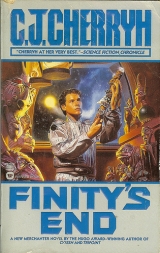

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“No.”

“I don’t think it’s her job, either. No more than it’s your job to run her planet for her.”

“I never said it was.”

“You have to take that line if you want to be an administrator. You have to work with the committee, play with the team, and leave the downers alone. If the committee had found out what you were doing they’d have had you on a platter, and by now they probably do know and they’ve got three study groups and a government grant to try to find out what happened. You were doomed. They’d have had you out of that job in a year.”

“It wouldn’t have gone the way it did.”

“Yes, it would. Because you questioned the most basic facts in the official rulebook… that Satin’s people have to be left alone and her people can’t learn anything they don’t think of for themselves. Those are the rules, Fletcher. Defy them at your own risk.”

“I never risked them .” It was the one thing he could say, the one thing he was, in heart and head, sure of, that Nunn never would believe.

“I know that. I know that. And Satin won’t talk to the researchers. Not to the researchers. Not to the administrators. Do you think she’s stupid? She has nothing to say to them.”

“What do you know? You talked to her once”

“Like you. You talked to her once.”

“I’ve studied them all my life. I do know something about them.”

“Something the researchers don’t know?”

It sounded ludicrous. He was no one. He knew nothing.

“You love them?” the captain asked. That word. That word he didn’t use.

“Love isn’t on the approved list. Ask the professors.”

“I’ll give you another radical word. Peace , Fletcher. It’s what Satin’s looking for. She doesn’t know the name of it, but she went back to the Watchers to wait for it. That’s why she’s there. That’s why she folded downer culture in on itself and gave not a damn thing to the researchers and the administrators and all the rest of the official establishment. It was her dearest wish to go to space. But we weren’t ready for her.”

“Satin went back to her planet rather than put up with the way we do business!” Fletcher said. “Wars and shooting people on the docks didn’t impress her. And she didn’t like the merchant trade. Downers give things, they don’t sell them.”

“When you met her, what did she tell you?”

His voice froze up on him. Chills ran down his arms. Go , she’d said. For a moment he could hear that soft, strange voice.

Go walk with Great Sun.

“We talked about the Sun. About downers I knew. That was all.”

“Peace, Fletcher. That’s the word she wants. She knows the word, but we haven’t yet shown her what it means. She knows that the bad humans have to leave downers alone. But that’s not peace. We haven’t been able to show it to her. We showed her war. But we never have found her peace. And that’s what we’re looking for, right now. On this ship. On this voyage”

“Fancy words.”

“Peace is a lot more than just being left alone.”

“You couldn’t give it to her down there,” the Old Man said. “You’re a child of the War. So is JR.” His eyes shifted beyond Fletcher’s shoulder, to a presence he keenly felt, and wished JR had heard nothing of this. “Neither of you have any peace to give her. And where will you get it, Fletcher? Your birthright is this ship . This ship, that’s trying to make peace work realtime, in a universe where everybody is still maneuvering for advantage mostly because, like you, like Jeremy and his generation, even like Quen at Pell, you’re all too young to know any better. You’re as lost as Satin. You don’t know what peace looks like, either.”

“What do you know about me or her? What the hell do you know?”

“The hour of your birth and the prejudice of several judges. The fear and the anger that sent you running out where you knew you could die… we never wanted you to be that afraid, Fletcher, or that angry.”

“You don’t want me! You wanted your fourteen million! And I was happy until you screwed up my life! Besides, I wasn’t trying to kill myself.”

“But if you hadn’t run out there, Satin would have come to the end of her life without talking to Fletcher Neihart.”

“What does that have to do with it?”

“Nothing, if you don’t do anything. A great deal if you commit yourself to find out what peace is, if you learn it, if you find it and take it to your generation. Satin’s still looking at the heavens, isn’t she? Still waiting to see the shape of it, the color of it, to see what it can do for her people, Fletcher. Right now only a few of us remember what peace looked like, tasted like, felt like.”

He caught a breath. A second one. He’d never been up against anybody who talked like James Robert. Everything you said came back at you through a different lens.

James Robert did remember before the War. Nobody he knew of did.

“Work for this ship,” he said in James Robert’s long silence. “Is that what you mean? Do the laundry, wash the pans…”

“All that we do,” James Robert said, “keeps this ship running. I take a turn at the galley now and again. I consider it a great pleasure.”

“Yes, sir.” He knew he’d just sounded like a prig.

“What good were you at laundry anyway? You think the first strike happened at Olympus.”

“Thule, sir.”

“Good. Details matter. If it wasn’t Thule everything would have been changed. The borders, the ones in charge, the future of the universe would have been changed, Fletcher. Details are important. I wonder you missed that, if you’re a scientist.”

“Biochemist.”

“Biochem? Biochem isn’t related to the universe?”

“It is, sir. Thule.”

“Precisely. I detest a man that won’t know anything he doesn’t imminently have to. Just plod through the facts as you think you know them. ‘Approximate is good enough’ makes lousy science. Lousy navigation. And keeps people following bad politicians. Are you a rules-follower, Fletcher?”

The Old Man was joking with him. He took a chance, wanting to be right, aware JR was measuring him and fearing the Old Man could demolish him. “I think you have my record, sir.”

A small laugh. A straight look. “A very mixed record.”

“I’m for rules, sir, till I understand them.”

“I knew your predecessor,” the Old Man said. “There’s a similarity. A decided similarity.”

He hoped that was a compliment.

“So JR tells me he’s assigned you to keep young Jeremy in line.”

“Jeremy’s been keeping me in line, mostly.”

A ghost of a smile. And sober attention again. “Biochem, eh?”

He saw the invitation. He didn’t know whether he wanted it. James Robert had a knack for getting through defenses, with the kind of persuasion he wanted to think about a long time, because he’d gotten his attention, and told him the truth in a handful of words, the way Melody had, once: you sad .

James Robert told him plainly what he’d always seen about the program: that if you didn’t believe what they said, follow their rules, you were out. And he’d hedged it all the way, being new, following his dream, living his imaginings… not looking at…

Not looking at what James Robert told him, that the Base wanted someone like Nunn, someone who’d follow rules, not push them—because what ran the human establishment on Downbelow wasn’t on Downbelow. It was on Pell.

“You get a few ports further,” the Old Man said. “We’ll talk again. You have a good time in this one, that’s my recommendation.”

The Old Man hadn’t ever mentioned the fight. The hazing. Any of it. Or changed JR’s assignment of him.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “I’ll try to. Thank you.”

The Old Man nodded. JR opened the door, let him out.

And came outside with him.

“Fletcher,” JR said.

He turned a scowling look on JR, daring him to comment on personal matters.

“I didn’t set you up to fail,” JR said. “Any help you want, I will give you.”

“Thank you,” he said. He couldn’t beg JR to forget what he’d heard. He had to leave it on JR’s discretion, whatever it might be, without trusting it in the least. He left, back to the laundry, thinking… they’d talked about peace , and he’d believed everything the Old Man said while he was saying it. It gave him the willies even yet, when he considered that this ship hadn’t been trading for a living for seventeen years.

The Old Man said they were looking for peace, and that none of them knew what it looked like.

He thought of Jeremy, talking of going to Mallory, carrying on the fight. Of Jeremy, shivering in the bunk approaching jump, because the kid was scared .

The youngest of them had seen the least of what the Old Man said they were looking for. They called it peace , when the Treaty of Pell had stopped Union from going after the former Earth Company stations, when the stations agreed to host the Merchanters’ Alliance and Earth disavowed the Fleet… but the Fleet hadn’t surrendered. And there wasn’t any peace.

And the oldest downer had gone back to her world to watch the heavens and believe for her people.

Believing that there was something more, though she’d seen what war looked like. Believing there’d be something else—when for thousands upon thousands of years the Watcher-statues had watched the heavens, waiting…

For what? Visitors?

What peace ? he should have asked the Old Man when he had the chance. What does this ship have to do with it, when all it’s done is fight? What are we doing, when you say we’re looking for peace? None of the juniors know what it is, for very damn sure .

When did I say yes? When did I even start listening ?

Anger tried to find another foothold. Resentment for being conned.

But this was a ship that had meant important things in the recent past.

What if? he began to ask himself. He, who’d met Satin, and looked into her eyes.

“Got chewed out, hey?” Vince asked when he got back to the laundry, and he just smiled.

“No,” he said in perfect good humor. “I just got put in charge of you three.”

Vince’s mouth stayed open. And shut.

“You’re kidding,” Linda said.

“No,” he said. Jeremy grinned from ear to ear.

Chapter 15

Liberty was coming. The mood all over the ship was excitement, anticipation. The junior-juniors’ attention for anything was scattered: liberty and stationside and games were coming after days of duty and sticking by their posts.

It was, Fletcher thought as the ship prepared for docking, air to breathe—wider spaces, not corridors, not the unsettling pervasive thrum that he’d grown used to and that he now knew was the ring in its constant motion. Where they’d exit in less than an hour wasn’t going to be Pell, but it was a place that would look like Pell, feel like Pell, be like Pell. He could do things ordinary people did on stations, walk curves less steep than Finity ’s deck—go to a shop, look at tapes. Maybe buy one. He was due a little money, a little cash, they’d said, for incidentals. If he skipped a meal or two, he could buy a tape.

A third of personnel, including the bridge, and older crew, whose personal quarters were in areas that would be downside during dock, could simply sit in quarters during docking and undock, if they chose to do that. For the seniormost crew not so blessed by the position of their cabins during ring lock-down, there was the small theater topside, where a pleated floor (Jeremy had explained this wonder of engineering), solid seating and safety belts were available. The whole theater became stairsteps.

But for the able-bodied, they packed them into rec like sardines, and they rode it through with takeholds and railings, just the way they’d done in undock. The junior-juniors disdained the theater. Jeremy said docking was more fun than undock.

Fletcher secretly wished they’d offered him a theater seat with the ship’s oldest. But, with Jeremy, he went down the corridor with his duffle, joining all the other crew doing the same thing. There was a chute, Jeremy had forewarned him, where you sent your duffle down to cargo; your baggage would meet you on the docks. It was why you tied silly personal items to your duffle strings and had your name stencilled in large letters. His was just what he’d boarded with, plain, distinctive only in that it wasn’t worn and stencilled. He’d put a ship’s tag on it, Jeremy’s recommendation. He’d tied a bright civvy sock to the tag strings, the only thing he owned amenable to serving as ID. He’d not brought anything in his baggage but clothes and toiletries. And watching the way the duffles went down the chute he was glad he’d packed nothing else.

“They’re not damn careful,” he said.

“Warned you,” Jeremy said brightly, “They’re more careful coming back. That’s the good thing. They know the incomings got fragiles.”

The rec hall was transformed again. Machines and tables were out. The safety railings were back. He and Jeremy stood, indistinguishable from the mob of other silver-suited Finity crew, Linda and Vince each with senior crew protectively spaced between them as Finity glided toward dock and occasional decel forces shoved gently at the ship.

“ Decoupling, ” the intercom said. “ Condition yellow take hold .”

That meant real caution. Next thing to Belt-in-if-you-can. Don’t let go to scratch your nose.

Gravity ebbed. Fletcher’s stomach went queasy. Don’t let me be sick. Don’t let me be sick. It’s nerves. It’s just nerves. Nothing out of the ordinary’s going on .

“ Condition red take hold. ”

“Hold on tight,” Jeremy said.

Big jolt. Not too bad, he thought.

Then a giant’s hand grabbed them and suddenly slung everyone in the room hard against the rails with a crash and a bang that echoed through the frame.

No one came loose. No one screamed. Fletcher thought his sore fingers had dented the safety rail and his neck felt whiplash.

“That was the grapple,” Jeremy said cheerfully, on the general exhalation and mild expletives in the room, and added, “We’re carrying a lot of mass.”

“I could live without that.” Fletcher congratulated himself he hadn’t screamed. His stomach was the other side of the wall. Jeremy had let go the rail to stretch his back. “We didn’t hear an all clear.”

“We will,” Jeremy said in cocky self-assurance, and in the very next instant the intercom came on to give it:

“ The ship is stable. We are in lock. Mainday three to stations. ”

Jeremy constantly scanted the rules. Fletcher had begun to notice that small defiance of physics and warnings. Jeremy was confidently just ahead of everything; he’d taught him some of his unsafe habits, which he knew, now that he’d actually seen the written regulations for himself. And one part of Fletcher’s soul said the hell with it, the kid knew, while another part said that since he was nominally in charge he ought to call the kid on it…

In a system the kid knew from before his birth.

He had his instructions from JR, all the same. Yesterday at shift-end a brand new bound print of ship’s rules had arrived in his quarters, a gift which Fletcher acknowledged to himself he’d have chucked in the nearest waste chute a day ago in disdain of the whole concept. Instead, knowing he had Jeremy to oversee, he’d fast-studied it and memorized the short list in the front; he had it in his duffle, and meant business. He’d advised the junior-juniors so: he’d take no shots from the Old Man due to their putting anything over on him.

“ Section chiefs report forward for passport procedures .”

“There you go,” Jeremy said.

Jeremy not only hadn’t resented his appointment over him, the kid had actually seemed to take pride in it—as well as in the fact he’d gotten that rise in rank directly after the rough Welcome-in, when he’d, as Jeremy so delicately put it, knocked the fool out of Chad.

“Meet you out there,” Jeremy said as he extricated himself from the row of cousins. He felt a pat on his back, a pat from other, older crew as he passed them to get to the door… they knew he’d gotten an assignment, and they encouraged him. Him , the outsider.

He made the door in a flutter-stomached disorganization, telling himself, without feeling of his pocket, that, yes, he had his passport, and Jeremy’s and Vince’s and Linda’s, for which he was responsible.

He joined the other section chiefs, far senior, over sections far more important to the ship. It was simply his job to get the junior-juniors through customs and to get them back through customs on the way out. To save long lines when there was no particular customs slow-down, section chiefs handled passports, ID’ed their people for customs in a mass, and passed them through; but junior-juniors, being minors, didn’t handle their own passports at any time. He had to. In the sleepover, being minors, they didn’t sign their own bills.

He had to sign for them. He had to authorize expenses for the junior-juniors, and he was to dole out credit in a reasonable way for pocket change, but meal and authorized purchase bills went to his room. He’d thought it was a watch-the-kids kind of baby-sitting JR had handed him. It had turned out to have monetary and legal responsibilities attached. A lot of money. Several thousand c worth, that he was supposed to dispense and account for.

There’d been a visicard hand-clipped to the front of the manual, a quick and easy condensation of the rules, specific advisements for this port, even a good fast study for the arcane procedures of getting into a sleepover—one of those dens of iniquity stationers viewed as exotic and dangerous and about which teenaged stationers entertained prurient curiosity. He was going to such a place with a parcel of apparent twelve-year-olds forbidden to drink or to consort with strangers. He took the card out of his breast pocket, thumbed the display on and double-checked it while the line advanced another set of five, right down to his group.

Phone the ship with your sleepover address code and enter it into your pocket com first thing after registering and reaching your room. Do not carry cash chits above 20 c at any time. Memorize the date and hour of board-call and report no later than one hour before departure. If you overnight in another sleepover, phone the ship. If injured or ill phone the ship. If arrested, phone the ship. Note: White dock is off-limits to all deep-space personnel by local statute. Junior personnel are limited to Blue and Green by order of the senior captain. The senior staff reminds the crew that this is a tight port with strict zoning. In past years, we have had military privilege. That is not in force now. Be mindful of local regulations. Have a pleasant stay.

Sleepover rules and do’s and don’ts were in the next screen. Third screen provided a crewman other specific procedures in case of disaster, how to avoid getting left here by his ship.

His ship. God. His ship . His independence was gone. He’d begun to rely on his ship . He looked no different than the rest of them. His uniform made no distinction of rank: he wore silver coveralls, with the black patch that had no ship-name beneath it. They were instructed, all of them, the manual said, to write simply spacer if asked for rank on any blank the station handed them, as even the captains did, despite stations wanting to know more than that about the internal business of merchanters, and wanting, historically, to regulate them. Some ships complied. But spacer and Neihart was enough for the universe to know.

Arrogant. Stationers called Finity that.

At least, for his peace of mind, Finity personnel had booked a block of rooms close together in the same sleepover. JR had told him personally no drinking on station, and with the kids in tow and with Vince to keep an eye on, it seemed a good idea. JR hadn’t told him don’t go sleep with any chance stranger who walked up on him… but he had very soberly figured it out for himself that that practice of free sex which so scandalized station-dwellers was not a good idea for him, not in a situation the rules of which he was desperately studying, and not with three kids he was responsible for getting back in one piece, and not with strangers whose motives he could guess far less than he could guess those of his shipmates.

The airlock cycled them through, letting them out into the cold yellow passage to the station airlock, and through to the elevated ramp.

All the docks spread out in front of him from that vantage, the neon lights of unfamiliar shops and establishments displaying an unfamiliar signage above the heads of his fellow Finity spacers as they walked, down, down, down to the cordoned area with the small customs kiosk.

He’d seen this procedure all his life… looking up, from the other end of the proposition, standing, say, by one of the big structural pillars, watching the arrival of a ship. This time he was one of the distant visitors, the customers, the marks to some, the fearsome strangers to others.

The scene inside the airlock wouldn’t be mysterious to him, now. Ever. He knew the routines, he knew the names of the people around him—and this station didn’t know his name or have him in its records. No one on this station knew who he was except as Finity crew, no one would answer familiar phone numbers. His station looked exactly the same—but at home there was a neon Kittridge’s Bar sign opposite Berth Blue 6. Here it was the sign for Mariner Bank.

The shift and counter-shift of perspectives as his feet touched the dock itself had him halfway numb. But he resolved not to gawk at the signs, not even to think about them, for the sake of the butterflies holding riot in his stomach. He waited his turn and reported his own small team through customs and registry as Finity juveniles on liberty, four, counting himself.

Hands only moderately trembling—he’d feared worse—he slipped the passports through the scanner, a modest number compared to what section chiefs in Engineering had to present. Jake from Bio had a stack of passports, as a customs officer read off James Thomas Neihart, James Robert Hampton-Neihart, Jamie Marie Neihart, Jamie Lynn Neihart , and proceeded to June and Juliana in a patient, mind-numbed drone. His agent handed him slips with each passport, slips that said—he looked when he had walked clear of the line, still within Finity ’s customs barriers– The importation or export of radioactive materials, biostuffs and biostuff derivatives including genetic mimes is strictly controlled.

He’d been among the last crew chiefs. JR came behind him and, as he supposed, took the senior-juniors’ passports through the kiosk; by the time the airlock spilled out JR’s bunch, his own three crew members were already lugging their duffles down the ramp. The press of Engineering midlevel crew had largely cleared out; there was still a crowd at the crew baggage chute.

Bucklin walked past him, paused and slipped two messages into his hand. Fletcher looked at them, mildly surprised, thinking one at least, maybe both, were from JR. But one had Finity ’s black disc for a source, that was all. He read the first slip as Bucklin walked away.

From the senior captain. Jr. Crew Chief Fletcher R. Neihart , it said. The senior officers extend good wishes and willing assistance in the assumption of your new duties. Should you have any need of assistance do not hesitate to call senior staff .– James Robert Neihart ,

He read it twice, first assuming it was routine, and then suspecting it might not be and looking for meanings between the lines. It’s your call was what he saw on that second reading. Call too early and you’re incompetent; call too late and you’re in my office .

Maybe he was too anxious. Maybe it was just a routine letter and a computer had done it, the same way a computer called their names for duty assignments.

The other message was a sealed letter. He pulled the edges open. A credit slip was inside.

Two credit slips. A pair of 40 c slips made out to him. Wrapped in a note. No young person should go on first liberty without something in his pocket. Don’t spend it unless you find something totally foolish. This is personal money. Allow me to act like a grandmother for the first time in years .– Love. Madelaine .

He didn’t want charity. He didn’t want Madeline’s money, personal or otherwise, even if 80 c had to be a trifle to her personal wealth.

Grandmother.

And Love? Love, Madelaine ? Her daughter was dead. Her granddaughter was dead. Allow me to act like a grandmother …

A lot of death. How did he say No thank you?

How did he avoid getting in her debt? How dared she say, I love you , his great-grandmother, who didn’t know damn-all about him.

And who knew more than anybody else aboard.

He pocketed the money with the messages, told himself forget it, enjoy it, spend it, it wasn’t an irrevocable choice and money didn’t buy him, as he was sure Madelaine didn’t think it did—Say anything else about her, the woman wasn’t that shallow and it was just a gesture.

“Fletcher!” he heard, Jeremy’s voice, and in a moment more Vince and Linda rallied round. “We got to get our bags!” Jeremy said.

They walked over where baggage was coming out the conveyor beside cargo’s main ramp. The cargo hands, family, were tossing duffles to cousins who were there to claim them, and Jeremy snagged all four in short order, for them to take up.

“Where do we go?” Linda wanted to know. “Where, where, where have they got us? What’s the number?”

“We’re all at the Pioneer,” Fletcher said. “It’s number 28 Blue, that way down the dock.” He pointed, in the smug surety of location that came with knowing they were docked at berth number 6 and the numbers matched.

“They got a game parlor at number 20,” Vince said, already pushing. “It’s on the specs. I read it. There’s this high-gee sim ride. It’s just eight numbers down. We can go there on our own…”

“The aquarium,” Jeremy reminded him.

“Who wants stupid fish?” Linda asked “I don’t want to look at something I’ve got to eat!”

“Shut up! I do!”

“Game parlor this evening,” Fletcher said “First thing after breakfast, the Mariner Aquarium, all three of you, like it or not. Vids in the afternoon, and the sim ride, if I’m in a good mood.”

“You’re not supposed to go with us,” Vince said. “Go off to a bar or something. You can get drinks. We won’t say a word. Wayne did.”

“Find JR and complain,” Fletcher said. He heard no takers as he shepherded his flock past the customs kiosk, a wave-through, as most big-ship arrivals were.

JR was even in the vicinity, with Bucklin and Chad and Lyra, as they cleared customs, and he didn’t notice Vincent or Linda lodging any protest.

You know stations , JR had said in his brief attached note, explaining the general details of his duties and telling him the name and address of the sleepover they’d be staying in. It gave him something to be, and do, and a schedule, otherwise he foresaw he was going to have a lot of time on his hands.

He’d also been sure at very first thought that he didn’t want to consider ducking out or appealing to authorities or doing anything that would get him left on Mariner entangled in its legal systems. That was when he’d known he’d settled some other situation in his mind as a worse choice than being on Finity , and that a grimly rules-conscious station one jump from where he wanted to be was not his choice.

So, amused, yes, he’d do JR’s baby-sitting for him, grudgingly grateful that he was shepherding Jeremy and not the other way around. And JR’s statement you know stations went further than JR might expect. He knew Pell Station docks upside and down. He knew a hundred ways for juveniles to get into trouble even Jeremy probably hadn’t even thought of, like how to get into service passages and into theaters you weren’t supposed to get to, how to bilk a change machine and how to get tapes past the checkout machines without paying. He hadn’t been a spacer kid occasionally filching candy and soft drinks he wasn’t supposed to have, oh, no. He’d been on a first name basis with the police, in his worst brat-days; and when JR had said, Watch Jeremy , his imagination had instantly and nervously extended much further than JR might have expected, and to a level of responsibility JR might not have entirely conceived. Jeremy’s liberty wasn’t going to be nearly that exciting, because he wasn’t going to let his charges do any of those things. They gave him responsibility? He was going to come back to the ship in an aura of confidence and competence that would settle all question about whether Fletcher Neihart could be taken for a fool by three spacer kids. The converse was not to be contemplated.

Confined to Blue and Green ? That eliminated a whole array of things to get into. It was the high-rent area, the main banks, the big dockside stores, government offices, trade offices, restaurants and elite sleepovers.

It was where stationers who did venture into the docks did their venturing. It also was where the well-placed juvvie predators looked for high-credit targets, if this long-out-of-trade ship’s crew was in any wise naïve on that score. Finity juniors as well as the high officers had their pre-arranged sleepover accommodations in Blue , where, no, they wouldn’t get robbed in a high-priced sleepover, but short-changed, bill padded? They might as well have had signs on their heads saying, Rich Spacers, Cash Here. It was a tossup in his estimation whether Finity ’s reputation would scare off more of the rough kind of trouble than it attracted of the soft-fingered kind.

The junior-juniors weren’t going to handle their own money, not even the 20 c cash chits: he’d dole it out at need, and he was very confident the local finger artists couldn’t score on him. He almost hoped they did try, on certain others of the crew, notably Chad and Sue; he was confident at least the con artists would flock. Pick-pockets. Short-changers, even at the legitimate credit exchangers. Credit clerks would deal straight for stationers they knew were going to be there tomorrow, and who’d surely be back to complain if they got the wrong change. Spacers in civvies they might be just a little inclined to deal straight with… in case they were stationers after all. Spacers in dock flash and wearing their patches were a clear target for the exchange clerks; and God help spacers at any counter who might be just a little drunk, and whose board calls were imminent. Crooks of all sorts knew just as well as station administration did which ships were imminently outbound. When a ship was scheduled outbound, the predators clustered to work last moment mayhem.