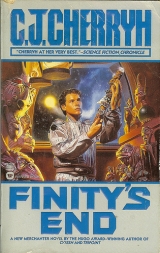

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

With cup in hand. He let go a breath. “For what?”

“For breakfast.”

He looked at his watch. For the first time. It was shift-change. Alterdawn. 1823h. And kid-bodies were justifiably hungry.

“You want breakfast?”

“Yeah,” Jeremy said. “Yessir.”

He was disreputable, in yesterday’s clothes, but he marched them into the restaurant, saw them fed.

A senior came by the table. “Board call, 0l00h tomorrow. We’re moving faster than we’d hoped.”

He thanked the senior, who was stopping at every table. 0100h was in their shift’s night. They worked two shifts and then had to scramble to make board-call.

“Tonight?” Vince said, screwing up his face. Linda slumped over her synth eggs on a bridge of joined hands. Jeremy just looked worn thin.

They’d passed out painkillers in the rest-area, and they’d taken them, preventative of the soreness they might otherwise feel, but hands still hurt, feet still stung with the cold, noses were red and chapped, and as for recreation at this port, Fletcher ached for his own bed, his own things; they’d been too tired even to use the tapes when they’d gotten into the room. The vid hadn’t even tempted the junior-juniors. Showers had, and hot water produced sleep. They’d just fallen into bed it seemed to him an hour ago.

And they had one more duty to get through, and then undocking.

At a time when they’d have been ready to fall into bed, they’d be boarding.

Twenty hundred hours and they had signatures on the line and scuttlebutt flying through Voyager corridors—as if the whole station had waited, listening, for what had become the worst-kept secret on the station: Voyager was getting an agreement with its local merchanters, with Mariner, with Pell and potentially with Union. News cameras showed up outside the restricted area where they’d held the meetings, and outside the customs zones of every starship in dock. Crowds gathered. The vid was live feed whenever the reporters could get anybody on camera to comment: it was the craziest atmosphere JR had ever seen. It scared him when he considered it, as—after a hike across the besieged docks, and attended by all the public notice outside—the Voyager stationmaster, three of the captains of Finity’s End , and three of the scruffiest freighter-captains in civilized space, along with members of Voyager Station’s administration and members of the respective crews, showed up in the foyer of the fanciest restaurant on Voyager.

The maitre d’ hastened them to the reserved dining room.

JR was well aware of their own security, who had been on site inspecting the premises even before they’d confirmed the reservation. They’d gone through the kitchens down to the under-cabinet plumbing and they were standing guard over the foodstuffs allowing absolutely nothing else to be brought in unless Finity personnel brought it.

He was linked directly to Francie’s Tech 1, who was running security on station.

He was linked to Bucklin, who was shuttling between his watch over the door and their security’s watch on the kitchen.

He was linked to Lyra, who was linked to Wayne and Parton, who were back at the Safe Harbor Inn, literally sitting in the hallway to watch the rooms.

And he was linked to Finity ’s ops, which told him they were working as hard as humanly possible to clear this port while they still had something to celebrate, and to get them on toward Esperance, where things were far less sure, and where the celebration of an agreement would not be so universal.

Maybe it was an omen, however, that from no prior understanding, the party once seated in the dining room took five minutes to arrive at a completely unified menu choice, to help out the cooks, and Finity agreed to pick up the tab.

Besides providing a couple of cases of Scotch and three of Downer wine to the ecstatic restaurant owner, who provided several bottles back again, enough to make the party hazardously rowdy with the restaurant’s crystal.

“To peace,” was the toast. “And to trade!”

There was unanimous agreement.

“We may see this War finished yet,” Jacobite said.

“To the new age,” Hannibal proposed the toast, and they drank together.

“I began my life in peace,” the Old Man said then. “I began my life in peace, I helped start the War, and I want to see the War completely done with; I want to see peace again, in my lifetime. Then I can let things go.”

There was a moment of analysis. Then: “No, no,” everyone had hastened to say, the polite, and entirely sincere, wishes that Finity would continue in command of the Alliance.

“No one else can do what you’ve done,” the Voyager stationmaster said, and Hannibal added:

“Not by a damn sight, Finity .”

The Old Man shook his head, and remained serious. “That’s not the way it should be. It’s time . I’m old . That’s not a terrible thing. I never bargained for immortality, and I can tell you relative youngsters there comes a time when you aren’t afraid of that final jump. A life has to end, and I’ll tell you all, I want mine to end with peace. That’s my requirement. All loose ends tied. I want this agreement.”

There was lingering unease.

“You’ve got it, brother,” Madison said with a laugh, and got the conversation started again, simply skipping by the statement as a given.

Madison, himself almost as old.

It was a difficult, an unprecedented moment. JR drew a whole breath only after Madison had smoothed things over, and asked himself then why the Old Man had let the mood slip, or why he’d talked about his concerns.

Getting tired, he said to himself. The captain hadn’t slept but a couple of hours last night; and even the Old Man was human.

A hard effort, they’d made, to clear this port quickly, before the two ships that had gone ahead of them had had the chance to gossip or disturb the quiet atmosphere they hoped for—

But here at Voyager, thank God, they’d found no attempt to sabotage them, not by low tech or high, not even a glitch-up at the hurried negotiations, where they’d tried to hammer out financial information, and none in refueling. Just getting the signatures on documents wouldn’t actually speed specific negotiations at Pell, Mariner, and Esperance, but it certainly put Voyager’s vote in as favoring the new system. The Voyager stationmaster, a reserved man courting a heart attack, had looked every way he could think of for a trap or a disadvantage in what they’d almost as a matter of course come to him to offer, and instead had found nothing but good for him in the deal—so much so that they’d not only gotten his agreement and that of his administration, they’d been inundated with information handed to them on Esperance. It even included things they were dismayed to be told, dealings which the Voyager stationmaster had found out, evidently, regarding the stationmaster’s affair with his wife’s sister—that tidbit of information had come out yesterday night at dinner, before the specifics of their agreement were certain, and come out with the three merchant captains present—but only one of them had been surprised.

A stationmaster who routinely had dinner with every captain willing to be treated to dinner, at Voyager’s best restaurant, certainly found out things.

Two bottles of wine administered in meetings like that, and the Voyager stationmaster probably found out things the captains didn’t even tell their next of kin.

But last night, to them, the Voyager stationmaster had named names regarding Esperance’s near bedfellowship with Union. Then the captains, at the same table, had outlined the easy operations of Esperance customs, and exactly what the contacts were by which Esperance obtained luxury goods.

And those goods shipped right past Voyager, a golden pipeline from which neither Voyager nor these captains could derive benefit. Damned right they were annoyed.

The party broke up, Jacobite’s captain actually singing on the way down the dock, the others with their respective crews headed off, God save their livers, for more drinking, probably with their crews.

They had undock coming: that saved them a breakfast invitation with the station administration. They parted company with a very delighted and only slightly tipsy stationmaster, and took their security from the restaurant’s kitchen, past a straggle of determined news cameras, newspeople asking such questions as: Can you talk about the agreement? How would you characterize the agreement ?

No information was the Old Man’s order. “Sorry,” JR had to say, to one who tried to catch him; and he hurried to overtake the rest on their walk back to the Safe Harbor.

Madison had said, in privacy after last night’s dinner, that they clearly had a worse problem ahead of them than they’d imagined, regarding Esperance, and that they might be down to using the scandal attached to the Esperance administration for outright blackmail value if things were as bad as the Voyager information intimated they were.

It had been a joke. But a thin one, even then. They had everything they wanted at three stations, and they were going to be up against profit motives with a fat, prosperous station which thought it could do whatever it pleased.

“We could turn around,” Alan said when the topic came up as they were walking back. “Let Esperance hear about the deal we’ve made so far with Sol, Pell, Mariner and Voyager, and let them worry for a year whether they’ll be included.”

“Let them hear that Sol is in the deal,” the Old Man had said, entirely seriously, as JR, walking behind with Bucklin and their security, listened in absolute quiet. “That’s their source of luxury goods, in exactly the same way and through the same connections by which it’s been Mazian’s source of matériel. So Esperance is secretly talking about merchanters long-jumping from Esperance to one of the old Hinder Star ports and getting to the new point from there without Voyager, Mariner or Pell… becoming Union’s direct pipeline to Earth. That’s still a long run. And those are big ships that have to do that run. That’s the tack we’ll take with Esperance’s local merchanters, and it’s a true argument: we’d be fine, we have the engines to make it, so we’re not talking in our selfish interest when we point out that the majority of merchanters couldn’t do it by that route. Small ships would find themselves cut out of the trade with Earth in favor only of the likes of Boreale , run from Unionside, and I don’t think our brothers and sisters of the Trade will like to hear that notion, any more than Esperance will like to hear their little scheme made public.”

“If Quen has her way,” Madison said, “more of Boreale’s class will never be built. Not by Union.”

“And if I have my way, we won’t spend those funds building Quen’s super long-haulers ourselves, either. We’ll build enough ships to keep the stations viable and building. Bigger stations, bigger populations; bigger populations, more trade. Alliance stations will never top a planetary population, but our markets are totally dependent on us—unlike Cyteen’s. Esperance will never grow grain and she’d get hellishly tired of fishcakes and yeast in six weeks, let alone six years. Which is what she’ll be down to if we pull the merchanters together again and threaten to strike if they don’t go along. We have them, cousins. They may think they’re going to doublecross us and go direct with Earth, and they may think Union’s new warrior-merchanters are going to be their answer, but we, and Quen, have that cut off.”

The Old Man, two glasses of wine in him, was still sharp and dead-on, JR said to himself. It made self-interested sense even for merchanters like Hannibal .

“We don’t want to say all of that,” the Old Man said, “at Esperance. Not until we have Union’s agreement on the line, but they’re already done for, in any ambition to become the direct Union-Earth pipeline. We just have to get them to sign the document we have. Let them do it in the theory they can doublecross us, and get Union ships in. Those ships won’t ever materialize because of Quen’s ship, and because of our agreement about the tariffs. And that means Union will define its border as excluding Esperance, because we can give Union the security and the trade it needs far better than some backdoor agreement they might make with Esperance. They’ll be left out without a tether-line. Just let drift. They don’t know that yet.” A moment of silence, just their footfalls on the station decking. Then the Old Man added: “In some regards, Mazian is the best friend we’ve got. As long as Union fears he might come back a popular hero if they push the Alliance too hard, we’ve got them , as well. Mallory wants to finish him. I prefer him right where he is, cousins, out in the deep dark, in whatever peace he’s found.”

What could you say to that? Even Francie and Alan had looked shocked.

About Madison, JR wasn’t so sure.

And for himself, he feared it was the truth.

Chapter 21

Finity’s End eased back from dock with the agility of a light load and a surrounding space totally unencumbered by traffic, even of maintenance skimmers. And the senior staff on the bridge breathed a sigh of relief to have the tie to Voyager broken.

Francie was the captain sitting, at this hour. The Old Man, Madison and Alan, the captains who’d been nearly forty-eight hours with no sleep during last-minute negotiations and subsequent celebration, were off-duty, presumably to get some rest as soon as they reached momentary stability.

But JR, with hands unblistered, face unburned, had taken Bucklin with him and made his way topside immediately before the takehold, leaving A deck matters, including the assembly area breakdown, to Lyra.

Those of them who’d drawn security and aide duty and stood guard and poured water and provided doughnuts for the on-station conferences, sixteen of the crew in all, had their own aches and had had less sleep than the captains, but they lacked the conspicuous badge of those who, also short of sleep, had done the brunt of the physical work during their two-day stay—the chapped faces and thin and hungry look of those who’d broken their necks being sure the cargo they had in their hold was what they’d bought, without any included gifts from their enemies.

Among bridge staff who’d not been involved in the meetings, Tom T. had slippers on, sitting Com with an ankle bandaged. There had been a few casualties of the slick catwalks. The Old Man had pushed himself to exhaustion, so much so that Madison had had to sub for him at the dockside offices.

JR hadn’t even tried to go to sleep in the two hours he had left before he had to report for board-call and get the assembly area rigged.

He and Bucklin had talked for a little while last night about what the Old Man had said. They’d consulted together in the privacy of his room and in lowered voices, before Bucklin had gone to his room, on the subject of their need of Mazian, and the captain’s pragmatic statement.

“He meant,” he’d said to Bucklin, desperate to believe it himself, of the man who was his hero, “that that’s until we get the Alliance in order. We need a lever.”

“You suppose,” Bucklin had said in return, “that Mallory knows what he thinks?”

Good question, that had been. And that, once his head had hit the pillow, hadn’t been a thought to sleep on, either.

If Mallory knew the Old Man was less than committed to taking down Mazian, Mallory might well have come to a parting of ways with the Old Man, and sent them off.

And if Mallory didn’t know it, and that attitude the Old Man had expressed was what the Old Man had been using as his own policy for years without saying so to Mallory, it seemed to a junior’s inexpert estimation well beyond pragmatism and next to misrepresenting the truth.

He couldn’t, personally, believe it. Mallory didn’t believe in any compromise with Mazian, and didn’t count the War ended until Mazian was dead.

Neither did he. He saw the future of his command—of all of humankind—compromised by any solution that left a still-potent Fleet lurking out in the dark. And that was a view as settled in reality as his short life knew how to settle it.

But they were bidding to make changes.

They’d shown their real manifest to Voyager Station’s agents as an earnest of good faith, as they’d insist all other merchanters do.

And, again doing what they hoped to see legislated as mandatory, they backed away from the station, leaving the mail to Hannibal , not taking trade away from that small ship, to which the mail contract was an important income; letters wouldn’t get there as quickly as if they carried them, but get there they would.

They left now having obeyed laws not yet written, having had put several hundred thousand credits into the local economy… done their ordinary business and taken on their commercial load of foodstuffs, with, JR suspected, real nostalgic pleasure on the Old Man’s part, an example of the way things ought to work.

It had been five years since they’d last called at Voyager and JR found nothing that much changed from what he remembered, unlike the vast changes at Pell and Mariner But Esperance, in every rumor yet to hit them, had made changes on Pell’s and Mariner’s scale: grown wilder, far more luxurious. Esperance had survived the War by keeping on the good side of both warring sides, irritating both, making neither side desperate enough to take action.

And by all the detail the Voyager stationmaster had told them last night and before, Esperance Station had survived the peace the same way, playing Alliance against Union far more than appeared on the surface. Smuggling hardly described the free flow of exotic goods that Esperance had offered brazenly in dockside market, only rarely bothered by customs and not at all by export restrictions: they’d known that before they heard the damning gossip from the Voyager stationmaster, regarding the conduct of the stationmaster’s office.

Esperance was going to be an interesting ride.

That was what Madison had said last night, when they all parted company. It was what nervous juniors had used to say when the ship went to battle stations. An interesting ride.

And complicating their mission, as Francie had said, among other things in that session last night, Mazian’s sympathizers and supporters, including ships like Champlain , had to have their chance to back off their pro-Mazian actions without being criminalized. Those ships had to have not just one chance to reform, but time to figure out that the flow really was going to dry up, that it wasn’t going to be business as usual, and that things wouldn’t ever again rebound back to what they had been—which had tended to be the case just as soon as the Alliance enforcers were out of the solar system.

He understood Francie’s observation. Once the small operators knew that there were new economic rules, even the majority of them would reasonably move to comply, but no one expected a ship fighting to keep itself fueled and operating to voluntarily lead the wave of reform.

Hence Finity ’s extravagant show of compliance… and that proof, via the restaurant, what their cargo was, because the persuasion most likely to convince those operators came down to a single intangible: Finity ’s reputation.

They’d gotten something extraordinary in the enthusiasm of little haulers like Hannibal, Jamaica and Jacobite . And the word would spread fast, among ships the connections between which weren’t apparent to authorities on stations.

“ We will do a three-hour burn ,” intercom announced. “ We will do a curtailed schedule to get us up to jump. It’s now 0308h. Starting at 0430h and continuing until 0730 we will be in takehold. There will be a curtailed mainday, main meal at 0800h for both shifts, then cycle to maindark at 0930h for a takehold until jump at approximately 0530 hours. We don’t want to leave our allies unattended any longer than necessary. We will do a similarly curtailed transit at the point …”

“ …and we will come in long before Esperance expects us. The captains inform us this is the payoff, cousins, this is the place we make or break the entire voyage. This is the place we came to deal with, and if we carry critical negotiations off at this station, we’ll take a month at Mariner on the return. Meanwhile we have more of those stylish, straight from the packing box work blues from Voyager’s suppliers, and more of the galley’s not-so-bad sandwiches, flavor of your choice… synth cheese, synth eggs and bacon, and real, Voyager-produced fish. Last in gets no choice. All auxiliary services will be shut down until we clear Esperance .”

“Clear Esperance ?” was the question that went through the line at the laundry, where Fletcher was in line. Toby and Ashley were on duty at the counter ahead, and as bundles came sailing in, three brand new sets of blues came out to all comers.

“He had to mean Voyager,” was the come-back to that question, but some of the seniors in line said, “Don’t bet on it,” and the intercom went on with a further message,

“ The senior captain has a message for the crew. Stand by .”

“I think he really did mean Esperance,” a cousin said glumly.

Fletcher, third from the counter as the frantic pace continued, didn’t understand what was encompassed in no services , but he had a feeling it meant more inconveniences than they’d yet seen on this voyage.

“ This is James Robert ,” the captain’s voice said. “ Congratulations on a job well done. We’re about to make up time critical to our mission. There remains the small chance of trouble at the jump-point, if by the time we arrive there has been an action between Boreale and Champlain , or if Champlain should evade Boreale and stay behind to lay an ambush. This is a canny and dangerous opponent with strong motives to prevent us reaching Esperance. Until we have reached Esperance, then, this ship will stay on yellow alert and will observe all security precautions in moving about the corridors. Expected point transit will be two hours inertial for food and systems check. Juniors, please review condition yellow safety precautions. Again, thank you for a job well done at this stopover, and I suggest you lay in supplies of packaged food and medical supplies for your quarters beyond the requirements to accommodate a double jump. We don’t anticipate a prolonged and unscheduled push either here or at the jump-point, but the contingency should be covered. Priorities dictate we evade confrontation rather than meet it. Good job and good voyage .”

It was Fletcher’s turn at the counter. He picked up clothes for himself and Jeremy as he turned laundry in, and found Jeremy at his elbow when he turned around. “Got the packets,” Jeremy said, showing a small plastic bag full, both trank and the unloved nutrient packets, as best he guessed. Jeremy was just back from the medical station.

There were a lot of the packets, of both kinds. Clearly medical had known their schedule before the announcement.

“We’re on a yellow,” Jeremy said brightly and handed him the bag with the medical supplies. “I’ll get to the mess hall, and pick up some soft drinks and some of those ration bars. They’ll run out of the fruit ones first. You want the red filling or the black?” Jeremy was already on the move, walking backwards a few steps.

“Red!” It was an unequivocal choice. They’d had them while they were working, along with the hot chocolate. The black ones were far too sweet. Jeremy turned and took off at a faster pace, down the line that was still moving along.

“Hey, Fletcher,” Connor said from the laundry line as he walked in the direction Jeremy had gone. Connor and Chad were together. “ Find it yet?”

Connor didn’t need to have said anything. Clearly the truce was over. Fletcher paused a moment and fixed Connor and Chad with a cold look, then walked on around the curve to A26.

He laid the clothes and the bag from medical on Jeremy’s bunk, and intended to put the clothes and supplies away.

But, no, he thought. Jeremy might run out of pockets, between fruit bars and soft drinks. He went out and on around to the mess hall, amid the traffic of other calorie-starved cousins, and just inside mess hall entry met Jeremy coming back, with fruit bars stuffed in his pockets and in the front of his coveralls and two sandwiches and four icy-cold drink packets in his arms.

“That should supply the Fleet,” Fletcher commented. “You want me to take some of those?”

“I got ’em. It’s fine. Well,—you could take the sandwiches.”

He eased them out of Jeremy’s arm before they flattened. The two of them started back out of the mess hall area, and met Chad and Connor and Sue, inbound.

“There’s Fletcher,” Sue said. “Tag on to the kid, is it? Who’s in charge of whom, hey?”

He could tolerate the remarks. None individually was worth reacting to. But tolerating it meant letting the niggling attacks go on. And on. And if he didn’t react to the subtle tries, they’d escalate it. He knew the rules from childhood up. He stopped.

“You’re begging for it,” he said to them in a low voice, because there were senior crew just inside, picking up their own supplies, and there were more passing them in the corridor. “I’ll take you three down to the storage and we’ll do some more hunting for what you stole, if that’s what you’re spoiling for. You two guys going to have Sue do that , too?” He’d gotten the picture how it was in that set, and all of a sudden that picture didn’t include Chad as the instigator. Not even Connor, who’d hailed him five minutes ago.

Sue was the silent presence. Small, mean, and constantly behind Connor’s shelter.

“Fletcher and his three babies,” Connor said. “Brat watch suits you fine.”

“Sue, are you the thief?”

“Fletcher.” Jeremy nudged at his arm. “Come on. Don’t. We got a takehold coming, we’ll get sent for a walk if we start trouble.”

Sue hadn’t said a thing.

“I’ll tell you how it was,” Chad said. “You did the stealing and you did the hiding, so you could make trouble. You know damn well where that stick thing is, if there ever was one.”

“The hell!”

“The hell you don’t.”

“Come on,” Jeremy said, “come on, Fletcher. Fletcher, we need to get back to quarters. Right now. People can get killed. The ship won’t wait.”

“You kept the whole ship on its ear all the way to here,” Chad said, “you made us five days late getting out of Pell, and now we’re running hard to make up. Supposedly you got robbed and you had us looking all on our rec time, and hell if you’ll do it again, Fletcher.”

“It wasn’t my choice!”

“Well, it looks that way to me!”

“Fletcher!” Jeremy said, fear in his voice. “Chad,—shut up! Just shut up! Come on, Fletcher.”

Jeremy pulled violently at his arm. Seniors were staring.

“Is there trouble here?” a senior cousin asked. The tag on the coveralls said Molly, and he’d met her in cargo, a hardworking, no-nonsense woman with strong hands, a square jaw, and authority.

“No, ma’am,” Jeremy said. “Come on . Fletcher, you’ll get us in the Old Man’s office before you know it. Come on!”

Chad and company had shut up, under an equally burning stare from cousin Molly. And Jeremy was right. There was only trouble if they tried to settle it here. He took the decision to regard Jeremy’s tug on his arm, and to walk away, with only a backward and warning glance at Chad and Sue.

Tempers were short. They were short of sleep, facing another hard couple of jumps by the sound of the intercom advisements, and Chad had re-declared their war while they’d gotten to that raw and rough-inside feeling of exhaustion, stinging eyes, aching backs, headache and the rest of it. Calm down, he tried to say to himself, no profit to a brawl.

They’d fought. And things hadn’t been notably better. Given a chance, he’d have let it quiet down, but Chad had just made him mad. Touched old nerves. It was all the Marshall Willetts, all the jealous sibs, all the school-years snide remarks and school-mate ambushes; and he had it all again on this ship, thanks to Chad.

“What’s the matter?” Vince said when he ran into them in the corridor. “Something the matter?”

“Not a thing,” Jeremy said, relieving him of any necessity to lie. Vince had gotten to looking to him anxiously at his least frown, and he felt one of those anxious stares at his back as they walked to their cabin. He was all the while trying to reason with himself, telling himself he only lost if he let Chad get to him. He and Chad had had a dozen civil words on dock-side, yesterday, when he’d misplaced the kids and Chad had been concerned. He didn’t know how things had suddenly turned around unless Chad was putting on an act.

Or unless somebody had gigged Chad into an action Chad wouldn’t have taken on his own.

They shut the door to their quarters behind them, shoved stuff in drawers, put the trank and the nutri-packs into the bedside slings first, while Jeremy started chattering about vid-games and dinosaurs.

Distraction. Fletcher knew it was. Nervous distraction as they sat down on their respective bunks and opened their sandwiches and soft drinks.

Jeremy didn’t want a fight and was trying to get his mind off the encounter.

But there was going to be a fight, and there’d be one after that, the way he could see it going. He murmured polite answers to Jeremy, swallowed uninspiring mouthfuls of the synth cheese sandwich and washed it down with fruit drink, but his mind was on the three of them back in the mess hall entry, Chad, Connor, and Sue .

That encounter, and the chance it hadn’t been Chad who’d stolen the spirit stick.

Sue was starting a campaign. He could have seen it out there, if he’d ever had his eyes on other than Chad. She meant to make his life a living hell, and Sue was a different kind of problem. Chad and Connor he could beat. But he couldn’t hit Sue and Sue had every confidence that would be the case. She had the raw nerve, maybe, to take the chance and duck fast if she was wrong and he swung on her, but she was small, she was light, he was big, and he’d be in the wrong of anything physical; damn her, anyway.

Chad and Connor had to have figured what Sue was doing. But if she was the guilty one they didn’t think so. And might not care. He was the interloper. Sue did the thinking for Connor, and Chad wasn’t highly creative, but he was the brightest mental light in that group when he finally stirred himself to take a stand.