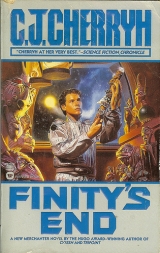

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

It was fantastical enough, JR judged. The juniors wouldn’t confuse it with reality. It wouldn’t give them nightmares—or encourage aggressive behavior.

It didn’t mean he and the senior-juniors weren’t going to slip down to Red or White Sector when the junior-juniors were safely in their rooms and see what the adult fare was like on the seamier side of Pell docks. The senior-juniors, his own lot, had crossed that line to anything-goes maturity in the seven years since they’d last made this port. They’d been out where combat was real, and they’d walked real corridors where surprises weren’t computer-spawned. They came back to their port of registry after seven station-measured years of hard living and real threats in deep space, and sat and sipped pink fruit drinks in a soft-bar with painted dinosaurs and garish dragons on the walls as the rest of their little band found their way out to the bar area and found their table.

Chad, Toby, Wayne, and Sue showed up, sweaty and flushed and admitting it actually had been a little wilder than they expected.

“Won’t hurt the juniors,” was JR’s pronouncement, between sips of his fruit juice. Sweet stuff. Almost sickeningly sweet. It brought back kid-days with a bitter edge of memory.

The whole trip brought back memories, a nightmare that wouldn’t quite come right, because the dead wouldn’t come back and enjoy the things they’d known and shared the last time they’d been at Pell. A lot of the crew was having trouble with that, ghosts, almost, the eye tricked, in a familiar venue, into believing one face was like another face,

Or remembering that you’d been at a theater, and finding your group several short of a momentary expectation, a memory, a remembrance of things past.

Ghosts, far more vivid than any computer sim… poignant and provoking dreams. But you had to let them go. At his young age, he knew that. He’d just expected a bit more…

Dignity,

Pell had been a grim, joyless place during the war, so the seniors said; he’d seen it make its docks a rowdy, neon-lit carnival in the years since. Now… now the place had dinosaurs, as if the place had finally, utterly, slipped its moorings to reality.

So the Old Man said they were going back to trading, making an honest living, the Old Man said, now that Mazian’s pirates had gone in retreat and seemed apt to nurse their wounds for some little time. At least for now, the shooting war was over.

So where did that leave them, a combat-trained crew, brightest and best and fiercest youth of the Alliance?

Testing out the facilities—desperate hard duty it was—that they were going to let the junior-juniors into. Babysitting.

Well, that was the reversion the Old Man had talked about in his general speech to the crew. They could have a real liberty this time, the Old Man had said, and the Old Rules were in effect again, rules that had never been in effect in JR’s entire life, and he was the seniormost junior, in charge of the younger juniors. The dino adventure was now the level of the judgment calls he made, a little chance to play, act like fools… or whatever the easy, soft station-bred population called it, when grown men sweated and outran imaginary dragons, while paying money for the privilege.

This was station life, not much different than, say, Sol, or Russell’s, or any other starstation built on the same pattern, the same design, down to the color-codes of its docks, an international language of design and function. Pell was richer, wilder, fatter and lazier. Pell partied on with post-War abandon and tried to forget its past, the memorial plaques here and there standing like the proverbial skeletons at the feast. On this site the station wall was breached …

This was Q sector…

People walked by the plaques, acting silly, wearing outlandish clothes, garish colors. People spent an amazing amount of money and effort on fashions that to his eye just looked odd. Station-born kids prowled the docks looking for trouble they sometimes found. Police were in evidence, doing nothing to restrain the spacers, who brought in money; a lot to restrain station juveniles, who JR understood were a major problem on Pell, so that they’d had to caution their own junior-juniors to carry ship’s ID at all times and guard it from pickpockets.

There was so much change in Pell. He couldn’t imagine the young fashioneers gave a damn for anything but their own bodies. His own generation was the borderline generation, the one that had seen the War to end all wars… and even at seventeen, eighteen ship-years, now, still a mere twenty-six as stations counted time, he saw the quickly grown station-brats taking so damn much for granted, despising money, but measuring everything by it

Hell, not only the station-brats were affected. Their own youngest were quirky, strange-minded, too fascinated by violence… even shorter of decent upbringing than his own neglected peers,—and that was going some.

Dean and Ashley showed up. Nike and Connor came next. The waiter, forewarned, was fast with the drinks, while they talked about the strangling plants effect and the swamp and the engineering.

“Effex Bag,” Bucklin said “Same one, I’ll bet you.” It was a full-body pocket you dealt with. The things fought back as hard as you could provoke them to fight, but a feed-back bag was self-limiting and you learned a fair lesson in morality, in JR’s estimation: at least it taught a good lesson about action and reaction, and the effects here were more sophisticated than the primitive jobs they’d met in their repair standdown at Bryant’s, a notable long time ashore. The quasi-dangers in any Effex Bag were all your own making. Hit it, and it hit back, Struggle and it gave it back to you. Go passive and you got a tame, boring ride,

“Pretty good jolt at the end,” Dean said “They drop you real-space.”

“Yeah,” Nike said “About a meter. Soft.”

“Junior-juniors’ll like this one” JR said, deciding he couldn’t take more of the pink juice. He listened to his team wondering about trying the Haunted Castle for another five credits.

Vid games and sims. Earth’s cultural tourism run amok.

You could experience a rock riot. Swing an axe in a Viking raid, never mind that they equipped the opposing Englishmen with Renaissance armor.

The reapplication of the pre-War Old Rules on Finity’s End had let them out without restrictions for the first time in three decades, after the rest of the universe had been war-free for close to twenty years, and this senior-junior, listening to his small command discuss castles and dinosaurs, had increasing misgivings about their sudden drop into civilian life. The fact was, he hadn’t had an unbridled fancy in his life and didn’t know what to permit and what to forbid, but after an education, both tape-fed, and with real books, that had taught him and his generation the difference between a dinosaur, a Viking and Henry Tudor, he felt a little embarrassed at his assignment. Foolish folly had become his job, his duty, his mandate from the Old Man. And here they were, about to loose Finity’s war-trained youngest on the establishment.

Under New Rules or Old Rules, however, they didn’t wear Finity insignia when they went to kid amusements or when they went bar-crawling, or doing anything else that involved play. It was a Rule that stood. Break it at your peril. Finity insignia, in a universe of slackening standards, sloppy procedures, almost-good instead of excellent, still stood for something. Finity personnel wouldn’t be seen falling on their ass in a carnival, not in uniform. But there was one in his sight at the moment, a junior cousin violating the no-uniforms rule. He indicated the cousin with a nod, and Bucklin looked.

“That’s in uniform,” Bucklin declared in surprise.

That was Jeremy, their absolute youngest: Jeremy, who eeled his small body among the tables of sugar-high youth, wearing his silver uniform and with the black patch on his sleeve.

He went for their table like a heat-seeking missile.

Business. JR revised his opinion and didn’t even begin a reprimand. Jeremy’s look was serious.

“They got Fletcher,” was Jeremy’s first breath as Jeremy ducked down next to them, “We got him. They signed a paper.”

“Cleared the case?” JR was, in the first breath, entirely astonished. And in the next, disturbed.

“Well, damn,” Bucklin said.

It was more than Bucklin should have said to a junior-junior. But Jeremy’s young face showed no more cheerful opinion.

“What terms?” JR asked. “Is there any word how? Or why?”

“Did he apply to us?” The Fletcher Neihart case had gone on most of his life. They’d never worked it out. Now with so many things changing, the Rules upending, the universe settling to a peace that eroded all sensible behavior, this changed.

“I don’t know what they agreed,” Jeremy said. “I just heard they signed the papers and he’s on the planet or something, but they’re going to get him up here and we’re taking him.”

How in hell? was the question that blanked other thinking.

They , the junior crew, were not only turned loose among dinosaurs—all of a sudden they had a station-born stranger on their hands.

“That all you know?” JR said

“Yes, sir, that’s all. I just came from the sleepover. Sorry about the patch. I’m getting out of here.”

“This place is on the list,” JR said meaning it was all right for junior-juniors, and Jeremy’s eyes flashed with delight that didn’t reckon higher problems.

“Yessir,” Jeremy said “Decadent!”

“Vanish,” JR suggested And should have added, Walk! but it was too late: Jeremy was gone at a higher speed than made an inconspicuous exit. Even the over-sugared teens in this place stared knowing who they were, and seeing that in this lax new world Finity crew played like fools and sat and drank with the rest of the human race.

Observers who had jobs besides games might have noticed too, and know that Finity’s seniormost juniors had just gotten a piece of not-too-good news on some matter. That could start rumors on the stock exchange. If it ricocheted to the Old Man, the junior crew captain would hear about it.

The junior crew, meanwhile, didn’t break out in complaints, just looked somberly at him—waiting for the word, the junior-official position from him, on a situation that had just suddenly cast a far more uncertain light not only on their liberty in this port, but on their whole way of working with one another.

“Well,” JR said to his crew, moderately and reasonably, he thought, and trying to put a cheerful face on the circumstances, “—this should be interesting.”

“He’s a stationer,” was the first thing out of Lyra’s mouth.

“He may be,” JR said, “but you heard the word. If it’s true, we’ve got him.” He tossed a money card at Bucklin and got up. “Handle the tab. I’ve got to talk to the Old Man.

Rain blasted down. The clean-suits were plastered to their bodies as they hurried down a scarcely existent path, and Fletcher’s breath came short. The light-headedness he suffered said he was needing to change a cylinder, but he didn’t want to stop for that, with the lightning ripping through the clouds and the rain making everything slippery. They were already going to be late getting back, and he knew their truancy was beyond hiding.

He had to get Bianca back safely. He had to think of what to say, what to do to protect himself and her reputation; all the while his breaths gave him less and less oxygen even to know where he was putting his feet.

His head was pounding. He slipped. Caught himself against a low limb and tried to slow his breathing so he could get something through the cylinders.

“What’s the matter?” Bianca wanted to know. “Are you out?”

“Yeah.” He managed breath enough to answer, but his head was still swimming. He had to change out. The rules said—they were posted everywhere—advise your partner if you felt yourself get light-headed: if you were alone, shoot off the locator beeper you weren’t supposed to use in anything but life and death emergency. But they weren’t to that point. If he hadn’t been a total fool. A hand against his thigh-pocket advised him he was all right, he’d replaced the last one—when? Just yesterday?

“Need one?” Bianca’s voice was anxious.

“Got my spares. Let’s just get there. Don’t want to be logged any later than we are.” He kept moving to push a little more out of the cylinders he was using: you could do that if you got your breathing down.

“They’re gone!” Bianca said, then, looking around, and for a second his muddled brain didn’t know what she was talking about. “I didn’t see them leave.”

He hadn’t seen Melody and Patch go, either. Desertion wasn’t like them. But downer brains grew distracted with the spring. Did, even on the station… and was this it? he asked himself. Was it the time they would go, and had they left him? Maybe for good? Or were they just scared of the storm?

The lightning flickered hazard above their heads… danger, danger, danger , a strobe light would say on station. It said the same here, to his jangled nerves. He walked, lightheaded and telling himself he could make it further without stopping for a change—at least get them past the place where the trail looped near the river: that was what scared him, the chance of being stranded or having to wade. The tapes they’d had to watch on what the monsoon rains did when they fell chased images through his head, of washouts, trees toppling, the land whited out in rain.

Melody and Patch, he said to himself, must have sought shelter. There were always old burrows on the hillsides, and hisa grew afraid when the light faded. When Great Sun waned, there was no place for His children but inside, safe and warm and dry.

Good advice for humans, too, but they daren’t bed down anywhere but at the Base. He heard his heart beating a cadence in his ears as, through the last edge of the woods and the gray haze of rain, he saw the fields and the frames.

“We’ll make it,” he gasped

“But we’re late,” Bianca moaned. “Oh, God , we’re late!”

They were fools. And Bianca was right, they were going to catch it, catch it, catch it.

They reached where he’d been working—close to there, at any rate. He’d left a power saw up on the ridge, and if he didn’t have it when he checked in, he’d catch hell for that, too.

“Keep going!” he said to her. “I’ll catch up!” And when she started to protest he shouted at her: “I left my saw up there. I’ll catch up!”

She believed him, but she was arguing about the failing cylinder he’d complained of, about how he was already short, and he couldn’t run. “Change cylinders!” she said, and held onto him until he agreed and got his single spare out of his pocket.

Rain was pouring down on them and you weren’t ever supposed to get the cylinders wet, even if they had a protective shell. You got them out of the paper they were in and all you had to do was shove them in, but you had to keep your head and eject one and replace one, and then go for the other one. You weren’t supposed to run out of both cylinders at the same time, but he realized he’d been close to it, and light-headed, as witness, he thought, the quality of his decisions of the last few minutes.

Bianca tried to help his fumbling fingers, and opened the packet on one cylinder of little beads. She was stripping it fast to hand it to him and he ejected one of his.

Her tug on the packet spun the cylinder out of her wet hands and she cried out in dismay. It landed in water, with its end open. Ruined. In the mask, it would have survived a dunking. Not outside it.

And he was on one depleted cylinder, with his head spinning.

“All right, all right,” he tried to tell her.

“I’ve got mine,” she said, and got out one of her spares, and opened it while he sucked in hard and held his breaths quiet, waiting for her to get it right, this time, and give him air enough to breathe.

She got it unwrapped and to his hand this time. Shielding the end from the rain, he shoved it in, then drew fast, quick breaths to get the chemistry started.

Then the slow seep of rational thought into his brain told him first that it was working, and second, that they’d had a close call.

He let her give him the second cylinder, then: they still had one in reserve, hers. You could lend a cylinder back and forth if bad came to worse, but you never let both go out together.

He was all right and he’d cut it damned close.

“Fletcher?” Bianca said. “I’m going with you. We’re down to three. Don’t argue with me!”

“It’s all right, it’s all right.” He pocketed the wrappers: you had to turn them in to get new ones, or you filled out forms forever and they charged you with trashing. Same with the ruined cylinder. He was going to hear about it. It was going on his record.

“Just leave the saw,” she pleaded with him. “Say we were scared of the lightning.”

It was half a bright idea.

“We were late because of the cylinders,” he said, with a better one, “and we can still pick up the saw. Come on.”

She picked up on the idea, willingly. She went with him down the side of one huge frame to where he’d been cutting brush. They couldn’t get wetter. The lightning hadn’t gotten worse.

It was maybe ten minutes along the curve of a hill to where he’d left the saw in the fork of a tree. Safe, Waterproof.

But it wasn’t there.

For a moment, he doubted it was the right tree. He stood a moment in confusion, concluding that someone had gotten it, that it might have been—God help him—a curious downer—a thought that scared him. But it most likely was Sandy Galbraith, who’d been working not in sight of him, but at least knowing where he was.

If it was Sandy checking on him and if she’d found the saw but not him, she’d have been in a bad position of having to turn him in or having to explain why she had his equipment.

If she’d been half smart and not a damn prig, she’d have left the saw where it was and pretended she didn’t see anything unless she needed to remember.

Damn.

“Sandy probably got it,” he said, and that meant they were later and he had to come up with a story for the missing saw, too.

He’d gone to look for Bianca because of the rain coming, that was it.

“Look,” he said, as lightning whitened the brush, and they started slogging back the ten minute walk they’d come out of the way already. “I’m going to catch hell if somebody turned it in. What happened was, I knew you were by the river, and I was worried about the rain, and I ran down there to warn you, and that was why I left the saw.”

She was keeping up with him, walking hard, and didn’t answer. Maybe she didn’t like lying to the authorities. Maybe she was mad at him. She had a right to be.

“I know, I know,” he said. “I don’t want to lie, either, but I didn’t plan on the rainstorm, all right?” That she didn’t leap at the chance to defend him made him—not mad. Upset—because of the cascade of stupid things that had gone wrong.

Maybe he’d spent too much time with psychs in his life, but he could say ‘displacement’ with the best psych that was out there: he and the psychs had talked a lot about his ‘displacement.’ And he was having a lot of displacement right now, to the extent that if he really, really had the chance to pound hell out of somebody, he would. He was upset, short of breath, and as they slogged through the mud washing from the sides of the frame, and on to the road, which was a boggy mess, he didn’t know whether Bianca was mad at him or not. They didn’t have any breath left to talk. They just walked, until they were on the approach to the domes.

“Remember what you’ve got to say,” he said on great, ragged breaths. “If we’ve got the same story they’ll have to believe us. I left the saw to go after you and I was running low on the cylinders and we were taking it slow coming back so we’d save the cylinders so as not to run without a spare apiece.” They didn’t let them have any more than a spare set, but they were supposed to come back to the Base immediately if they were out without a spare. You were supposed to stick with your buddy so you could share a set if you had to. And not run. That part was important. That was the core of the excuse. “Got it?”

“Yes,” she said, out of breath.

The domes were close now, veiled in rain as the doors of the admin dome opened and a figure came out toward them.

Deep trouble, he thought. Administration knew. It was his fault.

JR stepped off the slow-moving ped-cab in front of number 5 Blue Dock, where a gantry with skeins of lines and a lighted ship-status sign was the only evidence of Finity’s presence the other side of the station wall. Customs was on duty, a single bored agent at a lonely kiosk who looked up as he came through the gate. Customs manned such a kiosk in front of limp rope lines at every ship at dock—and, at Pell, ignored most everything on a crew activity level.

The flash of a passport at the stand, a quick match of fingerprints on a plate, and he made his way up the ramp, past the stationside airlock and into the yellow ribbed gullet of the short access tube. The airlock inside took a fast assessment of the pressure gradient between ship and station and, as it cycled, flashed numbers and the current sparse gossip at him …I’m moving to the DarkStar—Cynthia D . Someone had met up with someone interesting, gone off and advised the duty staff of the fact she wasn’t where she’d first checked in.

Finity personnel didn’t do much of that.

Hadn’t done much of it. Correction.

It was in a lingering sense of uncertainty that he walked out of the airlock and into the lower corridor of his ship at dock. The Ops office door was open, casting light onto the tiles outside, a handful of seniors maintaining the systems that stayed live during dock, and whatever was under test at the moment. JR put his head in, asked the Old Man’s whereabouts.

The senior captain was aboard, was in his office, was at work, would see him.

He went ahead, down the short corridor past Cargo and by the lift into Administrative. Senior captains’ territory. Offices, and the four captains’ residences in B deck, directly above, all arranged to be useable during dock, when the passenger ring was locked down.

It was a moment for serious second thoughts, even with honest administrative business on his mind. Business he’d gotten by scuttlebutt, not official channels.

He was damned mad. He realized that about the time he reached the point of no retreat. He was just damned mad. He knew James Robert Sr. would have policy as well as personal reasons for what he’d done. He even knew in large part what the policy decisions were.

But the result had landed on his section.

He signaled his presence, walked in at the invitation to do so, stood at easy attention until the Old Man switched off a bank of displays in the dimly lit office and acknowledged him by powering his chair to face him.

“Sir,” JR said. “I’ve just heard that Fletcher’s coming in. Is that official?”

The light came from the side of the Old Man’s face, from displays still lit. The expression time had set on that countenance gave nothing away. The Old Man’s eyes were the reliable giveaway, dark, and alive, and going through at least several thoughts before the sere, thin lips expressed any single opinion.

“Is it on the station news,” James Robert asked, “or how did we reach this conclusion?”

“Sir, it came on two feet and I came over here stat.”

“Sit down.”

JR settled gingerly into a vacant console chair.

The silence continued a moment.

“So,” James Robert said, “I gather this provokes concern. Or what is your concern about it?”

“He’s in my command.” He picked every word carefully. “I think I should be concerned.”

“In what way?”

“That we may have difficulty assigning him.”

“Is that your concern?”

“The integrity of my command is a concern. So I came here to find out the particulars of the situation before I get questions.”

Again the long silence, in which he had time to measure his concerns against James Robert’s concerns, and James Robert’s demands against him and a very small rank of juniors.

James Robert’s grand-nephew, Fletcher was. So was he.

James Robert’s unfinished business, Fletcher was. James Robert said there were new rules, the new Old Manual they’d been handed, and about which the junior crew was already putting heads together and wondering.

“The particulars are,” James Robert said, “that a member of this crew will join us at board call. He’ll have the same duties as any new junior, insofar as you can find him suitable training. And yes, you are responsible for him. On this voyage, with the press of other duties, I have no time to be a shepherd or a counselor to anyone. In a certain measure, I shouldn’t be. He’s not more special than the rest of you. And you’re in charge.”

“Yes, sir.” Same duties as a new junior. A stationer had no skills. His crew, already unsettled by a change in the Rules, was now to be unsettled by the news. “I’ll do what I can, sir.”

“He’s not a stationer,” James Robert said directly and with, JR was sure, full knowledge what the complaints would be. “This ship has lost a generation, Jamie. We have nothing from those years. We’ve lost too many. I considered whether we dared leave him—and no, I will not leave one of our own to another round with a stationer judicial system. We had the chance, perhaps one chance, a favor owed. I collected. We are also out from under the 14.5 million credit claim for a Pell station-share.”

“Yes, sir.” Clearly things had gone on beyond his comprehension. He didn’t know what kind of an agreement might have hammered his cousin loose from Pell’s courts. He understood that, along with all other Rules, the situation with Pell might have changed.

“So how far has the rumor spread?” James Robert asked him.

On Jeremy’s two feet? Counting the conspicuous dress? “I think the rumor is traveling, sir, at least among the crew. It came to me and I came here. Others might know by now. I’d be surprised if they didn’t.”

“Jeremy.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Let a crew liberty without a five-hour check-in and they think the universe has changed. Drunken on the docks, I take it, when this news met you.”

“No, sir. Fruit juice in a vid parlor.”

The Old Man could laugh. It started as a disturbance in the lines near his eyes and traveled slowly to the edges of the mouth. Just the edges. And faded again.

“Life and death, junior captain. Ultimately all decisions are life and death. It’s on your watch. Do you have any objections? Say them now.”

“Yes, sir,” he said somberly. “I understand that it’s on my watch.”

“The generations were broken,” James Robert said. “From my generation to yours there was birth and death. There was a continuity—and it’s broken. I want that restored , Jamie.”

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“You still haven’t a chart, have you?”

“Sir?”

“You’re in deep space without a chart. We didn’t entirely get you home.”

He understood that the Old Man was speaking figuratively, this business about charts, about deep space, expressions which might have been current in the Old Man’s youth, a century and more ago.

“Too much war,” James Robert said. The man who, himself, had begun the War, talked about charts and coming home. About charts for a new situation, JR guessed. But home? Where was that, except the ship?

The Old Man got up and he got up. Then the Old Man, still taller than most of them, set his hand on his shoulder, a touch he hadn’t felt since he was, what?

Ten. The day his mother had died—along with half of Finity’s crew.

“Too many dead,” the Old Man said. “You’ll not crew this ship with hire-ons when you command her. You’ll run short-handed, you’ll marry spacers in, but you’ll never let hire-ons sit station on this ship, hear me, Jamie?”

The Old Man’s grip was still hard. There was still fire in him. He still could send that fire into what he touched. It trembled through his nerves. “Yes, sir,” he said faintly, intimately, as the Old Man dealt with him.

“I’ve given you one of your cousins back. I’ve agreed to Quen’s damned ship-building. It was time to agree. It’s time to do different things. Time for you, too. You’re young yet. You—and this lost cousin of ours—will see things and make choices far beyond my century and a half.”

“Yes, sir.” He didn’t know what the Old Man was aiming at with this talk of crewing the ship, and building ships for Quen of Pell. But not understanding James Robert was nothing new. Even Madison failed to know what was on the Old Man’s mind, sometimes, and damned sure their enemies had misjudged what James Robert would do next, or what his resources were.

“Making peace,” the Old Man said, “isn’t signing treaties. It’s getting on with life. It’s making things work , and not finding excuses for living in the past. Time to get on with life, Jamie.”

The Old Man asked, and the crew performed. It wasn’t love. It was Family. And Family forever included that gaping, aching blank where a generation had failed to be born and half of them who were born had died. It was the Old Man reaching out across those years of conflict and training for conflict—and saying to their generation, Make peace.

Make peace.

God, with what? With a station obsessed with games and dinosaurs? With Union more unpredictable as an ally than it had been as an enemy?

That prospect seemed suddenly terrifying in its unknowns, more so than the War that had grown familiar as an old suit of clothes. The universe, like his whole generation, was in fragments and ruin.

And the Old Man said, without saying a word, Do this new thing, Jamie. Go into this peace and do something different than you’ve ever imagined in the day you command .

He was back on that cliff again. Jump off, was James Robert’s clear advice. Try something different than he’d ever known.

And to start the process, of all chancy gifts, the Old Man gave him the new Old Rules and a rescued cousin who wasn’t any damn use to the ship except the bare fact that getting Fletcher back closed books, saved the Name, prevented another disaster in Pell courts.

And maybe redeemed a promise, a loose end the Old Man had left hanging. Francesca herself had shattered, lost herself in a fantasy of drugs. But she’d kept her kid alive and under her guardianship, always believing, by that one act, that they’d come back.