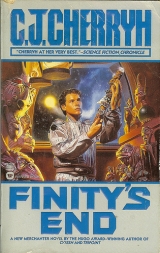

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

She had such a narrow, narrow window in which to give a civilization-saving shove at the clockwork of the system—in things gone catastrophically wrong between Earth and its colonies in the earliest days of Earth’s expansion outward. The timeliness that had brought her Finity’s End in its mission to reconcile merchanters and Union was the same timeliness that demanded the Alliance finally wake up to the economic challenge Union posed. It was the pendulum-swing of the Company Wars: they’d settled the last War, they’d banded together and shoved hard at the system to get it to react in one way; now the reactionary swing was coming back at them, the people with the simplistic solutions, and they had to stand fast and keep the pendulum from swinging into aggressive extremism on one hand and self-blinded isolationism on the other.

She hadn’t forever to hold power on Pell: a new election could depose her inside a month. People too young to have fought the War were rabble-rousing, stirring forces to oppose her tenure, special interests, all boiling to the top.

And they might topple her from the slightly irregular power she held if she’d just killed a kid. James Robert Neihart hadn’t forever to live in command of Finity’s End . He was pushing a century and a half, time-dilated and on rejuv. Mallory’s very existence was at risk every time she stalked the enemy, and she never ceased.

At least one set of hands on the helm of state were bound to change in twenty years. That was a given, and God help their successors. Madison, James Robert’s successor, was a capable man. He just wasn’t James Robert, and his word didn’t carry the Old Man’s cachet with other merchanters.

The whole delicate structure tottered. Time slowed. Finity’s End would have to wait on a teenaged boy to come to his senses… or lose him, to its public embarrassment, and her damnation, as things were running now.

And damn him, damn the kid

They lost him, the word floated through the meetings of Finity personnel on dockside, and there were quiet meetings in cafes, in bars, in the places seniors met and the junior-seniors could go, circumspectly. JR heard it from Bucklin in one of those edge-of-reputable places you couldn’t go with the juniormost juniors. The honest truth, because he couldn’t sort out how he felt about them losing Fletcher, was that he was glad it was only Bucklin with him.

All the Old Man’s hopes, he thought. To start this voyage by finally losing Fletcher…

What you want to happen, the saying went… What you want to happen is your responsibility, too. He’d heard that dictum at notable points in his life, and he wasn’t sure how he felt right now.

Guilty, as if he’d gotten a reprieve, maybe. As if the entire next generation of Neiharts had escaped dealing with a problem it could ill afford.

I will not lie. I will not cheat. I will not steal. I will never dishonor my Name or my ship…

That pretty well covered anything a junior could get into. And as almost not a junior, and in charge of the rest of the younger crew, he was responsible, ultimately responsible for the others, not only for their physical safety, but for their mental focus. If there was a moral failure in his command, it was his moral failure. If there was something the ship had failed to do, that attached to the ship’s honor, the dishonor belonged to all of them, but in a major way, to him personally.

The ship as a whole had all along failed Fletcher. His mother individually and categorically had failed him.

And what was the woman’s sin? A body that had happened to carry another Neihart life, at a time when the ship hadn’t any choice but put her ashore, because to fail the call Finity’s End had at the time hadn’t been morally possible. Finity’s End had always been the ship to lead, the ship that would lead when others didn’t know how or where to lead; and she’d had both the firepower and the engines to secure merchanter rights on the day that firepower became important, when some ship had had to follow Norway to Earth.

It was impossible to reconstruct the immediacy of the decisions that had gotten Francesca Neihart into her dilemma. It was certain that they’d had to go to Norway’s aid, and as he’d heard the story, they’d vowed to Francesca, leaving her on Pell, that they’d be back in a year.

But it had been more than that single year, it had been five; and in that extended wait, Francesca had failed, or whatever was happening to her had conspired against her sanity. He didn’t himself understand whether it was the dubious pregnancy or the overdoses of jump drugs she’d taken while she was ashore, or whether by then Francesca had just consciously chosen to kill herself.

And worse, she’d done it with a kid involved, a Finity kid, that the station wouldn’t, in repeated tries and reasoned appeals and lawsuits, give back to them.

In the sense that he was related to that kid and in the sense that he’d talked himself into accepting responsibility for that kid, he felt a little personal tug at his heart for Fletcher Neihart, his might-have-been youngest cousin who was lost down there. The three hundred six lives that Finity had lost in the War—three hundred seven if you counted Francesca, and he thought now they should—were hard to bear, but they were a grief the whole ship shared. The most had died in the big blow when the ship’s passenger ring had taken a direct hit. Ninety-eight dead right there. Forty-nine when they’d pulled an evasion at Thule. Sixteen last year. Since they’d left Francesca, half the senior crew was dead, Parton was stone blind, and forty-six more had some part of them patched, replaced or otherwise done without. Juniors had died, not immune to physics and enemy action. His mother, his grandmother, three aunts, four uncles and six close cousins had died.

So on one level, maybe those of them who’d been under fire for seventeen years were a little short on sympathy for Francesca, who’d suicided after five years ashore. But in figuring the hell the ship had lived through, maybe no one had factored in what Pell had been during those years. Maybe, JR said to himself, she’d died a slower death, a kind of decompression in a station growing more and more foreign and frivolous.

And with a son growing up part of the moral slide she’d seen around her?

Was that the space she’d been lost in, when she started taking larger and larger doses of the jump drug and getting the drug from God knew where or how, on dockside?

Out there where the drug had sent her, damn sure, she hadn’t had a kid. Or cared she had.

That was what he and Bucklin said to each other when they met in the sleepover bar, in the protective noise of loud music and cousins around them.

“The kid’s in serious trouble. Down there is no place to wander off alone,” Bucklin said, “what I hear. There’s rain going on. One rescuer nearly drowned. I don’t think they’ll ever find him.”

“Board call tomorrow,” he said over the not-bad beer. “They’re finishing loading now. Cans are hooked up.”

“They’re holding the shuttle on-world,” Bucklin said. “It’s supposed to have lifted this morning. Can you believe it? So much fuss for one of us?”

The stations didn’t grieve over dead spacers. Didn’t treat them badly, just didn’t routinely budge much to accommodate spacer rights, the way station law didn’t extend onto a merchanter’s deck. Foreign territory. Finity’s End had won that very point decades ago, with Pell and with Union.

But right now, the whisper also was, among the crew—they’d found it out in this port—Union might make another try at shutting merchanters out. Union had launched another of the warrior-merchanters they were building, warships fitted to carry cargo. The whisper, from the captains’ contact with Quen and Konstantin, was that there were many more such ships scheduled to be built.

Meanwhile Earth was building ships again, too, for scientific purposes, they said, for exploration—as they revitalized the Sol shipyards that had built the Fleet that had started the War. The whole damned universe was unravelling at the seams, the agreements they’d patched up to end the War looked now only like a patch just long enough for the combatants to renew their resources and for Union to try to drive merchanters out of business. The rumor on Pell was that of shipbuilding, too, ships to counter Union and maybe Earth.

And now cousin Fletcher had taken out running, the final, chaotic movement in a bizarre maneuver, while the finest fighting ship the Alliance had was loaded with whiskey, coffee, and chocolate she hadn’t sold at Pell, and now with downer wine.

“Luck to the kid,” JR said, on a personal whim, and lifted his mug. Bucklin did so, too, and took a solemn drink.

That was the way they treated the news when they heard it was all off, they’d not get their missing cousin.

But by board call as Finity crew who’d checked out of sleepovers and reported to the ship’s ramp with baggage ready to put aboard, they met an advisement from the office that boarding and departure would be delayed.

“How long?” JR asked their own security at the customs line, giving his heavy duffle a hitch on his shoulder. “Book in for another day, or what?”

“Make it two,” the word was from the cousin on security. “Fletcher’s coming.”

“ They found him? ” JR asked, and:

“He’s coming up,” the senior cousin said. “They got him just before he ran out of breathing cylinders. I don’t know any more than that.”

There were raised stationer eyebrows at the service desk of the sleepover when all the Finity personnel who’d just checked out came trooping back in with bag and baggage. The Starduster was a class-A sleepover, not a pick-your-tag robotic service. “Mechanical?” the stationer attendant asked.

“Unspecified,” JR said, foremost of the juniors he’d shepherded back from the dockside. The rule was, never talk about ship’s business. That reticence wasn’t mandated clearly in the Old Rules, but it was his habit from the New Rules, and he’d given his small command strict orders in the theory that silence was easier to repair than was too much talk.

“What is this?” Jeremy asked, meeting him in the hallway of the sleepover as he came upstairs. The junior-juniors were on a later call, B group. “We’ve got a hold, sir?”

There was no one in the corridor but Finity personnel. “We’ve got an extra cousin,” JR said. “They found Fletcher.”

“They’re going to hold the ship for him?”

They’d always told the juniors they wouldn’t. Ever. Not even if you were in sight of the ramp when the scheduled departure came.

“She’s held,” JR said, and for discipline’s sake, added: “It’s unusual circumstances. Don’t ever count on it, younger cousin.”

There was a frown of perplexity on the junior’s face. Justice wasn’t done. A Rule by which Finity personnel had actually died had cracked. There were Rules of physics and there were Finity ’s Rules, and they were the same. Or no one had ever, in his lifetime, had to make that distinction before. Until now, they’d been equally unbendable. Like the Old Man.

“How long?” Jeremy asked.

“Planets rotate. Shuttles lift when they most economically can.”

“How long’s that?”

“Go calc it for Downbelow’s rotation and diameter. Look up the latitude. Keep yourself out of trouble. I will ask you that answer, junior-junior, when we get aboard. And stay available!” There were going to be a lot of questions to which there was no answer, and Jeremy, to Jeremy’s misfortune, had pursued him when he was harried and out of sorts. The junior-juniors were going to have to stay on call. They all were going to have to stay ready to move, if they were on a hold. That meant no going to theaters or anywhere without a pocket-com on someone in the group. That meant no long-range plans, no drinking, even with meals, unless they went on total stand-down.

Francesca’s almost-lamented son had just defied the authorities and the planet.

Beaten the odds, apparently.

As far as the cylinders held out.

Just to the point the cylinders had run out, by what he’d heard. By all calculations, Fletcher should have died by now.

He didn’t know Fletcher. No one did. But that said something about what they were getting—what he was getting, under his command.

Pell and the new Old Rules had felt chancy to him all along. He’d felt relief to be boarding, with the Fletcher matter lastingly settled; guilty as he’d felt about that, there had been a certain relief in finality.

Now it wasn’t happening.

And nothing was final or settled.

Chapter 6

Customs wasn’t waiting at the bottom of the ramp. Police were. Fletcher knew the difference. He shifted an anxious grip on the duffle he’d been sure he was going to have to fight authority for—again—and knew the game had just shifted rules—again.

He walked ahead nonetheless, from the yellow connecting tube of the shuttle and down onto the station dock, into the custody of station police.

He didn’t know this batch of police. Many, he did know, and no few knew him by name, but he was glad he didn’t have to make small talk. He handed over his papers, a simple slip from Nunn and his shuttle authorization, and halfway expected them to put a bracelet on him, the sort that would drop an adult offender to his knees if he sprinted down the dock, but they didn’t.

“Stationmaster wants to see you,” one informed him. “Your ship’s waited five days.”

Maybe one or the other piece of information was supposed to impress him. But he’d met Stationmaster Quen far too many times at too early an age, and he didn’t give an effective damn what kind of dock charges Finity’s End was running up waiting for him. So his interfering relatives had held a starship for him. They could sit in hell for what he cared.

“Yes, sir,” he said in the flat tone he’d learned was neutral enough, and he went with them, wobbling a little. After the close, medicine-tainted air in the domes and the too-warm sterile air of the shuttle, the station air he’d thought of as neutral all his life was icy cold and sharp with metal scents he’d never smelled before. Water made a puddle near the shuttle gantry, not uncommon on the docks. The high areas of the dockside had their own weather and tended to condense water into ice, which melted when lights went on in an area and heated up the pipes.

Splat. A fat cold drop landed in front of him as he walked. It turned the metal deck plates a shinier black was all. On Pell Station it had rained, too, clean and bright gray just a few hours ago. It had been raining nonstop when he’d left, when he crossed from the van into the shuttle passenger lounge. He’d been able to see out the windows, the way he’d had his first view of Downbelow from those doublethick windows, half a year ago.

He’d rather think of that now, and not see where he was. He had no curiosity about the docks, no expectations, nothing but the necessity of walking, a little weak-kneed, with the feeling of ears stuffed with cotton. They’d stopped up in the airlock and the right one hadn’t popped yet, petty nuisance. Down at the shuttle landing, they’d given him a tranquilizer with the breakfast he hadn’t eaten. He’d had no choice about the pill. Not much resistance, either. Things mattered less than they had, these last few days.

He went with the cops to the lift that would take them out of White Sector, where the insystem traffic docked—the shuttles among them. He’d gone out the selfsame dock when he’d made the only other trip of his life, down to Pell’s World. He came back to the station that way. If nothing intervened to prevent his being transferred, he’d never use White again. He’d be down in Green, or Blue, where holier-than-anybody Finity docked, too good for Orange or Red. Fancy places. Money. A lot of money. Money that bought anything.

Anyone.

They took the lift. The lift car was on rails and sometimes it went sideways and sometimes up and down or wherever it had to take you. This time the car went through the core, around the funny little turn it did there and out another spoke of the station wheel.

Hold on, the cops told him at one point, and he dutifully tightened his grip, not arguing anything, not speaking, not looking at them.

During recent days, flat on his back in infirmary, while they dripped fluids into him and scanned his lungs for damage he half wished he’d done, he’d had ample time to realize the fix had been in before he ever ran, and to realize that his lawyers weren’t going to intercede this time. He’d sat by the window on the way up, unable to see much but the white of Downbelow’s clouds, until they put the window-shields up and stopped him seeing anything of the world. Necessary precaution against the chance tiny rock as they cleared Pell’s atmosphere. But he’d looked as long as he could.

Now, with cold and unfeeling fingers, he clung to the rail of the car while the car finished its gyrations through the station core and shot down a good several levels.

It jolted and clanked to a stop and let them out on more dockside, the cops talking to someone on their audio. They brought him out onto the metal decking, with the dark wall of dockside on one side, with its blinding spotlights and ready boards blazoning the names and registries of ships. A group of people were standing by a huge structural wall, ahead of him. One, the centermost, was the Stationmaster.

Dark blue suit, aides with the usual electronics discreetly tucked in pockets; security, with probably a fancy device or two—you couldn’t always tell about the eye-contact screens, or what the men were really looking at, but they weren’t station police, that was sure. He’d never met Elene Quen in her official capacity. He guessed this was it.

“Fletcher,” Quen said in a moderate, pleasant tone, and offered her hand, which he took, not wanting to, but he’d learned, having been trained by lawyers. When you were in something up to the hilt, you played along, you smiled so long as the authorities were smiling. Sometimes it got you more when you’d been reasonable: when you did pitch a fit on some minor point, you startled hell out of them, and consequently got heard if you didn’t also scare them.

But that wasn’t his motive right now. Right now all he wanted was not to lose his dignity. And they could take his dignity from him at any time.

“Do you have your visa?” she asked

He had. He’d expected to use it for customs. He fished it out of his coat pocket and she held out her hand for it.

She didn’t look at it. She slipped it into her suit pocket and handed him back a different one.

He guessed its nature before he looked at the slim card in his fingers. It hadn’t Pell’s pattern of stars for an emblem. It was the space-black of Finity’s End , a flat black disc for an emblem, no color, no heraldry, not even the name. The first of modern merchanters was too holy and too old to use any contrived emblem, just the black of space itself.

It was a fact in his hand. A done deal. This was his new passport

“You all right?” Quen asked him.

“Sure. No problems.”

“Fletcher…” Quen wasn’t slow. She caught the sarcasm. She started to say something and then shut it down, nodding instead toward the dockside. “They’re boarding.”

“Sure.”

“You went where you weren’t supposed to go,” Quen said, as if anything he’d done or could do had changed their intentions.

“I was invited to go.” He ought to say ma’am and didn’t. “I was coming back on my own when they found me.”

“You risked lives of your fellow staff members.”

“It was their choice to go out there. No one died.”

That produced a long silence in which he thought that maybe, just maybe, he could still throw his case back to the psychs.

“I tried to kill myself,” he said, “all right?” He knew a station, even with its capacity to absorb damage, didn’t want a suicide case walking around loose. A ship going into deep space couldn’t be happy at all with the idea. And for a moment he thought she really might send him off to the psychs and have a meeting with the ship. If he just got beyond this current try then he’d be at least eighteen by the time Finity cycled back again, eighteen years old and not a minor any longer.

“Fletcher,” Quen said, “you’re good. I’ll give you that. But you don’t score.”

She knew his game. Dead on. And he was too tired, too rattled, and too sedated to come up with another, more skillfull card.

“Yeah,” he said. “Well, I tried.”

“Fletcher, I’ve tried to help you, I’ve set you up with people where I used up favors to get you set. And you’d screw it up. Reliably, you’d screw it up.”

“Yeah, well, they’d screw it up. How about that?”

“It’s a possibility they did. But you never gave anyone a chance.”

“The hell!” he said. Temper got past the tranquilizer, and he shut it down. She wasn’t going to needle him into reaction, or salve her conscience, either. “The Neiharts aren’t going to be happy with me. You know that.”

“It’s not a place to screw up, Fletcher. There’s no place to go.—You look at me! Don’t drop your eyes. You look straight at me and you hear this. You give it a good chance. You give it a good honest try and come back with no complaints from them and after a year, in the year it’s going to take them to get back here, you can walk into my office as a grown man and say you want to be transferred back. And I’ll intercede for you . Then. Not now.”

His heart beat faster and faster. He didn’t say anything for the moment. She waited. He threw out the next challenge: “I screwed up down there. Can you fix that ?”

“I can fix it up here enough to give you a post in the tunnels. You’d work with downers. You’d stand a chance of working your way back to Downbelow.”

It was too good. It was everything handed back to him. On a platter. Everything but the downers that mattered. Years. Human years. A long time for them. Maybe too long for Melody and Patch.

“But,” Quen said, as firmly, “if you come back with anything on your record, I’ll give Finity the chance to decide whether they want you, and if they don’t, we’ll see about an in-depth psych exam to see what you do need to straighten you out. Do you copy, Mr. Neihart? Is that plain enough?”

“Yes, ma’am.” All cards were bet. Straighten you out . That meant psych adjustment , not just psych tests. It wasn’t supposedly a big deal. Just an instilled fear of sabotage was what they gave you, just a real horror of messing up the station. But they’d find out, too, what he thought of the human species. And they’d straighten that kink out of him. They’d rip the heart out of him. Make him normal, so he could never, ever want to go back to Downbelow.

“It’s serious business, Mr. Neihart. It’s very serious, life-and-death business. Are you unstable? Did you try to kill yourself?”

“No, ma’am. Not really.”

“Logical decision, was it, to run off into the outback?”

“No. But I’d duck the ship. Miss the undock. Get sent to the psychs.”

“It’d lose you your license, all the same.”

“Yes, ma’am, but you were taking it away anyway. At least I wouldn’t go on the ship.”

She thought about that a moment. She thought about him , and held his life and sanity in the balance. The noise and clang and clank of the dockside machinery went on around them, inexorable clank of a loader at work.

“That bad, is it, what we’re doing to you?”

“I don’t want them. I never wanted them. Hell if they want me.”

“Wanting had nothing to do with it, Fletcher. By putting your mother off the ship, they gave you and your mother a chance to live.”

“Well, she died and none of them did damn well by me!”

“They were kind of busy saving this station. Earth. Humanity. In which, if I do say so, they saved you. And saving the downers, if that scores with you. If the Alliance had gone under, Mazian’s Fleet would have had Downbelow for a source of supply. They’d have employed very different management methods with the downers. Or did they cover that in your history courses?”

They had. And he was glad Mazian wasn’t at Downbelow, and that someone had kept the Fleet far away. But the fact that the Neiharts were heroes in that fight didn’t mean anything on a personal level. It didn’t bring his mother back. She’d never been crazy enough the courts didn’t dump her kid back with her. And she’d never been sane enough to sign the papers that would give him up for adoption—and for Pell citizenship. He didn’t forgive her for that.

“Look at me,” Quen said. He did, reluctantly, knowing that this was the other woman largely responsible for his life—every screwed-up placement, every good, every bad: Quen had personally intervened to keep him from the trouble he’d gotten into any number of times. The fairy godmother. The magic rescue for him, that had enabled him not to compete with the likes of Marshall Willett but to stay out of complete disaster.

And the primary reason, maybe, his mother hadn’t gotten psyched-over before she killed herself. He didn’t know what he felt about Quen. He never had understood.

“I’ll tell you something,” Quen said. “You’ve got the best chance of your life in front of you. But it’s not going to be easy. You’ve walked off from every family you’ve been put with. Aboard ship, you can’t walk off; and no matter what you think, you can’t stop being related to these people. These are the real thing , Fletcher. They’re every fault you see in the mirror and every good point you own. Give them a fair chance.”

“Screw them!”

“Fletcher, get it through your head, I envy you . You’ve got a family. And they want you. Don’t be an ass about it, and let’s get over there.”

Her ship was destroyed in the War. With everybody on it. And he thought about taking a cheap shot on that score, the way she’d come back at him, but she’d held out hope to him, damn her, and she was the only hope. She gathered up her aides and her security and the cops and they all walked over to the area of the dock where the board showed, in lights, Finity’s End . There was customs; she walked him past. It was that fast. The gate was in front of him, and he looked back, looked all around at Pell docks.

Looked back, in that vast scale, even imagining the Wilsons might show up. That was his last foster-family, the one he was still legally resident with. The one he even liked.

But the dockside was vacant of anybody but dockers and, he supposed, Finity crew. Even his lawyers and his psychs were no-shows. Just Quen. Just the cops. All the little figures, dwarfed by the giant scale of the docks, were strangers.

When he gave it a second thought he guessed he was hurt—hurt quite a bit, in fact, but the lack of well-wishers and good-byes didn’t entirely surprise him. Maybe Quen hadn’t told the Wilsons where he was. Or maybe the Wilsons had heard about him running away on Downbelow, and just decided he was too crazy, too lost, too damned-to-hell screwed up.

He didn’t know what he’d say to them if they did show up, anyway. Thanks ? Thanks for trying? In the slight giddiness of vast scale and the fading tranquilizer, he hated his lawyers, hated his families. Every one of them. Even the last.

“Good-bye,” Quen told him. “Good luck. See you.” She didn’t offer her hand. Didn’t give him a chance to refuse it. “You go on up, give your passport to the duty officer. Follow instructions. You’re out of our territory from the time you cross that line.—Matter of fact, this is the ship that won that particular point of law as a part of the constitution. That was what the whole War meant. Welcome to the future.”

Screw you and your War, was what he thought as hydraulics wheezed and gasped around the gate, and the huge gantry moved above him, like some threatening dragon making little of anything on human scale. He had nothing to back up any reply to Quen. He owned no dignity but silence and to do what she’d said, go ahead and go aboard. So he left her standing and, passport in hand, took that long, spooky walk, up that ramp and into a cold, lung-hurting tunnel far thinner than the station walls.

He was aware there was black space and hard vacuum out there, beyond that yellow ribbing. Walking down the tunnel looked like being swallowed by something, eaten up alive. And it was. The cops would still be waiting at the bottom of the ramp to be sure he went all the way down this gullet; but when he reached the lock and confronted a control panel, he wasn’t even sure what to do with the buttons. They said he was spacer-born. And this damned thing had not even the courtesy of labeling on the buttons.

Hell if he was going to walk back down and ask the Stationmaster which one to push. Damn ships didn’t ever label anything. The station hadn’t labeled anything until the last few years they finally put the address signs up, because they’d been invaded once and didn’t want to give the enemy any help.

He hated the War, and here he was, sucked into a place like a step backward into a hostile time, right back into the gray, grim poverty of the War years. He resented it on that score, too.

And since nobody did him the courtesy of advising Finity he was here, he could stand here freezing in the bitter cold, or he could punch a button and hope the top one was it and not the disconnect that would unseal the yellow walkway from the airlock.

The airlock opened without his touching it.

So someone had told them he was here.

But no one was in the airlock to meet him.

He’d never seen a starship’s airlock up close, except in the vids, and it was unexpectedly large, a barren chamber with lockers and readouts he didn’t understand. He walked in and the door hissed shut. Heavily. He was in a spaceship. Swallowed alive.

Not a citizen of Pell. He never had been. They’d never let him have more than resident status and a travel visa. He knew all the ins and outs of that legality. Entitled to be educated but not to vote. Entitled to be drafted but not to hold a command. Entitled to be employed but not tenured.

Now after all his struggle to avoid it, he’d achieved a citizenship. He became aware he had a citizen’s passport in the hand that held the duffle strings, and this was where he was born to be.

But Quen hinted that, too, could change.