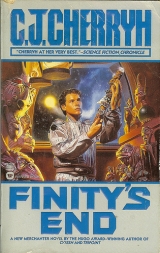

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

“We’ll get some,” Jeremy said as he watched the cart go. “Topside in the senior mess. There’s a get-together coming. Everybody’s there.”

“So?” he said. He wasn’t at all enthusiastic about meetings. He remembered board-call, and everybody together for that. It had been particularly uncomfortable. And he’d worked hard today. He thought he had a right to those desserts. “I’d rather read or something. Thanks.”

“You’re really supposed to go. It’s all of second and third shift, and a lot of first will come. That’s why they’ve been handing us fast food today. Eat light.”

“Is it a meeting, or what is it?”

“Not a meeting ,” Jeremy said as if he were a little slow. “Food. The fancy food. It’s a party . You know. People. Music. Party.”

“Why?”

“‘Cause that Union bunch is just sitting back there not bothering us, ’cause we’re in a big boring jump-point and we don’t have anything much to do. Why not ? When you’re downtimed and there’s no pirates going to bother you, you throw a party. Come on, Fletcher, you’ll enjoy it. Be loose. Jump before main-dawn, but tonight we shake things up, man. Be loose, be happy, it’s got to be somebody’s birthday! That’s what we say, it’s somebody’s birthday somewhere! Celebrate for George.”

“Who’s George?” There was such a thing as ship-speak: the in-jokes sometimes flew past him.

“King George V.”

He’d thought, with his fascination with old Earth history, there was no way a twelve-year-old from Finity was going to know King George of England. Or England, for that matter, in spite of Jeremy’s tape study. He was amazed. And enticed. “Why George?”

“Well, because he’s old and he’s dead, and nobody throws him parties anymore, so we do on Finity . When it’s nobody else’s birthday, it’s for old King George!”

He’d walked into that one. “Why not?” he said. “Seems logical.”

He still didn’t entirely want to go, but he considered the food they’d been working on all day; and he knew himself, that once he was committed to being alone, knowing full well there was a party going on elsewhere, he’d feel lonelier. I’d rather stay in my room and hate all of you might be the real answer, but it wasn’t, in Jeremy’s clear opinion, going to be the accepted answer.

Besides, Jeremy had, against all odds, made it sound like fun.

So they showered and put on clean, unfloured, unpeppered clothes without grease spots, and went up to B deck. Fletcher’s most dire apprehension in the affair was that he might have to suffer through some formal introduction of himself, standing up in front of people he didn’t want to be polite to. “They’re not going to introduce me again, are they?” he’d asked Jeremy. “I don’t want to be introduced.”

“They won’t if you don’t like,” Jeremy said. “I’ll tell them and they won’t.”

He still, riding up the lift to B deck, feared he couldn’t escape another round of j-names: John, James, Jerry and Jim . He was resigned to that idea, if not the idea of another introduction, or any sentimental This is Francesca’s baby on anybody’s part. As long as it stays George’s party, he’d told Jeremy, when he’d agreed. No surprises.

And when they walked up around the ring to the senior mess, he could see the food laid out, he could see tables spread with linen; and he could see people, the Family, all walking around or talking at random: no special recognition looked to be in the offing, no ceremony, no conspicuous embarrassment and no formality, either. The B deck rec hall turned out to be connected to the B deck mess hall, a wall-to-wall segment of the whole ring, carpeted, the area that was rec furnished with vid-game sets, not in use at the moment; a bar, which was in use; and maybe fifty tables with linen tablecloths like some high-class restaurant. The whole arrangement filled two segments of B deck’s ring, with only a little half-bulkhead and a drawn-back section door to separate rec from the mess. There were maybe a hundred, two hundred people—all, God save him, relatives—milling around in casual familiarity, with more arrivals coming in from either end of the area.

There was a pool table, a game going there, in the rec section. That had drawn a row of kibitzers. A couple of women played quiet, not-bad guitar in the background, up at the end of the mess hall, and the sweets and snacks from the mess hall were going fast. The bar opened up, and various mixed drinks and wine glasses ready to be picked up were going off the counter as fast as the kids serving could set them out, fifty, a hundred of them.

Held off on cheese sandwiches all day. Fletcher raided the dessert stack instead and filled his mouth with sweet cream pastry.

“Fletcher.”

He knew that voice. He turned and frowned at Madelaine. She had a glass of wine in hand and was clearly not official at the moment.

“Glad you came, Fletcher,” Madelaine said.

“Thanks,” he said, and knuckled a suspected smear of cream off his lip. He wouldn’t have come at all if he’d known he’d run into her first off.

“Enjoy things,” she said. And to his relief and gratitude, she didn’t engage him in intrusive, personal conversation, just smiled and walked past him, wine glass in hand, leaving him free to wander around with Jeremy.

Jeremy, who was bent on telling him who was who.

“No good with the names,” he said after six or seven. “There’s too many J’s in the lot. I’m not going to remember. Unless you can point out King George. Who is a G, isn’t he?”

Jeremy thought that was funny. “Everybody is J’s,” he said, as if he’d never added it up for himself. “Most, anyway. ’Cept you’re Fletcher. Probably the first Fletcher in fifty years.”

“Why? Why’s Fletcher the exception?”

“He was shot dead, a long time ago,” Jeremy said. “He was the one getting the hatch shut when the Company men were trying to board, and he did it and died on the deck inside. Or there wouldn’t be any of us. No Alliance. No Union.”

He knew about the incident. He’d learned it in school, but he didn’t know it was a Fletcher Neihart who’d been the one to get the door shut when they tried to trap Finity and arrest Captain James Robert. He knew about Finity’s End saying the Earth Company authorities weren’t going to board, and the captain and crew had sealed the ship and left the station and the authorities behind them, refusing them authority over the ship and refusing station law on a merchanter’s deck. It was where the first merchanter’s strike had started, when merchanters from one end of space to the other had made it clear that trade goods didn’t and wouldn’t move without merchant ships.

In a long chain of events, it was the incident that had started the whole Company War.

History. Near-modern history, which he detested. He’d passed the obligatory quiz on the details to get into the program. The Company War. Treaty of Pell, 2353, and that had left civilization where it was when he’d been born, with Union on one side and Alliance on the other and Earth not real happy with either of them. And him stranded and his mother dead. That kind of history.

So, Jeremy said, somebody he was named after had gotten a critical hatch shut in the original fracas between Company ships and Family ships, without which either the ship wouldn’t have gotten away or the cops who shot this long-dead Fletcher would have died in the decompression that would have resulted if he hadn’t shut that hatch.

Pell knew about that kind of event. And he’d known about the start of the Company War.

So the guy’s name had been Fletcher. He didn’t know why he should be proud of some spacer who was a hundred years dead—but, well, dammit, he’d lived all his seventeen years around the snobbery of the Velasquezes and the Willetts, the Dees and the Konstantins, who’d been important because of their names, and important mostly because of what dead people in their families had done, while he’d never before had a sense of connection to anything but an addict mother and a lawsuit.

Somebody died closing an airlock and did it with pieces of him shot away, knowing otherwise there’d be vacuum killing more than the people shooting at him—that was a levelheaded brave guy, in his way of thinking. While the Willetts—they’d donated a warehouse full of stuff to the war effort. Big deal. No one had been shooting at them.

And Fletcher Neihart meant that man, on this ship. Fletcher wasn’t just a name. It was a revision of who he was—for a moment.

He never had meant much. And that, he’d told himself when he’d been at a low point of his teenaged years, scared spitless of the program placement tests, that never meant much was the source of his strength: not giving much of a damn. Like a gyro—kick it off balance a second and it swung right back. That realization had kept him sane. Kept him aware of his own value, which was only to himself.

Maybe that was why Madelaine’s being here had upset him—why Madelaine had upset him and why even yet he was feeling shaky. He’d instinctively seen a danger when Madelaine had dangled the lure of his mother’s motives and his father’s name in front of him yesterday.

He’d been in danger a second ago when he’d thought about famous relatives.

He was in danger when he began to slip toward thinking… being Fletcher Neihart wasn’t that bad a thing.

Yes, and Jeremy wasn’t a bad kid, and they could get along, and maybe Jeremy could make this year of enforced servitude not so bad. But he’d thought he could rely on Bianca, too, and yesterday in the same conversation in which he’d learned he had a great-grandmother and the lawyers he hated really loved him, in the very same conversation Madelaine had proved Bianca had talked to authorities and betrayed everything he’d shared with her about Melody and Patch,

It was nothing to get that angry about. Bianca had behaved about average, for people he’d dealt with. Better than some. She hadn’t talked until she’d been cornered and until he’d already been caught and shipped off the planet,

So forget falling into the soft traps of potential relatives. Figure that Jeremy would keep some secrets and advise him out of trouble, but he shouldn’t get soppy over it or mistake it for anything special. Jeremy had his orders, and those orders came from authority just like Madelaine, if it wasn’t Madelaine herself. She wanted him to ask who his father was. He didn’t damn well care. Whoever it was hadn’t come to Pell. Hadn’t cared for him. Hadn’t cared for his mother.

Spacer mindset.

Safer just to disconnect from all of them, Jeremy too. He could be pleasant, but he didn’t have to commit and he didn’t have to trust any of them. And that meant he didn’t have to get mad, consequently, when they proved no better and no worse than anyone else. He’d learned that wisdom in his half a dozen family arrangements, half a dozen tries at being given the nicely prepared room, the nicely prepared brother, the family who thought they’d save him from his heritage and a mother who hadn’t been much.

In that awareness he walked in complete safety through the buzz of talk and the occasional hand snagging him to introduce him to this or that cousin… screw it, he thought: he wasn’t possibly going to remember anything beyond this evening. The names would sink in only over time and with the need to deal with one and another of them. If he really, truly needed to know Jack from Jamie B., he’d ask for an alphabetical list. In the meantime, everyone wore name tags.

He’d had a hard day, however, and what he did want to quiet his nerves and dim the day’s troubles wasn’t on the dessert tray. He strolled over to the bar, lifted a glass of wine, turned his shoulder before he had to deal with the bartenders and walked off with it, sipping a treat he hadn’t had at the Base but that he had had regularly in the latest family. The Wilsons had collected their subsidy from the station for taking care of him, he hadn’t caused them trouble (he’d been a model student who ate his meals out), he’d done his own laundry… fact had been, he’d boarded at the Wilsons’, and they were pleasant, decent folk who’d had him to formal dinners on holidays at home or in nice restaurants, and who hadn’t cared if he hit their liquor now and again as long as he cleaned up the bar and washed the glasses.

The wine tasted good. His nerves promised to unwind. He told himself to relax, smile, have a good time, get to know as many of the glut of relatives as seemed pleasant. Like Jeff. Jeff was all right. Even great-grandmother Madelaine was on an agenda of her own, nothing really to do with him as himself, except as the daughter-legacy Madelaine hoped he’d turn into. He would disappoint her, he was sure.

But if she refrained from exercising authority over him and just took him as he was, as she’d done when she’d failed to make a fuss over him here, he could refrain from resisting her. He could be pleasant. He’d been pleasant to a lot of people once he knew it was in his interest, as it seemed generally to be in his interest on this ship.

He’d like to find a few cousins who were somewhat above twelve years of age. He’d like to have someone to talk occasionally to whose passion wasn’t vid-games.

“God, you’re not supposed to have that,” Jeremy said, catching up to him.

“Had it on station.”

Jeremy was troubled by it. He saw that. But he had it now, and he wasn’t going to turn it in. He drank it in slow sips. He had no intention of gulping multiple glasses and making an ass of himself.

“What’s this?” He knew that young, high, penetrating voice, too. Vince had showed up, with Linda. Inevitably with Linda. “You can’t drink that.”

Vince and his holier-than-thou, wiser-than-everyone attitudes for what Vince wouldn’t dare do when he was taller and older. He gestured with the three-quarters full glass, “Have drunk it. When you grow up, you can give it a try. Meanwhile, relax.”

“You’ll get on report,” Vince said. “I’ll bet you get on report.”

“Fine. Let them ship me back. I’ll cry tears.”

“I wish they would,” Vince said, one of his moments of sincerity, and about that time a larger presence came up on him.

JR.

“He’s drinking,” Vince said as if JR had no eyes. Fletcher looked straight at JR.

“Somebody give you that?” JR asked in front of Jeremy and Vince and Linda. He’d had enough family togetherness for the day. He drank three-quarters of a well-hoarded glass down in three swallows.

“Here,” he said, and handed the empty glass to JR. JR almost let it fall. And caught it on the fly, not without spilling a couple of last drops to the expensive carpet.

Fletcher walked off. He’d had enough party and celebration, and beyond that, he wasn’t in a frame of mind to stay around to be discussed or reprimanded in front of his roommate, a twelve-year-old jerk, or a couple of hundred of his worst enemies. It was easy to leave in the open-ended mess hall section. He just kept walking to the lift, out where the light was dimmer and the noise was a lot less.

JR held a glass he didn’t want to be holding. He handed it to Vince, restraining himself from immediate comment. He didn’t know what exchange had preceded Vince’s complaint to him. Clearly cousin Fletcher had just overloaded on something, be it wine or family.

He refused to get into he-saids with immediately involved junior-juniors and walked to the bar to learn the plain facts. “Nate. Did you give Fletcher wine?”

Nate was one of the senior crew, now, lately of the junior crew, and Nate looked distressed. “No. He just took it. I didn’t know what to do. Has he got leave?”

“Not officially, no. You did right. You didn’t make an incident. Vince and the junior-juniors called him on it, though, and he flared and left.”

“The guy wasn’t real straightforward about asking for permissions, what it seems to me. I think he knew it was off limits.”

“Yeah. You and I both noticed. If he does it again just let him. I’ll talk to Legal and we’ll find out whether there were agreements with him before he boarded, or what.”

“Trouble?” Bucklin turned up by him at the bar, Bucklin couldn’t have missed Fletcher’s leaving.

“Vince sounded off about the drink. Fletcher’s pissed.”

“Cousin Fletcher came aboard pissed. Counting he was hauled here by the cops and the stationmaster, I’m not personally surprised he and young Vince should go critical. ”

“It’s on our watch,” JR sighed. “We got him, he’s ours.”

“Maybe we could have airlock drill,” Bucklin’s tone was wistful, the suggestion outrageous.

“I’m afraid that won’t solve it.” He couldn’t quite joke about it, tempest in an infinitesimal teacup though it might be. “Captain-sir wants him. Madelaine wants him. I’m afraid we ultimately have to work him in.”

“Between you and me only, this has a bad feeling.” This time Bucklin wasn’t making a joke at all. “This guy doesn’t want to be here. I mean, it’s hard enough to work him in if we wanted him. We’re busy. We’ve got nothing but unskilled labor in him. We had a fine thing going before we got lucky in the court, and I appreciate we had a legal problem, but—where are we going to fit him in?”

Bucklin left his complaint hanging after that, and after a moment, in his silence on the issue, Bucklin walked away. Bucklin wasn’t of a rank to say what was floating in the air unsaid. We don’t want him didn’t half sum up the feeling among the senior-juniors. They had had an integrated team that was turning their last-born batch of juniors, ending with Jeremy, into a tight-knit unit that would put the senior-juniors in crew posts in another couple of years, with Jeremy and Vince and Linda their best backup for what was going to be, with adequate luck, a sudden crop of babies forthcoming from this run. The senior-juniors were a team tested literally under fire. However thin they were in numbers, he saw the makings of a damned fine command in what his seniors had left him and what he’d spent the last seven years putting together. Supposing now that women did become pregnant, and that the nursery did acquire a new batch of kids, he and Bucklin and Lyra had plans to set Jeremy and Vince and Linda in charge of the ones who’d come out of the nursery as junior-juniors at just about the time that trio hit physical maturity. It had all been going to work out neatly, and then they got cousin Fletcher, of a physical size to fit with senior-juniors, basic knowledge far beneath that of junior-juniors, and a surly attitude to boot. Add to that a late-to-board-call stunt unprecedented in the history of the ship, for which Fletcher had proved nothing but self-righteous and angry.

It was wrong, the whole blown-out-of-proportion incident just now with the wine glass was just damned wrong , both what Fletcher had done walking out and what Vince had done lighting into him and what Jeremy had done standing confusedly in the middle. It wasn’t the drink. It was Fletcher’s attitude that made no way for anybody to back down; and as the saying went, it had happened on his watch.

On one level the Old Man didn’t want to know the details, the excuses, or the extenuating circumstances of the junior captain’s failures; on another level, the Old Man would rapidly know every detail that he knew the minute he walked in here and wanted to know where Fletcher was, and there was nothing worse in God’s wide universe than an interview with Captain James Robert Neihart, Sr. when your tally of mistakes went catastrophic—as it had just done in that little damn-you-all gesture of Fletcher’s.

He, supposed to handle things, had thought that in putting Fletcher with the junior-juniors he had arranged Fletcher a berth that wouldn’t expose his ignorance, put demands on his behavior, or burden his own essential and often working team with constantly babysitting Fletcher.

Yes, the senior crew including the Old Man had a load of personal guilt over cousin Francesca, over the fact they hadn’t made it back in time to prevent what they were relatively sure had been a suicide.

Yes, Francesca had named her kid one of the signal names in Finity ’s history, one of the names which, like James Robert , you didn’t just bestow on your kid without asking and without the bloodline to permit it.

Yes, Francesca had named him that name before she’d known she’d be left—she had done it, he guessed, not out of bitterness, or to imply a guilt they all felt, but to declare to a station who otherwise despised spacers that this was no common kid.

Unfortunately that name had stayed on after her suicide to confound Finity command, attached to a kid in the original Fletcher’s line, a kid caught in the wheels of jurisdiction and power games, a kid who by that name and Finity ’s reputation necessarily attracted attention in spacer circles.

And yes , James Robert had wanted to get a kid named Fletcher, his grand-nephew, out of the gears and out of station view. There’d be no shameful appendix to the life of the first Fletcher, to append his name to a kid hellbent—JR had seen the police reports—on conspicuous and public disaster, right down to his dive for the outback.

Yes, Francesca’s situation had been a tragedy. But a lot of people on Finity had had a lot harder situation than Francesca’s, in his estimation.

His mother was one, dead in the decompression. And Jeremy’s. And Vince’s half-brother. Or ask Bucklin, who’d lost every close relative in his whole line except Madison, and Madison, who’d lost everyone but Bucklin.

Damn right they were close, the ones left of the old juniors’ group, the ones like himself and Bucklin, who’d huddled together in nursery while the ship underwent stresses that killed the weak. They’d seen kids grow weaker and weaker until eventually they just didn’t come out of trank at a given jump.

Damned right they’d earned the pride they had and damned right they didn’t like all they’d won handed to a stranger on a platter, particularly when the stranger bitterly, insultingly rebuffed what welcome he was given.

He had a situation building, a resentment in his command. And it was his job to find a way to deal Fletcher in.

“So how is he?” Madison asked, second captain, and JR felt heat rise to his face, wondering what answer he possibly could find.

“He’s not happy.” To his left a guitar hit a quiet passage, strings ringing with a poignantly soft tune he’d heard since he was small; “Rise and Go.” Parting of lovers. Partings of every kind. It was cliché. It never failed to send the chills down his arms and the moisture to his eyes. It disturbed logic. Prompted frankness. “Neither are we with him, sir, plainly speaking, sir.”

“We had to take him,” Madison said. “This was our chance. We couldn’t leave him.”

“I’m aware of our obligation, sir. And mine. I’m not begging off from the problem, only advising senior command that I’ve not made significant headway with him.”

“Not only our obligation,” Madison said. “ Elene Quen had a part in this.”

That small, added information, so directly and purposefully delivered, struck him off balance. And at that moment Madelaine wandered over with a drink in hand.

“Jake’s called ops downside,” Madelaine said, “just to be sure, you know, that Fletcher made his quarters without incident.”

“I think he did,” JR said. The kid was angry. Not stupid. And if Madison’s information bore out into something besides Family determination to recover one of their own, there might be justification for that anger. Quen. Politics. Deals.

“He swiped a drink,” Madelaine said to Madison. “Pell Station let him, I’d be willing to bet. Station rules. He didn’t know he needed a go-ahead.”

Madison frowned. “The body’s old as JR, here. It’s the mind that’s under-aged. Your call, junior captain. What will you do with him?”

“My call,” JR said. “But this is a new one. Where do you rate him, sir? Junior-junior, or not? He’s Jeremy’s age and far less experienced.”

“ And physically the same as your age. Look up the statutory years.” Madison spotted someone coming in by the up-ring entry, and drifted off with that quandary posed, information half-delivered.

JR gazed after him in frustration. He drank, judiciously and seldom, and he had twenty-six years for mental ballast. He also had the responsibility for issuing such privileges to juniors under him. Was Madison saying give Fletcher senior-junior privileges right off? He didn’t think so.

And this hint of deals with Quen, that might have complicated the situation with understandings and arrangements… no one had told him.

“What’s this,” he asked Madelaine, “that the name of Quen came up just now? I know why we took him, on principle. He’s Fletcher . But what are we doing taking him in on this run, not asking for him after he’s local eighteen and the court’s off his case? Is there something essential that I’m not hearing, here?”

“Oh, there’s a fair amount you missed that night at dinner.”

“With Quen? What did I miss?”

“The fact Quen very ably moved the courts to give us Fletcher when she wanted to, after telling us for twelve years that she couldn’t budge them. Now, that may be an unfair suspicion. Possibly her position has changed: possibly she has more power now; perhaps she simply called in a tall stack of favors.” Madelaine stopped—he knew that silence of hers: she was suddenly wondering how much to tell the junior captain on a particular point, and a blurted question from him right now would make her sure he wasn’t qualified to know. So he stood quietly while Madelaine took a sip of wine and thought about her next piece of information.

“Quen wants a ship. She wants a Quen ship. And she wants James”—Madelaine was one of a handful who called the senior captain James and not James Robert —“to stand with her and get it approved.”

“That, I already know.”

“But it’s more than that. Like Mallory, Quen is worried about Union’s next moves. Thinks the next war is going to be a trade war. Union’s building ships it proposes to put into trade and saying they don’t violate the Treaty. We of course say differently. Fletcher’s an issue on his own and always has been, but he’s become an issue of trust between us and Quen. Quen proves to us she’s got power on Pell by delivering Fletcher to us, maneuvering past Pell’s red tape—and we’ll stand by her in the Council of Captains and use our considerable stack of favor-points with other ships to swing votes on the issue she wants—if she backs us. We want tariffs lowered. An unrelated understanding, mark that.”

He did. There was no linkage between the two events because both parties agreed there wasn’t a linkage. Yes, Finity could fail to carry out their part of the deal, take Quen’s gift of Fletcher and go on to oppose Quen in Council, because there wasn’t a linkage. But if Finity betrayed her, Quen wouldn’t be their ally on something else they wanted her vote on.

And what was there to deal for? Quen wanted a Quen ship: understandable. What was there that Finity would be wanting from Quen? Lower tariffs didn’t sound at all related to the battle they’d been fighting against Mazian. It affected merchanter profits and the price of goods. That was all that he saw.

Tariffs affected trade; trade affected international affairs. Did the question have any relation to that Union ship out there, the most notable anomaly in this voyage besides their own declaration they were going back to merchanting? Quen detested Union, so he’d heard. And Quen had traded them the kid they’d held hostage for seventeen years because now Quen wanted to build ships.

Build ships to keep Union from building ships to operate essentially on trade routes within Union. That was a delicate and sticky point: pre-War and post-War, all commercial trade routes in existence had been independent merchanter freighter routes—all, that was, except the two routes between Cyteen and its outermost starstations. On those two routes Union had always used its own military transport, in supply of, the merchanters were given to understand, fairly spartan stations, probably populated by Union’s tailor-made humanity, for what he knew. No merchanter in those days had been interested in going there. That mistake had given Union a foothold in merchanter operations.

“So…” he asked Madelaine, “what is going on? How did Fletcher get into it, besides as a bargaining chit? And why are we making deals with Quen? Or is that what we’re really doing on this voyage? Who are we fighting? Mazian? Or Union?”

“This is topside information,” Madelaine said, meaning what she told the junior first captain didn’t go to the junior-juniors or even to Bucklin. “We were always anxious to get Fletcher out. We didn’t expect to get Fletcher this round. We took him because we could take him. Quen happens to hold a general view of the situation with Union we want her to act on, but we don’t tell her that. We have to let her persuade us at great effort, or she’ll start arranging other deals with other parties because she’ll believe we folded too easy and we’re up to something. So Fletcher wasn’t at issue… we snatched him up because we could; we just didn’t plan on him becoming a high-profile problem on this voyage.”

Aside from the damage done his tight-knit command, he didn’t like the ethical shading of the transaction he was hearing about, for Madelaine’s own great-grandson. They were merchanters, and they bought and sold, but people shouldn’t fit into a category of goods. In that regard he felt sorry for anyone caught in the turbulence around their dealings, Mallory’s and Quen’s. And if Fletcher detected the nature of the dealings, it could certainly explain Fletcher’s state of mind.

“You’re not to tell that,” Madelaine said, extraneous to any prior understandings she’d elicited of him. Madelaine was drinking wine and maybe just a little bit more open than she’d have wanted to be. “Especially to Fletcher.”

“You don’t like Quen,” JR observed. It seemed to him that Quen was an unanswered question, and what her dealings had been were never clear.

“I don’t,” Madelaine said. “Not personally. I admire her. I don’t like her. She got personally involved with a stationer, kited off from Estelle because she was head over heels in love with a bright young station lawyer and nobody could prevent Elene doing any damn thing. It’s uncharitable to say it, but that’s the case. Elene was on station when her ship died because Elene was having her way in one of her romantical fancies. My Francesca was on station because she had no damn choice, medically speaking, and we had to transfer her off and go in fifteen minutes.” Another sip of wine. “Now Elene’s a hero of the Alliance and my granddaughter’s dead of an overdose. Quen didn’t do one thing to make her life easier while she was alive and alone there. Not one.”