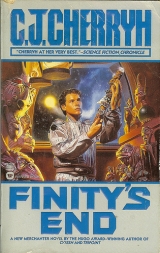

Текст книги "Finity's End "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 31 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

God, he knew this kid. So well.

“That’s why you were sick at your stomach the morning we left Mariner. That’s why you wanted to go back and look for something. Isn’t it?”

“I could get a couple of tapes. So you wouldn’t know I got robbed. And I didn’t know what to do…” Jeremy’s teeth were knocking together. “I didn’t want you to leave, Fletcher. I don’t ever want you to leave.”

“I’ll try,” he said. “Best I can do.” Third shake at Jeremy’s ankle. “Adult lesson, kid. Sometimes there’s no fix. You just pick up and go on. I’m pretty good at it. You are, too. So let’s do it. Forget the stick. But don’t entirely forget it, you know what I mean? You learn from it. You don’t get caught twice.”

And the Old Man’s voice came on. “ This is James Robert ,” it began, in the familiar way. And then the Old Man added…

“… This is the last time I’ll be speaking as a captain in charge on the bridge .”

“God.” Color fled Jeremy’s face. He looked as if he’d been hit in the stomach a second time. “God. What’s he say?”

It didn’t seem to need a translation. It was a pillar of Jeremy’s life that just, unexpectedly, quit.

It was two blows inside the same hour. And Fletcher sat and listened, knowing that he couldn’t half understand what it meant to people who’d spent all their lives on Finity .

He knew the Alliance itself was changed by what he was hearing. Irrevocably.

“… There comes a time, cousins, when the reflexes aren’t as sharp, and the energy is best saved for endeavors of purely administrative sort, where I trust I shall carry out my duties with your good will. I will, by common consent of the captains as now constituted, retain rank so far as the outside needs to know. I make this announcement at this particular time, ahead of jump rather than after it, because I consider this a rational decision, one best dealt with the distance we will all feel on the other side of jump—where, frankly, I plan to think of myself as retired from active administration.

“ I reached this personal and public decision as a surprise even to my fellow captains, on whose shoulders the immediate decisions now fall. From now on, look to Madison as captain of first shift, Alan, of second, and Francie, of third. Fourth shift is henceforth under the capable hand of James Robert, Jr., who’ll make his first flight in command today, the newest captain of Finity’s End.”

The bridge was so still the ventilation fans and, in JR’s personal perception, the beat of his own heart, were the only background noise. He watched as the Old Man finished his statement and handed the mike to Com 1, who rose from his chair.

Others rose. In JR’s personal memory there had never been such a mass diversion of attention—when for a handful of seconds only Helm was minding the ship.

There were handshakes, well-wishes. There were tear-tracks on no few faces. There was a rare embrace, Madison of the Old Man.

And the Old Man, among others, came to JR to offer a hand in official congratulation. The Old Man’s grip was dry and cool in the way of someone so old.

“Bucklin will sit hereafter as first observer,” the Old Man said. “Jamie. You’ve grown halfway to the name.”

“A long way to go, sir,” JR said. “I’ll pass that word, to Bucklin, sir. Thank you.”

The Old Man quietly turned and began to leave the bridge, then.

And stopped at the very last, and looked at all of them, an image that fractured in JR’s next, desperately withheld blink.

“I’ll be in my office,” the Old Man said gruffly. “Don’t expect otherwise.”

Then he walked on, and command passed. JR felt his hands cold and his voice unreliable.

“Carry on,” Madison said. “Alan?”

Third shift left their posts. Fourth moved to take their places.

His crew, now. Helm 4 was gray-haired Victoria Inez. She’d be there, competent, quiet, steady. Not their best combat pilot: that was Hans, Helm 1. But if you wanted the velvet touch, the finesse to put a leviathan flawlessly into dock, that was Vickie.

The other captains left the bridge. The little confusion of shift change gave way to silence, the congestion in JR’s throat cleared with the simple knowledge work had to be done.

JR walked to the command station, reached down and flicked the situation display to number one screen. “Helm,” he said as steadily as he had in him. “And Nav. Synch and stand by.”

“Yessir,” the twin acknowledgements came to him.

He looked at the displays, the assurance of a deep, still space in which the radiation of the point itself was the loudest presence, louder than the constant output of the stars. They could still read the signature of two ships that had passed here on the same track, noisy, making haste.

No shots had been fired. Champlain had wasted no time in ambush.

Boreale had wasted no time in pursuit. The action, whatever it was, was at Esperance.

Before now, he’d made his surmises merely second-guessing the captain on the bridge. Now he had to act on them.

“Armscomp.”

“Yessir.”

“Synch with Nav and Helm, likeliest exit point for Champlain . Weapons ready Red.”

“Yes, sir.”

He authorized what only two Alliance ships were entitled to do: Finity and Norway alone could legally enter an inhabited system with the arms board enabled.

“Nav, count will proceed at your ready.”

“Yessir.”

Switches moved, displays changed. Finity’s End prepared for eventualities.

He did one other thing. He contacted Charlie, in medical, and ordered a standby on the Old Man’s office. Charlie, and his portable kit, went to camp in the outer office.

It was the captain’s discretion, to order such a thing. And he ordered it before he gave the order that launched Finity’s End for jump, and gave Charlie time to move.

They needed the Old Man, needed him so badly at this one point that he would order medical measures he knew the Old Man would otherwise decline.

One more port. One more jump. One more exit into normal space. The Old Man was pushing it hard with the schedule they’d set. And they had to get him there.

Chapter 23

There was silence from the other bunk, in the waiting.

“Kid,” Fletcher said after long thought. “You hear me?”

“Yeah.” Earplugs were in. They were riding inertial, in this interminable waiting, and they could see each other. Jeremy pulled out the right one.

“I’ve had time to think. I shouldn’t have blamed you about Chad. I picked that fight. Down in the skin. I hit him.”

“Yeah,” Jeremy said.

“Not your fault. Should have hit Sue.”

“You can’t hit Sue.”

“Yeah, well, Sue knows it, too.”

“You want to get her? I can get her.”

“I want peace in this crew, is what I want. You copy?”

“ Stand by ,” the word came from the bridge.

“Yessir,” was the meek answer. “I copy.”

Engines cut in.

Bunks swung.

“He’s never done this before!” Jeremy said. “Kind of scary.”

He thought so, too, though as he understood the way ships worked, he didn’t imagine JR with his hands on the steering. Or whatever it was up there. Around there… around the ring from where they were.

“ Good luck to us all ,” came from the bridge. “ Here we go, cousins. Good wishes, new captain, sir. Good wishes, Captain James Robert, Senior. You’re forever in our hearts .”

“Amen,” Jeremy said fervently.

“Esperance,” Fletcher said. He’d looked for it months from now, not in this fervid rush.

But it was months on. It was three months going on four, since Mariner. Going on six months, since Pell.

It was autumn on Downbelow. It was coming on the season when he’d come down to the world.

It was harvest, and the females would be heavy with young and the males working hard to lay by food for the winter chill.

Half a year. And he was mere weeks older.

The ship lifted. Spread insubstantial wings…

Rain pattered on the ground, into puddles. Pebbles crunched and feet splashed in shallow water as they carried him, as Fletcher stared at a rain-pocked gray sky through the mask.

He knew he was in trouble, despite the people fussing over his health. They’d rescued him, but they wanted him out of their program. They were glad he was alive, but they were angry. Was that a surprise?

They carried him into the domes and took the mask off and his clean-suit off, the safety officer questioning him very closely about whether he’d breached a seal out there.

If he’d had his wits about him he’d have said yes and let them think he’d die, and that alone would prevent him being shipped anywhere, but he stupidly answered the truth and took away his best chance, not realizing it until he’d answered the question.

They’d found the stick, too, and they wanted to take that from him before he got into the domes, but he wouldn’t turn it loose. “Satin gave it to me,” he said, and when they, like his rescuers, suggested he was crazy and hallucinating, he roused enough to describe where he’d been: that he’d talked to the foremost hisa, and the one, the rumor said, who could get hisa either to work or not to work with humans, plain and simple. The experts and the administrators, who’d suited to come out and meet them coming in, pulled off a little distance in the heavily falling rain and talked about it, not quite in his hearing. They’d given him some drug. He wasn’t sure what. He wasn’t even sure when. Four of the rescuers had to hold him on a stretcher while the experts conferred, and he supposed they were frustrated. They shifted grips several times.

But then someone from the medical staff came outside, suited up too, for the purpose; and the doctor encouraged him to get on his feet, so that he could go through decon, with people holding him.

They wanted to put the stick through the irradiation, and that was all right: he took it back, after that, and wobbled out, stick and all, into a warm wrap an officer held waiting for him.

Then they let him sit down and checked him over, pulse, temperature, everything his rescuers had already done; and another set of medics went over those reports.

After that, when he was so faint from hunger his head was spinning, they gave him hot soup to drink, and put him to bed.

Nunn showed up meanwhile and gave him a stern lecture. He was less than attentive, while he had the first food he’d had in days. He gathered that he’d caused Nunn trouble with Quen, and that Nunn now found fault with most everything he’d ever done in classes. He didn’t see how one equated with the other, but somehow Quen’s directives had overpowered everything but the medical staff. He got sick, couldn’t keep the soup down; and Nunn left, that was the one good thing in a bad moment. He had to go to bed, then, and they gave him an IV and let him go to sleep.

But when he waked, the science office sent people with recorders and cameras who kept him talking for hours after that, wanting every detail. He slept a great deal. He’d run off five kilos, the doctor said, and he was dehydrated despite being out in the rain for days. It was an endless succession of medical tests and interviewers.

Last of all Bianca came.

He’d been asleep. And waked up and saw her.

“How are you feeling?” she asked him.

“Oh, pretty good,” he said. “They bother you?”

“No. Not really.”

“They’re shipping me up,” he said. “I guess you heard. My family wants me back. On Finity’s End .”

“Yes,” she said “They told me.”

“You’re not in trouble, are you?”

She shook her head.

And she cried.

He was incredibly dizzy. Drugged, he was sure, sedated so his head spun when he lifted his head from the pillow. He fought it. He angrily shoved himself up on one arm and tried to get up, tried to fight the sedative.

And almost fell out of bed as his hand hit the edge.

“Don’t,” Bianca said. “Don’t. I’ve only got a few minutes. They won’t let me stay.”

She leaned over and kissed him then, a long, long kiss, first they’d ever shared. Only time they’d ever been together, except in class, without the masks.

“I’ll get back down here,” he said. “I’ll get off that damn ship. Maybe they’ll put me in for a psych-over and I won’t have to go with them.”

“Velasquez.” A supervisor had come to the door. “Time’s up.”

She hugged him close.

“Velasquez. He’s in quarantine.”

“I’ll get back,” he said.

“I’ll be here,” she said. Meanwhile the supervisor had come into the flimsy little compartment to bring her out; and Bianca just moved away, holding his hand as long as she could until their fingers parted.

He fell back and it was a drugged slide into a personal dark in which Bianca’s presence was like a dream, one before, not after the deep forest and the downer racing ahead of him.

The plain was next. A golden plain of grass, with the watchers endlessly staring into the heavens…

Not there any longer. Never there.

Esperance was where. Esperance.

“Jeremy?” He missed the noise from that quarter. Jeremy was very quiet.

“Yeah,” he heard finally. “Yeah. I’m awake.”

“We’re there. You drink the packets?”

“Trying,” Jeremy said. And scrambled out of his bunk and ran for the bathroom.

Jeremy was sick at his stomach. Light body, Fletcher said to himself, and drank a nutri-pack, trying to get his own stomach calmed.

Esperance. Their turn-around point. Midway on their journey.

Chapter 24

Boreale was a day from docking. Champlain was just coming into final approach, an hour from dock.

JR looked at the information while he drank down the nutrient pack and assessed damage. There was one piece of information he wanted, and it was delayed, pending. Charlie would check on the Old Man. Meanwhile he knew his two problems were there ahead of him, but not that much ahead, not so far ahead that they could have made extensive arrangements.

He meditated ordering a high-speed run-in that would put them at dock not long after the two ships in question.

It would also focus intense attention on them, at all levels of Esperance structure, and might impinge on negotiations to come. Foul up the Old Man’s job and he’d hear about it.

He ordered the first and second V- dump, which removed that possibility—and followed approach regulations for a major starstation.

Please God the Old Man was all right. He got down another nutri-pack.

A message from Charlie came through, welcome and feared at once. “ He’s complaining ,” Charlie said. “ Says he’s getting dressed. Madison says he should stay put .”

He gave a little laugh, he, sitting on the bridge and waiting for Alan to relieve him. Their plans had them saving first and second shift in reserve throughout the run-in. Third and fourth were going to work in that edge-of-waking way bridge crew sat ready during jump, and Vickie was going to be at Helm on dock. That meant long shifts, but it also meant the Old Man was going to get maximum rest during their approach.

So would Madison, whose feelings in this shift of personnel were also involved. Madison had gone on the protected list right along with the Old Man, and while Madison hadn’t quite complained about Alan’s and Francie’s ganging up to take all those shifts, Madison hadn’t realized officially that he was being coddled.

“Tell the Old Man there’s not a pan in the galley out of place, and Boreale will be thinking about our presence on her tail as a major Alliance caution flag. She won’t innovate policy. Isn’t that the rule?”

“ Don’t quote me my own advisements !” the Old Man’s voice broke in: that com-panel on his desk reached anything it wanted to. Of course the Old Man had been shadowing his decisions.

Then, quietly, “ Not a pan out of place, indeed, Jamie. Good job .”

“Thank you, captain, sir,” JR said calmly, then advised Com 2 to activate the intercom, because it was time. The live intercom blinked an advisory Channel 1 in the corner of his screen.

“The ship is stable,” he began then, the age-old advisory of things rightfully in their places and the ship on course for a peaceful several days.

Routine settled over the ship. Fletcher would never have credited how comforting that could feel—just the routine of meals in the galley, and himself and the junior-juniors stuck with a modified laundry-duty, a stack they couldn’t hope to work their way through in the four days, while senior-juniors drew the draining and cleaning of spoiled tanks in Jake’s domain—not an enviable assignment. Meanwhile the flash-clean was going at a steady rate, since they had the senior-seniors’ dress uniforms on priority for meetings that meant the future of the Alliance and a diminution of Mazian’s options.

He’d never imagined that a button-push on a laundry machine could be important to war and peace in the universe, but it was the personal determination of the junior-junior crew that their captains were going into those all-important station conferences in immaculate, impressive dress.

They had to run up to A deck to collect senior laundry: all of A deck was so busy with clean-up after their run that senior staff had no time for personal jobs. Linda and Vince did most of the errands: Jeremy for his part wanted to stay in the working part of the laundry and not work the counter.

“No,” Fletcher said to that idea. “You go out there, you work, you smile, you say hello, you behave as your charming self and you don’t flinch.”

“They think I’m a jerk!” Jeremy protested.

“We know you’re not. You know you’re not. Get out there, meet people, and look as if you aren’t.”

Jeremy wasn’t happy. Sue and Connor showed up to check in bed linen, the one item they were running for the crew as a whole, and Jeremy ducked the encounter.

Fletcher went out and checked the cousins off their list, and Jeremy showed up after they were gone.

“You can’t do that,” Fletcher said. “You can’t flinch. Yes, you’re on the outs. I’ve been on the outs. They’ve been on the outs. It happens. People get over it if you don’t look like a target.”

“They’re all talking about me.”

“Probably they’re talking about their upcoming liberty, if you want the honest truth. Don’t flinch . They forget, and it was an accident, for God’s sake. It wasn’t like you stole it.”

Jeremy moped off to the area with the machines, a maneuver, Fletcher said to himself in some annoyance, to have him doing the consoling, when, no, it wasn’t a theft, and, no, losing it wasn’t entirely Jeremy’s fault.

Irreplaceable, in the one sense, that it was from Satin’s hand; but entirely replaceable, in another. He’d begun to understand what the stick was worth—which he suspected now was absolutely nothing at all, in Satin’s mind: the stick was as replaceable as everything else downers made. You lost it? she would say– any downer would say, in a world full of sticks and stones and feathers. I find more, Melody would say.

No downer would have fought over it, that was the truth he finally, belatedly, remembered. Fighting was a human decision, to protect what was a human memory, a human value set on Satin’s gift. It was certain Satin herself never would fight over it, nor had ever meant contention and anger to be a part of her gift to him.

In that single thought—he had everything she was. He had everything Melody and Patch were.

And he suddenly had answers, in this strange moment standing in a ship’s laundry, for why he’d not been able to stay there, forever dreaming dreams with downers. Satin had sent him back to the sky, and into a human heaven where human reasons operated. She might not know why someone in some sleepover would steal her gift, but a downer would be dismayed and bewildered that humans fought over it.

But—but—this was the one downer who’d gone to space, who’d set her stamp on the whole current arrangement of hisa and human affairs. This was the downer who’d dealt with researchers and administrators and Elene Quen. She knew the environment she sent him to. She’d seen war, and been appalled.

So maybe she wouldn’t be as surprised as he thought that it had come to fighting.

Maybe, he thought, that evening in the mess hall, when he and Jeremy were in line ahead of Chad and Connor, maybe humans had to fight. It might be as human a behavior as a walk in spring was a downer one. It might be human process, to fight until, like Jeremy, like him, like Chad, they just wore out their resentments and found themselves exhausted.

So he’d only done what other humans did. But a human who knew downers never should have fought over Satin’s gift. He most of all should have known better—and hadn’t refrained. It certainly proved one point Satin had made to him—that he really was a wretched downer, and that he was bound to be the human he was born to be, sooner or later.

And it showed him something else, too. Downers left the spirit sticks at points of remembrance, at Watcher-sites, on graves. Rain washed them, and time destroyed them—and downers, he now remembered, didn’t feel a need to renew the old ones. So they weren’t ever designed to be permanent. He had the sudden notion if he were bringing one to Satin, he could make one of a metal rod, a handful of gaudy, stupid station-pins, and a little nylon cord. She’d think it represented humans very well, and that it was, indeed, a human memory, persistent as the steel humans used.

In his mind’s eye he could imagine her taking it very solemnly at such a meeting, very respecting of his gift. He imagined her setting it in the earth at the foot of Mana-tari-so, and he imagined it enduring the rains as long as a steel rod could stand. Downers would see it, and those who remembered would remember, and as long as some remembered, they would teach. That was all it was. It was a memory. Just a memory.

And no one could ever steal that, or harm it.

No one but him.

He’d been wrong in everything he’d done. He’d waked up knowing the simple truth this time, but he’d still been too blind to see it. He’d felt Bianca’s kiss, it was so real. And that had been sweet, and sad, and human, so distracting he hadn’t been thinking about hisa memories. And that was an answer in itself.

Silly Fetcher, he heard Melody say to him. He knew now what he was too smart to know before, when he’d set all the value on physical wood and stone.

Silly Fetcher, he could hear Melody say to him. Silly you.

He sleepwalked his way through the line, ended up setting his tray beside Vince’s, with Jeremy setting his down, too, across from him.

Chad and Connor were just at the hot table at the moment. Maybe it wasn’t the smartest thing, remembering keenly that he wasn’t a downer and that those he dealt with weren’t—but he waited until he saw Chad and Connor sit near Nike and Ashley.

Then, to Jeremy’s, “Where are you going, Fletcher?” he got up, left his tray, and went over two rows of tables.

He sat down opposite Chad, next to Connor. “I owe you an apology,” he said, “from way before the stick disappeared. I took things wrong. That doesn’t require you to say anything, or do anything, but I’m saying in front of Connor here and the rest of the family, I’m sorry, shouldn’t have done that, I overreacted. You were justified and I was wrong. I said it the far side of jump, and I’m still of that opinion. That’s all.”

Chad stared at him. Chad had a square, unexpressive face. It was easy to take it for sullen. Chad didn’t change at all, or encourage any further word. So he got up and left and went back to the table with Vince and Linda and Jeremy.

“What’d you say to him?” Jeremy wanted to know.

It was daunting, to have a pack of twelve-year-olds hanging on your moves. But some things they needed to see happen in order to know they ought to happen among reasonable adults. “I apologized,” he said.

“What’d he say?” Linda wanted to know.

“He didn’t say anything. But he heard me. People who heard me accuse him heard it. That’s what counts.”

Jeremy had a glum look.

“Chad’s an ass,” Vince said.

“Well, I was another,” Fletcher said. “We can all be asses now and again. Just so we don’t make a career of it.—Cheer up. Think about liberty. Think about cheerful things, like going to the local sights. Like going to a tape shop. Getting some more tapes.”

“My others got stolen,” Jeremy said in a dark tone.

“Well, don’t we have money coming?”

“We might,” Vince said. “They said we were supposed to have some every liberty. And we didn’t get anything at Voyager.”

“Ask JR,” Linda said. “He’s a captain now.”

“I might do that,” Fletcher said.

But Jeremy didn’t rise to the mood. He just ate his supper.

That evening in rec he lost to Linda at vid-games, twice.

Won one, and then Jeremy decided to go back to the cabin and go to sleep.

That was a problem, Fletcher said to himself. That was a real problem. He was beginning to get mad about it.

“Am I supposed to entertain you every second, or what?” he asked Jeremy when he trailed him back. He caught him sitting on his bunk, and stood over him, deliberately looming. “I’ve done my best!”

“I’m not in a good mood, all right?”

“Fine. Fine! First you lose the stick and now I’m supposed to cheer you up about it, and every time I try, you sulk. I don’t know what game we’re playing here, but I could get tired of it just real soon.”

“Why don’t you?”

“Why don’t I what?”

“Go bunk by yourself. I was by myself before. I can be, again. Screw it!”

“Oh, now it’s broken and we don’t want it anymore. You’re being a spoiled brat, Jeremy. You owe me, but you want me to make it all right for you. Well, screw that ! I’m staying.”

Jeremy had a teary-eyed look worked up—and looked at him as if he’d grown two heads.

“Why?”

“Because, that’s why! Because! I live here!”

Jeremy didn’t say anything as Fletcher went to his bunk and threw himself down to sit. And stare.

“I didn’t mean to do it,” Jeremy muttered.

“Yeah, you mentioned that. Fact is, you didn’t do it, some skuz at Mariner did it. So forget it! I’m trying to forget it, the whole ship is trying to forget it and you won’t let anybody try another topic. You’re being a bore, Jeremy.—Want to play cards?”

“No.”

Fletcher got out the deck anyway. “I figure losing the stick is at least a hundred hours. You better win it back.”

Resignation: “So I owe you a hundred hours.”

“Yeah, and Linda beat you twice tonight, because you gave up. Give up again ? Is this the guy I moved in with? Is this the guy who wants to be Helm 1 someday?”

“No.” Jeremy squirmed to the edge of his bunk, in reach of the cards. Fletcher switched bunks, and dealt.

Jeremy beat him. It wasn’t quite contrived, but it was extremely convenient that it turned out that way.

Esperance Station—a prosperous station, in its huge size, its traffic of skimmers and tenders about a fair number of ships at dock.

Among which, count Boreale , which had sent them no message, and Champlain , which had sat at dock for days during their slow approach, and because of which, yesterday during the dog watch of alterday, Esperance Legal Affairs had sent them notification of legal action pending against them.

Champlain was suing them and suing Boreale , claiming harassment and threats.

Handling the approach to Esperance docking as the captain of the watch, JR reviewed the list of ships in dock. There were twenty ships, of which three were Union, two smaller ships and Boreale; five were Unionside merchanters… ships signatory to Union, and registered with Union ports. All were Family ships, still, and four of them, Gray Lady, Chelsea, Ming Tien , and Scottish Rose , had chosen to believe Union’s promise that their status would never change: they were honest merchanters who’d simply found Union offers of lower tariffs and safe ports attractive and who’d believed Union’s promise of continued tolerance of private ownership of their ships. JR personally didn’t believe it; nor did most merchanters in space, but some had believed it, and some merchanters had been working across the Line from before the War and considered Union ports their home ports.

Those four ships were no problem. Neither were the three Union ships. They had no vote. Union would dictate to them.

But the fifth of the Unionside merchanters, Wayfarer , was a ship working for the Alliance while under Union papers: a spy, no less, no more, and they had to be careful not to betray that fact.

There was, of course, Champlain , also a spy, but on Mazian’s side—unless it was by remote chance Union’s; or even, and least likely, Earth’s—that was number eight.

Nine through eighteen were small Alliance traders, limited in scope: Lightrunner, Celestial, Royal, Queen of Sheba , and Cairo; Southern Cross, St. Joseph, Amazonia, Brunswick Belle , and Gazelle . Nineteen and twenty were Andromeda and Santo Domingo , long-haulers, plying the run between Pell and Esperance, and on to Earth. Those two were natural allies, and a piece of luck, at a station where they already had a charge pending from a hostile ship, not to mention a hostile administration.

Those two had likely been carrying luxury goods, having the reach to have been at ports where they could obtain them; and they would be a little glad, perhaps, that they’d sold their cargoes before Finity ’s cargo hit the market, as that cargo was doing now, electronically. Madison was in charge of market-tracking.

“Final rotation,” Helm announced calmly. They were on course toward a mathematically precise touch at a moving station rim.

“Proceed,” JR said, committing them to Helm’s judgment. They were going in. Lawyers with papers would be waiting on the dockside. Madelaine had papers prepared as well, countersuing Champlain for legal harassment.

Welcome, JR thought, to the captaincy and its responsibilities. He hadn’t asked the other captains whether to launch a counter-suit. He simply knew they didn’t accept such things tamely, he’d called Madelaine, found that she’d already been composing the papers; and the Old Man hadn’t stepped in.

He didn’t go, this time, to take his place in the rowdy gathering of cousins awaiting the docking touch in the assembly area. Bucklin would be there. Bucklin would be in charge of the assembly area setup before dock and its breakdown after, and Bucklin would be overseeing all the things that he’d overseen.

That meant Bucklin wouldn’t be at his ear with commentary, or the usual jokes, or sympathy, even when Bucklin found free time enough to be up here shadowing command. Bucklin wouldn’t observe him for instruction, not generally. Bucklin would concentrate his observation on Madison, ideally, and learn from the best.