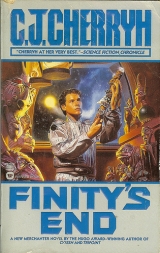

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“We’re supposed to stay in our bunks.”

“Hell.” The one time he wanted work to do. There was nothing. He was in a void, boundless on all sides. He sat down on his bunk and raked hands through his wet hair.

Satin. The stick he’d carried through hell and gone…

His brain began to look for bits of interrupted reality. Finally found the key one.

Voyager. “Where’s the ship we were following? Where’s Champlain ?”

“I don’t know,” Jeremy said in a hushed voice. “Nobody’s said yet. Fletcher, you’re being weird on me. You’re scaring me.”

“I want the stick back. I don’t care what kind of a joke it is, it’s over. I want it back. You think you can communicate that out and around the ship?”

“JR’s been looking for it. Everybody’s been looking. I don’t think they’re through—”

“ Then where is it? ” He scared Jeremy with his violence. He’d found the anger, and let it loose, but it didn’t have a direction anymore, and it left him shaken. “I don’t know whether JR might know all along where it is. And say I should just have a sense of humor about it. But I don’t. And for all I know the whole damn ship thinks it’s funny as hell.”

“No,” Jeremy said faintly. “Fletcher,—we’ll find it. We’ll look. They haven’t got us on any duty. We’ll look until we find it”

“Yeah. Why don’t we ask Chad along?”

“We’ll find it.”

“I think we’d have hell and away better shot at finding it if JR put out the word it had better be found.”

Jeremy didn’t say anything.

And he was being a fool, Fletcher thought. The vividness of the Watcher dream was fading. The feeling of loss ebbed down.

But the feeling of being robbed—not only of Satin’s gift, but of his own feelings about it—lingered, eating away at his peace. He’d come out of sleep in a panic that wasn’t logical, that was a weakness he’d gotten past. He’d changed residences before and thrown away everything when he got to the new one… photographs, keepsakes, last-minute, conscience-salving gifts. All right into the disposal, no looking back, no regrets. And yet—

Not this time.

Maybe it was the spite in this loss.

Maybe it was the innocence and the stern expectation in the giver…

Maybe it was his failure, utterly, to unravel what he’d been given, or why he’d been given it, or even whose it was.

Downers put them on graves. Put them at places of parting. Gave them to those who were leaving, and the ones who carried them from a parting or a death would leave them in odd places—plant them by the riverside, so the scientists said, in utter disregard that Old River would sweep them away next season… plant them in a graveyard… plant them on a hilltop where no other such symbols were in sight and for no apparent distinction of place outside the downer’s own whim.

And sometimes such sticks seemed to come back again. Sometimes a downer took one from a gravesite and bestowed it on another hisa and sometimes they returned to the one that had given the gift. One researcher had asked why, and the downer in question had just said, “He go out, he come back,” and that was all science had ever learned.

He go out. He come back.

To a graveyard, with more strings and feathers added. Researchers took account of such things, in meticulous studies that noted whether the sticks were set in the earth straight, or slanted, or if the feathers were tied above or below certain marks…

All that would mean things in the minds of the researchers, perhaps. He didn’t trust anything they surmised—he, as someone who’d been given one—someone who’d carried one as a hisa had to carry such a gift. He’d had no place to store it, no place to carry it…

And had the researchers with their air-conditioned domes and their cabinets and their classifying systems never thought what it was to carry one, with no pockets, ridiculous thought? When you had one in your trust, you just carried it, was all, and it was with you, and at some point in the next day or so after, he supposed downers felt a need to complete the job of carrying it, taking it to a grave, or to Old River, or to stand on some hilltop, nearest the sky, just to get on with their lives, get a meal, take a drink, do something practical.

He never got to find a place to let it go, that was the thing.

Satin gave it to him, laid the burden of it on him, saying… go to space, Fletcher.

He’d brought it here and in that sense he’d carry it forever if he couldn’t find it. He’d carry the burden of it all his life, if the people he’d been sent to, his own people, made a joke of it—if the ones who should accept him thought so little of him and all he’d grown up to value.

He raked the hair back, head in his hands, had, he thought to himself, a clearer understanding of Satin’s gesture and of his banishment than any behaviorist ever could give him.

Take this memory and go, Fetcher.

Be done with old things. Be practical. Feed yourself. Sleep. Let Melody go.

But that wasn’t all of it, even yet. It was Satin’s gift. It came from the one hisa who’d gone to space, and back again. It wasn’t just from any hisa. It was from the authority all hisa knew and all humans recognized. It was Satin’s gift and Base administration hadn’t dared say otherwise.

Then some stinking lowlife stole it, because an unwanted cousin came in as an inconvenience, one who had had some other life than the ship.

He didn’t think now that JR would have done it or countenanced it, but protect the party responsible and try to patch it all up? That was JR’s job, to keep the bad things quiet and keep the crew working. He figured the Old Man might not even have heard yet—if it was up to JR to report.

But no—he recalled now, piecing the details of pre-jump together: Madelaine knew. And if Madelaine knew, he’d bet the Old Man did know.

He didn’t think that the senior captain would approve such goings-on. In that light, it was well possible that JR had had to explain the situation.

A weight came on the bunk edge beside him. Jeremy. With an earnest, troubled look, itself an unspoken plea. He’d been seeing Downbelow, in his mind.

“The hell of it all is,” he said to Jeremy, “the stick was like a trust. You know what I mean? And if I get it back, I don’t know what I’d do with it… something Satin would want; but I don’t know.—But it’s for me to choose when and where to do that. Somebody else doing it… just tucking it away somewhere…” He was talking to a twelve-year-old, who, even with his irreverence, believed in things dim-witted twelve-year-olds believed, in magic, and a responsive universe, things somebody older could still in his heart believe, but never dare say aloud. “You know what that means? That they carry that stick. And that they’ve taken on responsibility for something they probably wouldn’t choose to carry, but I’ll tell you something about that stick. It won’t turn them loose. That thing’s an obligation, that’s what it is. And this ship won’t ever be quit of it if it doesn’t give it back to me.” He saw Jeremy’s face perfectly serious, absolutely believing. “And—no,” he said to Jeremy, “I’m not going to look for it. It’s going to come back to me or this ship will change and change into what somebody aboard wants it to be. I’m not going to play games with Chad about it. He’d better hope he finds it and gets it to me before the captain steps in to settle it, and I kind of think that’s the instruction the captain’s given JR. You understand me? If the ship doesn’t find it—it’s going to be the ship’s burden, and the ship’s responsibility, and as long as I live I won’t trust Chad Neihart. Maybe no one else will, either.”

“What if it’s not his fault?” Distress rang in Jeremy’s voice. “What if he, like, meant to give it back and something went wrong?”

“I said it. It’s something you carry until you can lay it down. Downer superstition, maybe. But it’s true. I can tell you, either I’m going to forgive Chad and his hangers-on, or I’m not. And I’m going to trust this ship or I’m not. That’s the kind of choice it is. You can pass that word where you think it needs to be passed. Things people do don’t altogether and forever get patched up, Jeremy, just because they’re sorry later. If Chad destroyed it… that says something it’ll take years for me to forget.”

There was a long and brittle silence.

“He’s not a bad guy,” Jeremy said faintly.

“Can I trust him after this?” he asked. Yes, Jeremy believed in miracles, and balances. And maybe it was callous to trade on it, but, dammit, he believed such things himself, and maybe belief could motivate one other human being in the crew. “Can I ever trust him? That’s the question, isn’t it?”

Jeremy didn’t have an answer for him, even with a long, long wait. Just: “I’ll put the word around. This shouldn’t have happened. It shouldn’t, Fletcher. We’re not like that.”

“I want to think so,” Fletcher said. It was, at least in that ideal world of these few moments’ duration, the truth. Then, because the ensuing silence grew uncomfortable: “Are they going to open rec, do you think, or not?”

“I think we’re supposed to sit in quarters. At least until they give us a clear. I’ll lend you my tapes.”

Fletcher got up and walked the six steps the cabin allowed before he fetched up in front of the mirrored sink alcove. He saw Jeremy standing, too, watching him with a distressed look on his face.

“Cards,” he said to Jeremy, foreseeing otherwise Jeremy worrying at the matter and himself pacing twelve steps up and back, up and back, for a long, long number of hours. It was a situation Jeremy knew how to endure, this being pent in quarters. He imagined the rule in force at other chancy moments, on Finity ’s exits into lonely star systems, and the too-wise twelve-year-old with nothing and no one to confide in.

Don’t leave . He remembered Jeremy pleading with him, in a way that, maybe hearing it when he was tranked, the way it did with tape-drugs, had settled into his consciousness with peculiar force. He’d had borrowed brothers all his life. He’d never had a foster brother as desperate, as lonely as Jeremy. There’d never been a rivalry between them. Now—he began to see Jeremy adopting his trick of leaving the coveralls collar undone, his trick of how he did a hitch in the belt—

Even the cuff turn-up. The obsession, when they’d been on liberty, with finding a sweater, a brown sweater, like his. God, it was laughable.

And enough to grab his heart, when he looked at the kid’s face, the eyes that searched his for every hint of advice, and, having just evoked it and brought it into the open, how did he ignore it?

He didn’t know how he felt now. Trapped, yes.

And at the same time gifted with something he’d never had, and now couldn’t walk away from… no more than Melody had walked away from a lost boy that day on Pell docks.

Chapter 20

Voyager lay ahead, a spark against a starry dark, swinging in orbit about a stony almost-planet itself orbiting a smallish star.

No Boreale . No Champlain when Finity had broken out of hyperspace here. Just the ion traces of ships that had come in…

And gone. Both. Champlain in the lead, one guessed, and Boreale in pursuit. A nominally Alliance ship fleeing; and a Union ship, which without their permission couldn’t hunt in this space, in hot pursuit

The feeling on Finity ’s bridge was one of frustration. It was second watch in charge of the jump out of Mariner-Voyager Point. That was Madison’s crew, with Francie’s watch coming on—third watch; and for a buffer, and to handle emergencies, and the senior-juniors, who’d fought the ravages of a double-jump and hauled their depleted bodies out of bunks faster than no few of the seniors could… anticipating the remote possibility of battle stations, and moving to be there in case one of the seniors couldn’t make it to station.

JR held the lead of that set.

But nothing. Just nothing. They turned out to be alone in the jump range, and that was, for the ship, good news. JR told himself so—even if Madison hovered after turnover with a general glum look, and even if Helm 2 had stayed around to be a problem to Helm 3.

Battle nerves, with no battle, no answer, even, for simple human curiosity—and the suspicion that a Union ship had just slipped their witness in Alliance space with full opportunity to carry out an attack on what was, nominally, still an Alliance ship.

That was JR’s suspicion, at least. And at a time when they were trying their damnedest to persuade Alliance merchanters to surrender to the Alliance station-based government at Pell some of the rights Finity’s End had once been pivotal in winning.

Ignore the fact our Union ally just took out after an Alliance ship… and did it one jump short of Esperance, the hardest sell they’d face? No matter that that Alliance ship might be guilty of aiding the enemy, the enemy that had not that long ago been their own Fleet; and no matter that some Alliance merchanters were caught on the wrong side of the line. The Alliance found it hard to forgive Union, who’d roughly handled some merchanters during the War and whose territorial lines were now trying to choke some merchanters out of business.

Alliance was very ambivalent about rimrunners, ships skirting the edges of the modern international alignments; and about dealings with Union; and while they wanted Mazian kept at bay, it was not a universal sentiment that the Alliance could exist without the bugbear of Mazian out in the dark—because that fear kept Union behaving itself.

A Union ship taking on a merchanter would harden Alliance merchanter attitudes at the same time it might incline Esperance Station attitudes toward an agreement with Union. Get-tough policies regarding merchanter compliance weren’t going to win points with the small merchanters who were one economic catastrophe away from having to run cargo they wouldn’t ordinarily choose to be running. JR didn’t know what the Old Man thought of the situation. He hoped that the ion signature they picked up was of a passage, not a battle shaping up to happen in the witness of Esperance and anyone docked there.

He’d bet first that the Old Man, who was not on the bridge this jump, was well aware, and second, that the Old Man was not amused at Boreale’s giving chase past Voyager without consultation. Likely he was already considering how he was going to counter the negatives if the situation blew up.

They had, JR concluded, a potential problem. They’d given Boreale what Boreale couldn’t otherwise have gotten: a straight short-cut through Alliance space to warn the Union’s own presence at Esperance—reputedly there was a major one at all times—that there was something in the offing. And that could be bad news—or good

There was no possibility that the carrier they’d met at Tripoint had sent Boreale : arrival times at Mariner didn’t make it possible, but he was curious enough to sit down and call up Mariner data to confirm that Boreale had, indeed, been in port for a week before they’d gotten in. No. Even granted ships could over-jump one another in hyperspace, that theory didn’t fit the timeline.

Boreale had come in from Cyteen vector and it had no possibility of having been sent by Amity . So its being there was honest.

Boreale’s guarding them in the understanding that they were trying to get merchanters into compliance with the customs regulations, that was honest, too.

So it was perfectly reasonable, aside from chasing Champlain , that they would want to get on through to Esperance where, unlike at Voyager, they had a straight shot to carry a message to Cyteen and could equally well contact other ships whose black boxes had been in very latest communication with Cyteen, to check out what was going on elsewhere. In Boreale’s situation, they’d have done exactly the same.

The Old Man had played it safe, and here they were. They had to go in at Voyager, refuel, do their business of meetings with station administration, and go through the routine motions of trade. They wouldn’t slight Voyager by bypassing it

The good break was that, in the slight imprecision of ship arrivals in a gravity well, Helm had used the belling effect of a ship still at the interface to skip a moderately loaded and very powerful ship well out even from the center of system mass, which wasn’t the center of the star… and the direction of that skewing was toward the position Voyager station happened to be at this time of its year. It was a beautiful job both from Nav and from Helm, a piece of skill that had, all at the same time, simplified their dive toward the station, let them speed faster longer than they’d dare at larger stations, and given them a chance of making up time in what had become a race with Boreale toward Esperance.

Ahead was the least modern station still functioning this side of Union, a small station, with part of its ring under construction before the War, a construction, their files said, which was now abandoned.

Pell, Mariner, Earth… Cyteen, as well, had strung multiple establishments through the ecliptic of their stars. But impoverished Voyager was just Voyager, in orbit about a tiny planet near a debris ring unpleasantly perturbed by a smallish gas giant. Voyager had built a watchful defense not originally against piracy but against high-velocity visitors. But its capabilities had found dual use during the War—use which had kept it alive and kept it a port of call for whatever side could hold it.

And that had been Mazian, for most of the War years.

Prior to the War, in the days of shorter-hopping ships, Voyager had been a bridge toward the hope of more exotic mining at Esperance, but in post-War years, mining had turned out less lucrative for Esperance than the lure of trade with Cyteen. Mariner also wanted the promise of traffic between Pell and Cyteen, if the peace held. Now, poised between Mariner and Esperance, Voyager was the unfortunate waystop between two stars only fragilely interested in trading with each other.

There was a time crunch on. They had a very little time at this star to turn that situation around.

The Old Man arrived on the bridge. Madison and Alan alike stood up. JR did, and all the other juniors on the bridge, in respect of the senior captain, who waved them to be seated.

Madison delivered the first report, of which JR caught the salient details. Alan delivered the second one. Frances had shown up in James Robert’s wake, to hear the general reports, and JR listened on the edges, aware of Bucklin having moved up near him.

“Well,” the Old Man said with a wry expression that framed official reaction, “we have a need to get through this port and get our job done. We are going to get turned around and get out of here in record time. All senior crew to round the clock hull watch, all able-bodied to transfer of cargo, senior staff to what I hope will be short meetings. I don’t anticipate station will object to our proposals at all, but the local merchant trade is likely to. And I’d rather have had Boreale here with us. But we don’t have that. What does the schematic show us? Who’s in port?”

“That’s three interstellars, sir,” Alan said, “end report.”

That was incredibly thin traffic.

“We mustered better than that at our last conference with Mallory,” the Old Man said with a shake of his head. “Jamie. Who are they? Mariner origin or Esperance?”

“ Velaria left Mariner for Voyager a week ago, sir, Constance and Lucky Lindy were before that. Nothing but ourselves, Boreale , and Champlain the last five days. No ships from Esperance in port.”

“Counting that a week’s rated a long stay here, it’s a reasonable expectation, three ships. Voyager’s apt to berth about five ships on any given twenty-four hours, rarely ten. We’re the fourth. Boreale and Champlain would have made it almost to traffic congestion, for this port.”

“Yes, sir,” JR said. He’d been ready. It was a struggle, on a two-jump, to have mental recall on everything you’d been supposed to track. It was a job skill. A vital one, and he hadn’t failed it.

“Four empty cans,” the Old Man said, “food grade and clean, ride in the hold. The job will be to test and transfer whatever we pick up on the local market to assure ourselves a clean cargo, one can to the other. Senior crew will not have forgotten this drill, our compliments to the junior crew, who will carry out a great deal of the transfer. We will secure lodgings for all crew near the ship, and crew will not separate from assigned groups, no matter what the excuse. We will make an additional issue of clothing, purchased at the station. We will forego ship’s rules on patches and tags. Wes, you’ll treat the details in a general announcement. The station could use the trade, and we won’t have access to the laundry. Junior-juniors will stay particularly close, within safe perimeters, and only senior staff will deal with food procurement, clothing issue, all other activities where something from the outside comes aboard this ship, including personal baggage, which will be extremely limited. Security Red applies. Cargo will, however, be inert.”

It was the old New Rules. Nothing came aboard without being scanned through, logged, accounted for, and the crew member in question absolutely able to vouch for its integrity. Security Red usually applied when they were hauling touchy cargo… explosives, not uncommonly in the past. This time it wasn’t the cargo’s volatility that prompted the precautions against sabotage. It was Voyager’s.

The Old Man walked about then, taking a short tour past the number one stations, the general boards, spoke a word with the Armscomper, who’d only begun to shut down the hot switches, and with Tech 1, who’d handled the tracking on the emissions signatures.

Habitually the Old Man also said a word to the observing staff, as they called it: the senior-juniors, and JR waited, standing.

“I had a memo from Legal before jump,” the Old Man said in a lowered voice. “I’d like to see you in my office. Now.”

“Yes, sir.” It was not a topic he wanted to deal with on the bridge. It wasn’t a topic he wanted to deal with. And had to.

The Old Man left the bridge. JR looked at Bucklin, who cast him a look of sympathy, and went to report a situation he’d hoped, pre-jump, to have solved.

“The situation on A deck,” the Old Man said with no preamble, as JR stood in front of that desk in the Old Man’s office, the one with the bookcases, the mementoes of old, wooden ships. Past the Old Man’s iron control, JR had no difficulty detecting distress: personal, distracting distress, which the senior captain could well do without when he faced life and death decisions, peace and war decisions.

“Not the captain’s immediate concern, sir. I hope to have a solution.”

“We’ve never had to use the word ‘theft.’ ”

“I’m well aware, sir. I don’t know what to say. I don’t have an answer.” At that moment a message began on the intercom, a general advisement to the ship that Boreale and Champlain had slipped through Voyager system and that they were proceeding to dock and refuel.

“ Security Red will apply here ,” the intercom said, Alan’s voice, “ and we will be shifting cargo. The fact that Boreale has gone on in close pursuit of Champlain remains a matter of concern, but it is not, at the moment, our concern …”

James Robert’s finger came down on the console button and the announcement fell silent in the small office.

“I think we know those details.”

“Yessir,” JR said.

“A spirit stick as I understand it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Smuggled aboard.”

“Technically, yes, sir.” It wasn’t the illegality of it that he felt at question, but the very question how anything of that unusual a nature had gotten past his observation. “Legally in his possession.”

Sometimes in the tests the Old Man set him he had to risk being wrong. “Sir, I haven’t considered what the case is. Evidence points to someone taking it, I’ve requested its return, and no one’s come forward.”

“And there’s been a fight.”

“Yes, sir. There was a fight.” Sometimes, too, the challenge was to hang on to a problem and keep it off B deck. And conversely to know when to send it upstairs. “I’d like to continue to handle this one, sir, on my own resources.”

There was a long, a very long silence. If there was a space under the carpet he’d have considered it. As it was he had to stand there, the subject of the senior captain’s very critical scrutiny at a time when a very tired, very worn-looking senior captain took spare moments out of his personal rest time, not his duty schedule.

“I take it the investigation is not at a standstill.”

“No, sir. Ship movement took precedence, but this can’t end with an acceptance of this situation. That won’t solve it.”

The captain nodded slowly, in concurrence with that assessment, JR thought.

They risked losing Fletcher. That was one thing. They risked setting a precedent, a mode of dealing with each other that might destroy them.

“Ship’s honor,” JR said faintly, in the Old Man’s continued silence. “I know, sir.”

“Ship’s honor,” the Old Man said. “It’s the means by which we dare ask those other ships, Jamie, to put aside self-interest. In the last analysis, it’s the highest card we have. Think about it. Do we wish to give that up?”

“No, sir.” It was hard to make a sound at all. Hard to breathe, until the Old Man dismissed him to the relative safety of the corridor.

Five minutes later he gave Bucklin and Lyra orders.

In fifteen minutes, every unassigned junior including Fletcher was on intercom-delivered notice that the Old Man had inquired about the object; and juniors were spreading out through the ship this time on independent, not team, search.

Give the culprit the opportunity to find the object, in whatever way he or she wished. It wouldn’t end it, but it would enable him to put the focus on the interpersonal problem and discover what they were actually dealing with: a theft, or the ruse, or the destruction of something irreplaceable.

Fletcher, however, was with the junior-juniors, all three, when he came on them going through A deck’s vacant cabins a search that, in the example he saw, had boxes of whiskey moved, storages opened, bunks swung to look underneath, all with amazing dispatch.

“Fletcher,” JR said, and drew Fletcher outside the door to 40A. “The Old Man expresses extreme concern. It’s not a property issue. I don’t consider it one. He doesn’t. If you want to file a complaint with him, that door will be open. I’m asking you, personally, give me time to unravel this.”

Fletcher had been moving boxes. His breaths came deep. “I didn’t intend to get involved,” Fletcher said, and gave a move of the eyes toward the flurry of activity inside. “They wanted to.”

If it had been any other circumstance, he would have been dismayed at the thought of the inexpert junior-juniors disarranging cargo. Thumps continuing to come from inside the disused cabin. “I’m impressed with their enthusiasm,” he said.

And in the uneasy silence that followed between them: “Fletcher, we’re approaching a very dangerous dock. I hope we can resolve things prior to docking. If not, I’m asking you, as I’ll ask Chad, to refrain from confrontations. Very serious negotiations are riding on it. Alliance-Union negotiations. They could be adversely affected if two of our crew engage on dockside.” There was a moment more of silence, and diminishing hope of Fletcher’s understanding. “I’m asking your cooperation for a handful of days. We’re going to be working hard, tempers are going to be short. You’re assigned to watch the junior-juniors, the same as before, but I can take you off that if you feel you’d be better separated from other personnel. You and the junior-juniors can sit in a sleepover together and watch vids, if that’s your choice, and you won’t have to work.”

Fletcher stood there considering what he said. He increasingly expected Fletcher to choose to stay to the sleepover, the safest choice, and the one, in the absence of Fletcher’s desire to cooperate, he still might order.

But Fletcher let go the frown, and glanced instead toward the doorway, where the junior-juniors were conducting their search. Then he looked back.

“Even if provoked,” Fletcher said. “As long as we’re in dock. You’ve got my promise.”

“I’m glad to take your word,” he said, and left the junior-juniors to their activity. He hunted down Chad with the same proposition, and that quest required a trip out into the rim, where in coats and gloves and with flashlights, Chad had paired up with Wayne. Another glow, from around the girder-laced curve, showed where Nike and Lyra were operating, in cold deep enough to get through boots.

“I don’t know why he picked me,” Chad said “That’s twice he’s come at me like I was the only one.”

“I don’t know why,” he said “I can’t defend it. I only know how important it is we keep the peace. On both sides of this.”

“I don’t even know what the damn stick looks like,” Chad said. “It’s hard to search for something when you only have a description of it. And that’s all I have.”

Chad wanted to convince him he was innocent. He wished he believed it himself. And yet he couldn’t dismiss the possibility it was the case. “It’s all I have, too,” he said to Chad.

“I think he did it,” Chad said, breath frosting in the light, “and he’s just putting us to running rings. I think it’s going to turn up somewhere and he’ll be the only one not surprised.”

“If that’s the case,” he said. “If it’s not the case, the real way this is going to get solved is when we sit down together and look at each other without suspecting the worst. Him. You. Wayne. Me. All of us.”

“Chad’s taking the brunt of this,” Wayne said. “And I don’t think he’s to blame.”

“He doesn’t want to be here, anyway,” Chad said.

“And I just talked to the Old Man, and asked for more time. Give me some help, Chad.”

“Yessir. I won’t fight.”

He had a confidence in Chad he couldn’t have in Fletcher, who hadn’t been a presence all his life. Chad might be on the wrong side of something, but he wouldn’t go against the answer he’d just given.

“Not even if he jumps you, Chad. If he does I’ll settle it. I know it’s hard what I’m asking, but you’re both of you strong hands we need, and I’d rather not have you sitting it out in quarters.”