out, found the first right-hand one full of somebody’s stuff—bad news, that was—and slammed it shut, tried the left-hand side and found it empty, presumably for the clothes he’d brought.

There was more storage under the bunk, latched drawers that pulled out. He unpacked his duffle and stowed his dock-side clothes, his underwear, his personal stuff, where he figured he had license to put them.

Most carefully, he unwrapped what he really wanted to put away safely, the most precious thing—the hisa stick he’d wrapped in layers of his clothes.

The stick that customs hadn’t found. That the authorities on Downbelow hadn’t confiscated. That everything so far had conspired to let him keep. It was hisa work. It was a hisa gift.

It was illegal to touch, let alone to have and to take off-planet. But hisa bestowed them on special occasions—deaths, births, arrivals. And partings.

He smoothed the cords that tied the dangling feathers. The wood—real wood—was valuable in itself. But far more so was the carving, the cord bindings, the native feathers—only a very, very few such items ever left Downbelow, and the government watched over those with jealous protection from exploitation of the species, their skills, their beliefs.

But this particular one was his. He’d told his rescuers how he’d gotten it, and where he’d gotten it, and wouldn’t turn it loose. The planetary studies researchers had grilled him for hours on it, and he’d thought they might try to take it—but they’d only asked to photograph it, and put it through decon, and gave it back after that, and let him take it with him. He’d expected customs would confiscate it and maybe arrest him for trying to smuggle it out, a hope he actually entertained, thinking that maybe a snafu like that would get him snagged in the gears of justice again and maybe keep him off the ship—but Quen’s intervention had meant he hadn’t even had to deal with customs.

So one obstacle after another had fallen down, maybe Quen’s doing all along, and by now he supposed it really was his. And it was all he’d managed to take away that meant anything to him.

It meant all the hard things. It meant lessons Melody had tried to teach him—and failed.

It meant parting from where he’d been. It meant a journey. It meant eyes watching the clouded heavens. It meant faith, and faithfulness.

Maybe a human who was born to space couldn’t have the faith hisa had in Great Sun. Maybe he couldn’t believe that Great Sun was anything but what they said in his education, a nuclear furnace. Maybe Great Sun wasn’t a god, maybe there was no god, or whatever hisa thought or expected when they looked to the sky. But Melody was so sure that Great Sun would take care of his children, that Great Sun would always come back, that the dark never lasted…

The dark never lasted.

For him it would. Forces he couldn’t control had shoved him out where the dark went on forever, where even Melody’s Great Sun couldn’t walk far enough or shine brightly enough. That was where he was now.

But this stick he touched had lived, once. These feathers had flown in the fierce winds, once. Old River had smoothed these stones. All these things, Great Sun had made. And they were real in his hand, and he could remember, when he felt them, what the cloud-wrapped world felt like. They were his parting-gift.

Hisa put such sticks on the graves of the dead, human and hisa. They put them near the Watcher-statues. And when the researchers asked, bluntly, why, the hisa didn’t have the words to say.

But he knew. He knew. It was when you went away. It reminded you. It was a memory. It was the River and Great Sun, it was weather and wind. It was all those things that he’d almost touched, that the clean-suit only let him imagine touching without a barrier. It was waking up to a sunrise, and watching the world wake up. It was sleeping in the dark with no electric lights and waiting for Great Sun to find his child again– knowing that Great Sun would come for him the way Melody had come in the darkest hour of his childhood, when he was hiding from all the crazed authorities.

That was the faith the hisa had. That was what he took away with him.

Bianca had sworn she’d wait for him. But he knew. People didn’t keep such promises. Ever. And hisa couldn’t. Their lives were too short, too precious for waiting. It was why they made the Watchers.

And now Quen had tried to psych him with this last-minute offer of hers… just a psych-out. A ploy to get Fletcher to behave, one more time.

He wound the dangling cords about the stick and put it away in the back of the underbunk drawer, behind his spare station clothes, so no prying roommate would find it.

He quietly closed the drawer, telling himself he was stupid even to think of falling for Quen’s line. He knew the drill. He could almost manage a cynical amusement past the usual little lump in his throat that conjured all the other bad times of his life. Have a fruit ice, kid. Have another. You’ll like it here. Look, we’ve got you a teddy bear.

Ten weeks later the new family’d be back to the psychs saying he was incorrigible.

This one was already a disaster.

Work in the laundry, for God’s sake. He’d pulled himself from police-record nothing into a degree program in Planetary Studies, and his shiny new family had him doing laundry and matching socks. That was damn near funny, too, so funny it made the lump in his throat hurt like hell.

He latched the drawer. The locker didn’t have a lock. The bath didn’t have a lock. When he looked at the door to the outside, it didn’t have a lock. There wasn’t anywhere that was his.

All right, he said to himself for the tenth time in five minutes, all right, calm down. A year. A year and he’d be back to Pell and he’d survive it and if Quen reneged, he’d go to court. Do what they said, keep them happy until, back at Pell after that year, he ran for it and held Quen to her word.

Meanwhile the captain’s nephew had said go back down to the laundry and check out some clothes. He could do that, while his heart hammered from anger and his ears picked up a maddening hum somewhere just below his hearing and he wasn’t sure of the floor. He told himself he was going to walk around, telling himself he wasn’t going to be sick at his stomach, he wasn’t even going to think about the fact that the ship was moving. He walked out to the hall and down to A14, to the laundry.