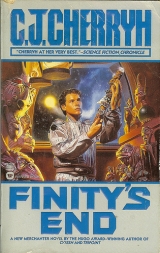

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

He decided he could relax a little. The gossip among the cook-staff still said the Union carrier that had startled them on entry was watching their backs like a station cop on dockside, and it still didn’t seem to be bad news: there was no move to hinder them, and if there’d been any Mazianni about, they’d have been scared off by the Union presence, so they could dismiss that fear, too.

He was, he realized, already falling into a sense of expectations, after all expectations in his life had been ripped away from him. Vince and Linda were, hour by hour, tolerable nuisances, Jeremy was his reliable guide and general cue on the things he had to learn, besides being a cheerful, decent sort of kid when he wasn’t blowing up imaginary pirates. Jeff the cook didn’t care if he nabbed an extra roll, or, for that matter, if anybody did. It was like deciding to enjoy the fruit desserts. Life in general, he decided, was just fairly well tolerable if he flung himself into his work and didn’t think too hard or long about where he was.

He even found himself caring about this job, enough to anticipate what Jeff wanted and to try to win Jeff’s good humor. No matter how he’d previously, at Pell, resolved to stay sullen and just to go through the motions in his duties for his newest family, he found there was no sense sabotaging an effort that fed them fruit and spice desserts. Jeff Neihart appreciated with a pleasant grin the fact that he stacked things straight and double-checked the latches the same as people who were born here. It was worth a little effort he hadn’t planned to give, and he ended up doing things the careful way he could do something when he cared.

Disorientation still struck occasionally, but those occasions were diminishmg. Yes, he was in space, which he’d dreaded, but he wasn’t in space: it was just a comfortable, spice smelling kitchen full of busy people.

When, late in the shift, he took a break, he sat down to a cup of real coffee at a mess hall table. He understood it was real coffee, for the first time in his life, and he drank it, rolling the taste around on his tongue and telling himself… well… it was richer than synth coffee. Different. Another thing he daren’t get too used to.

A ship, he was discovering, skimmed some real fancy items for its own use, and didn’t count the cost quite the way station shops would. On this ship, while they had it, Jeff said, they had it and they should enjoy it.

There were points to this ship business that, really, truly, weren’t half bad. A year was a long time to leave home but not an insurmountable time. There were worse things to have happened. A year to catch his balance, pass his eighteenth year, gain his majority…

Jeremy came up and leaned on the table. “Madelaine wants you.”

“Who’s that?” he asked across the coffee cup.

“Legal.”

His stomach dropped, no matter that there wasn’t anything Legal Affairs could possibly do to him now. He swallowed a hot mouthful of coffee and burned his throat so he winced.

“Why?”

“I don’t know. Probably papers to clear up. She’s up on B deck. Want me to walk you there?”

He didn’t. It was adult crew and he didn’t want any witnesses to his troubles, particularly among the juniors. Particularly his roommate. All the old alarms were going off in his gut. “What’s the number up there?”

“I think it’s B8. Should be. If it isn’t, it’s not further than B10.”

“I can find it,” he said. He drank the rest of the coffee, but with a burned mouth it didn’t taste as good, and the pain of his throat lingered almost to the point of tears, spoiling what had been a good experience. He got up and went down the corridor to the lift he knew went to B deck.

It was a fast lift. Just straight up, no sideways about it, and up to a level where the Rules said he shouldn’t be except as ordered. It was a carpeted blue corridor: downstairs was tiled. It was ivory and blue and mauve wall panels.

Really the executive level, he said to himself. This part of the ship looked as rich as Finity was. So this was what you lived like when you got to be senior executive crew… and lawyers were certainly part of the essentials. Finity didn’t even need to hire theirs. It was one more damn cousin, and since lawyers had been part and parcel of his life up till now, he figured it was time to get to know this one.

This one—who’d stalked him for seventeen years and who he suddenly figured was to blame, seeing how long spacers lived, for every misery in his life.

Madelaine? Such an innocent name. Now he knew who he hated.

It was B9. He found Legal Affairs on a plaque outside, and walked into an office occupied by a young man in casuals one might see in a station office, not the workaday jump suit they wore down where the less profitable work of the ship got done.

“You’re not Madelaine,” he observed sourly.

“Fletcher.” The young man stood up, offered a hand, and he took it. “Glad to meet you. I’m Blue. That’s Henry B. But Blue serves, don’t ask why. Madelaine’s expecting you. ”

“Thanks,” he said, and the young man named Blue showed him into the executive office, facing a desk the like of which he’d never seen. Solid wood. Fancy electronics. A gray dragon of a woman with short-cropped hair and ice-blue eyes.

“Hello,” she said, and stood up, came around the desk, and offered a cool, limp hand, a kind of grip he detested.

She looked maybe sixty, old enough that he knew beyond a doubt she was one of the lawyers behind his problems and that apparent sixty probably represented a hundred. She was cheerful. He wasn’t.

“So what’s this about?” he asked. “Somebody forget to sign something?” He feigned delight. “You’ve changed your minds and you’re sending me home?”

Unflapped, she picked up a blue passport from off her desk and handed it to him. “This is yours. Keep it and don’t mislay it. I can reissue but I get surly about it.”

“Thanks.” He tucked it in his pocket and was ready to leave.

“Sit down.—So how are you getting along?”

She knew he wasn’t happy here and didn’t give a damn.

Good, he thought, and sat. That judgment helped pull his temper back to level and gave him command of his nerves. It was another lawyer. The long-term enemy, the enemy he’d never met, but always knew directed his life. She was cool as ice.

He could be uncommunicative, too. His lawyers had taught him: don’t fidget, look at the judge, don’t get angry. And he wasn’t. Not by half. “Am I having a good time?” he countered her as she sat down and faced him across her desk, her computer full of business that had to be more important to her than his welfare. “No. Will I have a good time? No. I’m not happy about this and I never will be. But here we are until we’re back again.”

“I know it’s a hard adjustment.”

“And you had to interfere in my life.” He hadn’t found anybody aboard he could specifically blame. He’d have expected something official from the senior captain, at least a face-to-face meeting, and hadn’t gotten it—as if they’d snatched him up, and now that they’d demonstrated they could, they had no further interest in him. He resented that on some lower level of his mind. He wouldn’t have unloaded the baggage in her office, he hadn’t intended to, but, damn it, she asked. She wanted him to sit down and unburden his soul to her, in lieu of the real authority on this ship—when she was the person, the one person directly responsible for ten and more years of lawsuits and grief in his life, not to mention present circumstances. He drew a deep breath and fired all he had. “My mother was a no-good drughead who ducked out on me, you wouldn’t leave me in peace, and here I am, just happy as you can imagine about it.”

“Your mother had no choice in being where she was. She did have a choice in refusing to give up your Finity citizenship.”

“She died! And excuse me, but what in hell did you think you were doing, ripping up every situation I ever worked out for myself?”

There was a fairly long silence. The face that stared at him was less friendly than the hisa watchers and just as still.

“I’m sorry you wanted the station, but you weren’t born to the station, Fletcher, and that’s a fact that neither of us controlled. This universe doesn’t let you just float free, you know. There’s a question of citizenship, your birthright to be in a particular place, and birth doesn’t make you a Pell citizen. You were always ours, financially, legally, nationally. Francesca wouldn’t let you be theirs. She wanted you here. They just wouldn’t let you leave.”

“The damn courts, you mean.” In the low opinion he held of Pell courts they could possibly find one small point of agreement. And she hadn’t flared back at him, had, lawyeresque, held her equilibrium. He even began to think she might not be so bad, the way nobody on the whole ship had really turned out to be an enemy. In giving him Jeremy, they’d left him nothing to fight. Nothing to object to. In sending him here, to this woman, they gave him, again, nobody he could fight with the anger he had built up. It was robbery, of a kind he only now identified, that he really didn’t want to hurt this woman.

“The damned courts,” she said quietly, “yes, exactly so.”

“Did you pay fourteen million?”

“You heard about that.”

“Damn—excuse me—right I heard.”

“They sued us to buy you a station-share and kept the case in limbo; meanwhile, their own Children’s Court wouldn’t release you to us so long as the War continued, or so long as we were working with Norway . And we don’t give up our own, young sir. Learn that first off. For good or for ill, this ship’s deck is sovereign territory and we don’t give up our own and pay a fourteen million credit charge on top of the outrage. If you want to know who put obstacles in your path, yes, the Pell courts, who saw no reason to credit this ship for the very fact there is a Pell judiciary and not an outpost of Union justice in its place. Your mother fought tooth and nail to maintain custody of you. We would have taken you at any pass through this system. Pell courts thought otherwise, but they gave you no rights within Pell’s law.”

It had been a good day going, before Madelaine the lawyer called him in to tell him what great favors they’d done him. Nothing to fight? She’d given him something. Fourteen million credits and his life at issue. Civilization was cancelled for the day. And he turned honest. “I don’t want to be here. Doesn’t that count ?”

“But the fact is, you had no right to be at Pell, either.”

“I had every right!”

“Not the important right. Not the legal right. And they wouldn’t give it to you unless we paid for it because your rights lie on this ship where, from your mother, you have citizenship and financial rights.”

“Well, that’s not my fault. I don’t owe this ship. And I damned sure don’t owe my mother. She never did anything but mess up my life.”

“She had little enough of her own. Your mother was my daughter’s child. Your grandmother died at Olympus. Unfortunately for both of us, it seems, I’m your great-grandmother. Your closest living relative.”

He’d fired off his mouth without knowing what he was firing at. He’d insulted his mother as he was in the habit of doing with strangers rather than having others do the sneering and the blaming and him do the defending. Lifelong habit, and he’d just done it to the wrong person. He’d wondered what it would be like to have a grandmother, or a godmother, back when he was reading nursery rhymes. Stationers had them. If he had one he wouldn’t ever be in foster homes. Would he?

His godmother, however, wasn’t a soft, plump woman with a wand and a pumpkinful of mice. It was a spacefaring lawyer with eyes that bored right through you. And not his god- mother, either. Not even his grandmother. His grandmother’s mother , two generations back.

“Francesca died when you were five,” Madelaine said “That’s too young really to have known her. Or to have formed a good judgment.”

He was prepared to back up a couple of squares and admit he’d been too quick. But her judgment of him drew a shake of his head. He couldn’t help it. “No. I was there. I remember .”

He remembered police, and his mother lying on the bed, not moving. He remembered realizing something was wrong with her. Her hand had been cold, terribly cold when he’d touched it. He’d known that wasn’t right. And he’d called the emergency squad. He remembered textures. Sensations. Everything, every tiniest detail, was branded in his consciousness.

“She was a good woman,” Madelaine said. “Good at what she did. She’d taken jump drugs all her life with no trouble. The simple fact was, she was pregnant, too late to abort, too early to deliver except to a birthlab, which she chose not to do; we knew what we were facing—it’s declassified now, so we can talk about it. But it wasn’t then, and going to a birthlab at her stage of pregnancy—we didn’t have the time for her to do that and recover. We just couldn’t wait for her, if she did it without us she’d still be stranded ashore, and she was in a hell of a mess. There was nothing for anyone but bad choices. We said we’d be back in a year. That didn’t happen. We missed our appointment with her, and she crashed. Just crashed, physiologically, psychologically. Depression sometimes follows a birth. She started self-medicating. The hyprazine, particularly the hyprazine, if you’ve taken it in jump, it gives you an illusion of being in space, and that’s what you take when you’re pregnant. That illusion was what she was after, Fletcher. Just so you know.”

“You and JR have been talking. Right?”

Madelaine shook her head. “No. We haven’t. What about?”

“The truth—” He could hardly breathe. He kept his voice calm. “She kept sending me to welfare—and getting me back—until she finally went out on a trip and never came down. And left me tangled in the damn court system. Then they couldn’t put me anywhere permanent and let anybody get attached to me because you kept suing the station. Let me tell you. I made it through six foster-families, five of them before I was fifteen. I made it through school. I made it through the honors program and into graduate. I licensed to work on Downbelow in Planetary Science, which is what I want to do, and where you called me from, and where I left everything I care about. And you come along and jerk me up and out of that to do your damn laundry and scrub mess hall tables, because you could do that and I’m your property! Well, screw all of you! I’m trying to keep my head straight because I know we can’t turn this ship around, I haven’t got money to buy passage on any other ship, and I have to live out this year, but that’s all ! That’s all . Because when we get back to Pell I’m going to sue you to get off this ship.”

“It still won’t give you Pell citizenship.”

It failed to knock the wind out of him, as she clearly expected. He didn’t want to tell her about Quen’s promise to him. She’d be the lawyer fighting him. He’d already been stupid and said too much. His lawyers would certainly have told him so.

“I had a girl back there,” he said.

“Oh, is that it?”

“No! That’s not it. It’s not all it is.” Naturally they wanted to wrap all his problems up in that. But what he felt wouldn’t be understandable to people who didn’t know what there was on a planet. He’d had a grandmother. She’d died. A lot of people on this ship had died… along with Jeremy’s close relatives. And Madelaine– his grandmother… his great- grandmother—just stared at him, maybe amused, maybe hurt by the truth he’d told, maybe not giving a damn for anything but the ship’s fourteen million. Since his mother died he’d never had to deal with anybody who owned the same set of emotional entanglements to him that his mother had had, and then he’d been five. Slowly the emotional shock of meeting this woman reached through to him, the feeling of an emotional pain somewhere he wasn’t sure of, bone-deep and about to become acute, and tangled somewhere in his mother’s death.

“I was in Planetary Studies,” he said. “That doesn’t mean anything here. But it mattered to me. It mattered everything to me.”

“The stationmaster told us what you’d done. Both your extraordinary work to get into the program, and the ruinous thing you did at the end.” Madelaine’s face was sober. Her hands were steepled loosely before her, a tangle of fingers, an attitude that somehow echoed a habit of someone else—his mother—he wasn’t sure. “Fact is, in your tender love of the planet, you broke laws, you fractured rules designed to protect it and the downers from the well-meaning and the callous users. I’m interested in why you’d do such a thing.”

The lawyer. Wanting to know about laws. And asking into what wasn’t her business, except that the question also involved his attitude toward rules-following, his behavior in a ship full of critical procedures. He was tempted to lie, to make things far worse than they were.

But he didn’t want to find himself restricted from the freedom he did have, either.

“Did you have a reason for running off from the Base?” she pursued, and he tried to organize his thoughts to give her the answer she’d both believe and take for reassurance.

“Being pushed further than you can push me now,” he said. “Further than anyone can ever push me again. That’s all. You can only lose so much.”

“Were you thinking of suicide?”

“Maybe. Maybe not.”

“Did you care about the downers? The stationmaster said you’d been consorting rather closely with two of them.”

Bianca talked . The information hit him like a hammer blow.

And then, on a next and shaky breath, Of course Bianca talked. I was gone. She had a right to talk . It was nothing but expected—only the ruin of something else important. Another support of his life kicked out from under him.

She was scared. She was involved and I involved her. A Family girl with a Family on her back. Sure, she had to get straight with them. I had to be the one at fault. I was gone, she had to be practical about it.

He’d hoped for a little more fortitude from her. Just a little heroism. But she’d saved her own hide. Everyone did, when the chips came down.

“Despite your heritage,—you trained to work with the downers,” Madelaine asked sharply. “Why?”

“Because—” He almost said, Because I love them, but he wasn’t going to let that information loose. Because I never thought you’d get me away from Pell. Never give a psych or a lawyer a handle to hold to. Not a real one. “Because they’re different. Because I don’t like human beings much . How’s that?”

“Sad if true.”

“Downers don’t kidnap people.”

“And, as I know from brief experience, they don’t understand human relationships. It’s very much the contrary of what you’re supposed to be doing with them. But you were intent on your own reasons.”

“Reasons that they invited me to be with them. For years. I know the downers, I know the two I dealt with.”

“You know them better than the scientists and the researchers. You know them well enough to defy the rules and endanger a half a hundred rescuers”

“It was their choice to be out there chasing me.”

“Was it?” A shake of the lawyer’s head. “Fletcher, I think you’re better than that. Difficult. So was my granddaughter. It’s why you were born. She was in love, in a year when any child was a hostage to fate. She knew that. She ran a risk.”

In love.

It’s why you were born.

He had a merchanter for a mother and that meant he had no father. It was one of the facts of his life: he had no father. How dare she throw that out for bait? His mother knew who the father was and it wasn’t some chance encounter in a sleep-over?

He wouldn’t take that bait. Not if his life depended on it.

He stood up. “I’ve got work to do.”

Madelaine looked at him as if he were something on her agenda. No longer cool, no longer remote. “God, you’re like Francesca.”

That, too, was a gut blow. He didn’t know how hard until he’d walked out, through the office, past the cousin named Blue, and out into the fancy carpeted corridor.

Like Francesca . She looked at him with age-crinkled eyes and dismissed his best shot with God, you’re like Francesca …

He wasn’t like his mother. He wasn’t anybody’s copy. His mother hadn’t been like him.

She was in love …

He’d not known his mother when she was seventeen. She might have sat in that same chair. She might have used this same lift. Walked these same corridors…

Been in love…

He had a father somewhere. His great-grandmother knew who it was. She had all the names, and held them as bait to draw him out, to get pieces of him in her reach, more deft than any psych.

He was used to the station as his mother’s venue. That was where she’d lived, and Finity’s End was where she’d come from .

But this corridor, these places, all this was a place she’d walked in, too, like some hidden room of her life where she’d been as young as he was now and where people remembered her in the same awkward, mistake-making years he was trying his best to grow out of.

It shook him.

It totally revised his concept of where he was and what he’d come from and who that seventeen-year-old twelve-year-old he roomed with really might have been to him. Here he was wandering around blind, in her young years, meeting people who’d wanted him because they’d lost her and to whom the whole reality of the station was a locked room they couldn’t get into, either. And Jeremy was the bridge. Jeremy was the might-have-been, the one he’d always have been with. His mother would be dead, maybe, with Jeremy’s mother, with half the people on the ship… and things would be a lot the same, but different, vastly different, too.

He rode the lift back to A deck and walked back where he’d come from. His nerves weren’t up to a challenge of things-as-they-were or a confrontation with Madelaine Neihart. He just wanted to go back to the mess hall and to Jeremy, that was all—even to go back to Vince and Linda. He couldn’t feel the ship moving, but they were shooting unthinkably fast toward the nadir of the Tripoint mass-point, where another event he didn’t understand would happen and they’d more than accelerate: they’d plunge a second time out of the known universe into a state his mother had chosen to live in, that she’d ultimately chosen to die in.

He’d failed that unit in his physics class—how the universe didn’t like the state they’d be in, and spat them out reliably somewhere else. He agreed with the universe: he didn’t like the state they’d be in and he didn’t want to imagine it. He didn’t know whether he could understand it, but when he’d had to study it, he’d pleaded with his physics instructor he didn’t want to take that tape again, please God, he didn’t want to… and the psychs had gotten into it. Finally the school had exempted him and let him study it and just barely pass it realtime, with pencil and paper, because the psychs said there were special psychological reasons that the instructor and the school weren’t equipped to deal with. They’d offered to help him deal with it. And he’d said no. And somehow it hadn’t come up again.

No more exemption, now. No more psychs to step in and say let Fletcher alone: he can’t deal with it. The court had forgotten all about that fear when it gave him up and stripped him of his Pell ID. His bitter guess was that it had stopped mattering to most people the second somebody mentioned fourteen million credits. Quen had reached out and tapped some judge on the shoulder and said, Let them have him this time.

And ironically, completely unexpectedly, the only person in the whole affair who cared—personally, cared, as it turned out—might have been the lawyer, Madelaine. The crew at large, meanwhile, didn’t know what he’d grown into, but thought the courts were holding from them some poor stupid kid it was their right to have, a kid whose spacer heritage would leap to the fore and instantly make him love them.

The ship unfortunately didn’t turn around to undo its mistakes. It only went forward and it didn’t stop for anything, that was what that long-ago physics tape had told him… the universe abhorred their situation half in hyperspace and half here and spat their bubble along the interface until a mass-point snatched them into its gravity and jerked their bubble remorselessly flat. When he thought about it, walking a corridor on a ship courting that event, the space that connected him to Pell felt stretched thinner and thinner, as if his whole universe could just tear and vanish.

His mother had died like that, hadn’t she? Her mind had just—stretched thin until one day there wasn’t enough left to get her home again.

Madelaine had all the wit he hoped his mother had had, needle-sharp and quick as he imagined now his mother might have been if she hadn’t been out on drugs and if he hadn’t been a feckless five-year-old. He couldn’t ever know her, clear-eyed—couldn’t ever sit in a room with her as he’d just sat with Madelaine, to have clear memories, or to sort out her pluses and minuses. He had memories of his mother being happy, and smiling, but he’d told himself in the maturer, more brutal judgment of his teenage years that those had all been days when she’d been high as the drugs could make her and still function—when the body was on Pell Station, but she wasn’t.

Love? She’d exuded just enough to rip the guts out of a kid. She loved somebody whose name Madelaine dangled before him? Had his kid?

Then why in hell had she lost herself in drug-hazed space? Post-birth depression? He wished it were that simple.

He went back to the mess hall and, finding there was nothing doing at the moment, had a soft drink. They were free. It was one benefit of a situation that felt, again, like the trap it was.

“So what’d Legal want?” Jeremy wanted to know,

“Just passport stuff,” he said. He didn’t talk about it. He didn’t want Jeremy for a confidant on this point. He didn’t at all want Vince and Linda, who were lurking for gossip. If Vince had opened his mouth right then, he’d have hit him.

He fought for calm. He tried to settle down and just go numb about the situation, telling himself that a year, like all other periods of time, would pass. He’d learned to wait in doctors’ offices, in psychiatrists’ offices, in court. “Don’t fidget,” the adult of the month would say, and he’d stay still. When he stayed still nobody noticed him. A year was long, but his fight to get to Downbelow had been longer. He did know how to win by waiting. Don’t feel anything. Don’t say much. Don’t engage anybody the way he’d engaged the lawyer. He’d made the one mistake up in Madeline’s office… made the kind of mistake that gave manipulative people and lawyers levers to use.

No. She’d already known him, before he ever walked in that door. He was her great-grandson , and she’d lost her daughter and her granddaughter and now she wanted a try at him, seeing his mother in him. That was something he’d never faced. She was his honest-to-God real great-grandmother, and his mother had lived on this ship.

She’d just died on Pell.

Chapter 11

The shift went to bed, an exhausted mainnight in which visions of rain-veiled river danced in Fletcher’s eyes; and playing cards cascaded like raindrops, inextricably woven images, in which somehow he owed days, not hours, and in which he chased Jeremy through tunnels first of earth and then of garishly lit steel and pipe, the latter of which looked miraculously like the tunnels on Pell.

Next morning it was back to the galley before maindawn, help Jeff set out the breakfast trays and get the carts up to B deck, but they were still cooking huge casseroles for next jump… things that could warm up in a hurry, a lot of red pepper involved. Taste was pretty dim after jump, so Jeff said, and by Fletcher’s estimation it was true; spicy things perked up the appetite. While they were doing that, they’d had no further alarms, no changes in velocity. Jeff said the ship’s long, even run under inertia would give them the chance to get some baking done. Cakes in the oven during a high-K run were doomed, so Jeff said.

So whenever they hit an onboard stretch where they could spread out and cook, they cooked for all they were worth: fancy pastries, casseroles, pies, trays of pasta and individual packets for those hours people came in scattered There were onions and fish from Pell, there was keis and synth ham, there was cabbage and couscous and what they called animal protein, which was a kitchen secret nobody should have to look at before it cooked. It came in pieces and mostly the cook-staff ground it. There was rice from Earth and yellow grain from Pell; there were sauces, there were gravies, there were fruit jellies that came from Downbelow and wine solids and spices and yeasts that came from Earth. There were keis sandwiches, fish sandwiches, and pro-paste sandwiches which Fletcher swore he’d never eat again in his life; there were pickles and syrups and stuffed pasta, string pasta, puff breads and flat-breads and meal and pro-paste pepper rolls with hot sauce, and there were sausage rollups, which were their lunch, and keis and ham rollups which were supper. The galley had rung with the battering of pans and trays, swum in pots of sauce that went steaming into forms of given sizes and had to be trundled on carts into the galley lift, where in coats you put the stuff in deep-freeze on the very outer level of the rim in what they called the skin. Out there among the structural elements of the passenger ring, cold was the natural, cheap environment, requiring only a rack for storage, no mechanism but a light; and you felt that cold burning right through your boot-soles when you walked the grids. Fletcher made one trip down with Jeff just to see what it was like, his closest approach to the uncompromising night outside the hull; he was glad to get back up into warmth and light of the ring.

All this day they worked on sandwiches, and of course, tastes of the current batch. Nobody on regular cook-staff ever seemed to eat a meal: they sampled; and the last job they put together, just before supper, was a giant pyramid of tasty little sandwiches and another of sweets. Which to Fletcher’s disappointment didn’t turn up on their menu. It went to B deck.