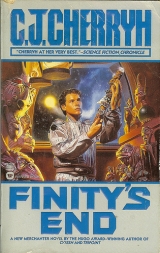

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 30 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

She’d known. Yes, she’d known. As the Old Man of Finity’s End had known—things he’d never imagined as the condition of his universe.

“ All right, cousins ,” the intercom said. “ You can eat what you stowed before jump or you can venture out for a stretch. Both mess halls will be in service in ten minutes, so it’s fruit bars and nutri-packs solo or it’s one of those hurry-up dinners which your bridge crew will be very grateful to receive. Remember, there is still no laundry .”

Jeremy came out of the shower smelling of soap and bringing a puff of steam with him. It was far better air now. The fans were making a difference.

Downbelow slipped away in the immediacy of clean water and warmth and soap. Fletcher stripped clothes and went, chased through his mind by images of woods and water, the memory of air that wouldn’t come, but the shower was safe and clean and Jeremy was his talisman against nightmares and loss.

“Sir?” JR found the Old Man’s cabin dimly lighted as he brought the tray in, heard the noise of the shower, in the separate full bath Finity ’s senior crew enjoyed. He ordered the lights up, set the meal in the dining alcove, and took the moment to make the stripped bed with the sheets set by and waiting.

The Old Man did such things himself. The senior-juniors habitually ran errands, down to laundry, down to the med station, and back, for all the bridge crew, whose time was more valuable to the ship; but the senior crew usually did their own bed-making and food-getting if they were at all free to do so.

In the same way the Old Man rarely ordered a meal in his quarters. He was always fast on the recovery, always in his office before the galley could get that organized.

Not this time. Not with the stress of double-jumping in and short sleep throughout their stay at Voyager. He felt the strain himself, in aches and pains. Mineral depletion. Jeff had probably dumped supplement in the fruit juice, as much as wouldn’t hit the gut like a body blow.

The shower cut off. JR poured the coffee. In a few more moments the bath door opened and the senior captain walked out, barefoot, in trousers and turtleneck sweater, in a gust of moist, soapy air.

“Good morning, sir.” JR pulled the chair back as James Robert stepped into the scuffs he wore about his quarters, disreputable, but doubtless comfortable. A click of a remote brought the screen on the wall live, and showed them a selection of screens from the bridge.

They were at the jump-point intermediate between Voyager and Esperance, a small lump of nothing-much that radiated hardly at all. If there’d been any other mass in two lights distance, the point would have been tricky to use… dangerous. But there was nothing else out here, and it drew a ship down like a far larger mass.

Systems showed optimal. They were going to jump out on schedule. JR remarked on nothing that was ordinary: it annoyed the Old Man to listen to chatter in the morning, or after jumps. He simply stood ready to slide the chair in as the Old Man sat down.

He looked up. The captain had stopped. Cold. Staring off into nowhere with a sudden looseness in his body that said this was a man in distress.

JR moved, bumping past the chair, seized the Old Man’s flaccid arm, steered him immediately to the seat at the table.

The Old Man got a breath and laid a shaking hand on the table,

“I’ll get Charlie,” JR began.

“No!” the Old Man said, the voice that had given him orders all his life, and it was hard to disregard it.

“You should have Charlie,” JR said “Just to look—”

“Charlie has looked,” the Old Man said. “Medicine cabinet, there in the bunk edge. Pill case.”

He left the Old Man to get into the medicine compartment, hauled out a small pharmacy worth of pill bottles he’d by no means guessed, and brought them back to the table. The Old Man indicated the bottle he wanted, and JR opened it. The Old Man took the pill and washed it down with fruit juice.

“Rejuv’s going,” the Old Man said then. “Charlie knows.”

It was a death sentence. A long-postponed one. JR sank down into the other chair, feeling it like a blow to the gut.

“Does Madison know?”

“All of them.” The Old Man was still having trouble talking, and JR kept his questions quiet, just sat there. The realization hit him so suddenly he’d felt the bottom drop out from under him… this was what the Old Man had meant at dinner that night back at Voyager. This was why it disturbed Madison: that he was saying it in public, for others to hear, not the part about the peace, but the part about finishing . The captain– the captain, among all other captains Finity had known, was arranging all his priorities, the disposition of his power, the disposition of his enemy, all those things… leading in a specific direction that left his successors no problem but Mazian. That was why the Old Man had said that peculiar thing about needing Mazian.

No, the Old Man hadn’t quarreled with Mallory and then left in some decision to pursue a different direction.

The Old Man had this one, devastatingly important chance to wield the power he’d spent a protracted lifetime building.

Secure the peace. Accomplish it. And look no further into human existence. The final wall was in front of him. The point past which never.

“Shall I call Madison, sir?” he asked the Old Man.

“Why?” the Old Man challenged him sharply. And then directly to him, to his state of mind: “Worried?”

The Old Man never liked soft answers. Least of all now. JR sensed as much and looked him in the eye. “Not for the ship, sir. You’d never risk her. But Charlie’s going to be mad as hell if I don’t tell him.”

The Old Man heard that, added it up—the flick of the eyes said that much—and took a sip of coffee. “I’ll thank you to keep Charlie at bay. I’ve taken to bed for the duration of the voyage. I plan to get to Esperance.”

“I’m grateful to know that, sir.”

“Precaution,” the Old Man said.

“Yes, sir.”

“You don’t believe it for a minute, do you?”

“I’m concerned.”

“And have you been discussing this concern in mess, or what?”

“I haven’t. You put one over on me, sir. Completely. I never figured this one.”

“Smart lad,” the Old Man said. “You always were.” He lifted the lid on the breakfast. Eggs and ham. Bridge crew got the attention from the cookstaff on short time schedules. So did the captain. So did the senior-seniors, for their health’s sake.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “Thank you. I try to be. I suggest you eat all of it and take the vitamins. My shoulders are popping. I’d hate to imagine yours.”

“The insufferable smugness of youth.” James Robert looked up at him. The parchment character of his skin was more pronounced. When rejuv failed, it failed rapidly, catastrophically. Skin lost its elasticity. The endocrine system began to suffer wild surges, in some cases making the emotions spiral out of control. There might be delusions. Living a heartbeat away from the succession, JR had studied the symptoms, and dreaded them, in a man on whose emotional stability, on whose sanity , so very much depended.

“Waiting,” the Old Man said, “for me to fall apart.”

“No, sir. Sitting here, wondering if you were going to want hot sauce. They didn’t put it on the tray.”

The Old Man shot him a look. The spark was back in his eye, hard and brilliant.

“You’ll do fine,” the Old Man said. “You’ll do fine, Jamie.”

“I hope to, sir, some years from now, if you’ll kindly take the vitamins.”

“In my good time,” the Old Man said in a surly tone. “God. Where’s respect?”

“For the living, sir. Take both packets.”

“Out. Out! You’re worse than Madison.”

“I hope so, sir.” He saw what reassured him, the vital sparkle in the eyes, the lift in the voice. Adrenaline was up. “I’d suggest you leave the transit to jump to Alan and Francie. Sir.”

“Jamie, get your insufferable youth back to work. I’ll be at Esperance. I’m not turning a hand on this run until I have to.”

“Yes, sir,” he said, glad of the rally—and heartsick with what he’d learned.

“Out. Tell Madison he’s got the entry duty. With first shift.”

And not at all happy.

“I’m moving everybody up,” the Old Man said with perfect calm. “I’m retiring after this next run. You’re to take Francie’s post. Madison will take mine.”

“Sir…”

“I think I’m due a retirement. At a hundred forty-nine or whatever, I’m due that. I’ll handle negotiations. Administrative passes to the next in line. Filling out forms, signing orders. That’s all going to be Madison’s, Jamie-lad. As you’ll be junior-most of the captains. And welcome to it. I’m posting you. At Esperance.”

The Old Man had surprised him many a time. Never like this.

“I’m not ready for this!”

The Old Man had a sip of coffee. And gave a weak laugh, “Oh, none of us are, Jamie. It’s vanity, really, my hanging on, waiting for an arbitrary number, that hundred and fifty. It’s silliness. I’m getting tired, I’m not doing my job on all fronts, I’m delegating to Madison as is: he’ll do the nasty administrative things and I do what I do best, at the conference table. Senior diplomat. I rather like that title. Don’t you think?”

“I’ll follow orders, sir.”

“Good thing. Fourth captain had damned well better. Meanwhile you’ve things to clean up before you trade in A deck.”

Fletcher. The theft. All of that. And for the first time in their lives he’d be separated from Bucklin, who’d be in charge of the juniors until Madison himself retired. He’d be taking over fourth shift, dealing with seniors who’d seen their competent, life-long captain bumped to third.

He felt as if someone had opened fire on him, and there was nothing to do but absorb the hits.

“Well?” the Old Man said

“Yes, sir. I’m thinking I’ve got mop-up to do. A lot of it.”

“Better talk to Francie. You’ll be going alterday shift, when ops is in question. Better talk to Vickie, too.” That was Helm 4. “You’ve shadowed Francie often enough.”

At the slaved command board—at least five hundred hours, specifically with Francie. During ship movement, maybe a hundred. He had no question of his preparation in terms of ship’s ops. In terms of his preparation in basic good sense he had serious doubts.

“Yes, sir,” he said.

“Jamie,” the Old Man said.

“Yes, sir?”

“The plus is… I get to see my succession at work. I get to know it will do all right. There’s no greater gift you can give me than to step in and do well. Fourth shift will do Esperance system entry. You’ll sub for Francie on this jump. We’ll hold the formalities after we’ve done our work there. King George can wait for his party. We’ll have occasion for our own celebration if we pull this off. We’ll be posting a new captain.”

Breath and movement absolutely failed him for a moment. He had no words, in the moment after that, except, quietly: “Yes, sir.”

One hour, thirty-six minutes remaining, when Fletcher stood showered and dressed; and the prospect just of opening the cabin door and taking a fast walk around the corridor was delirious freedom. Jeremy was eager for it; he was; and they joined the general flow of cousins from A deck ops on their way to a hot pick-up meal and just the chance to stretch legs and work the kinks out of backs grown too used to lying in the bunk. They fell in with some of the cousins from cargo and a set from downside ops, all the way around to the almost unimaginably intense smells from the galley.

“I could eat the tables,” a cousin said as they joined the fast-moving line. Jeremy had a fruit bar with him. He was that desperate. Everyone’s eyes were shadowed, faces hollowed, older cousins’ skin showed wrinkles it didn’t ordinarily show. Everyone smelled of strong soap and had hair still damp.

Two choices, cheese loaf with sauce or souffle. They’d helped make the souffle the other side of Voyager and Fletcher decided to take a chance on that; Jeremy opted for the same, and they settled down in the mess hall for the pure pleasure of sitting in a chair. Vince and Linda joined them, having started from the mess hall door just when they’d sat down, and Jeremy nabbed extra desserts. Seats were at a premium. The mess hall couldn’t seat all of A deck at once. They wolfed down the second desserts, picked up, cleaned up, surrendered the seats to incoming cousins, and headed out and down the way they’d come.

“Can I borrow your fish tape?” Jeremy asked Linda as they walked.

“I thought you bought one,” Linda said.

“I put it back,” Jeremy said, and Fletcher thought that was odd: he thought he recalled Jeremy paying for it at the Aquarium gift shop. Jeremy had bought some tapes and a book, and he’d have sworn—

He saw trouble coming. Chad, and Sue, and Connor, from down the curve.

“Don’t say anything,” he said to his three juniors. “They’re out for trouble. Let them say anything they want.”

“They’re jerks,” Vince said.

The group approached, Sue passed, Chad passed—they were going to use their heads, Fletcher thought, and keep their mouths shut.

Then Connor shoved him, and he didn’t think. He elbowed back and spun around on his guard, facing Chad.

“You turn us in?” Chad asked. “You get us confined to quarters?”

“Wasn’t just you,” Fletcher retorted, and reminded himself he didn’t want this confrontation, and that Chad might be the leader and the appointed fighter in the group, but he didn’t conclude any longer that Chad was entirely the instigator. “We all got the order. You and I need to talk.” A cousin with her hands full needed by and they shifted closer together to let her by. Jeremy took the chance to get in the middle and to push at Fletcher’s arm.

“Fletcher. Come on. We’re still in yellow. They’ll lock us down for the next three years if you two fight, come on, cut it out.”

“Got your defender, do you?” Connor said, and shoved him a second time.

“Cut it!” Jeremy said, and Fletcher reached out and hauled him aside, firmly, without even feeling the effort or breaking eye contact with Chad.

“You and I,” Fletcher said, “have something to talk about.”

“I’m not interested in talk,” Chad said. “I’ll tell you exactly how it was. You came on board late, you didn’t like the scut jobs, you didn’t like taking orders, and you found a way to make trouble. For all we know, there never was any hisa stick.”

“Was, too!” Jeremy said. “I saw it.”

“All right,” Chad said. “There was. Doesn’t make any difference. Fletcher knows where it is. Fletcher always knew, because he put it there, and he’s going to bring down hell on our heads and be the offended party, and we give up our rec hours running around in the cold while he sits back and laughs.”

“That isn’t the way it is,” Fletcher said. “I don’t know who did it. That’s your problem. But I didn’t choose it.” Another couple of cousins wanted by, and then a third, fourth and fifth from the other direction. “We’re blocking traffic.”

“Yeah, run and hide,” Sue said. “Stationer boy’s too good to go search the skin, and get out in the cold…”

“You shut up!” Vince said, and kicked Connor. Connor lunged and Fletcher intercepted. “Let him alone,” Fletcher said.

And Linda kicked Connor. Hard.

Connor shoved to get free. And Chad shoved Connor aside, effortless as moving a door.

“I say you’re a liar,” Chad said, and Fletcher swung Jeremy and Linda out of range, mad and getting madder.

“Break it up!” an outside voice said. “You!”

“Fletcher!” Jeremy yelled, and he didn’t know why it was up to him to stop it: Chad took a swing at him, he blocked it, and got a blow in that thumped Chad into the far wall. Chad came off it at him, and Linda was yelling, Vince was. He’d stopped hearing what they were saying, until he heard Jeremy yelling at him, and until Jeremy was right in the middle of it, in danger of getting hurt.

“Chad didn’t do it!” Jeremy shouted, clinging to him, dragging at his arm with all his weight. “Chad didn’t do it, Fletcher! I did it!”

He stopped. Jeremy was still pulling at him. Bucklin had Chad backed off. It was only then that he realized it was JR who had pulled him back. And that Jeremy, all but in tears, was trying to tell him what didn’t make sense.

“What did you say?” JR asked Jeremy.

“I said I did it. I took it .”

“That’s not the truth,” Fletcher said. Jeremy was trying to divert them from a fight. Jeremy was scared of JR, was his immediate conclusion.

“It is the truth!” Jeremy cried, in what was becoming a crowd of cousins, young and old, in the corridor, all gathering around them. “ I stole it, Fletcher, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean it.”

“What did you mean?” JR asked; and Jeremy stammered out,

“I just took it. I was afraid they were going to do it, so I did it.”

“You’re serious.”

“I was just going to keep it safe, Fletcher. I was. I took it onto Mariner because I thought they were going to mess the cabin and they’d find it and something would happen to it, but somebody broke into my room in the sleepover and they got all my stuff, Fletcher!”

Everything made sense. The aquarium tape Jeremy turned out not to have. The music tapes. The last-minute dash to the dockside stores. The thief had made off with every purchase Jeremy had made at Mariner, Jeremy had broken records getting back to their cabin to create the scene he’d walked in on.

But he wasn’t sure yet he’d heard all the truth. Fletcher’s heart was pounding, from the fight, from Jeremy’s confession, from the witness of everyone around them. Silence had fallen in the corridor. And JR’s hold on him let up, JR seeming to sense that he had no immediate inclination to go for Chad, who hadn’t, after all, been at fault. Not, at least, in the theft.

“God,” Vince said, “that was really stupid , Jeremy!”

Jeremy didn’t say a thing.

“Somebody took it from your room in the Pioneer,” JR said.

“Yes, sir,” Jeremy said faintly.

“And why didn’t you own up to it?”

Jeremy had no answer for that one. He just stood there as if he wished he were anywhere else. And Fletcher believed it finally. The one person he’d trusted implicitly. The one whose word he’d have taken above all others.

Jeremy was a kid, when all was said and done, just a kid. He’d failed like a kid, just not facing what he’d done until it went way too far.

“Let him be,” Fletcher said with a bitter lump in his throat. “It’s lost. It doesn’t matter. Jeremy and I can work it out.”

“This ship has a schedule,” JR said. “And it’s no longer on my hands. Bucklin, you call it. It’s your decision.”

“Fletcher,” Bucklin said. “Jeremy? You want a change of quarters? Or are you going to work this out? I’m not having you hitting the kid.”

Anger said leave. Get out. Be alone. Alone was safe. Alone was always preferable.

But there was jump coming, and the loneliness of a single room, and a kid who’d—aside from a failure to come out with the truth—just failed to be an adult, that was all. The kid was just a kid, and expecting more than that, hell, he couldn’t expect it of himself.

He just felt lonely, was all. Hard-used, and now in the wrong with Chad and the rest, and cut off from his own age and in with kids who were, after all, just kids, who now were mad at Jeremy.

“I’ll keep him,” he said to Bucklin. “We’ll work it out.”

Lay too much on a kid’s shoulders? It was his mistake, not Jeremy’s, when it came down to it: it was all his mistake, and he was sorry to lose what he’d rather have kept, in the hisa artifact, but the greater loss was his faith in Jeremy.

“You don’t hit him,” Bucklin said.

“I have no such intention,” he said, and meant it, unequivocally. He knew where else things were set upside down, and where he’d gotten in wrong with people: he looked at Chad, said a grudging, “Sorry,” because someone once in his half dozen families had pounded basic fairness into his head. The mistake was his, that was all. It wasn’t Jeremy who’d picked a fight with Chad.

Chad wasn’t mollified. He saw it in Chad’s frown, and knew it wasn’t that easily over.

“All right, get your minds on business,” Bucklin said. “A month the other side of this place maybe you’ll have cooled down and we can settle things. Honor of the ship, cousins. We’re family , before all else, faults, flaws, and stupid moves and all; and we’ve got jobs to do.”

By now the crowd in the corridor was at least twenty onlookers. There were quiet murmurs, people excusing themselves past.

“We have”—Bucklin consulted his watch—“thirty-two minutes to take hold.”

JR. said nothing. Chad and his company exchanged dark glances. Fletcher ignored the looks and gathered up his own junior company, going on to their cabin, Vince and Linda trailing them. He tried all the while to think what he ought to say, or do, and didn’t find any quick fix. None at all.

“Just everybody calm down,” was all he could find to say when they reached the door of his and Jeremy’s quarters. “It’s all right. It’ll be all right We’ll talk about it when we get where we’re going.”

“We didn’t know about it!” Vince protested, and so did Linda.

“They didn’t,” Jeremy said

“It was a mistake,” he found himself saying, past all the bitterness he felt, a too-young bitterness of his own that he spotted rising up ready to fight the world. And that he was determined to sit on hard. “Figure it out. It’s not something that can’t be fixed. It’s just not going to happen in two happy words, here. I’m upset. Damn right I’m upset. Chad’s upset. Sue and Connor are upset and all the crew who froze their fingers and toes off trying to find what wasn’t on this ship in the first place are upset, and in the meantime I look like a fool. A handful of words could have solved this.”

“I’m sorry,” Jeremy said.

“About time.”

“He didn’t tell us,” Vince said.

“You let him and me settle it. Meanwhile we’ve got thirty minutes before we’ve got to be in bunks and safed down. We’re going to get to Esperance, we’re going to have our liberty if they don’t lock us down, and we’re all four of us going to go out on dockside and have a good time. We’re not going to remember the stick, except as something we’re not going to do again, and if we make mistakes we’re going to own up to them before they compound into a screwup that has us all in a mess. Do we agree on that?”

“Yessir.” It was almost in unison, from Jeremy, too.

Earnest kids. Kids trying to agree to what they, being kids, didn’t half understand had happened, except that Jeremy was wound tight with hurt and guilt, and if he could have gotten to anyone on the ship right this minute he thought he’d wish for no-nonsense Madelaine.

“To quarters,” he said. “Do right. Stay out of trouble. Give me one easy half hour. All right?”

“Yessir,” faintly, from Linda and Vince. He took Jeremy inside, and shut the door.

Jeremy got up on his bunk, squatting against the wall, arms tucked tight, staring back at him.

Jeremy stared, and he stared back, seeing in that tight-clenched jaw a self-protection he’d felt in his own gut, all too many times.

Puncture that self-sufficiency? He could. And he declined to.

“Bad mistake,” he said to Jeremy, short and sweet. “That’s all I’ve got to say right now.”

Jeremy ducked his head against his arms.

“Don’t sulk.”

Back went the head, so fast the hair flew. “I’m not sulking! I’m upset! You’re going at me like I meant some skuz to steal it!”

“Forget the stick! You don’t like Chad, right? You wanted me to beat up Chad, so I could look like a fool, and it’d all just go away if you kept quiet and you wouldn’t be at fault. That stinks , kid, that behavior stinks . You used me!”

“Did not!”

“Add it up and tell me I’m wrong!”

Lips were bitten white. “I didn’t want you to beat up Chad.”

“So what did you want?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, do better ! Do better. You know what you were supposed to have done.”

“Yeah.”

“So why didn’t you tell me the truth , for God’s sake?”

“Because I didn’t want you to leave!”

“How long did you think you were going to keep it up? Your whole life?”

“I don’t know!” Jeremy cried. “I just thought maybe later it wouldn’t matter.”

He let that thought sit in silence for a moment. “Didn’t work real well,” he said. “Did it?”

“Didn’t,” Jeremy muttered, head hanging. Jeremy swiped his hair back with both hands. “I was scared, all right? I thought you’d beat hell out of me.”

“Did I give you that impression? Did I ever give you that impression?”

Jeremy shook his head and didn’t look at him.

“I thought the story was you were having a good time. Best time in your life. Was that it? Just having such a great time we can’t be bothered with telling me the damn truth , is that the way things were?”

“I didn’t want to spoil it!” Jeremy’s voice broke, somewhere between twelve-year-old temper and tears. “I didn’t want to lose you, Fletcher. I didn’t want it to go bad, and I didn’t know how mad you’d be and I didn’t know you’d beat up on Chad, and I didn’t know they’d search the whole ship for it!”

Fletcher flung himself down to sit on the rumpled bed.

“I didn’t know,” Jeremy said in a small voice. “I just didn’t know.”

Fletcher let go a long breath, thinking of what he’d lost, what he’d thought, who it was now that he had to blame. The kid. A kid. A kid who’d latched onto him and who sat there now trying to keep the quiver out of his chin, trying to be tough and take the damage, and not to be, bottom line, destroyed by this, any more than by a dozen other rough knocks. He didn’t see the expression; he felt it from inside, he dredged it up from memory, he felt it swell up in his chest so that he didn’t know whether he was, himself, the kid that was robbed or the kid on the outs with Vince, and Linda, and him, and just about everyone of his acquaintance.

Jeremy couldn’t change families. They couldn’t get tired of him and send him back for the new, nicer kid.

Jeremy couldn’t run away. He shared the same quarters, and Jeremy was always on the ship, always would be.

The history Jeremy piled up on himself wouldn’t go away, either. No more than people on this ship forgot the last Fletcher, shutting the airlock, and bleeding on the deck.

Jeremy was in one heavy lot of trouble for a twelve-year-old.

And he, Fletcher, simply Fletcher, was in one hell of a lot of pain of his own. Personal pain, that had more to do with things before this ship than on this ship.

What Jeremy had shaken out of him had nothing to do with Jeremy.

He stared at Jeremy, just stared.

“You said you weren’t going to give me hell,” Jeremy protested.

“I didn’t say I wasn’t going to give you hell. I said I wasn’t going to throw you out of here.”

“It’s my cabin!”

“Oh, now we’re tough, are we?” If he invited Jeremy to ask him to leave, Jeremy would ask him to leave. Jeremy had to. It was the nature of the kid. It was the stainless steel barricade a kid built when he had to be by himself.

“Jeremy.” Fletcher leaned forward on his bunk, opposite, arms on his knees. “Let me tell you. That stick’s sacred to the hisa, not because of what it is, but because it is. It’s like a wish. And what I wish, Jeremy, is for you to make things right with JR, and I will with Chad, because I was wrong. You may have set it up, but I was wrong. And I’ve got to set it straight, and you have to. That’s what you do. You don’t have to beat yourself bloody about a mistake. The real mistake was in not coming to me when it happened and saying so.”

“We were having a good time!” Jeremy said, as if that excused everything.

But it wasn’t in any respect that shallow. He remembered Jeremy that last day, when Jeremy had had the upset stomach.

Bet that he had. The kid had been scared sick with what had happened. And trying, because the kid had been trying to please everybody and keep his personal house of cards from caving in, to just get past it and hope the heat would die down.

House of cards, hell. He’d made it a castle. He’d showed up, taken the kids on a fantasy holiday; he’d cared about the ship’s three precious afterthoughts.

He knew. He knew what kind of desperate compromises with reality a kid would make, to keep things from blowing up, in loud tempers, and shouting, and a situation becoming untenable. That was what knotted up his own gut. Remembering.

“It wouldn’t have made me leave,” he said to Jeremy.

“Yes, it would,” Jeremy said. And he honestly didn’t know whether Jeremy had judged right or wrong, because he was a kid as capable as Jeremy of inviting down on himself the very solitude he found so painful—the solitude he’d ventured out of finally only for Melody and Patch.

And been tossed out of by Satin. To save Melody, Patch and himself.

Maybe the stick had a power about it after all.

He reached across and put his hand on Jeremy’s knee. “It’ll come right,” he said.

“It was that Champlain that took it,” Jeremy said. “I know it was. That skuz bunch—”

“Well, they’re a little more than we can take on. Nothing we can do about it, Jeremy. Just nothing we can do. Forget it.”

“I can’t forget it! I didn’t want to lie, but it just got crazier and crazier and everybody was mad, and now everybody’s going to be mad at me.”

He administered an attention-getting shake to Jeremy’s leg. “By now everybody’s just glad to know. That’s all.”

“I hurt the ship! I hurt you! And I was scared.” Jeremy began to shiver, arms locked across his middle, and the look was haunted. “I was just scared.”

“Of what ? Of me being mad? Of me knocking you silly?” He knew what Jeremy had been scared of. He looked across the five years that divided them and didn’t think Jeremy could see it yet.

Jeremy shook his head to all those things, still white-faced.

Afraid of being hit? No.

Afraid of having everything explode in your face, that was the thing a kid couldn’t put words to.

It was the need of somehow knowing you were really, truly at fault, because if you never got that signal then one anger became all anger, and there was no defense against it, and you could never sort it all out again: never know which was justified anger, and which was anger that came at you with no sense in it.

And, finally, at the end of it all, you didn’t know which was your own anger, the genie you didn’t ever want to let out– couldn’t let out, if you were a scrawny twelve-year-old who’d been everyone’s kid only when you were wrong. You were reliably no one’s kid so long as you kept quiet and let nobody detect the pain.