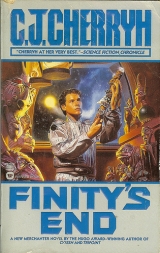

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“I got my tooth chipped the first time station-boy threw a punch out of nowhere!”

“Chad.”

“Yessir,” Chad said.

“And don’t call him that. No words, Chad, same as no fighting.”

“Yessir,” Chad said the second time.

“I take your word on it,” he said, wishing it weren’t Chad’s word that was utterly at issue.

And that Chad wasn’t the only potential explosive in their midst. There was Connor. There was Sue. There was Nike.

Vince seemed to have fallen in on the side of the offended, not the offenders. Vince was, at least, off his mind.

No sign of the stick, not the first twenty-four hours, not the second, and the junior-juniors, early and enthusiastic in their burst of energy, grew frustrated and short-fused.

“We’re not going to find it,” Linda said.

“Probably,” Fletcher said, “we have less chance than the ones in the outer ring.”

“We can go out there,” Jeremy declared.

“No, we can’t. I’m not being responsible for you clambering around in the dark. Senior-juniors are searching that.”

Jeremy’s shoulders slumped. The junior-juniors were tired to the point of exhaustion. They all had blisters.

And senior crew had found out, unofficially. A number had volunteered extra hours, and hiding places they’d known when they’d been young and foolish.

Some of those searches surprised the junior-juniors, that anyone but them did know those nooks and crannies.

Jake came, having gotten the general description, and said there’d been no stones in the recycling traps, which indicated it hadn’t gone into biomass, unless somebody had thought of that and removed the stones before chucking it into a disposal chute.

That was a logical place to search, one Fletcher hadn’t thought how to handle in terms of the chemistry; and Jake, the bioneer, had disposed of the question by something so basic his school-fed theory hadn’t even considered it.

Notes from all four of the captains turned up one by one in his personal pager, saying, essentially, that the captains were aware, and that official issues aside, if he wanted to discuss the matter, they stood ready to listen.

Fletcher didn’t know how to answer, so he delayed answering. The first impulse had been to say, Get me off this ship; and the second one had been a hesitancy to say what might not, even yet, answer where he wanted to go, or what he wanted to do.

He hadn’t expected the flurry of senior help in the search.

He hadn’t expected the junior-juniors, patching blisters, to keep looking.

He hadn’t expected the senior-juniors to show up in the mess hall, half-frozen from the ring skin, looking for hot coffee and looking exhausted as his own small crew. That included Chad, who avoided looking at him, who pointedly looked the other way when he stared.

It’s destroyed, he said to himself, and Chad’s scared to say so. It’s destroyed or it’s lost and Chad can’t find it.

But none of the senior-juniors talked much, least of all to him, and not that much to each other. There was no rec, meals were catch-as-catch-can, and no one associated together.

This is wrong, Fletcher said to himself, sitting in the A deck mess hall with a coffee cup cooling between his own hands. Jeremy had gotten himself a cup of coffee, and then Vince and Linda had, not their habit. Caffeine wouldn’t, Fletcher thought, improve Jeremy’s already hair-trigger nerves. He wasn’t sure any of the junior-juniors were used to it. But he drank it; and they drank it, a warm-up from the chill of places they’d searched.

Jeremy had fallen asleep yesterday night with the suddenness of a light going off. He’d lain awake with the increasingly heavy responsibility of the ship’s search lying on his pillow, and he thought, today, This is wrong , with the notion that if he stood up, said, Forget it, it’s lost, it may never turn up… he might free everyone, and relieve everyone’s nerves, and just let it pass.

He got up, finally, with the notion of doing exactly that, and immediately the junior-juniors wanted to jump up and follow.

“No,” he said. “An hour alone. All right? And don’t do anything stupid.”

“Yessir,” Jeremy said.

He went over to that other table, where Chad and Wayne and Connor were sitting. “Where’s JR?” he asked in a carefully neutral tone. “Do you have any notion?”

“Bridge,” Wayne said, “last I heard. What’s the problem?”

He couldn’t go to the bridge. No one could go there without an authorization.

“Thanks,” he said, frustrated in his resolution.

“What do you want?” Wayne asked, and he looked at Wayne, and the two he had most problem with, and took resolution in both hands.

“To stop this. Just give it up.”

“Why?” Wayne asked

“Because it’s getting nowhere! Somebody lost it. I accept that. Just everybody quit looking. It may turn up ten years from now. It may never turn up. That’s the way it is.”

“I’ll relay that to JR,” Wayne said carefully. Neither Chad nor Connor said anything. Chad did look at him, an angry look, a wary one. Connor didn’t do that much.

He went back to the juniors and sat down,

“We can’t give it up,” Jeremy said

“Even if we stop looking,” Linda said, “we can’t give it up.”

It was, he thought, the truth, however Linda meant it. He had the captains’ messages stacked up and waiting, that he hadn’t heard from Madelaine meant only that Madelaine was either under orders or trying to restrain herself, and in all the things that had happened aboard the ship, he could only fault a bad situation and a natural resentment.

It was natural that the senior-juniors wished he’d never come aboard; and maybe it was natural Jeremy and Madelaine and maybe the Old Man wanted him never to leave. He’d become the center of a situation he’d never wanted, and everything had gotten out of hand to the point it had damaged the ship.

Even if we stop looking we can’t give it up…

He knew now what a delicate, interconnected structure he’d arrived in, and how it had tried to fit him in, and how he’d damaged it without understanding it… irrevocably so, perhaps. Stopping the search wouldn’t cure it

Getting rid of him might relieve the pain, his and theirs, but it wouldn’t cure it. There wasn’t even an organized evening mess in which he could snag JR into private converse.

In another hour the intercom announced the docking schedule, and particulars of assignments, and they were in their quarters packing duffles reversed in the usual proportion of flash and work clothes: this time it was one dress outfit and the rest work blues.

“ This is James Robert Senior ,” the intercom said unexpectedly. “ We have completed cargo purchase and fueling arrangements prior to dock. Senior officers will be engaged in negotiations vital to the peace of the Alliance. We have been alert for any merchanter inbound from Esperance in the notion that such a ship might have information on the two ships who jumped close to us. Keep your eyes occasionally toward the station schedules and be aware that if such a ship should come from Esperance vector, the situation might change rapidly and dangerously. Be aware that this station has numerous black marketeers doing business on the docks and that they may feel we threaten their interests. Be alert. Do not violate the schedule and do not leave the accommodations except to come straight to the ship for work. The sleepover is the finest we were able to obtain, and it has some recreational facilities, but we do not believe there will be extensive time aside from sleep and meals. We will not stow any can we have not verified .

“ You are all by now aware that there has been an incident aboard unprecedented in this ship’s history. I call on all involved to set aside the matter for the duration of our stay, in the interests of all aboard, and I continue to express confidence that the parties involved will find it in their capacity to resolve the issue in a manner considerate of the ship’s best interests and traditions of honor.

“ Enjoy your stay .”

He had continued to fold clothing, Jeremy to tuck in small items like his tape player.

Neither of them said anything. He wished now he’d never reported the theft or made an issue. He said to himself he wanted it forgotten, beyond their next jump, that, in the way of mystical things, he’d gained all he could from his loss and stood to lose all he had, if he insisted on finding it.

The intercom droned on with assignments and shifts. The junior-juniors and Chad were at opposite ends of a twenty-four-hour clock. They went down to the assembly area and took their places, Vince and Linda attaching themselves from somewhere farther back in the large, rail-divided rec hall; and Madelaine and others noted their passage through the mob of cousins, giving them small pats on the shoulder, as others did with him. Fletcher ducked his head and studied the rail in front of him, not wanting to communicate. The junior-juniors stood fast about him through the procedures, like some fiercely protective bodyguard, until it was time for the section chiefs to go out and down to take care of customs.

It was, Fletcher discovered, not Pell, not Mariner. It looked more barren than Pell’s White Dock at the dead hours of alterday, as seedy as any between-shop alley in White. And it had a look of danger, the way White Dock had been dangerous, the domain of insystemers and cheap hustlers and those who wanted to sink in among them for safety.

Customs was a wave-through. For everyone.

Baggage pickup was fast. Everyone had packed as lightly as possible and bags came down the exit chute from cargo as if the handlers had slung them on six at a time.

“The bag-end of stations for sure,” he said to the junior-juniors when they set out for their sleepover, a short march across the docks to a frontage of gray-painted metal.

Definitely not Mariner. The promised Safe Harbor Inn was squeezed in between a bar’s neon light and a tattoo parlor.

Fifteen minutes later, with scant formality, they had their keys and found themselves sandwiched into what they’d called a suite on the second level—with a note from JR on his pager that occupants on the same floor were known smugglers and that senior staff would walk the whole junior-junior contingent to their duty shift every shift.

Their so-called luxury suite was one room, two beds, and a couch.

“God,” Vince cried. “This is brutal. We’re stuck in here?”

“We’ve got a vid,” Jeremy said in desperate cheerfulness, and turned it on. The program selection was dismal and, at one channel, Fletcher made a fast move to stand in front of the screen.

Then he thought… what the hell. They were spacer juniors. They’d tossed Linda in with him and Jeremy and Vince, and he figured it was because she was safer with them than elsewhere, tagging around after some preoccupied senior crewwoman and trying to catch up with her age-mates for duty.

“The hell with it all,” he said, and gave up on censorship with the vid. Then turned it off. “Yes, we’re stuck. I brought my tapes. Vince and Jeremy, the bed on the left, Linda, the right, I get the couch cushions and probably I’ve got the better bargain. We’ll splurge on supper, go to duty. It’s three days max.”

“Walking us to duty like babies,” Linda sighed, and collapsed on the end of the bed, her feet on her duffle. “Skuz.”

It was, Fletcher thought, the other side of the spacing life. It wasn’t all palaces. His mother had known places like Mariner. But this was like post-War Pell, this was like the apartment he’d shared with his mother, right down to the plumbing that rattled. It wasn’t a place he wanted to remember, in its details, the cheap scenic paneling. The place had had a plastic tri-d painting, pink flowers, right over the couch that was a makedown bed

And he’d gotten those couch cushions for his bed, on the floor. Odd thing to be nostalgic about. But that was how little space they’d had. He’d had to walk on the cushions to get past the arm of the couch, his mother had fitted him in that tightly against the wall. His nest, she said. And then when welfare complained, she’d gotten a bed for him, but he’d preferred the cushions, his homey and comfortable spot. So after all that fuss they kept the cot behind the couch and never set it up.

They ate supper, he and the juniors, they walked the only circuit they had, in the lobby, they played a handful of game offerings in the game parlor. At 1200 hours a party of Finity crew formed in the lobby and walked, in a group, to the dock, and to the cargo lock.

The instructions arrived, written, for each section head. He read them three times, because it made no particular sense to be emptying one container into the other. He went to the head of Technical over at the entry, a little sheepish.

“Are we emptying one can into another or is it something I’m missing in the instructions?”

“Vacuuming it from one to the other. That’s why we took on only food grade and powders.” Grace, Chief of Cargo Tech, the coat patch informed him. “Easier to clean the vacuum with powders.” He must have looked as bewildered as he felt, because Linda, who’d tagged him over to ask, nudged his arm.

“They can kind of put a foreign mass in stuff, even powder like flour, and they sort of make it assemble by remote, or sometimes it’s on a timer. It’s real nasty. But it’s got to have this little starter unit.”

“It blows up,” Grace said. “That’s why we’re analyzing the content on every can and sifting through everything. Security Red. There’s those with reason to wish we’d fail to reach our next port.”

“Because of the negotiations,” he said.

“Because of that, and because some just had rather on general principles that we didn’t exist.”

All the junior-juniors had gathered around. People wanted to blow up ships with kids on them. That was why the court had kept him off Finity . Maybe the court had saved his life. They talked about so many dead, the mothers of these three kids among them, dying in a decompression.

He didn’t ask. He lined the fractious juniors up to go in and get the coats they were supposed to have. The cans were sitting outside on the dock, huge containers, the size of small rooms. The message to the section heads said something like fifteen hundred of those cans.

And they were going to transfer cargo from one to the next so they could be sure of the contents?

He’d never been inside a ship’s hold. He’d only seen pictures. He went up the cargo personnel ramp, was glad to snatch a coat from the lockers beside the access and to see the juniors wrapped up, too, on the edge of a dark place with spotlights illuminating machinery, rows and rows of racks.

“Back there’s hard vacuum,” Jeremy said, pointing at another airlock with Danger written large in black and yellow. Machinery clanked and clashed as a can came in, swung along by a huge cradle. No place for kids, his head told him, but these three knew better than he did.

“You got to keep to the catwalks,” Vince yelled over the racket, breath frosting against the glare and the dark. Vince slapped a thin rail. “Here’s safe! Nothing’ll hit you in the head! Lean over the edge, wham! loader’ll take your head off!”

“Thanks for the warning,” he said under his breath, and said to himself of all shipboard jobs he never wanted, cargo was way ahead of laundry or galley scrub. His feet were growing numb just from standing on the metal. Contact with the rail leached warmth from his gloved hands. The proximity of a metal girder was palpable cold on the right side of his face. “Colder than hell’s hinges.”

“You got a button in your pocket lining,” Jeremy said, and he put his hand in and felt it. Heated coat. He found it a good thing.

They were mop-up, was what the duty sheet said. Every can had to be washed down and free of dust, as it paused before its trip into the hold. Cans that had been set down, behind the concealment of the hatch, had to be opened, the contents sampled, shifted to another can, and that can, its numbers re-recorded on the new manifest, then had to be picked up by the giant machinery, and shunted to their station while Parton and his aides were running the chemistry to prove it was two tons of dry yeast and nothing else.

The newly filled cans acquired dust in the process. Dust was the enemy of the machinery and it became a personal enemy. They took turns holding a flashlight to expose streaks on the surface, on which ice would form from condensation even yet, although the cold was drying the raw new air they’d pumped into the forward staging area. Ice slicked the catwalks, a rime hazardous as well as nuisanceful. Limbs grew wobbly with the cold, hands grew clumsy.

Fletcher called for relief and took the junior-juniors into the rest station to warm up with hot chocolate and sweet rolls and sandwiches, before it was back onto the line again.

“Wish we had that bubbly tub from Mariner,” Jeremy said, cold-stung and red-nosed over the rim of his cup. “I’d sure use it tonight.”

“I wish we had the desserts from Mariner,” Vince said.

“You and your desserts,” Linda said. “We’ll have to roll you aboard like one of the cans.”

“Not a chance,” Vince said. “I’m working it all off. A working man needs a lot of calories.”

“Man,” Linda gibed. “Oh, listen to us now.”

“Well, I do ,” Vince said.

Fletcher inhaled the steam off the hot chocolate and contemplated another trip out into the cold. He looked at the clock. They’d been on duty two hours.

They had four more to go.

The gathering in the Voyager Blue Section conference room was far smaller than at Mariner, hardbitten captains, two women, one man, who wanted to know why they’d been called, and what they had to do with Finity’s End .

“Got no guns, no cash, nothing but the necessaries,” the man in the trio said.

Carson was the name. Hannibal was the ship-name, a little freighter not on the Pell list of ordinary callers, but on Mariner’s regulars: JR had memorized the list, had seen the -s– and question mark beside both Hannibal and Frye’s Jacobite , the one that was sharing the sleepover with them. That -s– meant suspect . Jacobite did just a little too well, in their guesswork, to account for runs only between Mariner and Voyager and maybe Esperance at need, but Esperance was pushing it for a really marginal craft, no strain at all for Finity’s End .

There was reason the small ships took to trading in the shadows, bypassing dock charges, maximizing profits.

“We hope,” the Old Man began his assault, “that we have a good deal in the offing. We’ve got a problem, and we’ve got a solution, and let me explain the making-money part of it before I get to the cost. It’s not going to be clear profit, but it’s going to be a guarantee Voyager stays in business; it’s going to mandate your ships keep their routes, as the ones that have kept Voyager solvent thus far. There’s also going to be a repair fund, meaning credit available for the short-haulers. Mariner’s backing it. So’s Pell. Voyager stationmaster will speak for himself. We have a list of twenty-five small haulers that stay within this reach. Those ships will see protection.”

“The cost.”

“You serve this reach and you make a profit doing it. You keep the trade only on the docks and you pay the tariff.”

“We pay the tariff,” Hannibal said.

“On all trades,” the Old Man said, and there was a little silence. The captains liked the one part of it. Salvation for the small operator, vulnerable to downtime charges and repair charges, was inextricably linked to cession of ship’s rights. Anathema.

“Who’s going to say our competition pays the same?” That from Jamaica , captain Wells, whose eyes darted quickly from one side to the other in arguments. “Who’s inspecting? Finity , arguing to let station inspectors on our decks?”

Difficult point, JR thought. Difficult answer, but the Old Man didn’t pull the punches.

“They’ll pay,” the Old Man said, “because there’ll be a watch on the jump points.”

“No,” Hannibal said.

“You’re supplying Mazian,” the Old Man said, more blunt and more weary than he’d been at Mariner, and the captain of Hannibal sat back as JR registered a moment of alarm. “Not necessarily by intent,” the Old Man said in the next second. “But that’s where the black market’s going, and that’s why there’s going to be a watch at those jump points. The money that’s not going to the stations will have to get to the stations. And this is where the profit will be for you .”

Totally different style with these hardbitten captains than the Old Man had used at Mariner. JR took mental notes.

“We have an agreement in principle by Voyager, and the stationmaster will be here within the hour to swear to it: there will be provision for ships that register Voyager as their home port. Uniform dock charges, to pump money into Voyager and do needed repair. More freight coming in, going out, more loads, more profitable goods…”

“Too good to be true,” Jacobite said. “What if we sign and we comply and here comes a big fancy ship, say, Finity ’s size…”

“ You get preference on cargo. You’re registered here. You load first.”

“Voyager’s going to agree to that?” Clear disbelief.

“Voyager has agreed to that.”

“Way too good to be true,” Jamaica said. “Say I got a vane dusted to hell and gone, and I’m going to borrow money, get it fixed and the Alliance is going to come across with the money.”

“In effect, yes.”

“I’m already in hock to the bank.”

“The idea is to preserve the ships that preserve this station. The Alliance is not going to let a ship go, not yours, not any ship registered here. Fair charges, fair taxes, stations build up and modernize and so do the ships that serve them. You may have seen a Union ship go through here in the last few days. That did happen. The Union border is getting soft. Union trade will come through, possibly back through the Hinder Stars again.”

There was alarm. The smaller ships couldn’t make a jump like that. Then Jamaica said:

“They open and they shut and they open, I don’t ever bet on the Hinder Stars. Waste of money.”

“It’s getting to be a good bet, at least for the Earth trade. Chocolate. Tea. Coffee. Exotics of all sorts. Cyteen’s two accesses to trade are Mariner and Esperance. Voyager is right in the middle. If Esperance opened up a second access to the Hinder Stars and on to Earth, Voyager could be in a position to funnel goods along the corridor to Mariner, in a damned lucrative trade competing with Pell’s Earth route. If you survive the transition. That’s the plan. Shut down the black market, cut Mazian out of deals and the local merchanters in.”

There was consideration. There were thinking frowns, and a general pouring of real coffee, which Finity had provided for the meeting. JR moved to assist, and Bucklin set down a second pot to follow the first.

They were working as hard to sell three scruffy short-haulers on the plan as they’d worked to sell far larger ships on the concept.

But these ships were the black marketeers, the shadow traders. This was Mazian’s pipeline, among the others, and these captains were beginning to listen, and to run sums in their heads in the very shrewd way they’d dealt heretofore to keep their small ships going.

They wouldn’t say, aloud, we’ll try to do both, comply and maintain ties with Mazian. JR had the feeling that was exactly the thought in their heads.

But half compliance was better than no compliance, and half might become whole, if the system began to work.

He went outside to bring in another platter of doughnuts. Hannibal’s capacity for doughnuts was considerable, and Jacobite’s captain, in the habit of common spacers at buffet tables, had pocketed two.

“Loading’s going smoothly,” Bucklin found time to say. “We’ve moved ahead of schedule on that. But fueling’s going to take the time. The pump’s not that fast.”

“Figured,” JR said, and had. The high-speed pumps at Pell and Mariner were post-war. Practically nothing on Voyager was, except the missile defenses.

To a place like this, ships, if they would forego the shadow trade and pay standardized dock charges, offered more than a shot in the arm. Ships to follow them brought a transfusion of lifeblood to Voyager, which until now had seen ships just as soon trade in the dark of the jump-points as stay in its dingy sleepovers and spend money in its overpriced amusements. In the War, the honest trade had gotten thinner still, as Union had taken exception to merchanters supplying the Fleet and tried to cut off Voyager, as a pipeline to Mazian’s Fleet.

It had been one hell of a position for station and merchanters to be in, and one which Alliance merchanters resolved never to get into again. Abandon Voyager? Let Esperance slide into Cyteen’s control?

No. Starting from a blithe ignorance at Pell, JR had acquired a keen understanding of the reasons why small, moribund Voyager was a key piece in keeping Esperance in the Alliance, and keeping trade going between Mariner and Esperance inside Alliance space.

He knew now that Quen’s deal about the ship she wanted to build would put her in complete agreement with the position other Alliance captains had to take: new merchant ships were useless if all trade ebbed toward Cyteen; and shoring up Voyager would protect Pell’s territory more effectively than the launch of another Fleet.

That was why they’d agreed with her. The danger to the merchant trade now was in fact less the Fleet than a resurgence of Union shipbuilding with the clear aim of driving merchanters out of business.

So Voyager fish farms and an infusion of money to refurbish the Voyager docks were part and parcel of the new strategy. Voyager could become a market, a waystation: a station, given the wide gulf between itself and the Hinder Stars, that might revive the Hinder Stars for a third try at life, if they could establish a handful of ships capable of making that very long transit.

If the Hinder Stars could awake for a third incarnation free of pirate activity, there was a future for the smaller merchanters after all.

Get Voyager functioning, the Fleet cut off, Union agreeing not to compete with Alliance merchanters and get Union financial interests on the side of that merchanter traffic, and they had the disarmament verification problem solved. Alliance merchanters threaded through Union space, every pair of merchanter eyes and every contact with a Union station (to some minds in Union) as good as a Fleet spy recording their sensitive soft spots. But odd to say, they felt a lot the same about Union ships carrying cargo into Mariner and Viking. There were Unionside merchanters, honest merchanter Families whose routes had just happened to lie all inside Union territory, and who now got more favorable docking charges and privileges and state cargoes now that those ships had come out and joined the Alliance.

To his personal knowledge none of those Families had succumbed to Union influence and none would knowingly take aboard a Union operative. But love happened, and you could never be sure there wasn’t some stationer spouse of some fourteenth-in-line scan tech on a ship berthed next to you whose loyalties were suspect and who might be gathering data hand over fist.

That was the bright new age they’d entered.

He saw the years in which he might hold command on the bridge as a strange new age, a time of balances and forces held in check.

With less and less place for the skills of the War. The Old Man, who remembered the long-ago peace, had shown him at least the map of that future territory—and it was like nothing either of them had ever seen.

Bed, the couch cushions arranged on the floor as a bunk, or the bare carpet, if they’d had nothing else—a chance to lie horizontal came more welcome than any time in Fletcher’s life. The junior-juniors, past the giggle-stage and into complaints, mixed-gender accommodations and all, went down and fell mostly silent.

It was the second night, the second hard day, doing the same thing, over and over, until Fletcher saw can-surface and felt the protest in his feet even when he shut his eyes. The Vince-Jeremy argument about cold feet gave way to quiet from that quarter, darkness, and an exhaustion deeper than Fletcher had ever felt in his life.

Drunken spacers couldn’t rouse any resentment, careening against the door, or whatever they’d done outside. Fletcher just shut his eyes.

Hadn’t had supper. They’d had too many rest-area sandwiches and too much hot chocolate in the cargo hold office, and still burned off more energy than they’d taken in.

They’d showered once they got back to the Safe Harbor, was all, for the warmth, if nothing else, and Fletcher hoped the next shift got an immense amount done that they wouldn’t have to do.

He shut his eyes… plunged into black…

… wakened to dimmest light and twelve-year-old voices telling each other not to wake Fletcher.

In the next second he saw a flash of light on the wall, moving shadows against it, and heard the door shut. He rolled over, saw nothing but black, got up, and banged his shin on a table.

“System. Light!” he ordered the robot, and, seeing the beds vacant, and hearing nothing from the bathroom: “Jeremy? Dammit!”

He flung on clothes, not bothering with the thermal shirt, just the work blues and the boots, and headed for the lift. Which didn’t come.

He took the bare metal stairs and arrived down in the lobby. Third shift was coming in, a scatter of juniors.

Chad and Connor.

“Fletcher!” Connor said.

He ignored the hail and went into the dining room, hoping for junior-juniors in the press of spacers in the breakfast line.

“Fletcher.” Connor. And Chad.

“I don’t see the kids,” he said.

“What’d they do?” Connor wasn’t being sarcastic. It was concern. “Get past you?”

“Yes,” he muttered, and went out into the lobby again, looking for twelve-year-olds in the press of spacers in dingy coveralls with non– Finity patches.

They were at the vending machines. Linda had a sealed cup in her hands.

“You got to watch them,” Connor said at his shoulder.

“I was watching them,” he retorted, wanting nothing to do with his help.

He went over to claim the kids.

“You weren’t supposed to get up yet,” Linda said, spotting him. “We were bringing you hot chocolate.”