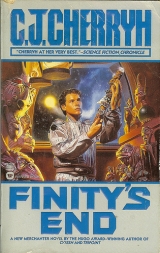

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 33 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

He had so, so much to tell her when they met.

If they ever met.

He’d have to mail her the pin. He couldn’t go back to the Program. He’d fractured all the rules. He’d lost that for himself, in the perverse way he had of destroying situations he knew he was about to be ripped out of and taken away from. Especially if you almost loved them, you broke them, so you didn’t have them to regret. Sometimes you broke them just in case.

That was what he’d always done. He could see that now, too… how he always managed the fight, always provoked the blowup, so he could say he’d left them , and not the other way around. He had that definitely in common with Jeremy: the quick flare of anger, the intense passion of total involvement—followed by angry denial, total rejection. Go ahead. Move out. Don’t speak to me.

Silly Fetcher. He could hear Melody saying it, when he’d been too kid-like stupid even for her downer patience.

Silly Jeremy, he wished he knew how to say. Silly Jeremy. Be happy. Cheer up.

Change, to a prosperous station, was a frightening prospect.

Change and new information meant that those here who thought they knew how the universe was stacked might not know what was in their own future.

Change in the Alliance and Union relationship might abrogate agreements on which Esperance seemed secure. They stalled. They argued about minutiae. There was a long stall regarding an alleged irregularity in the customs papers. That evaporated. Then they discussed the order of the official agenda for an hour.

Madison was ready to blow. The Old Man smiled benignly, seated at the table, while the Esperance stationmaster absented himself to consult with aides.

And came back after a half hour absence, and finally took his seat

“The legal problems,” the stationmaster said then.

“Third on the agenda,” Alan said.

“We cannot talk and discuss matters pertinent to a pending suit…”

“Third,” Alan said.

“We’re vastly disturbed,” the Esperance stationmaster insisted, “by what seems high-handed procedure regarding a ship against which no charges have been made, sir. I want the answer to one question. One question, sir.”

“Not one question,” Madison said. “As agreed in the agenda.”

“We can not agree to this order. We can’t talk beyond a pending suit. We wish to move for a meeting after the court has ruled.”

“You can have that, with Finity ’s trade officer. In the meantime … you’re not meeting with Finity ’s trade officer.”

Madison, at his inflammatory best. JR tucked his chin down and listened to the shots fly.

“I cannot accept Alliance credentials from a ship in violation of Alliance guarantees.”

“This is Alliance business, which you may not challenge, sir.”

“I ask one question. One question. On what authority do you pursue a ship into inhabited space?”

“What ship?” James Robert asked, interrupting his idle sketching on the conference notepad—looking for that moment as if he had no clue at all, as if he’d been in total lapse for the last few minutes, and JR’s heart plummeted. Is he ill ? the thought came to him.

Outrage mustered itself instantly on the other side. Outrage perfectly staged. “ Champlain , captain.”

James Robert looked at Madison on one side, and at Francie, Alan, and him, on the other. Blinked. “Wasn’t that ship docked when we entered system?”

“Final approach to dock, sir,” JR said, and all of a sudden knew the Old Man had been far from oblivious. “As we came into system. Days ahead of us.”

“And what was its last port?”

“Mariner.”

“While our last port was Voyager.” It was dead-on focus the Old Man turned on the Esperance officials. “Hardly hot pursuit. They’d passed Voyager-Esperance before we got to that point. Our black-box feed will have the latest Voyager data. Theirs won’t. Ours will have an official caution from Mariner on their behavior. Theirs won’t reflect that. They undocked before we or Boreale left Mariner. Seems a case of flight where no man pursueth, stationmaster. Boreale might have had a dispute with them we know nothing of. We didn’t chase them in. And I invite anyone with doubts to examine the black-box record Esperance now has from the instant we docked. It will show exactly the facts as I’ve given them, including a stop at Voyager.”

Bravo, JR thought, and watched the expressions of station officials deeply divided, he began to perceive, between pro-Union and pro-Alliance sentiments… and those who simply wanted to go on playing both ends against the middle. And unless he missed his guess the stationmaster hadn’t accessed their records yet to know where they’d been. Careless, in a man leveling charges.

Careless and impromptu.

“But a military ship can access a black box on its technical level,” the stationmaster said. “And your turnaround at Voyager must have set a record, Captain Neihart, if you stopped there.”

That man was their problem. William Oser-Hayes. There was the chief source of the venom. JR wanted to rise from the table and wipe the look from the man’s face.

The Old Man did no such thing. “Necessarily,” the Old Man said calmly “The military does have read-access. And can delete information. But black boxes… and you may check this with your technical experts, do show the effects of military access. Ours wasn’t accessed. Check it with your technical experts.”

“Experts provided by Pell.”

Oh, the political mire was getting deeper and deeper. Now it was all a plot from Pell. And the Old Man was playing cards from a hand they had far rather have reserved for court, for the lawsuit. It gave their legal opposition a forecast of the defense they had against the charges, even if it was a very good defense—an unbreakable defense in a port where the judiciary was honest.

The way in which certain members of the conference looked happier when the Old Man seemed to win a point indicated they were not facing a monolithic administration and that there was sentiment on Finity ’s side. But the fact that Oser-Hayes did all the talking and that all the ones who looked happy when Oser-Hayes seemed to score sat higher up the table indicated to him that they had a serious problem—one that might well infect the judiciary on this station. That the attack from the opposition had come from the Esperance judiciary and not from, say, the Board of Trade or the other regulatory agencies clearly indicated that the judiciary was their enemies’ best shot, the branch most malleable to their hands.

Not a fair court, JR said to himself. The legal deck was stacked, and they might lose the suit even if the other side was a no-show and the evidence was overwhelming. That they’d bullied their way into this meeting indicated Oser-Hayes wasn’t absolute in his power, that he regarded some appearances, and had to use some window-dressing with some of his power base to avoid them bolting his camp.

He was learning, hand over fist, that precisely at the moments one wanted to rise out of one’s seat and choke the life out of the opposition, one had to focus down tightly and calmly and select arguments the same careful way a surgeon selected instruments. Oser-Hayes was no fool: he meant to provoke the choke-him reaction, which might get the Old Man to make a tactical error—if the Old Man weren’t one of the canniest negotiators alive. One time Oser-Hayes had thought he was dealing with a drowsing elder statesman a little out of the current of things: one time the Old Man had let him stumble into it, and start the meeting. They were into the agenda, after balking for hours. A parliamentary turn would see them handle it, and revert back to the top of the list before Oser-Hayes could think how to avert it.

They were talking. They had accomplished that much.

But this talk of technical experts provided by Pell as a source of suspicion… this talk of deliberate sabotage by agents from the capital of the Alliance—as if the Alliance government and Alliance-certified technicians would likelier be the source of misinformation and duplicity, not some scruffy freighter running cargo in the shadow market and most probably spying for Mazian—that was a complete reversal of logic. The black boxes on which the network that ran the Alliance depended were of course suspect in Oser-Hayes’ followers’ minds; the word of Champlain against them was of course enough to stall negotiations and tangle them up in the issue of universal conspiracy, which Oser-Hayes insisted on discussing.

Whatever the Old Man’s blood pressure was doing at the moment, there was no sign of it on his face. And the Old Man came back with perfect calm.

“Would you prefer those experts provided by Union, sir? I don’t think we can access them. But Boreale can certainly attest every move we’ve made. And the next ship arriving in this port from the Mariner vector will most assuredly reflect exactly the same information, as surely the stationmaster of Esperance knows as well as any ship’s captain—unless, of course, our technical experts have gotten in and altered the main computers on Mariner, then accomplished the same with seamless perfection on Voyager in ways that would withstand cross-comparison for all future ship-calls at any station in the Alliance—”

“Sufficient time to have gotten signatures on documents is all you need.”

“Ah. Is that your fear?”

“Apprehension.”

“Apprehension. Well, in respect of your prudent apprehensions, we have the precise case number that will pull up previous complaints on Champlain , including those that will have different origins and dates than any ship-call we’ve made. To save your technicians, I’m sure, weeks of painstaking effort…”

Weeks only if the technicians meant to stall.

“That is something our military status can do somewhat more efficiently: access case numbers. In this case, the last stamp of access on the complaint itself will be the court at Mariner.”

Hours of meeting and they hadn’t even gotten to the agenda. In that sense, William Oser-Hayes was making all the political capital he could, and JR wagered with himself that behind the scenes Oser-Hayes had people working the records, excavating things with which they could be ambushed, burying them at least beyond access within this port, although the very next ship to call at the station would dump a load of information which would restore the missing files.

The Old Man hadn’t mentioned the fact, but a military ship had the means to take a fast access of a station’s black-box system. JR remembered that suddenly in the light of the local resistance. Finity under his command had taken such a snapshot when they’d come in, a draw-down of station records and navigational information exactly as they’d been at the moment of their docking.

It was a convenience, only, in these tamer days. Any ship that had recently left the station for other space contained the same information, regularly uploaded on leaving one station to download at the next. It was the getting of the information immediately on arrival that was the military prerogative… because a military ship might be called to action on an emergency basis, in which event it might not have the ten or so minutes it took to receive the total update. They’d drawn a feed when they came in; and they’d draw another any time they liked. Again, military prerogative, useless to ordinary civilian ships, which couldn’t read their own black boxes: most people didn’t routinely think about it, although he was relatively sure it was no secret from station administrators that military craft did that.

At the next rest break, he passed an order to Bucklin on his own and without consulting the other captains. “Store the on-dock black-box information in the secondary box. Do a simultaneous back-up to safe-cube. Have you got that?”

“Yessir.”

“Second step. Take a daily feed from station, at the same time. Run a data comparison. Every day.”

They were alone, in the foyer of the meeting area, and Bucklin had with him a piece of electronics very hostile to bugs.

“You think they’re going to fix station records !” Bucklin asked.

“I think it’s remotely possible. Any change in archived files, I want the appropriate section leader notified and given a copy. If they try to change history or wipe a record, I want to know it. This is all a quiet matter. This Oser-Hayes is no fool. He could be doubling from Union—and Union itself has factions that might be counter to Boreale’s faction.”

“Tangled-er and tangled-er.”

“Very much so. Some faction or corporation on Cyteen Station might want Esperance to break out of the Alliance; Boreale won’t act on its own; and it’s very likely the Cyteen military will back us and the trade agreement with Pell. The result is in their interest. Their trading interests won’t universally like it. Their station-folk will. It’s far from settled, and my personal guess would be that Cyteen’s military would like it to be a done deal before Cyteen’s more complex factions find out about it: it wouldn’t be the first time they’ve acted to pre-empt their own legal process. I think Cyteen military, like that carrier back at Tripoint, wants us to get this agreement through. But Oser-Hayes doesn’t.”

Bucklin nodded. “I’ll relay that. I’ll sub in Wayne here till I get back.”

It was the first decision, JR reflected, as he watched Bucklin go to the door and call Wayne back, the first administrative decision he’d made in his new-made captaincy—one which might duplicate what someone had already ordered, but if it did, the more senior captain’s instructions would take precedence. If it conflicted, he would hear an objection. He didn’t think he’d hear one over the extravagant expense of one-write safe-cubes, which themselves were admissible in court. In the meanwhile, if that information wasn’t being collected, he wanted it. The facts were vulnerable to technicians, if to no one else, and Oser-Hayes might have cast aspersions on the honesty of the Pell-trained technicians who maintained the black-box system on Esperance, but it didn’t mean Oser-Hayes might not subvert one tech to do something about damning evidence. Like financial records.

The tone in which Oser-Hayes said Pell made it likely that distrust of the central government and of Pell was a driving force in Esperance politics.

Distrust of this place, this station, this administration was becoming his.

They’d been to the vid zoo. They’d seen all the holo-sharks at the Lagoon. That was two major amusements down on the first day.

They went to supper, in the moderately posh Lagoon, which Linda and Jeremy had both wanted, where colored lights made the place look as if they were underwater, and a sign advised that the same disposable contact lenses they’d used in the exhibit would display Wonders of the Mystic Lagoon, purchasable for a day’s wages if you hadn’t brought your own.

The junior-juniors were tired. Fletcher wanted the bubble-tub back in the sleepover. In his opinion it was time to go back to the Xanadu and settle in for the night. It was well past main-dark and the dockside, which never slept, had gone over to the rougher side of its existence: neon a bit more in evidence, the music louder, the level of alcohol in the passersby just that much higher.

But Jeremy moped along the displays, and wanted to stay on dockside a little longer. “I’m not sleepy,” he said.

“Well, I’m ready to go back,” Vince said

“We’ve got two weeks here,” Fletcher reminded them. “We agreed. Shopping tomorrow. After breakfast.”

“There’s this shop—” Jeremy said, and dived off to a curio shop on the row they walked, a crowded little place with curiosities and souvenirs on every shelf.

There were plastic replicas of Cyteen life. There were expensive plastic-encased flowers and insects from Earth. There were packets of seeds done up with pots. Grow them in your cabin and be surprised at the carnivorous flowers.

He didn’t think he wanted one of those.

They looked. They looked at truly tasteless things, and walked off the fullness of the supper on a stroll during which Jeremy ran them into every hole-in-the-wall shop on the row.

The kids bought some silly things, finger-traps, a device older than civilization, Fletcher was willing to bet. A plastic shark. Jeremy bought a cheap ball-bearing puzzle, another device that defied time. The kid was cheering up.

Good for that, Fletcher said to himself. It was worth an extra hour walking back to the sleepover if it gave Jeremy something to do besides jitter and fret.

The meeting lurched and stonewalled its way toward an adjournment for the night, the main topic as yet not on the table, and neither side satisfied… except in the fact that nothing notably budged. Aides might have carried the details forward during alterday, but there was nothing substantive to work on.

There was, by now, however, a safe-cube or two making sure that if Oser-Hayes had altered data in a record supposed to be sacrosanct, they had a record of before and after. JR was able to get to Madison without witnesses, and under security, after the meeting had broken up and while Francie and a team of discreetly armed security was making sure the Old Man, walking ahead of them, reached the chosen restaurant without crises.

“I’ve ordered analysis and safe-storage of station feed, then and now,” he said, “Daily. Bucklin’s gone to Gerald, called back personnel off leave.”

“Good,” Madison said, and by the thoughtful expression Madison shot him then, no one else had ordered it. And Madison didn’t fault his consumption of multi-thousand credit cubes or the holding of the computer security staff off a well-earned liberty. “Good move. Cube?”

“Yessir.” The sirs still came naturally. “Yes. I know what it costs. But—”

“Run an analysis. I want to know the outcome. It would be stupid of the man. But then—he’s not the brightest light in the Alliance. He might think the next passing ship would patch his little problem and no one would be the wiser. Between you and me, the system has safeguards against that kind of thing. A Pell-certified tech, under duress, would alter records quite cheerfully.”

“Knowing there’d be traces.”

“Knowing that, yes. That’s an ears-only, not even for Bucklin.Yet.”

“I well imagine.”

They walked, he and Madison together, with security hindmost, along with Alan. The restaurant wasn’t far, one of those quiet, pricey affairs the Old Man favored, randomly selected from half a dozen near the conference area.

First time in his life, JR thought, he might have gotten up even with the captains he shadowed.

“Dinner,” Madison said, “and then no rest for you and Francie and Alan. I have messages I want carried.”

The destination made sense. Immediately.

“We can’t make headway with this station,” Madison said. “So we go to the captains first. This station is begging for confrontation. They won’t like it. But I think two ships will go with us without an argument. Don’t plan on sleep tonight.”

He was supposed to approach another captain? He was supposed to carry out this end of the proposition?

It was one thing to talk in conference with the Old Man as certain back-up. It was another to walk onto another deck to persuade an independent merchanter to strong-arm a station-master tomorrow. Things could blow up. He could set negotiations back on a single failure to read signals. Or give the wrong captain information that could end up back in Oser-Hayes’ hands, or hardening merchanter attitudes against them.

But he couldn’t say no. That wasn’t why they’d pushed him ahead in rank.

If they were late-night shopping, Vince wanted a tape store. They visited that, and Vince bought two tapes. Thirty minutes, in that operation, and it was high time, Fletcher decided, to get over-active junior-juniors back to the sleepover before Linda had her way and talked him into another sugared drink that would have them awake till the small hours.

“No,” Fletcher said, to that idea.

Then Jeremy took interest in yet another curio shop, not yet sated with plastic snakes and seeds and little mineral curiosities. “Just one more,” Jeremy said. “Just one more.”

If it made Jeremy happy. If it got them back to the sleep-over with everyone in a good mood.

This one was higher class, one of those kind of shops that was open during mainday and every other alterday, alterday traffic tending to lower-priced goods and cheaper amusements. The door opened to a melodious chime, advising the idle shopkeeper of visitors, and a portly man appeared. Justly dubious of junior-juniors in his shop, that was clear.

“Just window-shopping,” Fletcher said, and the man continued to watch them; but he seemed a little easier in the realization of an older individual in charge of the rowdy junior traffic.

“Decadent,” Linda said, looking around. “Really decadent stuff.”

The word almost applied. There were plastic-encased bouquets, and mineral specimens, a pretty lot of crystals, and some truly odd geologic curiosities in a case that drew Fletcher’s eye despite his determination to keep ubiquitous junior-junior elbows from knocking into vases and very pricey carvings in the tight quarters.

Out of Viking’s mines, the label said, regarding the lot of specimens in the case, and the price said they were probably real—a crystal-encrusted ball, brilliant blue, on the top shelf; a polished specimen of iridescent webby stuff in matrix on the next shelf.

And, extravagantly expensive, and marked museum quality , a polished natural specimen on the next shelf, labeled Ammonnite, from Earth, North America. Fletcher’s study told him it was probably real.

Real, and disturbing to find it here.

He was looking at that, when he became aware Jeremy was talking to the shopkeeper, wanting something from another cabinet. He didn’t know what, in this place, Jeremy could possibly afford.

But he was amazed to see what the shopkeeper took out and laid on the counter at Jeremy’s request.

Artifacts. Pieces of pottery.

“Earth,” the shopkeeper said. “Tribal art. Three thousand years old. Bet you never saw anything like this.”

Fletcher stopped breathing. He wasn’t sure spacer kids understood what they were seeing.

But a native cultures specialist did. And a native cultures specialist knew the laws that said these specimens definitely weren’t supposed to be here.

“Real, are they?” Fletcher asked, going over to look, but not to touch.

“Certificate of authenticity. Anyone you know a collector?”

He almost remarked, Mediterranean . But a spacer wasn’t supposed to know that kind of detail.

“Got any downer stuff?” Jeremy piped up.

That got an apprehensive denial, a shake of the head, a wavering of the eyes.

Fletcher understood Jeremy’s interest in curio shops the instant he heard the word downer in Jeremy’s mouth. He bridged the moment’s awkwardness with a dismissive wave toward the Old Earth pottery and a flip of his hand toward the rest of the shop. “I always had a curiosity,” he said, playing Jeremy’s game, knowing suddenly exactly what was behind Jeremy’s new enthusiasm for curio shops and the other two junior-juniors’ uncharacteristic support of his interest in shops where they couldn’t afford the merchandise. “I read a lot about the downers. No market for the pottery. But I’ve got a market for downer stuff.”

The shopkeeper shook his head. “That’s illegal stuff.”

Fletcher drew a slow breath, considered the kids, Jeremy, the situation. “Say I come back later.”

“Maybe.” The shopkeeper went back to the back of the shop, took a card from the wall, brought it back and wrote a number on it.

“Here.”

Fletcher took the card, looked at it, saw a phone number, and a logo. “Is that where?”

“Maybe.” The shopkeeper’s eyes went to the kids, and back again.

“They’re my legs,” Fletcher said, the language of the underworld of Pell docks. “You want that market, I can make it, no question. You in?”

“See the man,” the shopkeeper said “Not me. No way.”

“Understood.” Fletcher slipped the card into his pocket

“Specialties,” the shopkeeper said.

“Loud and clear.” Fletcher shoved at Linda’s shoulder, and got her and the other two juniors into motion.

Jeremy gave him a sidelong look as they cleared the frontage, walking along a noisy dockside of neon light and small shops and sleepovers.

“Clever kid,” Fletcher said. He’d had no idea the track Jeremy had been on, clearly, in his sudden interest in curio shops.

“I said we’d get it back,” Jeremy said.

“We?”

“I mean we.”

“No.”

“What do you mean, no ? We’re on to where there’s downer stuff! This is where that guy will sell it off clear to Cyteen!”

“I mean this is illegal stuff. I mean these people will kill you. All of you! This is serious, you three. It’s not a game.”

“We know that,” Jeremy said in a tone that chilled his blood. Jeremy, Fletcher suddenly thought, who’d grown up in war. Linda and Vince, who had. All of them knew what risk was. Knew that people died. Knew how they died, very vividly.

“ Champlain’s in port,” Vince said. “So’s the thief.”

“So?” Fletcher said. “They might not sell it here. Not on the open market.”

“Bet they do,” Linda said. “I bet Jeremy’s right.”

“I don’t care if he’s right.” He’d been maneuvered all day long by three clever kids. Or by one clever kid, granted Vince and Linda might not have suspected a thing until it was clear to all of them what Jeremy was after. “This isn’t like searching the ship. Look, we tell JR. He’ll tell the Old Man and the police can give the shop a walk-through.” It sounded stupid once he was saying it. The police wouldn’t find it. He knew a dozen dodges himself. He knew how shopkeepers who were fencing contraband hid their illegal goods.

“We can just sort of walk in there and find out,” Jeremy said. “We’re in civvies, right? Who’s to know? And then we can know where to point the cops. I mean, hell, we’re just kids walking around looking at the stuff. We won’t do anything. We can find out , Fletcher. Us. Ourselves.”

It was tempting—to know what had happened to Satin’s gift, and to get justice on the lowlife that had pilfered it. They could even create a trail that could give Finity a way to come at Champlain , who had the nerve to sue them: that word was out even to the junior-juniors. He’d lay odds the crewman’s thieving had been personal, pocket-lining habit, nothing Champlain’s captain even knew about—just the regular activity of a shipful of bad habits, all lining their pockets at any opportunity. The thief had been after money, ID’s, tapes, anything he could filch; and the lowlife by total chance had hit the jackpot of a lifetime in Jeremy’s room. Sell the hisa stick, here, in a port a lot looser than Pell, a port where curios were pricey and labeled with museum quality ?

Jeremy was right. It was a pipeline straight to Cyteen, for pottery that shop wasn’t supposed to have—he guessed so, at least. Maybe for plants and biologicals illegal to have. Maybe the trade was going both ways, smuggling rejuv out to Earth, rejuv and no knowing what: Cyteen’s expertise in biologicals of all sorts was more than legend—and Cyteen biologicals were anathema in the Downbelow study programs—something they feared more than they did the easy temptation to humans to introduce Earth organisms, which at least had grown up in an ecosystem instead of being engineered for Cyteen, specifically to replace native Cyteen microbes. He’d become aware how great a fear there’d been, especially among scientists on Pell during the War, that Cyteen, outgunned and outmaneuvered in space by the Fleet, would use biologics as a way of destroying Downbelow. Or Earth. They hadn’t; but now they were spreading on the illicit route. Every scientist concerned with planets knew that.

And it immeasurably offended him that Satin’s gift might become currency in a trade that, after all the other hazards humans had brought the hisa, posed the deadliest threat of all.

Go walk with Great Sun?

Take a hisa memory into space? What could Satin remember, but a world that trade aimed to destroy for no other reason than profit and convenience?

He looked at the address of the card they’d gotten. It was in Blue. It was in the best part of Blue, right in the five hundreds. They were standing at a shop in the threes. Finity was docked at Blue 2, Boreale at Blue 5, and Champlain at 14. Being in charge of junior-junior security—he’d made it his business to look at the boards and know that information.

“Come on,” Jeremy said. “We can at least know .”

They’d had the entire ship in an uproar, looking for what wasn’t aboard; and what Jeremy had known wasn’t aboard. Now Jeremy argued for finding out where the hisa stick really was.

And maybe that in itself was a good thing for the whole ship. Maybe Finity officers could do something personally to get it back, as the kids could have a part in finding it, and maybe then the whole ship could settle things within itself.

Maybe he could settle things in himself, then. Maybe he could find a means not to destroy one more situation for himself, and to get the stick back, so he’d not have to spend a life wondering what Cyteen shop had bought a hisa memory… and to whom it might have sold it, a curiosity, to hang on some wall

“All right,” he said, suddenly resolved. “We take a look. Only a look. It’s not for us to do anything about it. We can at least look and see whether that guy back there is putting us on. Which he probably is. Do you hear me?”

“Yessir,” Jeremy said, the most fervent yessir he’d heard out of Jeremy in weeks.

“Yessir,” Vince said, and Linda bobbed her head.

“Behave,” he said severely, and took the troops toward the five hundreds.

Chapter 25

Arnason Imports, Ltd. was the name of the shop, not one of those on the front row, which Fletcher had rather expected, but one of those tucked into a nook toward the rear of a maintenance recess between another import company and a jeweler’s. It wasn’t a bad address. But it wasn’t a shop of the quality that the address might have indicated, either, and Fletcher had second thoughts about the junior-juniors, the hour—which meant an area less trafficked than it would have been in mainday. The jeweler’s was closed. The other business was open, but it had a sign saying No Retail.