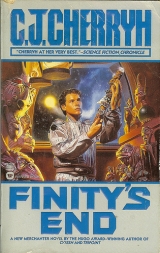

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

He had used to do long reports on downer associations. Intraspecies Dynamics, they called the forms they’d fill out, watching who worked with whom in the fields and who touched whom and didn’t touch and who chased and who ran, the experts drawing their conclusions about how all of downer society worked. Now he’d formed the picture on a different species: on how the whole junior crew worked. JR and Bucklin ran things; Lyra and Wayne assisted, and tended to sit on trouble when they found it, just the way JR directed them to do. Toby and Ashley and Nike were a set, Nike being the active force there, but they were thinkers, tech-track, not brawlers.

Sue and Connor were usually the active force in the Sue-Connor-Chad set: Sue dominated Connor and wielded him like a weapon between her and the universe; most of the time Chad just floated free, doing what he liked, generally a loner, even in a group. Chad might not even like Sue much, but she was in , and that defined things.

When Chad rose up with a notion of his own, though, Chad got in front of the three of them and used his size to protect them. Connor followed Chad when Chad chose to lead—leaving Sue to try to get control back to herself by picking their fights.

Exactly what she’d been doing. Chad had been fair-minded after their first fight, even civil on the dockside. But something had flared up out there beyond the fact they’d all worked so far past raw-nerved exhaustion they were seeing two of each other.

Sue’s mouth had been working, was his bet. But Chad was the leader in that set, a leader generally in absentia. He looked a little older, acted a little older. In the way of junior crew on Finity , he’d probably been in charge of them when they were like Jeremy and Vince and Linda. Connor hadn’t grown into his full size yet. But Chad had. Might have done so way early, by the build he had and the way he went at things: Chad didn’t fight with blind fury. Chad lumbered in with a confidence things would eventually fall down in front of him—a moment of amazement when they didn’t—that came of generally having it happen.

He’d gotten to know Chad in their process of pounding hell out of each other, to the point it had downright stung when Chad turned the accusation of theft back on him . He’d actually felt a reversal of signals, after Chad’s being a help to him on dockside, in a way that he hadn’t sorted out in the corridor—he could have lit into Chad on the spot after Chad had said it, but it wasn’t the sting of the attack he’d felt, but that of an unfair change of direction.

Sue would have had every chance anyone else had had to get into his room and take the stick, and Sue , unlike the others, might have destroyed it. Now there was trouble, and Sue kept her two cousins in constant agitation rather than letting anybody think about the theft.

“You listening to me, Fletcher?”

In point of fact, no, he hadn’t been. He’d lost what Jeremy was saying.

“About Esperance,” Jeremy said. “And the vid sims.”

“Lost it,” he confessed.

“ Takehold imminent, time’s up, cousins. Get in those bunks or wherever, tuck down for a three-hour. Don’t get caught in the shower. We’re going to put a little way on this happy ship …”

“I said I bet they have some neat sims there, I bet Union has some we’ve never seen…”

“Probably they do.” Provoke Sue to hit him, grab her and hold her feet off the deck until she got scared, maybe, but it’d be a messy, stupid kind of fight and he wasn’t anxious to make himself a target for her to kick and hit and yell. He didn’t want Sue yelling mayhem and getting the whole crew against him. Chad and Connor were going to side with her. It wasn’t damn worth it.

He had to do something when the takehold quieted down.

He mumbled a “Sure” to Jeremy’s request to borrow his downer tape, and he pulled it out and passed it to him.

By then they were one minute and counting, and he scrambled to get his own music tape set up and snugged down with him.

He had two choices. Give up, let the situation bully him into that request to get off the ship—he had the excuse he’d desperately wanted, he’d established with JR that he wanted to leave and that he was justified, and what was he doing? Now he was fighting for his place here, not to be run out. He didn’t quite know why, or how he’d come to the decision—the kid he shared this place with was the reason, he thought, but not all of it.

He’d resolved somewhere, somehow, this side of Mariner, that they couldn’t run him out like this, because it wasn’t a simple matter, his going or staying. It wasn’t even entirely Jeremy, but the complex arrangement that made Jeremy and him partners.

One thing he knew: his going or staying wasn’t going to be their choice.

He had to talk to Chad. Alone.

He had to find out whether it was Chad’s notion to take him on, or whether Chad, like him, was somebody’s convenient target.

Chapter 22

The preparation for a long, double-jump run for Esperance had the feeling of the old New Rules back again. It had the feeling of clandestine meetings in the deep dark and the chance of shots exchanged. It seemed that way to JR, at least, and touched nerves only a few months ago allowed to go quiet. People had a hurried, businesslike look at every turn.

JR sat in the relative comfort of his on-bridge post as the engines cut in and the acceleration pressed him back into the cushion. He watched the numbers tick by, and saw around him a ship in top running order; saw the unusual status on the fire panel, unusual only since they’d declared they were honest merchanters again: the weapons were under test, and the arms-comp computer was up and working on their course, laying down a constantly shifting series of contingencies.

But space was empty around them.

It was that space ahead of them they had to worry about. And in this vacancy, they were running fast getting out of system and on toward what could be ambush of military kind at the next jump-point—or of diplomatic kind at Esperance.

Three hours.

Madeleine reported in to Alan, downtime chatter in the non-privacy of the bridge, that they had the legal papers from Voyager in order. Jake’s dry, nonaccusatory report from Lifesupport suggested unanticipated change of plans was going to create havoc in his service schedules and that he was going to request that half of the type one biological waste be vented at the jump-point rather than rely on the disrupted bacteriological systems to convert it.

When the ship being under power forced a long downtime, intraship messages flew through the system– Hi, how was your stay? Missed you last night, saw a vid you’d like, found this great restaurant …

There wasn’t so much of the interpersonal chatter at Voyager. It mostly ran: I’m dead, I’ve got frostbite, I’m getting too old for this, and, I saw vids I haven’t seen in twenty years. You know they’ve got stuff straight from the last century ? At the same time, and more useful, various department heads, also idle but for the easy reach of a handheld, put their gripe lists through channels. It was a compendium of the ship’s small disasters and suggestions, like the suggestion that the long Services shutdown was going to mean no clean towels and people should hang the others carefully and let them dry.

There was one from Molly, down in cargo. JR: thought you should know. Chad and Fletcher had an argument during burn-prep. Jeremy broke it up, on grounds of ship safety. Chad accused Fletcher in the downer artifact business. Fletcher objected. All involved went to quarters for takehold. For your information .

There were six others, of similar content, one that cited the specifics of things said and added the information that it was not just Jeremy, Fletcher, and Chad, but that Sue and Connor had been there.

That built a larger picture.

There was a note from Lyra that said she’d heard from Jeff about the near-fight, but not containing the detail about Connor and Sue.

There was, significantly, no note from any of the alleged participants, and most significantly, there was none from Jeremy, who was supposed to report any problem with Fletcher directly to him.

The artifact matter was back on his section of the deck. They hadn’t time before Esperance to do another search; and the senior staff and particularly the Old Man were going to hear about the encounter, and worry about it. And that made him angry and a little desperate.

He sent back down to Lyra: The encounter between Chad and Fletcher. Who started it ?

Lyra answered, realtime: My informant didn’t say. It was in the mess hall entry, a lot of witnesses. I could venture a guess .

Don’t guess , he sent back, trying to reason with his own inclination to be mad at Fletcher for pushing it; and mad at his own junior-crew hotheads for pushing Fletcher. He didn’t know the facts, Lyra didn’t know, and the facts of a specific encounter coming from scattered reports didn’t mass enough information on the problems on A deck in general. He wished he could go to voice, for a multiple conference with Bucklin and Lyra, to see whether three heads could make any better sense of the situation with the junior crew; but ops kept jealous monopoly over the audio channels during a yellow alert, and that would be the condition until Esperance.

He keyed a query to Bucklin, instead, fired him the last five minutes’ autosave and beeped him. For Lyra:

I want you to tag Fletcher. This says nothing about my estimation of who’s in the wrong in the encounter. There’re just too many on the other side for any one person to track . He sent the I’m not happy sign, older than the Hinder Stars.

Lyra echoed it. So did Bucklin. He, Lyra, and Bucklin owned handhelds, with all the access into Finity systems that went with it; and all the accessibility of senior staff to their transmissions. Nothing in Finity command was walled off from anybody at a higher level, and there wasn’t anybody at a lower level than the juniors were. He couldn’t even discuss the theft without the chance of some senior intercepting what was going on—and he didn’t want the recurrence of the matter racketing up to the Old Man’s attention. That he couldn’t find a solution was more than frustrating: it was approaching desperation to get at the truth—and the culprit wasn’t talking.

I’m coming down there for mess , he said. It was his option, whether to be on A deck or B, and right now it sounded like a good idea to get down there as soon as the engines shut down and crew began to move about.

We could confine junior crew to quarters , Bucklin sent back.

It was certainly an idea. There was no reason junior crew had to move about during their jump-prep inertial glide. Services were shut down. There was no work to be done.

It would at least let us get clear of system , Lyra sent.

It let them keep status quo with the juniors, as far as the mass-point—where, the Old Man had warned them, senior crew might need their wits about them, with no distractions.

Good idea , he said to Lyra’s suggestion, and this time did key up the voice function, going onto intercom to every junior-assigned cabin with an official order. “This is JR,” he said. “This is a change in instructions…”

“… Junior crew is to stay in quarters until further notice. Junior officers will deliver meals to junior crew at the rest break, and I suggest you spend the time reviewing safety procedures. If you have any special needs due to the change of arrangements please indicate them to junior staff, and we will take care of them .”

“I think JR found out,” Jeremy said from the upper bunk, the ship continuing under hard push.

“Nothing happened, for God’s sake!”

“I told you!” drifted down from the bunk above.

“You told me, hell!” He recalled he was supposed to be the senior in the arrangement, and shut up, glumly so. He wished they’d get rec. Jeremy was hyped and nervous, swinging his foot over the edge with an energy he hadn’t complained of yet, but he’d been on the verge.

“You just tell them shut up, is all,” Jeremy said.

“Oh, that’d do a lot of good.”

“Well, it’s better than staring at them. They don’t like staring.”

“I don’t care what they don’t like.” He had a printout in his lap and he dragged a knee up to prop it against the force that made the page bend. “I’m reading, anyway.”

“What are you reading?”

“Physics for the hopeless,” he said. It was the manual, the long version, in the section on yellow alert. “What do they mean ‘red takeholds’?”

“They’re painted red”

“Why?”

“So you can see them. They’re all those inset hand-grips up and down the corridors, so you don’t splat all over if we move.”

“I guessed that. What’s this red alarm?”

“The klaxon. If you hear the klaxon you grab hold where you are. If it’s just a bell you have time to run to any door and bunk down, two to a bunk, or you get in the shower. If you’re carrying anything you throw it in the shower and shut the door.”

It was in the print, clearer with Jeremy’s condensed version.

“Why the shower?” Then the answer dawned on him, and he said, in unison with Jeremy: “Smaller space.”

“So you don’t fall as far,” Jeremy added cheerfully. “A meter’s better than three meters.”

“Have you ever done that?”

“Stuck it out in the shower? Yeah. One time JR and Bucklin had six in their quarters, one in each bunk, three in the shower.”

“Counting them.”

“No, Lyra and Toby snugged up on the bunk base and Toby broke his nose. Everybody was coming back from mess and the take hold sounded, and I bunked down with Angie.”

“Who’s Angie?”

“She kind of took care of me,” Jeremy said. Then added, in a slightly quieter voice: “She died.”

He’d walked into it. Damn, he thought. “I’m sorry.”

“Lot of people died,” Jeremy said. And then added with a shaky sigh: “I’m kind of tired of people dying, you know?”

What did you say? “Maybe that’s past,” he offered, best hope he could think of. “Maybe if the ship’s gone to trading for a living, then things can settle down.”

“We’re on yellow, right now.”

Jeremy’s worry was beginning to make him nervous. And he tried not to be. “Hey, we gave the Union-siders a whole bottle of Scotch. They’ve got to be in a good mood”

“I mean, you know, I didn’t think I was going to like this trading business.”

“So do you?”

“Yeah. Kind of. I didn’t think I would.”

“Neither did I. I thought being on this ship was the worst thing that could happen to me.”

“Mariner was wild,” Jeremy said with what sounded like forced cheerfulness. “Mariner was really wild.”

“Yeah,” he agreed. “It was.”

“Did you like it?”

“Yeah,” Fletcher said, and realized he actually wasn’t lying.

“I did, too,” Jeremy said. “I really did. It was the best time I ever had.”

He couldn’t exactly say that about it.

But he didn’t somehow think Jeremy was conning him, at least to the limits of Jeremy’s intentions. That ever touched him, swelled up something in his heart so that he didn’t know how to follow that remark, except to say that the time they had wasn’t over, and there wasn’t any use in their being panicked now.

“The ship doesn’t wait,” he said quietly. “Isn’t that what they said when I was late to board? The ship doesn’t wait and nothing’s ever stopped her. She’s fought Mazian’s carriers, for God’s sake. She’s not going to run scared of some skuz freighter.”

“No,” Jeremy agreed, with a nervous laugh, and sounding a little more like himself. “No, Champlain might be tough, I mean, a lot of the rimrunners are pretty good, but we’re way far better.”

“Well, then, quit worrying. What are you worried about?”

“Nothing. The takeholds and the lockdowns, this is pretty usual. This is pretty like always.” Jeremy was quiet a moment. Then, fiercely, but with the wobble back in his voice: “I’m not scared. I never was scared. I’m just kind of disgusted.”

“With what?”

“I mean, I liked the liberties we had, I mean, you know, we could go out on docks most always, and Sol Station was pretty wild.”

“I imagine it was. You’d rather be back there?”

“No,” Jeremy said faintly. “We couldn’t ever go outside Blue Sector, ever. They’d just kind of, you know, approve a couple of places we could go to, JR would, or Paul, before him. But always line-of-sight with the ship berth. Even the seniors couldn’t. They had this place set aside, we’d stay there, and we could do stuff only in Blue.”

“You mean I was conned.”

“Not ever. I mean, before Mariner that was the way it was. We got to go out of Blue a little, at Pell. Pell was pretty good. But Mariner was the best . It was really the best .”

“They’re talking about us spending a month there.”

“If it happens.”

“It’ll happen. I bet it happens.” Fletcher was determined, now, to jolly the kid out of it. “What’s your first stop? First off, when we get there, what do you want to do?”

“Dessert bar,” Jeremy said.

“For a month?”

“Every day.”

“They’ll have to rate you as cargo.”

Jeremy grinned and flung a pillow over the edge.

He flung it back. It failed to clear the level of Jeremy’s bunk. Fletcher retrieved the pillow and made two more tries at throwing it against the push.

“You’ll never make it!” Jeremy cried

“You wait!” He unbelted and carefully, joints protesting, got out of his bunk, standing on the drawers, pillow in hand. Jeremy saw him and tucked up, trying to protect himself.

“No fair, no fair!”

“You started it!” He got his arm up and slammed the pillow at Jeremy’s midsection.

“Truce!” Jeremy cried. “You’ll break your neck! Cut it out!”

“Truce,” he said, and, leaving the pillow with Jeremy, got back down into his bunk without breaking anything, a little out of breath.

“You all right?” Jeremy asked.

“Sure I’m all right. You’re the one that cheats on the V- dumps! You’re worried?”

“I don’t want you to break your neck.”

“Good. Suppose you stay in your bunk after jump, why don’t you?”

“If you don’t get up again.”

“Deal.”

He thought maybe Jeremy hadn’t expected to get snagged into that. There was silence for a while.

“Jeremy?”

“Yeah.”

“You all right up there?”

“Yeah, sure.”

There was more silence.

An uncomfortable silence. Fletcher couldn’t say why he was worried by it. He figured Jeremy was reading or listening to his music.

“So you say Esperance is supposed to be pretty good,” he said finally, looking for response out of the upper bunk. “Maybe they’ll give us some time there.”

“Yeah,” Jeremy said. “That’d be better. That’d be a lot better than Voyager. My toes still hurt.”

“You put salve on them?”

“Yeah, but they still hurt.”

“I don’t think I want to work cargo.”

“Me, either. Freeze your posterity off.”

“Yeah,” he said. The atmosphere was better then. “You got that Mariner Aquarium book?”

“I lent it.” He was disappointed. He was in a sudden mood to review station amenities. “Linda and her fish tape.”

“Yeah,” Jeremy said. There was a sudden shift from the bunk above. An upside down head, hair hanging. “You know she can’t eat fish now?”

“You’re kidding.”

“Says she sees them looking at her. I’m not sure I like fishcakes, either.”

“Downers eat them, with no trouble. Eat them raw.”

“Ugh,” Jeremy said. “Ugh. You’re kidding.”

“I thought about trying it.”

“Ugh,” was Jeremy’s judgment. The head popped back out of sight “That’s disgusting.”

The engines reached shut-down. Supper arrived fairly shortly. Bucklin brought it, and it was more than sandwiches.

It was hot. There was fruit pie.

“Shh,” Bucklin said, “Bridge crew suppers. Don’t tell anybody.”

“So why the lockdown?” Jeremy wanted to know.

But Bucklin left without a word, except to ask if they were set. And Fletcher didn’t feel inclined to borrow trouble.

They finished the dinners, tucked the containers into their bag into the under-counter pneumatic, and began their prep for the long run up to jump, music, tapes, comfortable clothing, trank, nutri-packs and preservable fruit bars.

“We’re supposed to eat lots,” Jeremy said, “if we get strung jumps.”

“You mean one after another.”

“Yessir,” Jeremy said, pulling on a fleece shirt. He still seemed nervous. Maybe, Fletcher thought, there was good reason. But they kept each others’ spirits up. He didn’t want to be scared in front of Jeremy; Jeremy didn’t want to act scared in front of him.

They tucked down for the night, let the lights dim.

In time the engines cut in, slowly swinging their bunks toward the horizontal configuration.

“Night,” Jeremy said to him.

Fletcher was conscious of night, unequivocal night, all around a ship very small against that scale.

“Behave,” he said, the way his mother had used to say it to him. “We’ll be fine.”

“Yeah,” Jeremy said. “You think Esperance’ll be like Mariner?”

“Might be. It’s pretty rich, what I hear.”

“That’s good,” Jeremy said. “That’s real good”

Then Jeremy was quiet, and to his own surprise the strong hand of acceleration was a sleep aid. There was nothing else to do. He waked with the jump warning sounding, and the bunk swinging to the inertial position.

“You got it?” Jeremy asked. “You got it?”

“No problem,” he said, reaching for the trank in the dark. Jeremy brightened the lights and he winced against the glare. He found the packet.

Count began. Bridge wanted acknowledgement and Jeremy gave it for both of them.

All accounted for.

On their way to a lonely lump of rock halfway between Voyager and the most remote station in the Alliance.

Almost in Union territory. He’d heard that…

Rain beat on the leaves, ran in small streams off the forested hills. Cylinders were failing, but Fletcher nursed them along to the last before he changed out. Hadn’t spoiled any. Hadn’t any to spare. He kept a steady pace, tracing Old River by his roar above the storm.

You get lost, he’d heard Melody say, Old River he talk loud, loud. You hear he long, long way.

And it was true. He wouldn’t have known his way without remembering that. The Base was upriver, always upriver.

Foot slipped. He went down a slope, got to his knee at the bottom. Suit was torn. He kept walking, listening to River, walking in the dark as well.

Waked lethargic in the morning, realizing he’d slept without changing out; and his fingers were numb and leaden as he tried to feel his way through the procedure. He’d not dropped a cylinder yet, or spoiled one, even with numb fingers. But he was down to combining the almost-spent with the still moderately good, and it took a while of shaking hands and short oxygen and grayed-out vision before he could get back to his feet again and walk.

He changed out three more, much sooner than he’d thought, and knew his decisions weren’t as good as before. He sat down without intending to, and took the spirit stick from his suit where he’d stashed it, and held it, looking at it while he caught his breath.

Melody and Patch were on their way by now. Feathers bound to the stick were getting wet in the rain that heralded the hisa spring, and rain was good. Spring was good, they’d go, and have a baby that wouldn’t be him.

Terrible burden he’d put on them, a child that stayed a child a lot longer than hisa infants. The child who wouldn’t grow.

He’d had to be told, Turn loose, let go, fend for yourself, Melody child.

Satin said, Go. Go walk with Great Sun.

That part he didn’t want. He wanted, like a child, his way; and that way was to stay in the world he’d prepared for.

But Satin said go. And among downers Satin was the chief, the foremost, the one who’d been out there and up there and walked with Great Sun, too.

He almost couldn’t get his feet under him. He thought, I’ve been really stupid, and now I’ve really done it and Melody can’t help. I’ll die here, on this muddy bank.

And then it seemed there was something he had to do… couldn’t remember what it was, but he had to get up. He had to get up, as long as he could keep doing that.

He went down again.

Won’t ever find me, he thought, distressed with himself. It must be the twentieth time he’d fallen. This time he’d slid down a bank of wet leaves.

He tried to get up.

But just then a strange sound came to his ears.

A human voice, changed by a breather mask, was saying, “Hey, kid! Kid!”

Not anymore, he thought. Not a kid anymore.

And he held onto the stick in one hand and worked on getting to his feet one more time.

He didn’t make it—or did, but the ground gave way. He went reeling down the bank, seeing brown, swirling water ahead of him.

“God!” A body turned up in his path, rocked him back, flung them both down as the impact knocked the breath out of him. But strong hands caught him under the arms, saving him from the water. There was a dark spot in his time-sense, and someone sounded an electric horn, a signal, he thought, like the storm-signal.

Was a worse storm coming? He couldn’t imagine.

Hands tugged at the side of his mask. His head was pounding. Then someone had shoved what must be a whole new cylinder in, and air started getting to him.

“It’s all right, kid,” a woman’s voice said. “Just keep that mask on tight. We’ll get you back.”

The woman got him halfway up the slope. A man showed up and lifted, and he finally got his feet under him.

He walked, his legs hurting. He hung on one and the other of his rescuers for the hard parts, and drew larger and larger breaths, his head throbbing from the strain he’d put on his body.

They got him down to a trail, and then someone had a litter and they carried him. He lay on it feeling alternately that he was going to tumble off and that he was turning over backwards, while Great Sun was a sullen glow through gray clouds and the rain that sheeted his mask. It was hard going and his rescuers didn’t talk to him. Breathing was hard enough, and he figured they’d have nothing pleasant to say.

By evening they’d reached the Base trail and he realized muzzily he must have been asleep, because he didn’t remember all of the trip or the turn toward the Base.

Somebody waked him up now and again to see that he was breathing all right, and he had two cylinders, now, both functioning, so breathing was a great deal easier, better than he’d been able to rely on for the days he’d been out.

Satin didn’t want him. Melody didn’t want him…

The bottom dropped out of the universe. He was falling. Falling into the water. He fought it.

Second pitch. It was V -dump. He wasn’t on Old River’s banks. He wasn’t suffocating. He was on a ship, a million—million klicks from any world, even from any respectable star.

His ship was slowing down, way down, to match up with a target star. They were all right.

No enemies. They’d have heard if there’d been enemies.

Finity’s End was solidly back in the universe again, moving with the stars and their substance.

He opened his eyes. Lay there, fumbled open a nutri-pack and sucked it down, aware of Jeremy rummaging after one.

“You all right?” he asked Jeremy.

“Yeah, fine.”

He saw Jeremy had gotten his own packet open. The intercom gave an all-clear and told them their schedule. They had two hours to clean up, eat, and get back underway.

He lay there, thinking of the gray sky spinning slowly around above the treetops. Of rain on the mask. Of the irreproducible sound of thunder on the hills.

The room smelled like somebody’s old shoes. And two nutri-packs down, he found the energy to unbelt and sit up.

“Shower,” he said to the kid, as Jeremy stirred out of his bunk. “Or I get it.”

“You can have it if you want,” Jeremy said.

“No, priority to you.” His stomach hadn’t quite caught up. He had an ache in his shoulders. Another in his heart. “Three hours at this jump-point. We’ll both make it.”

“Yeah, we’re going to make it,” Jeremy said, and hauled his skinny body out of the bunk. “No stinking Mazianni at the point, we’re going to get to Esperance and the Old Man’s going to be happy and we’ll be fine .”

“Sounds good to me,” he said, and while Jeremy went to the shower, he got up, self-disgusted, out of a bed that wanted changing, in clothes that wanted washing. He dragged one change of clothes out of the drawer, wished he had a change of sheets. He got out one of the chemical wipes and wiped his face and hands. It smelled sharp, and clean.

He could remember the stale smell of the mask flinging his own breath back at him. He could remember the fever chill of the earth, and the uneven way his legs had worked on the way home.

And Satin’s stick in his hand. He’d refused to let go of it. He’d said, “Satin gave it to me,” when the rescuers questioned him, and that name had shaken them, as if he’d claimed to have seen God.

He was here . He was safe.

He’d clung to the stick during that rescue without the remotest notion what to do with it, or what he was supposed to do.

Satin, in that meeting, had seen further into his future than he could imagine. She’d been in space. She knew where she sent him.

But he hadn’t known.

He sat on the edge of his bunk, listening to the intercom tell them further details, where they were, how fast they were going, numbers in terms he didn’t remotely understand.

But he was safe. He’d come that close to dying, and he sat here hurtling along in chancy space and telling himself he was very, very lucky; and, yes, beyond a doubt in his mind, now, Satin had sent him here. Satin, who’d known the Old Man.

He wondered if Satin had had the faintest idea he was a Neihart, or why he was on her world, when she’d sent him into space. He’d never from his earliest youth believed that downers were as ignorant as researchers kept trying to say they were. But he’d never attributed mystical powers to them: he was a stationer, too hard-headed for that—most of the time.

But underestimate them? In his mind, the researchers often did.

And in his dream and in his memory Satin had known his name.

Satin had known all about him.

She’d not gotten that from the sky. Sun hadn’t whispered it to her. She’d talked to Melody and Patch.

And knowing everything hisa could remotely know about him, she’d sent him… not to the station. To his ship . Had she known Finity was in port? Had she known even that, Satin, sitting among the Watcher-stones, to which all information flowed, on quick downer feet?

Satin, who perhaps this moment was sitting, looking up at a clouded sky, and, in the manner of an old, old downer, dreaming her peace, her new heavens, into being.