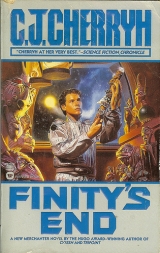

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

But, along with the mischief he hadn’t gotten into any longer, had gone the fellowship he hadn’t had in the competitive Honors program. He’d invested in no friendly companionship since he’d gotten involved so deeply in his goals, except, well, Bianca, which had started out with a rush of something electric. But no guys, no one to play a round of cards with or hang about rec with. He’d evaded females in the crew. He’d let himself fall back into an earlier time when girls were something the guys all viewed from a distance, when guys were mostly occupied with looking good, not yet obsessed with hoping their inadequacies didn’t show… he’d been through all of it, and he could look back with, oh, two whole years’ perspective on the really paranoid stage of his life.

And maybe—he decided—maybe dealing with small-sized Jeremy in that sense felt like a drop back into innocence and omnipotence.

Like revisiting his own brat-kid phase, when vid-games and running the tunnels had been his total obsession. Getting away with it. Telling your friends how wonderful you were. Yes, he grew tired of hearing blow-by-blow accounts of maze-monsters and flying devils while Jeremy was beating him at cards, and the words wild and dead-on and decadent were beginning to make his nerves twitch; but there was something genuine and real in Jeremy that made him put up with the rough edges and almost regret that he’d lose Jeremy when his year of slavery was up. A few years ago, bitter and sullen with changes in his living arrangements, he’d have declined to give a damn—or to invest in a quasi-brother he’d lose. But he’d grown up past that; he’d had his experience with the Wilsons, and finally the Program; and somewhere in the mix he’d learned there was something you gained from the people that chance and the courts flung you up against, never a big gain, but something.

So, for all those tentative reasons, walking back to mess, he decided he liked his designated almost-brother, this round, among all the foster-brothers they’d tried to foist off on him. And if Vince leaned on Jeremy again tomorrow, he’d rattle Vince’s teeth with no real effort and damn the consequences.

They played cards in the rec hall after supper this first evening in Mariner system, and he won his time back from Jeremy plus six hours. Jeremy blew a hand. That was something. Or he was getting suddenly, measurably better.

“Want to play a round?” It was one of the senior-juniors coming up behind his shoulder as he collected the cards. He’d forgotten the name, but the convenient patch on the jumpsuit said, Chad .

Jeremy scrambled up from the chair when Chad asked, dead-serious and looking worried. The room was mixed company, seniors out of engineering watching a vid, a couple of other card games, the senior-juniors over in the corner shooting vid-games, and this guy, one of their group, wanted to play.

It wasn’t right, Jeremy’s behavior said it wasn’t right.

“Maybe you’d better play Jeremy,” Fletcher said, “He’s better.”

Chad settled into the chair anyway, determined to have his way. Chad looked maybe a little younger than JR, not much, big, for the body-age. Chad picked up the cards and dealt them. The stakes were already laid: get up and walk off from this guy, or pick up the cards. Jeremy’s distress advised him this was somebody to worry about. He picked up the cards, hoping he could score that way.

Chad won the hand, a lapse of his concentration, his own fault. The guy didn’t talk, didn’t ask anything, just played a hand and won it. They’d bet an hour.

“My hour,” Chad said. “You clean my room tomorrow, junior-junior.”

“I guess I do,” he said. He’d lost, fair and square. He didn’t like it, but he’d played the game. He’d satisfied Chad’s little power-play, didn’t want another hand, in any foolish notion he could win it back against a good, a very good card player. He got up and left, and Jeremy caught him up in the corridor, not saying anything.

He felt he’d been played for the fool, though he was grateful for Jeremy’s cues, and didn’t want to talk about the bloody details of the encounter. More than embarrassed, he was angry. Chad was one of JR’s hangers-on, crew, cronies, whatever that assortment amounted to, and JR hadn’t been there; but at the distance of the corridor, he saw the game beneath the game, and he knew winning against Chad wouldn’t have been a sign of peace.

“Did he cheat?” he asked Jeremy. He didn’t think so, but he wasn’t sure he’d have caught it, and he wanted to know that, bottom-level.

“No,” Jeremy said, “but he’s pretty good.”

It was better than his suspicion, but it didn’t much improve his mood “Why don’t you go on back?” he said. “There’s no point. I’m going to bed.”

“Me, too,” Jeremy said, for whatever reason, maybe that things weren’t entirely comfortable for a roommate of his in the rec hall right now. There’d been a pissing-match going on. My skull’s thicker than yours head-butting. And why Chad had chosen to come over to their table and pick on him was a question, but it wasn’t a pleasant question.

They got to the cabin, undressed.

“When we get to Mariner, you know,” Jeremy said, awkwardly enthusiastic, “there’s supposed to be this sort of aquarium place. It’s wild. Really worth seeing, what I hear. ”

“Yeah.”

“Well, we could kind of go, you know.”

He let his surly mood spill over on Jeremy and Jeremy was trying to make the best of it. Least of anybody on the ship was Jeremy responsible for Chad’s unprovoked attack on him.

He sat down on the bed; he thought about aquariums and Old River and how the fish had used to come up in the shallows, odd flat creatures with long noses. Melody had told him the name, but like no few hisa words, it was hisses and spits. They had an aquarium on Pell, too.

But it was an offer. It was something to do. Mostly he wanted to send his letters home. He didn’t want Chad or anybody else setting him up for something. And the coming liberty was a time when they might be out from under officers’ observation.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m kind of in a mood.”

“Yeah,” Jeremy said.

“You know I didn’t want to be here. It’s not my fault.”

“Yeah,” Jeremy said. “But you’re all right, you know. I wish you’d been here all along.”

He didn’t. Especially tonight. But he couldn’t say it to Jeremy’s earnest, offering face. There was the kid, the twelve-year-old man, the—whatever Jeremy was—who wanted to go with Mallory and fight against the Fleet, the kid who got so hyped on vid-games he shook and jerked with nerves, and who wanted to tour an aquarium on Mariner—probably, Fletcher thought, a whole lot more exotic to Jeremy than it was to him. Jeremy shared what he wanted to do. Shared a bit of himself.

Wished he’d had his company. That was saying something.

And because the moment was heavy and fraught with might-have-been’s, he ducked Jeremy’s earnest look and bent down instead and pulled open his under-bunk storage.

Where more than next morning’s socks resided. Where what was important to him resided.

In that moment of emotional confidences he took the chance, dug into the back of it and took out what Jeremy probably had never seen, something hands had made that weren’t human hands.

“What’s that?” Jeremy asked in astonishment, as he sat up and brought out the spirit stick. The cords unwound, feathers settling softly in the air, and the unfurling cords revealing the carvings in wood.

“Something someone gave me,” he said. He was defensive of it, and all it was to him. He thought to this moment he was a fool for unveiling it. But Jeremy’s reaction was more than he expected. It wasn’t puzzlement. It was awe, amazement, everything he looked for in someone who’d know what he was looking at and appreciate what he treasured.

“It’s hisa work,” Jeremy said. “Where’d you get it?”

“It was a gift to me. That’s where I lived. That’s what I did. That’s what I worked all my life to get into.” He handed it across the narrow gap and Jeremy took it carefully in his hands, stick, cords, feathers, and all.

Jeremy handled it ever so carefully, looked at the carvings, at the cords, fingered the wood, and then looked closely at a feather, stroking it with his fingers. “I figure about the cords, maybe, but how’d they make this ?”

He didn’t know what Jeremy was talking about for a moment, and then by Jeremy’s fingers on the center spine and the edges of the feather he realized. “It’s a feather ,” he said, hiding amusement, and Jeremy instantly made his hands gentler on the object.

“You mean like it came off a bird?”

“Not quite like the birds on Earth. They don’t fly much. They kind of glide. Some stay mostly on the ground. Downbelow birds.”

“I never saw a feather close up,” Jeremy said. “It’s soft.”

“Feathers from two kinds of birds. The wood comes from a little bush that grows on the riverbank. Cords are out of grasses. You soak it and put a stick in it and twist real hard while it’s wet and it makes cord. There’s a trick to sticking the next piece in just as you’re running out of the last one, so they make a kind of overlay in the twist. I’ve watched them do it. They don’t braid, that’s not something they invented. But they do this twist technique. If you do a lot of them, you’ve got rope.”

“Wild,” Jeremy said, and fingered the cord and, irresistibly, the feathers. “That’s really wild. I’ve seen vids of birds. I never saw a feather, like, by itself. Just from a distance. ”

“They fall off all the time. You’re not supposed to collect them. Hisa do. But humans can’t collect them.”

“A bird with its feathers falling off.” Jeremy thought that was funny.

So did he. “Not all at the same time. Like your hair falls out in the shower. A piece gets tired and falls out and a new one grows. It’s kind of related to hair. Biologically speaking.”

“That’s really strange,” Jeremy said. “Do you have a lot of this stuff?”

He shook his head. “I’m not supposed to have this one, but it was a gift and the authorities didn’t argue with me. The cops somehow got me past customs.”

“What’s this stuff mean? It’s not writing.”

“They don’t write. But they make symbols. I’m not sure in my own head what the difference is, but the experts say it isn’t writing.”

“This is so strange,” Jeremy said. “What’s it mean?”

“Day and night. Rain and sun. Grain growing.” He became aware that rain and sun, day and night, were words like the feather, alien to Jeremy, with all they meant. Spacers didn’t say morning and evening. It was first shift, second shift. They didn’t say day and night. It was mainday, maindark, alterday, alterdark. And twilight was a time the lights dimmed and brightened again, mainday’s twilight, alterday’s dawn. Stationers were like that, too. But on Downbelow you rediscovered the lost words, the words humans had used to have, words that clicked into a spot in your soul and took rapid, satisfying hold.

Maybe that was why they had to bar humans from Downbelow, and let down only a privileged, special few who could agree not to pick up feathers or stones.

“The little stones,” he remembered to say, “water smoothed them. They tumble over one another in the bottom of Old River as the water flows, just rubbing against each other.” He took account of Jeremy’s literal interpretation of molting feathers, and remembered a question he’d asked of a senior staffer. “You don’t ever see them move. But when Old River floods, it tumbles them.”

Jeremy looked at him as if to see if that was a joke of any kind, and felt the smoothness of the stones. “I was going to ask how,” Jeremy said. “That’s so, so wild. I’m used to old rocks… but these must have been tumbling around a long time.”

“Rocks in space are older,” he said. “Water’s just pretty powerful. It carves out cliffs, changes course, floods fields. Gravity makes it fall from high places to low places and whatever’s in the way, it flows around it or over it.”

“How’s it get high in the first place?”

“Rain. Springs.” More miracle words to Jeremy. He didn’t think Jeremy knew what a spring was.

But Jeremy wanted to know things. That was what engaged him. Jeremy wanted to know. He could liken some things to what Jeremy did know: condensation on high dockside conduits. The big drops that hit you on the head when you were near the gantries.

“It’s just past monsoon, now,” he said, dazed to admit the unfelt time-flow that Jeremy took for granted “Hisa females will be pregnant, grain will be sprouting in the fields and in the frames. There’s a kind that only grows with its roots in mud. There’s a kind that only grows on dry land, in the open fields. We interfered to improve the yield, but the thinking now is that we shouldn’t have, that it’d be a lot better if we’d left the hisa alone and not had them working on the station or anything.”

Jeremy handed the stick back carefully. “Do you think so?” Maybe Jeremy heard the disbelief in his voice. Do you think so? Jeremy asked straight into his privately-held, his cherished heresy. None of the staffers had ever seen it. But Jeremy did. And deserved an answer he’d never give, in hearing of Pell authorities, who could bar him from the planet as dangerous.

“I think maybe they’d gain something from developing at their own pace.” The cautious apology to official policy. But he plunged ahead. “Or maybe they’d gain things from us we never thought of. Or they might die out without us. You know there aren’t that many sites in the world where there are hisa. World population’s given to be, oh, maybe twenty million.”

“That’s a lot.”

“Not for a planet Not at all for a planet.”

Jeremy was quiet for a moment. “Dead-on that Earth’s got a lot.” Jeremy had been there, Jeremy had said so. The fabled and unreliable motherworld. Wellspring of everything they knew about planets. All the preconceptions, all the right and wrong perceptions.

“Yeah,” he said “That’s our model. That’s what we know in the universe. That’s all else we know and it’s a pretty small sample. Twenty million hisa on Downbelow. A lot fewer platytheres on Cyteen.”

“They’re not intelligent.”

“They don’t seem to be.” What he knew said that Cyteen’s platytheres had gotten too successful for their own environment, deforested vast tracts that then became prey to weather patterns. And human beings on Cyteen had determined the planet was more useful and more viable if they killed them all. Environmental scientists on Pell were aghast.

But nature sometimes killed itself. Not all life succeeded. Could life intervene to save life, when the end result would be extinction, or did nature know best?

He wasn’t sure. It was all human judgment. The hisa had watched the sky for as long as hisa remembered, from before humans left Earth. Waiting for something to happen from their clouded, starless sky. Was it a cultural dead end they’d reached?

“You know a lot of stuff,” Jeremy said.

“I’m two years short of a degree in Planetary Science. You know? It’s my life . It’s what’s important to me. And somebody aboard asked me why study planets.”

“Because you want to know!” Jeremy said, which did a lot to patch that young woman’s careless dismissal. “Because you want to know stuff. I do, anyway.”

“I don’t think what I know is real useful here.”

“You know science, don’t you?”

“A lot of life science.”

“Well, tell JR. I’ll bet he’d be interested. Life science is what keeps us breathing, case of what’s important, here. You probably ought to talk to Jake. He’s the bioneer.”

“Probably I should,” he said, “talk to Parton, that is.” Dealing with JR, he preferred to keep to a minimum. “Maybe I could do something besides laundry. ”

“Oh, everybody does laundry sooner or later,” Jeremy said. “Just the chief engineer sends all the junior engineers to do it, right along with maintenance, and the chief doesn’t unless he loses a bet. But you ’prentice to Jake, is what you do. Me, I’m off studies for the last couple of jumps because I’m watching you so you don’t turn green and die. Usually I’m on study tape. That’s where Vince goes after shift, That’s where Linda goes. You just do sims until there’s a rush on, and then they call you in, like me, I do beginner pilot sims and scan sims, because if I don’t make the cut when I’m big enough, you know, for the real test stuff, there’s got to be something for me to do. God, I really don’t want to do scan. I really hate it.” Jeremy was slapping his fist against his leg, that nervousness he got from vid-games; now Fletcher knew where it came from. “But even if I make Helm, I’ll have to sit Scan in a crisis. Same as Linda. She likes it, though. She thinks it’s great.”

“What’s Vince?” He had to know. The set wasn’t complete.

“Vince, he’s Legal. That’s what he wants to do, can you believe it? That and archive and files and library. It’s about the same. Records.”

Vince at a desk, doing painstaking work. A lawyer. A librarian. Their hothead wanted to keep books? The mind didn’t easily form that image. Plead in court? The judge would throw Vince in jail.

“I think you ought to talk to Jake, though,” Jeremy said.

“I’m sure they’ve got my records.” They don’t care, was in his mind. But also there was the glimmer of a use for himself. Not the use he wanted, but it was using something he knew and having contact with the systems on a ship that did technically interest him. A foam-steel planet, in those respects, recycling its atmosphere and doing so in systems he wanted to see.

“You want me to talk to Jake?” Jeremy asked.

“I’ll talk to him, sooner or later.” He tucked the stick back into the drawer, and shut it “Right now I guess it’s enough I don’t turn green and die.”

“Medical said let you go through maybe four, five jumps before you do anything like tape. The captains used to not let any of us do it. Used to make us learn with books. But the information just comes too fast, that’s what Paul said. Helm said if pilots could do tape-sims to keep their skills up then the rest of us weren’t going to go azi-fied on a calculus tape. I’m glad. Dead-on I’d be an azi if I had to learn calculus out of a book. You’d just see the blank behind the eyes…” Jeremy gave his rendition of an automaten. “Did you learn from books on Pell?”

“Tape, mostly. Lots of tape. Same thing. They’ve come round to thinking it’s all right. I brought some with me,—All right, I lied. I’ve got tapes. Some of the environmental stuff. My biochem.” Just the pretty ones, those first of all. The ones with pictures of home. His home. He didn’t think he could take them right now. It still hurt too much. “You can try one if you want.” Turning Jeremy into somebody he could really talk to about Downbelow was a bonus he hadn’t expected when he’d packed the tapes. But that seemed possible, and his spirits were higher than they had been since he’d boarded.

“Yeah,” Jeremy said. “Sure! Wild! Can I borrow one tonight?”

He opened the drawer, took out his tape case, took out a pretty one.

And hesitated. “It could be scary for you. I don’t know. It’s a planet. You feel the weather. Thunder and all. It’s a pretty good effect.”

“Oh, hell,” Jeremy said. “Can’t be that bad.” Jeremy took the tape and opened the wall panel at the side of his bunk, looking for pills.

“Take a quarter-dose, no more. This is stationer tape. Planetary tape. Lightning and reverse-curve horizons. If you climb the walls tonight it won’t be my fault.”

Jeremy grinned at him and shook out a pill. He split it. Offered the other half to him.

He opted for the biochem tape for his own reader. It wasn’t jump they faced, just a night’s sleep, and a night of no dreams but the ones the tape provided—a Downbelow tour for Jeremy and a night of life process chemistry for him.

He didn’t care that he was into Chad for a room cleaning. He settled down with the headset and the tape going and with the drug that flattened out your objections to information coursing through his bloodstream.

It was the first time he’d taken tape aboard. It was the first time he’d trusted the people he was with enough to take that drug that made you so helpless, so compliant, so ready to believe what you were told. You didn’t learn around strangers. You didn’t, in his own experience, do it anywhere but locked in your own private room, safe from outside suggestion, but he felt safe to try, finally, in Jeremy’s presence.

It meant a good night’s sleep, a night in which he was back in things he knew and terms he understood. You forgot little details if you didn’t use what you learned; tape could sharpen up what was getting hazy in your mind, and if he talked to Jake in engineering as Jeremy suggested, about getting into something that offered a little more headwork, he wanted to be sharp enough to impress Jake and not sound a fool if Jake asked him questions. This time through the old familiar tape he set his subconscious to wonder about things that a closed system like a ship’s lifesupport might find problematic, and he wondered what tapes the ship’s technical library might have that would let him brush up on specifics of the systems. The ship had a library. They might let him have tapes to study. If they trusted him , which had become an unexpected hurdle.

Talk to JR? Not damned likely.

Chapter 13

There’s a problem,” Bucklin put it, warning JR what was coming, and after that there was a junior staff meeting, a quiet and serial staff meeting, pursued down corridors, anywhere JR could find them. JR found Vince and Linda, among the first, in A deck main corridor, and made them late reporting to breakfast.

“What’s this with a Welcome-in?” he asked “I said, did I not, let him alone?”

There were frowns. There were no effective answers.

He found Connor topside, B deck, and said, “It’s off. No hazing. My orders.”

He found Sue and Nike in A deck lifesupport, and asked, “Whose damn idea was it in the first place?”

He didn’t get a satisfactory answer. What he got was, “He’s a problem. He’s a problem in everything, isn’t he?”

He found Chad, and said, “If he cleans your room, Chad, he just cleans it. You keep your hands off him or you and I are going to go a round.”

Chad wasn’t happy.

He went the whole route. Lyra and Wayne, Toby, and Ashley, all glum faces and unhappy attitudes.

And after he thought that he’d made the issue crystal clear, at mid-second shift he had a delegation approach him in the sim room, next to the bullet-car that reeked of the cold of the after holds. He was going in, not out, but he was still mentally hyped for the pilot-sims his career-track mandated—sims that didn’t have anything to do with Pell’s vid-game amusements. It was high-voltage activity that maintained his ability to track on high V emergencies, just as Helm had had to do when it met the Union carrier, and his state of mind at the moment was not optimal for intricate interpersonal politics. Bucklin had to know that.

It was Wayne and Connor, Toby, Chad and Ashley who pulled the ambush, and they’d done it in the cramped privacy of the core-access airlock, a small sealed room with a pressure door between it and the main A-deck corridor. It was only them, they could talk without senior crew in the middle of it, and Bucklin , damn him, had unexpectedly chosen to become their spokesman. JR found himself ready to blow, given just a little encouragement.

“The question is,” Bucklin said as JR stood with his hand on the call-button that would give him the sim-car and take him away from their bedeviling. “The question is, this is what we’ve always done. Omitting it says something.”

He dropped his hand from the button. Clearly he wasn’t going to solve this in two seconds. Clearly, like dealing with Union carriers, sometimes the situation tested not one’s speed in handling a matter, but one’s self-control.

“Always isn’t this time,” he said to the group. “The guy is not one of us, he didn’t grow up in our traditions, he doesn’t know what we’re up to, and we don’t communicate all that well with that stationer-trained brain of his.”

“It seems to me,” said Ashley, “that those are exactly the reasons for having a Welcome-in.”

“No,” he said, and drew a calm breath. “The answer is no . It’s an order.”

“We did it for Jeremy,” Wayne pointed out. Wayne, next to Bucklin and Lyra, was their levelest head. “It was important then. It made lot of difference.”

“And I’m telling you we can’t do it for Fletcher. For one thing, the Old Man would have the proverbial cat. For another, he’s a stationer .”

“That’s the problem, isn’t it, up and down the list?” Chad said. “He’s a stationer. He doesn’t give a damn about this ship. He walks up, does as he pleases in front of everybody at the bar and thumbs his nose at you, and all of us—and nobody ever called him on it.”

“I called him on it. Immediately.”

“Yes, and he walked off. He roughs up Vince, he doesn’t stay for gatherings… say hello to him and you get stared at.”

“Did you hear the word order , Chad? I order you to let this drop.”

“Yessir, we hear, but—”

“We don’t think a Welcome-in is as important as it used to be,” Toby said, all earnestness, “or what? Is this part of the Old Rules? I thought it was the Old Rules. I thought that was what we were always hanging on to. I thought it was important to do the traditions. We’re going to have babies on this ship. are we not going to welcome them in when they come up, or what?”

“I’m saying—” He faced a handful of juniors who’d survived all the War could throw at them. Who’d kept the traditions intact. Who hadn’t given up the principles, the history, the honor of the ship. And who could tell them that the practices of a Welcome-in, centuries old, were stupid, silly, ridiculous?

The junior captain, the officer in charge of the juniors, wasn’t even supposed to be involved in this, and traditionally speaking, hadn’t been and hadn’t sought it. He’d gotten involved at all, point of fact, because he’d given an order first not to do it in this case, and then to wait, and now they’d come back to him to argue for now rather than later, because his order was in their way. It was crew business and not his business, by centuries-old habit. There was a tradition in jeopardy here just in their having to confront him.

And more serious to the welfare of the ship, their unity, their way of defining who was who, their way of including someone new in the traditions—all that was threatened. His position, like Bucklin’s, was defined by the lofty track toward the captaincy, but theirs was a network of relations with each other that would define all of their lifetime of working together. And he was looking down on it all from officer-height and saying, It’s not that important—at a time when the crew as a whole was facing the greatest and most profound change in its mission since it had become, de facto, Mallory’s backup.

They were feeling robbed. Robbed of their war, their victory, their outcome. He understood that. None of them liked what they saw as being sent away from a conflict that had cost them heavily. And he saw, staring into that lineup of faces, and taking in the fact that they were all male, that there was also the men-women issue. Lyra and Linda, female, made a small but separate society: their children, when they chose to get them, from whomever they chose to get them, were the hope of the ship, the hope, the future of Finity’s End . Young men, and it was specifically the young men of the crew who’d come to him… they were the tradition-keepers, the teachers: men had their importance to a merchanter Family not in getting children, but in being Family, in bringing up their sisters’ and their cousins’ children. They were the guardians of tradition; and they were, potentially, men on a ship with a damaged tradition, a shattered ship’s company, too damn many dead Finity brothers with too little memory on the part of the outside as to who’d died and what heroic sacrifices they’d made away trom the witness of stationers and worlds. There were all too many small, funny, or touching stories that had died with this uncle or that cousin, stories of the ship’s finest hours that never would find their way into Finity ’s archive, or into the next generation.

The men of Finity’s End alone knew what they were. The ship hadn’t been able to leave Fletcher to the ordinary existence of a stationer, but they hadn’t brought him in, either. Only the men could do that.

They were right. And after giving a halfway yes, he’d delayed too long. He’d weakened. He’d already gotten himself on the gravity slope by agreeing it had to be done.

“I’m still saying wait ,” he said, trying to recover what authority his wavering had undermined. Unpleasant lesson and one he was determined to remember. “I’m saying—just—whenever you do it, go easy. He’s not a kid or a senior. He’s had all those several years of waking transactions Jeremy hasn’t had, and for all I can figure, his mind did something during those years besides learn algebra, all right? He’s not a ship kid. Give him some credit for the age he looks—the way I did, dammit, over the damn drink. I think he’s due that.”

“He looks like you and me,” Bucklin was quick to remind him. “When he hits Mariner dockside, nobody but us is going to know how old he is. And we’re responsible for him. ”

“I say he’s gained a little more maturity than Jeremy. You’re right he’s got a body that mixes with adults, not kids. A body that’s mostly done with its growing. He’s Jeremy with a body at its fastest and his nerves a lot more under control. It’s got to make a difference. He’s been dealing with adults as an adult on station. Jeremy hasn’t.”

“You’re not supposed to know about what goes on,” Chad said, “officially speaking. You don’t know about it.”

“I’m saying use your common sense!”

“That’s fine,” Wayne said, “and we agree, sir, but you still don’t know about it. You’re not supposed to have been this far involved with it. Let us. That’s what this is about. He’s not one of us yet. He doesn’t know us. We don’t know him.”

“Yeah,” he said reluctantly, “I still don’t know about it.”

They left. He stood there, wired for the sim, literally. And telling himself he shouldn’t interfere.