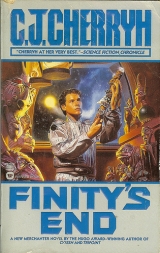

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

It was as advertised, the senior-juniors with a table staked out and a festive occasion underway. Wayne set a hand on his back and steered him toward the group. JR beckoned him closer.

He took it for an order, set his face and walked up to the table… where Lyra cleared back, Bucklin pulled up a chair, and JR signaled service. Chad was there, Nike, Wayne, Sue, Connor, Toby, Ashley… the whole batch of them.

“Our novice here just shed three offers,” Wayne announced. “They’re in tight orbit about this lad.”

“Not surprised,” Lyra said. “I would, if he weren’t off-limits.”

“You would, if you weren’t off-limits,” Connor gibed. “Come on, be honest.”

He wasn’t sure whether that was a joke at his expense or not, but the waiter showed up and asked him what he was drinking. He took a chance and ordered wine.

Talk went on around him, letting him fall out of the spotlight. He was content with that. They talked about the sights on the station. They talked about the progress of the loading, they talked about the rowdy arrival—it was a freighter named Belize , a small but reputable ship, no threat to anyone—and he had his glass of wine, which tasted good and hit a stomach long unaccustomed to it. Chad ordered another beer. There were second orders all around.

“I’d better get up to the kids,” he said, and got up and started to move off.

“Good job,” JR said soberly. “Fletcher. Good job. If you want to stay another round, stay.”

“Thanks,” he said, feeling a little desperate, a little trapped. More than a little buzzed by the wine. “But I’d better get up there.”

“Fletcher,” Lyra said “Welcome in.”

Maybe it was a test. Maybe he’d passed. He didn’t know. He offered money for his share of the tab, but JR waved it off and said it was on them.

“Yessir,” he said. “Thank you.” He escaped, then, not feeling in control of the encounter, not feeling sure of himself in his graceless duck out of the gathering and out of the bar.

But they’d invited him. His nerves were still buzzing with that and the alcohol, and if spacers from Belize tried to snag him he drifted through them in a haze, unnoticing. He rode the lift up to the level of his room, got out in a corridor peaceful and deserted except for a slightly worse for wear spacer from Belize , and entered his palace of a room, where he had every comfort he could ask for.

He’d written to Bianca. Things aren’t so bad as I’d thought …

This evening he undressed, showered, and flung himself down in a huge bed that, as Jeremy had said, you almost wanted safety belts for… and thought about Downbelow, not from pain this time, but from the comfort of a luxury he’d not imagined. Memories of Downbelow came to him now at odd moments as those of a distant place—so beautiful; but the hardship of life down there was considerable, and he remembered that, too—only to blink and find himself surrounded by the sybaritic luxury of an accommodation he’d never in the world thought he could afford. He had so many sights swimming in his head it was like the glass-walled water, the huge fish patrolling a man-made ocean. His worlds seemed like that, insulated from each other.

His hurts tonight were all in that other world. He’d felt good tonight. He’d been anxious the entire while, not quite believing it was innocent until he was out of that bar without a trick played on him, but his cousins had made the move to include him, and he discovered—

He discovered he was glad of it.

He shut his eyes, ordered the lights out…

A knock came at the door. A flash at the entry-requested light .

Cursing, he got up, grabbed a towel as the nearest clothing-substitute, and went to see who it was before he opened the door.

Jeremy.

“What’s the trouble?” he asked, and didn’t bother to turn the lights on, standing there with a bathtowel wrapped around him and every indication of somebody trying to sleep.

“Vince and Linda went downstairs. I told them not to. But you weren’t here. And they said they were going down to check…”

“I’m going to kill Vince,” he said. “I may do it before breakfast.” The lovely buzz from the wine was going away. Fast. He leaned against the doorframe, seeing duty clear. “Tell you what. You go downstairs, you tell them we just got a lot of strangers off another ship, some of them are drunk, and if they don’t get their precious butts back up here before I get dressed and get down there, they’re going to be sorry.”

“I’m gone,” Jeremy said, and hurried.

He dressed. There was no appearance at the door. He went downstairs, into the confusion of more Belize crew of both genders in the lobby, wanting the lift, noisy, straight in from celebrating their arrival in port—and their collection of spacers of different ships, not Belize and not Finity . He escaped a drunken invitation and escaped into the game parlor where Belizers were the sole crew in evidence—except the juniors, in an open-ended vid-game booth in which Jeremy, not faultless, was an earnest spectator.

Then Jeremy spotted him, and with a frantic glance tugged at Linda to get her attention to approaching danger. Vince, his head in the sim-lock, was oblivious until he walked up and tapped Vince on the shoulder.

Vince nearly lost an ear getting his head out of the port.

“You’re not supposed to be down here without me.”

“So you’re here.”

“I’m also sleepy, approaching a lousy mood, and the crowd in here’s changed,” Fletcher said.

“You don’t have to be in charge of us,” Vince said. “You’re younger than I am!”

“So act your age. Upstairs.”

“Chad never chased after us.”

“Fine. I’ll call Chad out of the bar.”

“No,” Linda said “We’re going”

“Thought so,” he said “Up and out of here.” He’d been a Vince type, once upon a half a dozen years ago. And it amazed him how being on the in-charge side of bad behavior gave him no sympathy. “Come on. I’m not kidding.”

“We weren’t doing a damn thing!” Vince said

“Come on,” He patted Vince on the rump. “Still got your card wallet?”

Vince felt of the pocket. Fast. Frightened.

“Your good luck you do,” he said, and gave it back to Vince.

“Yeah,” Jeremy said mercilessly. And: “That’s wild. How’d you do that?”

“I’m not about to show you.” He put a hand on Jeremy’s back and on Vince’s and propelled them and Linda through the jam of adult, drunken Belizers at the door. “Up the stairs,” he said to them, figuring the lifts were likely to be full of foolishness, and unidentified spacers. He thought of resorting to JR, then decided it was better to get the juniors into their rooms. He escorted them up three flights, unmolested, onto their floor, just as a flock of spacers arrived in the lift and came out onto the floor, with baggage, checking in, he supposed, but the situation was clearly different than what seemed ordinary.

“In the rooms and stay there,” he said, with an anxious eye to the situation down the hall, where somebody was fighting with a room key. “Is it always like this?” he had to ask the juniors.

“No,” Jeremy said.

It was supposed to be a tight-rules station. He knew Pell would have had the cops circulating by now. “Keep the doors locked,” he said, saw all three juniors behind locked doors, and went back down the stairs.

A Finity senior in uniform met him, coming up: the tag said James Arnold .

“We’ve got kind of a rowdy lot up there,” he said to his senior cousin.

“Noticed that,” Arnold said. “Where are you going?”

“JR,” he decided, his original intention, and he sped on down the stairs to the lobby, eeled past a couple more of the rowdy crew, and started through the lobby with the intention of going to the bar.

JR, however, was at the front desk talking urgently to the manager.

He waited there, not sure whether he’d acted the fool, until JR turned away from the conversation, the gist of which seemed to be the Belize crew.

“We’ve got them on our floor,” he said to JR without preface. “James Arnold just went up there.”

“Good,” JR said. “Were they all Belize ?”

“Some. Not all.”

“It’s all right. Management screwed up, but we’ve checked some personnel out to other sleepovers and they just put ten Belizers up where we’d agreed they wouldn’t be. They’ve a little ship, an honest ship, that’s the record we have. Just louder than hell. Just keep your doors locked. It’s not theft you have to worry about.”

He didn’t understand for about two beats. Then did. And blushed.

“Seriously,” JR said, and bumped his upper arm. “Go in uniform tomorrow. Juniors, too. That’ll cool them down. Their senior officers know now there are Finity juniors on the third floor. Keep an eye on who comes in, what patch they’re wearing. We’ve got lockouts on China Clipper, Champlain, Filaree , and Far Reach , for various reasons. If you see those patches, I want to know it on the pocket-com.”

“What about the ones that aren’t wearing patches?”

“We can’t tell. That’s the problem. But it’s what we’ve got. Keep the junior-juniors glued to you. The ships I named are a serious problem in this port. Most are fine. But some crews aren’t.”

JR went off to talk to senior crew. He went back upstairs, not sure what to make of that last statement, thinking, with station-bred nerves, about piracy, and telling himself it might be just intership rivalry, maybe somebody Finity had a grudge with, and it wasn’t anything to have drawn him in a panic run down-stairs, but JR hadn’t said he was a fool. He picked up more propositions on his way through the crowd near the bar. A woman on the stairs invited him to her room for a drink—“Hey, you,” was how it started, to his blurred perception, and ended with, “prettiest eyes in a hundred lights about. I’ve got a bottle in my kit.”

“No,” he said “Sorry, on duty. Can’t.” He said it automatically, and then it occurred to him how very much the woman looked like Bianca.

He was suddenly homesick as well as rattled. He gained his floor, where Arnold, in Finity silver, was conspicuously on watch. He felt strangely safer by that presence, and his mind skittered off again to a pretty face and an invitation he’d just escaped just downstairs.

Gorgeous. Not drunk. And part of a problem that his ship’s officers had sallied up here to head off. A problem that had chased the small-statured juniors to their rooms.

Interested in him , he thought dazedly as he put his keycard in the door slot. Interested not because he was from Finity and Finity was rich. He was in civvies. He could have been anybody. She was interested in him . That absolutely beautiful woman had wanted him.

His door opened. He made it in. Undamaged. Alone. Safe with the snick of that lock, and telling himself there had to be something critically wrong with his masculinity that he hadn’t said the hell with the three brats and gone off with the most glamorous—hell, the only invitation of his life, including Bianca.

Intelligence, something said. Even while the invitation stayed a warm and arousing thought. He’d made it through a spacer riot, well… at least a moment of excitement that had gotten the officers’ attention. His encounter on the stairs was probably a wonderful young woman. He might even meet her in the morning… but no, he had specific orders to the contrary. And what she wanted was too far for a stationer lad on his first voyage and she was…

What was she, really, looking maybe late twenties?

Thirty? Forty?

He felt a little dazed. Not just about her. He’d caught invitations from all over. He, Fletcher Neihart, who’d only in the last year gotten a real date. He didn’t know why the woman had looked at him, except here he didn’t have a rep as a trouble-maker working against him.

Maybe he had shiny-new written all over him. Maybe—

Maybe what that woman had seen was a man, not a boy. Maybe that was who he could be.

He phoned the kids to be absolutely sure they were in their rooms and assured them there was a Finity senior on watch. He had another shower after all that running up and down stairs, and flung himself down in bed, in soft pillows, with his hands under his head.

The ceiling shifted colors subtly, one of the room’s amenities—something just… just to be pretty. Something you had to pay for. And spacers lived like this. Rich ones did… unlike anything he’d ever experienced.

But that was a bauble. The warmth in the bar tonight, the acceptance with JR’s crowd, that they hadn’t been obliged to offer him—the pretty young women trying to attract his attention, that was the amazing thing in his days here. And tonight, the knowledge, dizzying as it was, that when things went chancy he wasn’t alone, he wasn’t counted a fool, and he had a shipful of people to turn up as welcome as Arnold and JR had done, to fend off trouble and know solidly what to do.

It was damned seductive, so seductive it put a lump in his throat despite the thin sounds of revelry that punctured the recent peace.

Did he still miss Downbelow? He conjured Old River in his mind, saw Patch laughing at him from the high bank, and yet…

Yet he couldn’t hear the sound, not Patch’s voice, not Melody’s. He could only see the sunlight and the drifting pollen skeins. He couldn’t remember the sounds.

And Melody and Patch by now believed he’d gone… Bianca had gone on with her studies, passed biochem, he did hope. What could she possibly know about where he was?

He’d written to the Wilsons. I’m fine. I’ve done a lot of laundry. Now they’ve put me in charge of the kids. Who are older than I am. You’ll find that funny. But my station years count, and they’re far smaller than I am. I’m back doing vid-games and losing… I know you’ll be amused…

To Bianca he’d begun to write I love you … and he’d stopped, in the sudden knowledge that what they’d begun had never had time to grow to that word. He’d agonized over it. He’d not even been able to claim a heartfelt I miss you … because he’d gotten so far away and so removed from anything she’d understand that he didn’t think about her except when he thought about Downbelow.

He’d written… instead. …I think about you, I wish you could see this place. It seems so close to Pell, now. Before, it seemed so far …

He’d written… in a crisis of honesty… I’ve kind of bounced around, people here, people there. I’ve never dealt with anybody I didn’t choose …

If he added to that tonight, he’d write .. . I don’t think any group of people since I was a kid ever looked me up and invited me in… but they did that, tonight. It felt …

But he wouldn’t write that to Bianca, no admission she wasn’t the one and only of his life… you weren’t supposed to tell a girl that. No admission he’d had a dozen offers tonight. No admission he’d felt excited…

No admission he’d been scared as hell walking up to that group in the bar, and sure they were going to pull one on him, but he’d gone anyway, because he wanted… wanted what they held out to him. He wanted inclusion. A circle closing around him. He’d never felt complete in all his life.

He disliked Chad and Sue and Connor with less energy than he’d felt before he’d spent a few days ashore. Now they were familiar faces in a sea of strangers. He’d ended up talking to the lot of them, who’d made nothing of any grudge he had. He’d just been in , and the double-cross and the pain and the bruises and everything else had added up simply to being asked to that table to break one of JR’s rules and to be regarded as one of them, not one of the kids.

That event was unexpectedly important to him, so important it buzzed him more than the wine, more than the woman trying to make connection with him, more than anything that had happened.

It’s a setup , he kept saying to himself. He’d believed things before. He’d even believed one of his foster-brothers making up to him, best friends, until it turned out to be a setup, and a fight he’d won.

And lost. Along with childish trust

He was dangerously close to believing, tonight, not the way he’d believed in Melody and Patch, nothing so dramatic…just a call to a table where he’d not been remarkable, just one of the set. He was theirs, because they had to find something to do with him. Making his life hell had been an option to them, but not the one they’d taken.

It was better than his relations with people at the Base, when he added it up. He’d come in there determined to succeed and George Willett, who’d planned to do just the minimum, had instantly hated him, so naturally the rest had to. He’d come aboard Finity mad and surly, and JR, give him credit, had been more level-headed than he had been, more generous than he had been…

He didn’t exactly call truce or accept his situation on Finity . But for the first sickening moment… he wasn’t sure if he knew how to get home again. The first actual place he’d visited, and he felt… separated… from all he had known, and connected to the likes of JR and Jeremy and a grandmother who gave him a handful of change on a first liberty.

He didn’t know what was the matter with him, or why a handful of change and a drink in a bar could suddenly be important to him… more important than two downers he’d come to love. It was as if he had Downbelow in one hand and Finity in the other and was weighing them, trying to figure out which weighed the heaviest when he couldn’t look at them or feel them at the same time.

It was as if the sounds had come rushing back to him and he could see Melody saying, in her strange, lilting voice, You go walk, Fetcher?

You grow up, Fetcher?

Find a human answer… Fletcher?

Maybe he had to take the walk. Maybe the answer was out there.

Or maybe it was in that unprecedented come and join us he’d, for the first time in a decade, gotten from other human beings.

“If Pell reaches agreement,” the Mariner stationmaster said, and James Robert declared, “Then bet on it. It’s surer than the market.”

Senior captains of a significant number of ships in port had happened to have business on Mariner’s fifth level Blue at the same time, and found their way to a meeting unhampered this time by Champlain’s attempts to get into the circuit of information. Champlain was outbound this morning, and good riddance, JR thought, if Champlain weren’t headed to their next port

But in the kind of dispensation Finity had long been able to win on credentials the Old Man swore they’d resigned, the Union merchanter Boreale changed its routing and prepared an early departure.

In the same direction.

“If the tariff lowers and the dock charges lower,” the senior captain of Belize said, “we’d sign.”

Talk of tariffs and taxes, two subjects JR had never found particularly engaging until he saw the looks on the faces around him, senior captains of ships larger than Belize looking as if they’d swallowed something sour.

Belize , a small, old ship, incapable of doing much but Mariner to Pell, Pell to Viking and back again, saw its economics affected if the agreement of Mariner and Pell pulled Viking into line with that agreement. Viking’s charges, JR was learning, were a matter of complaint among Alliance merchanters—while Union willingly paid the higher fees, for reasons Alliance merchanters saw as simply a pressure against them, encouraging the stations to excess.

A junior supplying water and running courier, as he’d been asked to do, he and Bucklin, could learn a great deal of tensions he’d known existed, but which he’d never mapped—the narrow gap between a station’s charges for supplying a port and a ship’s costs of operation, a slim gap in which profit existed for the smaller carriers.

But there were the windfall items: the few ships that had the power to make the runs to Earth, in particular, had enormous opportunity… and to his stunned surprise, the Old Man put that extreme profit up for trade as well.

A cartel, skimming off that profit, would assure the survival of the marginal ships, the old, the outmoded. An entire system of trade, giving critical breaks to the smaller ships.

“It won’t work,” Bucklin had said in the rest break after they’d first heard it. “We’ll take less for our goods?”

“If the little ships fail,” he’d said to Bucklin, the argument he’d heard from the Old Man, himself, “Union’s going to move in.”

Bucklin thought about that in long silence.

When that argument was advanced to them, the other captains had much the same reaction—and came to much the same conclusion.

Then it seemed the major obstacle would be Union.

But, JR reasoned for himself, and saw it borne out in arguments he was hearing, Union, growing among stars they had only vague reports of, responded to the pirate threat with a fear out of all proportion to the size of the Mazianni Fleet.

Probably it had to do with the fact that Union had been consistently outpiloted, outgunned, and outflanked.

Possibly it even had to do with fear of a third human establishment in space, an admittedly unhappy situation they’d all talked about aboard, but only in the small hours of the watches and not in public. Union set great importance on planning the human future, and a third human power arising from a base somewhere outside their knowledge might not be a comfortable thought for them.

“What we have,” the Old Man said now in his argument to the gathering of captains and Mariner Station administration, “is a shadow route and a shadow trade that’s running clear from Earth, dealing in exotics like whiskey, woods, that sort of thing, biologicals funneled on the short routes out of Sol… one ship we did catch, Flare , a Sol-based merchanter doing short-haul trade—not necessarily with Mazian, but for Mazian.”

“Mazian’s getting the profit, you mean.” That was Walt Frazier of Lily Maid , a small hauler, an old acquaintance of Madison’s and the Old Man, by what JR guessed.

“There’s a well-developed shadow trade at Earth,” the Old Man said. “As you may know. Mars is a rich market. Luxury goods get off Earth, they go toward Mars. A certain amount doesn’t get there… written up as breakage during lift, just plain left off the manifests. And the mini-network leaks a certain amount via short-haul suppliers right on the docks of Sol One… but there’s a fairly brazen trade—or there’s been a fairly brazen trade—siphoning off goods to ships the like of Flare and several others we’ve been watching. They’ve been short-hopping their illicits out just to the edge of the system where others are picking it up and trading it on. We think certain interests in the Earth Company are supporting Mazian by running cargo for him, and that there’s a link between thefts and smuggling in Sol One district—not war materiel: luxury goods. Paintings. Foodstuffs. It’s high money. Money does buy Mazian what he wants.”

Among the captains, among four, there were a few exchanged glances and slow nods, sharp interest from the others.

“And Flare is no longer operating,” Joshua asked.

“Not Flare , but a ship named Jubal is. Was when we left Sol. Operating under Mallory’s close curiosity. We want to know where the goods are coming from, but we also have an interest in tracing the route through the black market, and figuring how it translates into supplies. We find it ironical that the primary market for illicit luxuries is Cyteen. And the second-largest is Pell. Every credit spent in the black market has a good chance of coming back as ammunition and supply for the Fleet. It’s picked up, run through the Hinder Stars, comes into this reach not necessarily at Mariner: more likely at Voyager, where security is less exacting, and then it travels on to Esperance, where it connects to Cyteen. But those are the heavy items. Big-time smuggling. In the same way, and adding up, money out of the whole shadow market is drifting into Mazian’s hands through the honest merchanters. People just like you and me. It’s a situation that can collapse stations. Collapse our markets. And have Mazian and Union going at it hammer and tongs again across Alliance routes. All of us will be fighting, if that happens, either that, or we’ll be hauling for Union trying to beat Mazian, and hoping to hell we don’t get hit by raiders the first voyage and the second and the third… That’s the situation we came from, and if we don’t get fairness out of the stations regarding our needs, and if we don’t get compliance out of our own brothers and sisters of the merchant Alliance to stop the trade that’s feeding Mazian, we’ll see the bad days back again and hell staring us in the face. You remember the feeling. You’ve been out in the dark, at some jump-point with a hostile on the scan and with no support in ten lightyears. Don’t leave Mallory in that condition. We’re decent people. Let’s stick to principles, here. Let’s realize how much the shadow-market does amount to, and who’s profiting.”

God, the Old Man could rivet the rest of them. And he could use words like principles , because he had them and acted by them. Nobody moved. JR thought, This is how it was all those years ago. This is how he got them to unite in the action that started the War.

“So what percentage are we talking about?” Lily Maid asked, to the point.

The Mariner stationmaster thought he was going to answer. The Old Man said:

“Pell’s talking ten.”

There was a slow intake of breath.

“No higher,” Lily Maid said, and Genevieve agreed.

“Are we talking about ten across the board?” the station-master wanted to know. “The luxury goods—”

“The point is,” the Old Man said, “voluntary compliance. We voluntarily confess the true manifest. If we install incentives to hedge the truth, if we need a rulebook to tell what’s right and wrong, there won’t be universal compliance. Flat ten.”

There were long sighs, frowns, shiftings of position, literal and maybe figurative. A junior witness to a major turn in human history didn’t dare take so much as a deep breath.

“It’s a talking point,” the stationmaster said “If Pell agrees on a universal ten. If the black market stops. If Union agrees on the same percentage.”

“We believe we can negotiate that point. They don’t want a resurgence of raids. And they’re worried about what’s getting onto the market. The luxury trade is sending biologicals right back down the pipeline, right to Earth. Surprisingly, Cyteen shares one thing with us: the belief that the motherworld, as our genetic wellspring, should be sacrosanct . In that regard, and in what it takes to cut Mazian off cold, we will have their cooperation. The fact that they may harbor notions of cutting harder deals after we eliminate Mazian as a threat means that we have two jobs to do, one of which is to strengthen, not weaken, our weakest and slowest ships. This proposal of ours answers both needs.”

They were listening. JR stood unmoving during discussion. He saw, from his vantage, Bucklin, who stood guard outside the meeting room, talking with Thomas B., who’d arrived with some news. Thomas B. left.

Then he saw Bucklin signal him, a fast set of hand-signals that said, in the way of spacers who sometimes worked in difficult environments, Talk, Urgent, Official.

He made his way around the edge of the room, and outside.

“Champlainers were in the Pioneer last watch,” Bucklin said. “And Champlain’s on the boards for depart in two hours. Alan just found it out.”

“God.”Their security was breached and the perpetrators were headed out toward a dark point of their next route. Armed and hostile perpetrators. “Where were they?”

“Came in with Belize . Spent the night and left this morning. Belize’s captain doesn’t know. They didn’t have access to the ID we got from customs.”

“Damn.” They’d used their military credentials to get official records on the Champlain and China Clipper crews. Belize couldn’t do that. And even knowing hadn’t enabled them to spot everybody that came and went, any more than they could go about warning other ships about ships that hadn’t committed any actual crime. “Just last watch, you’re sure.”

“Best I know, yes. Alan’s handling it. And they’re outbound; they went up on the boards in the last thirty minutes. Apparently it was two of the Champlainers, sleeping over with one Belize crew, on her invitation.”

“Some party.” He cast a look back through the glass where the meeting was still going on, still at a delicate point. It wasn’t a time to disturb the Old Man and Madison. It wasn’t a time to confront the Belize senior captain, who’d helped support their proposals, among others. “I suppose it’s too much to ask that the Belizer remembers exactly what he told them, or what they discussed.”

“She. And no, by what seems, she thinks there were two and she thinks they never left the room.”

Belize was a lively ship, say that for them.

“Can’t interrupt right now,” he said, “but five’ll get you ten we get an early board call. We might overjump that tub if we got moving. Let them stare down our guns.” He had his back to the windows to preclude lip-reading and didn’t want to create more distraction than his extended receipt of some message from Bucklin might have done already. “I’d better get back in there,” he said. “Nothing we can do from here. Where’s Tom gone?”

“Just passing the word about. Alan’s orders.”

“We’ll go on boarding call. Just watch.”

He went back into the meeting, took up a quiet, confident stance a little nearer the door.

Belize had had a particularly hard run from Tripoint, and a mechanical that had risked their lives getting in. To the Belize family’s delight, they’d sold their cargo right off the dock, the problem had turned out to be a relatively inexpensive module, and he had every sympathy for the Belizers’ desire to celebrate, in a sleepover far fancier than they ordinarily afforded. They’d lodged their juniors at the more junior-friendly Newton, and hadn’t remotely expected youngsters in a fancy lodging like the Pioneer. That was easily sorted out, and they weren’t bad people. The adult and randy Belizers, however, had proceeded to drink the bar dry, and gone down the row, looking for assignations the hour they’d docked—some of Finity ’s own had cheerfully taken them up on the offer. They’d been quieter neighbors since the first night, goodnaturedly gullible as they were, and now, damn! one of them had taken up with a ship their own captain had put the avoid sign on.