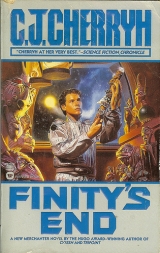

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

Meanwhile the Belize senior captain had had a very cordial session with the Old Man of Finity’s End , and word was that bottles from Finity ’s cargo, duly tariffed and taxed, were making their way to various ships. If spies were taking notes of the number of captains who got together in a shifting combination of venues, they must have a full-time occupation; what worried him, and what he was sure would worry the Old Man, was the likelihood that Belize’s internal security was as lax as its concept of restricted residency.

If the Belize captain had talked too much to his own crew, some of their business could have gotten into that sleepover room last night and right into the ears of curious Champlainers.

Who now were outbound.

It had to be a successful stay on dockside, Fletcher said to himself: Jeremy had a stomachache and all of them had run out of money. Here they were, standing in line for customs three days earlier than their scheduled board call, a moving line. Customs was just waving them through.

Their loading must have gone faster than estimated. And Fletcher was relatively proud of himself. He’d had the pocket-com switch in the right position; he’d gotten the call, figured out the complexities of the pocket-com to be able to key in an acknowledgement that they were coming, and gotten the juniors to the dock with no more delay than a modest and reasonable request from Jeremy to make a last-minute dive into a shop near the Pioneer to get a music tape he’d been eyeing. And some candy.

So Jeremy wasn’t so sick as to forswear future sweets.

And instead of the slow-moving clearance of passports in their exit, they advanced through customs at a walk, flashed the passport through the reader on the counter, only observed by a single customs agent, tossed their duffles uninspected onto the moving cargo belt for loading, and walked up the ramp to the access tube, where for brief periods the airlock stood open at both ends to let groups of them walk through.

“They are in a hurry,” Linda said when she saw that.

“New Old Rules,” Vince said. “Maybe they’re going to do that after this. No more lines.”

“We’ve got a security alert,” a senior cousin behind them said, breath frosting in the chill of the yellow, ribbed access.

“About what?” Jeremy asked.

“Just a ship we don’t like. But we’re not going out alone.” The cousin ruffled Jeremy’s hair and Jeremy did the time immemorial wince and flinch. “No need to worry.”

“So who are they?” Fletcher asked, not sure what security alert entailed, whether it was a trade rivalry or a question of guns and something far more serious.

“What we’ve got,” the cousin behind that cousin said—one was Linny and the other was Charlie T.—“what we’ve got is a rimrunner for the other side. But we’ve also got an escort. Union ship Boreale is going to go our route with us.”

A Union ship?

“Do we trust them?” Fletcher asked.

“Sometimes,” Charlie T. said. And about that time the airlock opened up and started letting them through, a fast bunch-up and a press to get on through and out of the bitter cold. They went through in a puff of fog that condensed around them. They’d put down a metal grid for traction as they entered the corridor, and it was frosted and puddled from previous entries.

Mini-weather, Fletcher thought, his head spinning with the possibilities of Union escorts, an emergency boarding. But the cousins around him remained cheerful, talking most about Mariner restaurants and what they’d found in the way of bargains in the shops. A cousin had a truly outlandish shirt on under the silvers. And it was a strong contrast to his last boarding in that he knew exactly where he was going, he knew they’d been posted to galley for their undock duty—laundry would have been entirely unfair to draw this soon—and he was actually looking toward his cabin, his bunk, his mattress and the comforts of his own belongings after the haste and nonstop party of dockside, which he’d thought would be hard to leave, when he’d gone out. He’d bought some books he was anxious to read, he’d bought games that promised hours of unraveling, and even a block of modeling medium—a long time since he’d had the chance to do any model-making; he’d used to be good at it.

He took the sharp turn into the undock-fitted rec hall, herded his three charges in to the rows of rails and standing cousins, but he had second thoughts about Jeremy.

“Are you all right?” he asked, delaying at the start of the row and holding up traffic. “You want to talk to Charlie, maybe get something for your stomach? Maybe go to the sit-down takehold?”

“No,” Jeremy said, and flashed a valiant grin. “I’m fine.”

“If he gets sick everybody’ll kill him,” Linda said helpfully as Jeremy went on into the row.

“Just if you don’t feel right, tell me.”

“No, I’m fine,” Jeremy said, and they all packed themselves into the eighth row among an arriving stream of cousins.

Everybody had called to confirm they were on their way, customs was expediting, and the ship was go when ready, that was the buzz floating in the assembly. It was the kind of thing Finity had used to do, or so the talk around him indicated; and at the rate the prelaunch area was filling up they were going to be clearing dock… the estimate was… maybe in twenty minutes.

Boreale , their Union escort, was on the same shortened schedule.

“What did this ship do?” Fletcher asked of Charles T. “Why are we suspicious?”

“It left dock early. Going our way.”

“Is it going to shoot at us, or what?”

“It could have that intention,” Charles T. said. “That’s why Boreale is going with us.”

“What they think,” said another cousin, turning around from the row in front, “is that Champlain —that’s the ship in question—is going to report somewhere ahead of us. It’s an outside possibility it might want to take us on. But not two of us. Boreale’s a merchanter only in its spare time, and it’d like that ship to make a move. If we can build a case that ship’s Mazianni, there are alternatives we can take at Voyager.”

“They’ve had a watch on our hull the whole time we’re here,”a third cousin said. “So we’re clean.”

Watching for what ? Fletcher wondered uneasily, but his mind leapt to uneasy conclusions.

“Don’t suppose they’ve watched theirs ?” Charles T. said with a wicked grin.

“Tempting,” Parton said.

The juniors were all ears. Even Jeremy.

Another flood of cousins poured in. “ Ten minutes ,” the intercom said in the same moment. “ We’ve got a potential bandit, gentle cousins, but our intrepid allies out of Union space are going to pace us in fond hopes of getting the goods on the rascals. We’ll make specific safety announcements before jump, but we’re clearing dock in plenty of time for Champlain to figure the odds, which we think will discourage a wise captain from lingering to meet us in the jump-point. We will be doing an unusual system entry just in case our piratical friends have strewn our path with any hindrances, and we will post the technicals on the maneuver for those of you who have a curiosity about the matter. Welcome aboard, welcome aboard, welcome aboard. We hope your hangovers are less than you deserve. Fare well to Belize and Mariner, and fond hopes for Esperance. Voyager will be a working port, we regret to say, with restricted liberty and fast passage .”

There were groans.

“We’re going to work ?” Vince cried indignantly.

“Sounds like an interesting stop,” a cousin said. “Are we hauling this trip, or how much did we load?”

Time spun down. A last few cousins ran in, JR and Bucklin among them. Chad, Connor and Sue followed, and then the rest of the juniors… probably on duty, Fletcher said to himself. The icy mess in the corridor was a likely junior job, of the sort that wouldn’t wait for undock, during which icemelt could run and metal grids could slide.

Odd thought… how much he’d gotten to figure out without half thinking about it. His ship. His junior-juniors. His roommate. He’d been out on liberty, he’d come back in charge of three kids who’d come around somehow to admitting that seventeen waking years beat twelve and thirteen in a lot of respects: he’d been in his element, and the one he was coming back to wasn’t foreign, either, now.

He knew these people. He knew the sounds he’d heard before, and wished there were a way to ask, when the undocking started, exactly what sound was what. He’d stood and watched ships undock, from outside, and the lights would be flashing and the hatches would seal, and the access tube would retract. Then the lines would uncouple, the gantry arm would pull back.

Then the grapples. That was the loud one. The jolt. Somebody started a loud and rowdy song, that subbed in the word Belize , and he found himself with a grin on his face as Finity’s End came free and powered back from dock.

One song topped another one, and they ran out of the rowdy ones and into the sentimental, good-bye to the port, good-bye to lost loves…

He had an urge to chime in, but he was too conscious of the juniors beside him and he couldn’t sing worth a damn. He could listen. He could feel a little shiver of gooseflesh on his arms, a little shortness of breath when the song wound on to foreign ports and lost friends.

They knew. He wasn’t different. He knew he was slipping under a spell, and that Downbelow was getting farther and farther away. He’d heard about meetings, in the chaff of conversation before undock. He’d heard about the captains getting together and talking about peace.

And now Union was escorting an Alliance ship?

He’d thought he understood the universe, or all of it he needed to know. And things weren’t what he thought.

“ Clear to move ,” the intercom said. “ Twenty minutes to get your baggage and ten to take hold, cousins. Move, move, move .”

The front row filed out to the corridor and the next row was hot on their heels, everybody moving with dispatch when it was their turn.

Cargo spat out baggage at high speed and fair efficiency. He’d bought a silly cartoon trinket to hang from the tag, a distinction easier to spot, he’d learned, than the stenciled name; and Jeremy had urged him to buy it. Other people had colored cords, plastic planets, tassels… Jeremy’s was a metal enameled tag that said Mars, and a cartoon character of no higher taste than his. Jeremy’s duffle was already in the stack, but his wasn’t.

Jeremy carted his off. Fletcher saw his own come down the chute and grabbed it, double-checking the tag to be sure.

“Fletcher,” JR said, turning up beside him, and instinct had him braced for unpleasantness as he straightened and looked JR in the eyes.

“Good job,” JR said. “I can’t say all of it, even yet, but we’ve had a situation working at this port… same that put that ship out ahead of us, and it wasn’t a place to let our junior-juniors in on the matter, or to let them wander the dockside on their own. Toby and Wayne kind of kept an eye in your direction, you may have observed at first, but you didn’t need help, so they just pretty well left things to you and after that we got swept into running security for the captains’ business and didn’t check back, in the absence of distress signals. But we didn’t feel we had to. So we do appreciate it, and I’m speaking for all of us.”

He wasn’t used to well-dones. He didn’t have a repertoire of suitable polite remarks. His face went hot and he hoped it didn’t show.

“Thanks,” he said. If he was one of the Willetts or the Velasquezes he’d have learned how to shed compliments like water. But he wasn’t. And stood there holding a duffle with a plastic, large-eyed cartoon wolf for an identifying tag. The one JR had against his leg sported a classy Sol One enamelled tag, which he’d undoubtedly bought above Earth itself.

“We got out all right,” JR said, “and regarding what the captain was talking about to you before we made dock… and the reason we’re running with an escort right now… I’m warning you in advance we’re not going to get much of a liberty at Voyager. We can’t guarantee their cargo handling and we’re going to have to search every can. This is not going to be a fun operation. But we have to do it. We have to look as if we trust Voyager without actually trusting Voyager. Again, that’s for you to know. The junior-juniors aren’t to know the details.”

“And I am ?” He couldn’t help it. He didn’t see himself in the line of confidences.

JR looked him straight in the face. “You need to know. You’re watching the potential hostages. And you need to know.”

“You don’t know me . Where do you think I’m so damn trustworthy?”

JR outright grinned. “Because you’d warn me like that.”

He’d never been outflanked like that. He shut his mouth. Had to be amused.

“ Takehold in ten minutes ,” the intercom advised them, and JR picked up his baggage.

“Got to walk my quarter,” JR said. And set off. “Don’t forget your drug pickup!” JR called back.

He would have forgotten. Remembered it by tomorrow, but he would have forgotten. Fletcher took his duffle, slung it over his shoulder and walked in JR’s direction far enough to reach the medical station and the drug packets set out in bundles.

Take 6 , the direction said, a note taped to the side of the bin on the counter, and the bin was three-quarters empty. He came up as JR was initialing the list as having picked up his. JR took his six, and Fletcher signed in after and filled his side pocket with the requisite small packets, asking himself, as his source of information walked away, what circumstance could demand six doses.

Precaution on the precaution, he said to himself, and, drugs safely in pocket, and feeling proof against the unknown hazards of yet another voyage, he toted his duffle back the other direction, past the laundry and past a sign that instructed crew not to leave laundry bundles if the chute was full.

Piled up on the floor inside, he well guessed, glad it wasn’t his job this turn. Galley was a far better duty.

He walked on to A26, to his cabin, anticipating familiar surroundings—and almost reached to his pocket for a key as he reached the door, after a week in the Pioneer. He reached instead to open the door.

Beds were stripped, sheets strewn underfoot. Drawers and lockers were open, clothes thrown about. Jeremy, inside with his arms full of rumpled clothes, stared at him with outright fear.

“What in hell is this?” he asked.

“I’m picking it up,” Jeremy said.

“I know you’re picking it up. Who did it? Is this some damn joke?”

“It’s your first liberty.”

“And they do this ?”

“I’m picking it up!”

“The hell!” His mind flashed to the bar, to Chad sitting there with all the others. Butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths. He stood there in the middle of the wreckage of a cabin they’d left in good order, feeling a sickly familiarity in the scenario. No bloody wonder they’d been smiling at him.

He saw articles of underwear strewn clear to the bathroom, his study tapes and what had been clean, folded clothes lying on a bare mattress. The drawer where he kept his valuables was partially open, the tapes were out—the drawer showed empty to the bottom, the drawer where he’d had Satin’s stick; and he bumped Jeremy aside, dropping to his knees to feel to the back of the storage.

Nothing. He got up and looked around him, rescued his tapes and the rumpled clothes to the drawer and lifted the mattress, flinging it back against the lockers to look under it.

“I’ll check the shower,” Jeremy said, and went and looked and came back with more of his clothes.

No stick.

“Shit!” Fletcher said through his teeth. He looked in lockers, he swept up clothes, he rummaged Jeremy’s drawers.

Nothing. He slammed his hand against the wall, hit the mattress in a fit of temper and slammed a locker so hard the door banged back and forth. A plastic cup fell out and he caught it and slammed it into the wall. It narrowly missed Jeremy, who stood, white-faced, wedged into a corner.

Fletcher stood there panting, out of things to throw, out of coherent thought until Jeremy scuttled out of his corner and grabbed up clothes.

He grabbed the clothes from Jeremy, grabbed Jeremy one-handed and held him against the wall. “Who did this?”

“I don’t know!” Jeremy said. “I don’t know, they do this sometimes, they did it to me. First time you go on liberty—”

“ Fletcher and Jeremy ,” the intercom said “ Report status .”

“We hit the wall,” Jeremy reminded him breathlessly. “They want to know if we’re all right. Next cabin reported a noise.”

“You talk to them.”He wasn’t in a mood to communicate.

He let Jeremy go and Jeremy ran and, fast talking, assured whoever it was they were all right, everything was fine.

It took some argument. “ One minute to take hold ,” another voice on the intercom said then. “ Find your places .”

Jeremy started grabbing up stuff.

“Just let it go!” Fletcher said

“We have to get the hard stuff!” Jeremy cried, and grabbed up the cup he’d thrown, the toiletry kit, the kind of things that would fly about in a disaster. Fletcher snatched them from him, shoved them into the nearest locker and slammed the door.

Then he flung himself down on the sheetless bed and grabbed the belts. Jeremy did the same on his side of the room.

The intercom started the countdown. He lay there staring at the ceiling, telling himself calm down, but he wasn’t interested in listening.

They’d gotten him, all right. Good and proper. They’d probably been sniggering after he left the bar.

Maybe not. Maybe Chad had. Chad and Connor and Sue, he’d damn well bet. They’d cleared the cabins and the senior- juniors were still running around the ship, well able to get into any cabin they liked, with no locks on any door.

“I’m real sorry!” Jeremy said as the burn started.

He didn’t answer. The bunks swiveled so that he was looking at the bottomside of Jeremy’s, and so that he had a good view of the empty drawers and the underside of the bunk carriage, and Satin’s stick wasn’t there, either. He even undid the safety belts and stuck his head over one side of the bunk and the other, trying to see the underside. He held on until acceleration sent the blood to his head and, no, it wasn’t stuck to the bottom of the bunk carriage, wasn’t stuck to the head of the bunk—wasn’t stuck to the foot, which cost him a struggle to search. He lay back, panting, and then snapped at Jeremy:

“Look down to your right, see whether it’s down in the framework.”

A moment. “It’s not there. Fletcher, I’m sorry…”

He didn’t answer. He didn’t feel like talking. Jeremy tried to engage him about it, and when he didn’t answer that, tried to talk about Mariner, but he wasn’t interested in that, either.

“I’m kind of sick,” Jeremy said, last ploy.

“That’s too bad,” he said. “Next time don’t stuff yourself.”

There was quiet from the upper bunk, then.

Chad. Or Vince. And he’d lean the odds to it being Chad.

He replayed everything JR had said, every expression, every nuance of body language, and about JR he wasn’t sure. He didn’t think so. He didn’t read JR as somebody who’d enjoy that kind of game, standing and talking to him about how well he’d done, and all the while knowing what he was walking into.

He didn’t think JR would do it, but he wanted to talk to JR face to face when he told him. He wanted to see the reactions, read the eyes, and see if he could spot a liar: he hadn’t been damn good at it so far in his life.

It hurt. Bottom line, it hurt, and until he talked to the senior-junior in charge, he didn’t know where he stood or what the game was.

Chapter 17

Boreale was also out of dock, likewise running light, about fifteen minutes behind them. That made for, in JR’s estimation, a far better feeling than it would have been if they’d had to chase Champlain into jump alone.

It also made their situation better, courtesy of the station administration, for Finity to have had access to Champlain’s entry data, data on that ship’s behavior and handling characteristics gathered before they’d known they were under close observation. They had that information to weigh against its exit behavior and its acceleration away from Mariner, when Champlain knew they were carefully observed.

That let them and Boreale both form at least some good guesses both about Champlain’s capabilities and the content of its holds. And at his jump seat post on the bridge, JR ran his own calculations on that past-behavior record, keeping their realtime position and Boreal’s as a display on the corner of the screen, and calling on a large library of such records.

Finity’s End , in its military capacity, stored hundreds of such profiles of other ships of shady character, files that ordinary traders couldn’t access and which (he knew the Old Man’s sense of honor) they would never use in competing against other ships in trade. The data included observations of acceleration, estimates of engine output, maneuvering capacity, loading and trade information not alone from Mariner, but black-boxed information that came in from every port in the shared system—and they had that on Champlain .

He was very glad to have confirmation of what common sense told him Champlain had done—which was exactly what they had done. She’d offloaded, hadn’t taken in much, had most of her hauling mass invested in fuel: she’d taken on enough to replace what she’d spent getting to Mariner, but no one inspected the total load. She was possibly even able to go past Voyager without refueling.

Finity had to fuel at Voyager. If they delayed to offload cargo and take on more fuel, they’d lose their tag on Champlain even if Champlain did put into that port. But Finity ’s unladed mass relative to their over-sized engines meant they’d still handle like an empty can compared to Champlain , unless Champlain’s hold structure camouflaged more engine strength than the estimate persistently turning up in the figures he was running.

Boreale was likewise high in engine capacity, and she was also far more maneuverable than Champlain , if the figures they had on their ally of convenience were right. They’d been hearing about these new Union warrior-merchanters. Now they had their chance to observe one in action, and Boreale couldn’t help but be aware of their interest and who they reported to…

The com light blinked on his screen. Somebody wanted him. He reached idly and thumbed a go-ahead for his earpiece.

Fletcher. A restrainedly upset Fletcher, who wanted to talk.

“I’m on duty,” he said to Fletcher. “I’m on the bridge.”

“That’s all right,” Fletcher said. “I’ll wait as long as I have to.”

The quiet anger in the tone, considering Fletcher’s nature, said to him that it might be a good idea to see about it now.

“I’ll come down,” he told Fletcher. “Where are you?”

“My quarters.”

“I’ll be there in a moment.” He signaled temporarily off duty , and stored and disconnected on his way out of the seat

Fletcher sat on the bed, in the center of the debris. And waited.

Jeremy had left to report to Jeff, in the galley, for both of them.

Fletcher sat, imagining the time it took to leave the bridge, walk to the lift and take it down to A deck…

To walk the corridor.

He waited. And waited, telling himself sometimes the lift took a moment. People might stop JR on the way…

The light by the door flashed, signaling presence outside.

Fletcher got up quietly and opened the door.

JR’s face said volumes, in the fast, startled pass of the eyes about the room, the evident dismay.

JR hadn’t expected what he saw. And on that sole evidence Fletcher held on to his temper, controlling the anger that had him wound tight.

“Jeremy went on to duty,” he said to JR in exaggerated, careful calm. “This is what we came back to.”

“This…” JR said, and seemed to lose the word.

“This is a joke, right?”

“Not a funny one. Clearly.”

He hadn’t been able to predict what he himself would do. Or say. Or want. He was angry. He wasn’t, he decided now, angry at JR. And that was not at all what he’d have predicted.

“I’d discouraged this,” JR said. “It’s supposed to be a joke, yes. Your first liberty. But it shouldn’t have happened. Was anything damaged?”

“Something was stolen.”

JR had been looking at the damage. His eyes tracked instantly back again, clearly not comfortable with that charged word. He’d deny it, Fletcher thought. He’d quibble. Protect his own. Of course.

“ What was?” JR asked

He measured with his hands. “A hisa artifact. A spirit stick. Wood. Carved, tied up with cords and feathers.”

“I’ve seen them. In museums. They’re sacred objects.”

“I had title to it.”

“I take your word on it. You had it in your cabin. Where?”

“In the drawer.” He indicated the drawer in question with a backward kick of his foot “At the back of the drawer. Under clothes. I’ve been over every inch of the room. Including under the bunk frames as they’d tilt underway. It’s not here. I don’t give a damn about them tearing up the room. I don’t like it, but that’s not the issue. The stick is. The stick is mine , it was a gift, and it’s not something you play games with.”

“I’m well aware.” JR looked around him and frowned, thinking, Fletcher surmised, where it might be, or very well knowing the chief suspects on his own list

“I don’t even know it’s on this ship,” Fletcher said “I don’t know why they thought it was funny to take it. I don’t even want to imagine. I can point out that the market value is considerable, for someone who might be interested in that sort of thing. And that we’ve been in port.”

He’d hit home with that one. JR frowned darker still.

“No one on this ship would do that ,” JR said.

“You tell me what they would and won’t do. Let me tell you. Somebody sitting at your table, in the bar the other evening, looked me straight in the eye knowing damned well what he’d done. Or she’d done. They kept a real straight face about it. Probably they had a good laugh later. I’m serving notice. I can’t work with people like that. I want off this ship. I gave you my best shot and my honest effort. And this is what I get back from my cousins . Thanks. If you want to do me a personal favor, sell me back to Pell and let me get back to my life. If you want to do me a bigger favor, get me passage back from Voyager. But don’t ask me to turn a hand to help anybody on this ship. I want my own cabin, the same as everyone else. I don’t want to be with Jeremy. I don’t want to be with anybody. I want my privacy, I want my stuff left alone, I don’t want any more of your jokes, and I don’t want any more crap about belonging here. I don’t . I think that point’s been made.”

JR didn’t come back with an argument. JR just stood there a moment as if he didn’t know what to say. Then:

“Have you discussed this with Jeremy?”

“ No , I haven’t discussed it with Jeremy. I have nothing against Jeremy. I just want the lot of you off my back!”

“I can understand your feelings. If you want separate quarters, I can understand that, too. But Jeremy’s going to be affected. He’s taken to you in a very strong way. I’d ask you give that fact whatever thought you think you ought to give. I’ll talk to the captains; I’ll explain as much as I can find out. I’ll find the stick, among other things. And if you want someone to clean this mess up, I’ll assign crew to do that. If you’d rather I not…”

“No.” Short and sharp. “I’ve had quite enough people into my stuff. Thanks.” He was mad as hell, charged with the urge to bash someone across the room, but he couldn’t fault JR on any point of the encounter. And he didn’t hate Jeremy, who’d left with no notion of his walking out. “I’ll think about the room change. But not about quitting. It’s not going to work. You’ve screwed up where I was. I don’t ask you to fix it. You can’t. But you can put me back at Pell.”

“There’s no way to get you passage back right now. It wouldn’t be safe. You have to make the circuit with us.”

He wasn’t surprised. He gave a disgusted wave of his hand and turned to look at the wall, a better view than JR’s possibilities.

“I’m not exaggerating,” JR said. “We have enemies. One of them is out in front of this ship likely armed with missiles.”

“Fine. They’re your problem.”

“Fletcher.”

Now came the lecture. He didn’t look around.

“Give me the chance,” JR said, “to try to patch this up. Someone was a fool.”

“Sorry doesn’t patch it.” He did turn, and stared JR in the face. “You know how it reads to me? That my having a thing like that on this ship was a big joke to somebody on this ship. That the hisa are. That everything the hisa hold sacred and serious is. So you go fight your war and make your big money and all those things that matter to you and leave me to mine!

You know that hisa don’t steal things? That they have a hard time with lying? That war doesn’t make sense to them? And that they know the difference between a joke and persecution? I’m sure they’d bore you to hell.”

“Possibly you’re justified,” JR said. “Possibly not. I have to hear the other side of this. Which I can’t do until I find out what happened. Let me be honest, at least, with our situation—which is that we’ve got a hostile ship running ahead of us, and there may be duty calls that I have to answer with no time for other concerns. On time I do have control of, I’m going to find the stick, I’m going to get answers on why this happened, and I’m going to get your answers. I put those answers on a priority just behind that ship out there, which is going to be with us at least all the way to Voyager. I don’t consider the hisa a joke and I don’t consider anything that’s happened a joke. This ship can’t afford bad judgment. You’ve just presented me something I don’t like to think exists in people I’ve known all my life, and quite honestly I’m upset as hell about it. That’s all I can say to you. I will follow up on it.”

“Yessir,” he found himself saying, not even thinking about it, as JR turned to leave. And then thinking… so far as he had clear thoughts… that JR was being completely fair in the matter, contrary to expectations, that he had just said things that attacked JR’s personal integrity, and that he had the split second till JR closed the door to say something to acknowledge that from his side.