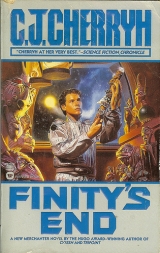

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

He wasn’t the only one looking for clean clothes. He stood in a line of six, all of whom introduced themselves with too damn much cheerfulness, a Margot with a -t, a Ray, a Nick, a Pauline, a Johnny T., and a John Madison who, he declared, wasn’t related to the captain. Directly.

He didn’t intend to remember them. He wasn’t remotely interested. He was polite, just polite. He smiled, he shook hands. Their chatter informed him you could pick up more than laundry at the half-door counter. You could buy personal items on your account, if you had an account, which as far as he knew he didn’t. As he approached the counter he could see, beyond the kid handing out the clothes, a lot of shelves with folded clothing sorted somehow. He saw mesh sacks of laundry left off and folded stacks of clean clothes picked up, and this supposedly was going to be his post. Big excitement.

“Fletcher,” he told the kid at the desk.

“Wayne,” the kid said. He looked no more than sixteen. “Glad you made it. So you take over here after next burn.”

“Seems as if.” He mustered no false cheerfulness. The other kid on duty, Chad, went and got the size he requested “ Finity patch is on,” Chad said of the ship’s blues he got. “Personal name patch, Sam’ll get to it as he can. He makes ’em. He’ll get it done for you before we go up.”

Up meant leave normal space. He knew that. He knew it was regularly about five days a ship took between leaving dock and exiting the system. “Yeah,” he said. “Thanks.”

A small plastic bag landed on top of the stack of folded blues, toiletries, and such. “There you go.”

“Thanks,” he said again, and carried his stack of slippery-bagged new clothes back the way he’d come, along a corridor that curved very visibly up.

That was it. He was assigned, checked in, uniformed, and set.

His gut was in a knot. He wanted to hit the first thing he came to. Nothing made sense. His stomach was sending him queasy signals that up and down were out of kilter, the horizon curves were steeper than he’d ever dealt with, and he was going to be a little crazy before he got off this ship, crazy enough he’d have memorized JR, James Robert, John, Johnny, Jake, Jim, and Jimmy, Jamie and all his damn relatives.

He opened the door to his room. This time there was a kid on the other bunk. A kid maybe twelve, dark-haired, dark-eyed, eyeing him with equal suspicion.

“Hi,” the kid said after a beat. “I’m Jeremy.”

“Yeah?” Defensively surly tone.

Defensively surly back. “I got lucky. We’re bunkmates.”

He must have frozen stock still a heartbeat. His heart speeded up. The rest of the room phased out.

“No, we’re not,” he said, and threw his new issue down on the other bunk.

“I live here,” was the indignant protest, in a pre-adolescent voice. “First.”

“No way in hell. This does it! This is the limit!”

“Well, I don’t want you here either!” the kid yelled back.

“Good,” he said. His voice inevitably went shaky if he didn’t let his temper blow and the struggle between trying to be fair with a hapless twelve-year-old and his desire to punch something had his upset gut in an uproar. It was the whole business, it was every lousy, stinking decision authorities had made about him all his life, and here it was, summed up, topped off and proposing he was rooming with a damned kid .

He dumped his new clothes on the bed. The door had closed. He went back and hit the door switch.

“They’re about to sound take-hold,” the kid’s voice pursued him as he left. “You can’t find anybody! You’ll break your neck!”

He didn’t damn care. He started down the hall, and heard someone shout at him and then footsteps coming.

“Don’t be stupid!” Jeremy said, and caught his sleeve. “They’re going to blow the warning. You haven’t got time to get anywhere else! Get back in quarters!”

The kid was in earnest. He had no doubt of that. He didn’t want to give up or give in, but the kid was worried, and maybe in danger, trying to stop him. He yielded to the tug on his arm and went back toward the room, wondering if he was being conned, or whether the kid knew what he was talking about. It was convincing enough.

And they no sooner were back in the room with the door shut than a warning sounded and Jeremy dived for his bunk.

“Belt in,” Jeremy said, and he followed Jeremy’s example, unclipped the safety belts and lay down, with the siren screaming warning at them all the while.

“Got time, there’s time,” Jeremy said, horizontal and fastening his belt. “ God , you don’t ever do that!”

He ignored the kid’s concerns and got the belt snugged down, telling himself if this turned out to be minor he was going to be madder than he was.

Then force started to build, not downward, but sideways, and the mattresses tilted sideways, so that he had a changing view of the inside bottom of the bunk beside him. His arms weighed three times normal, his whole body flattened and he could only see the bottom of Jeremy’s bunk, both rotated on the same axis, both swung perpendicular to the acceleration that just kept increasing.

He couldn’t fight it. He found himself shaking and was glad Jeremy couldn’t see it. He was scared. He could admit it now. He was up against something he couldn’t fight, caught up in a force that could break him if he ran out there in the hall and pitted himself against it. It went on, and on.

And on.

And on.

There wasn’t that much racket. Or vibration. Or anything. He shivered from fear and ran out of energy to shiver. He couldn’t see Jeremy. He didn’t know what Jeremy was doing. And finally he had to ask. “How long do we do this?”

“Three hours forty-six minutes.”

Shivering be damned. “You’re kidding!”

“That’s three hours fifteen to go,” Jeremy’s high voice said. “We like to clear Pell pretty quick. Lot of traffic. Aren’t you glad you didn’t go in the corridor?”

He couldn’t take being squashed in his bunk for three hours with nothing to do, nothing to view, nothing to think about but leaving Pell. Or the ship hitting something and everybody dying. “So what do you do when you’re stuck like this?”

“You can do tape. Or read. Or music. Want some music?”

“Yeah.”

Jeremy cut some on, from what source he wasn’t sure. It was loud, it was raucous, it was tolerable. At least he could sink his mind into it and lose himself in the driving rhythm. Inexorable. Like the ship. Like the whole situation.

It occurred to him finally to wonder where they were going. He’d never asked, and neither Quen nor his lawyers had told him. Just—from Quen—the news he’d be gone a year.

He asked when the music ran out. And the answer came from the unseen kid effectively double-bunked above his head:

“Tripoint to Mariner to Mariner-Voyager, Voyager, Voyager-Esperance, Esperance, and back again the way we came. There’s supposed to be real good stuff on Mariner. Fancier than Pell.”

Partly he felt sick at his stomach with the long, long recital of destinations. And he supposed he had to be glad their route was inside civilized space and not off to Earth or somewhere entirely off the map.

But he felt his heart race, and had to ask himself why he’d felt this little… lift of spirits when the kid said Mariner—which was supposed to be a sight to see. As if he was glad to be going to places he’d only heard about and had absolutely no interest in seeing.

But they were places Pell depended on. It wasn’t the Great Black Nothing anymore. He knew what places were out there. And Mariner was civilized.

“How you doing?” Jeremy asked in his prolonged silence,

“Fine.” The compulsory answer. The polite answer. But he got a feeling Jeremy at least considered him part of his legitimate business. And for a scruffy, skinny twelve-year-old, Jeremy was level-headed and sensible. There were probably worse people to get stuck with.

For a twelve-year-old. The obvious suddenly dawned on him. He knew that spacers didn’t age as fast as stationers. Sometimes they’d be ten, fifteen years off from what you thought—little that the difference from stationers’ ages had ever mattered to him, and little he’d dealt with spacers except his mother. But—on a kid—even a fraction of ten or fifteen years—was a major matter.

He was moderately, grudgingly curious. “Mind me asking?—How old are you?”

“Seventeen,” was Jeremy’s answer.

Good God , was his thought. Then he thought maybe the kid knew he was seventeen and was ragging him.

“Same age as you,” Jeremy’s voice said from the bunk above his head. “We’d have been agemates. Except your mama left.”

“You’re kidding. Right?”

“Matter of fact, no. I’m actually couple of months older than you. I was already born when your mama left to have you on Pell, and there was question about leaving me, but they didn’t. So you’re kind of like my brother.—We’d have been close together, anyway.”

He didn’t know what he felt, except upset. He’d been through the this is your brother routine four times with foster-families. He’d tried to pound one kid through the floor. But this was not only an honest-to-God relative, this was the kid he really would have grown up with, and been with, and done kid things with, if his mother hadn’t timed out on him and left him in one hell of a mess.

This was the path he really, truly hadn’t taken.

“I wish you’d been born aboard,” Jeremy said, “There weren’t any kids after us two, I guess you know. They couldn’t have ’em during the War. They will, now. But our years were already pretty thin. And then we lost a lot of people.”

Fletcher found a queasiness in his stomach that was partly anger, partly—he didn’t know. He could see what he might have grown into by now, a scrawny twelve-year-old body that was so strange he couldn’t imagine what Jeremy’s mind was like, seventeen and stuck at physical twelve.

It wasn’t natural.

It wasn’t natural, either, their being separated. He didn’t know. He didn’t know, from where he was lying, what kind of a life he’d missed. He only knew the life he was leaving, with all it did mean.

Besides, all the sibs people had tried to present him had ended up hating him, the way he hated them… except only Tony Wilson, who was in his thirties and his last foster sib. Tony’d been distant. Pleasant. The Wilsons had recognized he was a semi-adult, and just signed his paperwork, had him home from school dorms for special holidays, provided a legal fiction of a family for him to fill in school blanks with. Tony hadn’t ever remotely thought he was a rival. He supposed he’d liked Tony best of all the brothers he had, just for leaving him the hell alone most of the time and being pleasant on holidays.

Their not showing up when he was shipped out… that hurt. That fairly well hurt.

So who the hell was Jeremy Neihart and why should he care one more time?

“So,” Jeremy said in another long silence, “did you like it on the station?”

The question went right to the sore spot.“Yeah,” he said “Yeah, it was fine.”

“You have a lot of friends there?”

“Sure,” he said Everything was pleasant. Everything was fine. Never answer How are you? with anything but, and you never got further questions.

“So—what’d you do for entertainment?”

There hadn’t been any entertainment, hadn’t been any letup. Just study. Just—all that, to get where he’d been, where they ripped him out of all he’d accomplished

There wasn’t an, Oh, fine … for that one.

“I’ve got a lot of tapes,” Jeremy said when he didn’t answer. “We kind of trade ’em around. I got some from Sol. We can pick up some more at Mariner, trade off the skuz ones. I spent most of my money on tapes.”

“I don’t have any.” he answered sullenly. Which wasn’t the truth, but as far as what a twelve-year-old would appreciate, it was the truth.

“You can borrow mine,” Jeremy said.

“Thanks,”he said. He was too rattled and battered about any longer to provoke a deliberate fight with the kid. The kid .

His might-have-been brother. Cousin. Whatever they might have been to each other if not for the War and his addict mother.

On a practical level, Jeremy’s offer of tapes was something he knew he’d be glad of before they got to Mariner. He needed something to occupy his mind if they had to lay about for hours like this, or he’d be stark, staring crazy before they cleared the solar system. Tapes to listen to also meant he didn’t have to listen to Jeremy, or talk about might-have-beens, or deal with any of them. Plug in, tune out. He didn’t care what Jeremy’s taste in music turned out to be, it had to be better than dealing with where he was.

He was going to see the universe. Flat on his back and feeling increasingly scared, increasingly sick at his stomach.

He did know some things about ships. You couldn’t breathe the air on Pell Station without taking in something about ships and routes and cargo. Besides knowing vaguely how they’d travel out about five days and jump and travel and jump, he knew they’d load and unload cargo and the captains would play the market while the crew drank and screwed their way around the docks. Just one long party, which was why he had absolutely no idea who his father was. His mother had just screwed around on dockside because, sure, no spacer gave a damn who his father was. Mama was everything.

As he guessed Jeremy had a mother aboard, but he didn’t know why Jeremy wasn’t living with her, or for that matter, what he was supposed to be to his roommate’s mother. Everybody aboard was related. It was all the J’s. Jeremy, James, Jamie and Johnny, Jane, Janette, Judy, Jill and Janice. Who the hell cared?

What was it like for a mother to have a seventeen-year-old kid Jeremy’s size?

What was it to have your mind growing older and your body staying younger than it was?

Or was Jeremy more than twelve mentally? The voice didn’t sound like it, Jeremy wouldn’t have lived those seventeen years, he guessed, but he’d have watched seventeen years of events flow past him, in the news and on the ship. He’d—

Force just—quit. The bunks swung, and he grabbed the edges of the mattress with the feeling he was falling.

“ Takehold has ended ,” came from the speakers. “ Posted crew, second shift, you lucky people. All systems optimal .”

Jeremy was unbelting and sitting up. He figured he dared. His head was still feeling adrift in space.

“You play cards?” Jeremy asked.

“I can.” He didn’t want to. But he didn’t want to do anything else, either. “Can we go in the halls?”

“Corridors. Stations have halls. We have corridors. Just so you know. Vince’ll snigger, else. And we’re off-shift right now. Best stay in quarters if you don’t want to work. You wander around, some senior’ll put you to work. Poker?”

“How long do we have to stay lying around like this?”

“Oh,” Jeremy said, “about another couple of hours. Till we clear the active lanes.”

“I thought that was what we were doing.”

“Just gathering V . We’ll run awhile at this V . Then step up again. Four or five times before we get up to speed. We could do it all at once. But that’s real uncomfortable.”

“Deal,” he said glumly, and Jeremy bounced up, got into his bunk storage and rummaged out a plastic real deck.

Twelve-year-old body, he thought, watching the unconscious energy with which Jeremy moved. There were advantages to being twelve that even at seventeen you’d lost.

“Favor points or money?” Jeremy asked.

He knew about favor points. If you lost you ended up doing somebody’s work for him. He had no money. He didn’t know where he’d get any. He’d rather play for no points at all, because Jeremy handled those cards with dexterity a dockside dealer could envy.

“Points,” he said.

“You haven’t got an assignment yet.”

“Yes, I do. Laundry.”

“Oh, we all do that.” The cards cascaded between Jeremy’s hands. Fletcher bet he could do it under accel, too. “Future points. How’s that?”

“Fine,” he said.

He lost an hour to Jeremy. And was trying to win it back when a buzzer went off and scared him.

“Dinner,” Jeremy said, scrambling to his feet to get the door.

Somebody, another kid, whose name Fletcher didn’t bother to listen to, had a sack, and out of that sack the junior handed them two box suppers, little reusable kits containing—Fletcher’s hopes crashed as he looked—cold synth cheese sandwiches.

“Is this all we get?” Fletcher asked.

“Galley’s shut down,” Jeremy said “It’ll be up next watch.”

“How’s the food then?”

“Real good,” Jeremy said “We got real good cooks. Or we space ’em.”

Tired joke, but reassuring. Fletcher ate his synth cheese sandwich and drank the half-thawed fruit juice, trying to calm down. Very basic things had started mattering to him. He’d just about lost his composure, finding out food this evening was a sandwich. Shaky adjustment. Real shaky.

And here he was again. Been here before. Everything was new. Everything was the same as it had ever been. Worse than it had ever been. Spent half his seventeen years climbing out of the mess mama had left him in and here he was, back at the starting point.

The real one this time.

The lump in his throat went away. Sugar and protein helped. He figured he’d get good at poker on this cruise, if nothing else. Jeremy wasn’t so bad, for mental twelve—or a little more than that. Probably others weren’t.

When they ripped you out of one home and put you someplace else you tried never again to think of where you’d been, or miss anything about it. You just built as solid a wall as you could, So there was just a wall. Just a blank behind him. At least until the pain stopped.

Two hours into maindark and the Old Man finally asked. “How’s Fletcher?”

And JR, on the when-you’re-free summons to the Old Man’s topside office, gave the answer he’d predetermined to give: “Autopilot. He’s functioning. He’s not happy with this.”

“One wouldn’t think so,” James Robert said. James Robert wasn’t at his desk, but in the soft chair from which he did a great deal of his business. Cargo listings on the wall display screens had given way to system status reports and navigational data. “Has Jeremy complained?”

Jeremy had a beeper. With instructions to use it. “No, sir. He hasn’t.” Jeremy had seemed the best choice, over the junior-juniors there were. Vince was a heller from the cradle, always had been, and Linda, female and thirteenish, wasn’t an option.

A lot of empty cabins. There’d easily been a place to put Fletcher alone, as Jeremy had been alone, as Vince and Linda were alone. But he didn’t rate it safe for an uninformed, inexperienced passenger. Jeremy would warn him. Jeremy would take care of him.

“You had an encounter with him,” the Old Man said.

Not surprising that that news had made it topside. “I’m zeroing it out. Waiting to see. Can’t blame the guy for being on edge”

The Old Man just nodded, whether approving his attitude, or whether sunk in some other thought. The Old Man brought up other business, then, the general schedule, the maintenance windows, the expectations of other crew chiefs when the junior command would have to supply hands and bodies. The jump would come on main shift. Sometimes it did, sometimes it came during alterday. He’d expected alterday this time, but no, apparently not.

There wasn’t a mention of Fletcher’s life-and-death problems in facing jump for the first time, no special caution to be sure Fletcher got through it sane and in one piece, JR accepted it, then, as all on his watch, literally, as all things were that the sitting captains didn’t specifically cover in other assignments. The juniors were all mainday schedule. There weren’t enough of them for two commands, and they’d be working right up to the pre-jump. JR wondered whether that schedule were just possibly tailored around the new cousin.

And some things, like non-spacers, weren’t within his experience or his observation.

“On the Fletcher question,” JR said, in the Old Man’s silence, “does he get tape, or not, during jump? Should I take him into my quarters and see him through it? ”

All of them had experienced hyperspace in the womb. Experienced it until their lives were strung out in it.

Fletcher was definitely a question mark.

“Leave tape study off,” the Old Man said “I’d say, not this trip, for him or for Jeremy. I’d say—you stay off tape, too. I want you able to respond.”

“Yessir,” he said

“Where he rides it out,” the Old Man said, “is your discretion. You’re closer to the situation than I am. Tell him—”

Rare that the Old Man failed to have exactly what he wanted to say, exactly as he wanted it

But the last few days of “Fletcher’s lost” and “Fletcher’s found” and “Fletcher will be another day late” had worn on everyone, and based on past events, he began to suspect the Old Man knew the uneasy feeling in the junior crew, and saw deeper into his personal misgivings than he liked.

The Old Man’s chain of consequences, on the other hand, went right back into the decision to join Norway and leave Francesca.

The hero, the old warrior, said they had a peace to fight now, and they’d taken on non-military cargo as well as an outsider, both for the first time in nearly two decades.

But Mallory’s War wasn’t over, Mallory and the Old Man had had words of some kind when last they’d met, out in the remote fringes of Earth’s space. And whatever they’d said, it was solemn and sobering in its effect on the Old Man, who’d come back solemn and sad, and not one word had filtered down to his level.

Tell him—the Old Man had begun, and found no words for what to tell Francesca’s heir, either.

So there was no information for him, just an urging to make the situation work… somehow… within the junior crew, where the Old Man didn’t, on long-standing principle, interfere. It was the future relationships of the members of that crew to each other that they were hammering out in their conduct of a set of duties and responsibilities all their own, the way Finity crew had done for more than a century. In a certain measure the Old Man couldn’t reach into that arrangement to settle and protect one special case without skewing every relationship, every reliance, every concept of personal honor and chain of command the junior crew maintained

Fletcher had to make a Fletcher-shaped place in the crew. There couldn’t be less. Or more. And it wasn’t the Old Man’s job to do it. He got that from the silence, when he knew that the Old Man had thought a very great deal about Fletcher before he came aboard.

“I’ll take care of him,” JR said, and received back only a sidelong look from the Old Man. When JR looked back in leaving, the Old Man was busy at his work again, clearly with no intention of asking or saying further in the matter.

Chapter 8

Morning mess hall was another collection of cousins, mostly seniors. Fifty people ate at a set time, on schedule—be hungry or skip it entirely, unless you had an excuse or a favor-point with the cook, so Jeremy said.

Fletcher ate at the same table with Jeremy and two other only moderately pubescent juniors, Vincent and Linda, both doubtless older in station years than they seemed, but mentally like the age they looked, they mostly jabbered about games or what they’d done on Pell docks, their speech larded with wild, decadent , and fancy , juvvie-buzz that seemed current among their small set. Mostly they ignored him, beyond the first exchange of names, turned shoulders to him without seeming to notice it in the heat of their conversational passion, and Jeremy’s eyes lit with the game-jabber, too.

Being ignored didn’t matter to Fletcher. He’d lain awake and tossed and turned in his bunk. Jeremy had lent him music tapes and those had gotten him through the dark hours.

But today he had to work with these kids who admittedly knew everything he didn’t; and he went with them when they’d had their breakfast—a decent breakfast, if he’d had the appetite, which he didn’t.

They all went, still jabbering about dinosaurs and hell levels, down to A14, and in the next few hours he learned all about laundry, how to sort, fold, stack, and keep a cheerful face right along with the two other juniors in the mess pool with him and Jeremy.

They’d drawn Laundry as their work for this five-day stint… but not every day. You didn’t get stuck on one kind of job as a junior. That was a relief to learn.

The junior-juniors, the ship’s youngest, the seventeen– and eighteen-year-olds among whom he was unwillingly rated, drew such jobs relatively often. But so did the mid-level techs, from time to time. Juniors, so Jeremy said, rotated through Laundry to Minor Maintenance, to Scrub, to Galley, but there were jobs all over the ship that were rotating jobs, or part-time jobs, or jobs people did only on call.

Junior-juniors inevitably got the worst assignments, Fletcher keenly suspected. Laundry was everybody’s laundry; laundry for several hundred people who’d been out on liberty for two weeks was a lot of laundry, sonic and chemical cleaning for some tissue-fabrics, water-cleaning for the rough stuff, dry, fold, sort, and stack by rank.

It filled the time that otherwise would have required too much thinking, and it was a job where you did meet just about everybody, as people came to the counter for pickup of what they’d sent in at undock and to pick up small store items like soap refills for their showers, and sewing kits, and other odd notions.

Fletcher didn’t remember all the names by half—except Parton, who was blind, and who had one mechanical eye for ordinary things, Jeremy said, and the other one was a computer screen for cargo data or anything else Parton elected to receive. He didn’t think he’d forget Parton, who asked him to stand still a moment until his mechanical vision had registered a template of his face. He’d never met a blind person. But Jeremy said Parton’s left eye was sharp all the way into situations where the rest of them couldn’t see, and Parton didn’t always know whether there was light or not. His mechanical eye could spot you just the same.

Laundry pickup was a place to hear gossip—all the gossip in the ship, he supposed, if you kept your ears open. He picked up a certain amount of information on certain individuals even with no idea who he was hearing about, and he heard how various establishments on Pell didn’t meet the approval of the senior captain.

Vincent and Linda talked about various places you’d go in civvies , and restaurants you’d wear a patch to , meaning the ship’s patch, he guessed. Someone dropped by the counter and gave him his own, ten black circular ship’s patches, and small patches that said Finity’s End and Fletcher Neihart . It was, he supposed, belonging . He wasn’t sure how he felt about them.

Jeremy handed him a sewing kit from off the shelf of supplies. “You stitch ’em on,” Jeremy said. “The shiny-thread ones are for dress outfits, the plain-thread are for work gear. If they start looking tatty you get new ones or the watch officer has a fit. I’ll show you how, next watch.”

Labels got your laundry back to you, that was one use of them he saw. You also had a serial number. He was F48, right next to his name. He saw that in a roll of tags that was also in the packet the man had given him. Those were just for the laundry. It was a lot of sewing on tags.

Even in the underwear and the socks.

Labeled. Everything. Head to toe.

He didn’t say anything. He didn’t like it. On Base he’d had to do his own laundry. Everybody did. You got your clothes back because you sensibly never dumped them in bins with everybody else’s. He’d never learned to sew anything in his life, but he figured he’d learn if he wanted his socks and underwear back.

Labeling right down to his socks as Finity crew, though, he’d have skipped that if he could. But counting they’d lose your underwear if you didn’t, it seemed a futile point on which to carry on a campaign of independence, or make what was a tolerable situation today harder than it was. Nobody had done anything unpleasant—or been too intrusively glad to see him. Vincent tried to engage him about where he’d been, holding up the ship and making them late on their schedule, but Jeremy told Vince to stop and let him alone and Vince, who came only up to mid-chest on him, took stock of him in a long look and shut up about it.

Jeremy wanted to talk about Downbelow when they got back to quarters after mess, and that was harder. They sat there stitching his labels into his socks, and Jeremy wanted to know what Downbelow looked like.

“Real pretty,” he said.

“There’s trees on Pell,” Jeremy said

“Yeah. The garden. The ones on Downbelow are prettier.” He jabbed his finger with the needle, painfully so. Sucked on it. He and Jeremy sat on their respective bunks, with a stack of his entire new wardrobe and all the clothes he’d brought with him plus a pile of the clothes he’d gotten dirty so far, and he wasn’t sorry to have the help doing it.

He daydreamed for an instant about puffer-ball gold and pollen skeining down Old River, beneath branches heavy with spring leaves. Rain on the water.

Jeremy chattered about what he’d seen in Pell’s garden. And segued nonstop to what he wanted to do after they got the patches stitched on. Jeremy wanted him to go to rec with him tonight: there was a rec hall, with games and a canteen, Jeremy said.

“I don’t want to.”

“Oh, come on. What are you going to do, else?”

It was a point. He’d be alone in this closet of a room. He was tired, but he’d get to thinking about things he didn’t want to think about.

He went. It was the same huge compartment they’d all been in during undock, only now there were no railings. There were game machines. A vid area. Tables and chairs, senior as well as junior crew playing cards, playing games, watching vids. He suffered a moment of dislocation, and almost balked at the transformation alone.

But the entertainments offered were very much like at the Base. Familiar situation. You mixed with senior staff and techs and all. They just generally didn’t talk with junior staff.

“What do you play?” Jeremy asked him.

Dangerous question. He’d already lost ten hours to Jeremy at cards; but when he glumly decided on vids, and looked through the available cards in the bin to the side of the machines, he found an Attack game he hadn’t seen since he was a small kid. The card itself when he pulled it out was old, showing a lot of use; but he remembered that game with real pleasure, and recalled he’d been pretty good at it—for a seven-year-old. He might have a chance at this one.