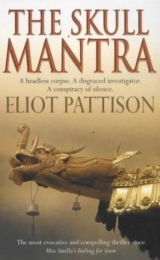

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"How far?"

"Into his cycle. Saskya gompa is orthodox. They would follow the old rules. Three, three, three is the usual cycle."

Shan let himself be pulled to the cell door. "Three?"

"The canonic cycle. Complete silence for three years, three months, three days."

"He speaks to no one?"

Yeshe shrugged. "The gompa would have its own protocol. Sometimes it is arranged that the abbot, or another esteemed lama, may communicate with a tsampsa."

Sungpo was looking beyond the wall again. Shan was not sure the accused murderer had even seen them.

Chapter Six

While the southern claws of the Dragon had not yet been tamed, their northern counterparts had been contained by a rough gravel road along their perimeter. Sergeant Feng drove along it fretfully, cursing the rocks that occasionally blocked the road, pausing to puzzle over the map despite the fact that before embarking he had laid out their route in red ink as if he were conducting a military convoy. At first he had ordered Yeshe to sit beside him with the map, with Shan at the door, then after ten miles stopped and ordered them out. He considered the seats as though they offered many confusing alternatives, then brightened. With a victorious grunt he moved his holster to his left hip and ordered Shan into the middle.

Shan ravenously consumed the map. The few times he had left the valley during the past three years had been in closed prison transports, exposing him to parts of the neighboring geography in a disjointed fashion, as if they were pieces of an unexplained puzzle. Quickly he tied the pieces together, finding the worksite on the South Claw where Jao had been killed, then the cave where his head had been deposited. Finally he traced their route through the mountains, circuiting one ridge until they nearly intersected the deep gorge that separated the North and South Claws, then looping west to circuit another ridge before dumping onto a small, high plateau labeled by hand in black ink. Mei guo ren, was all it said. Americans.

As Feng eased the truck to a stop to clear more rocks, Shan discovered they were beside the central gorge, known by the Tibetans as the Dragon's Throat. Centuries earlier a rock slide had tumbled into the Throat from this spot, leaving a small gap that dipped down toward the gorge, exposing an open view of the South Claw. There was a small annotation on the map– three dots arranged in a triangle. Ruins. It was an all-encompassing term. It could mean a cemetery, a gompa, a shrine, a college. A path rose up the short slope of the rock-fall and disappeared toward the chasm. Shan began to help Feng with the rocks, then paused and jogged up the path.

The ruin was a bridge, one of the spectacular rope suspension bridges that been constructed in a prior century by monk engineers who laid out civil works according to pilgrimage paths. It was battered but not destroyed. The path that led to the bridge, and away from it on the far side, appeared to be well traveled. Nearly a mile away Shan spotted a small patch of red, conspicuous in the dried heather of the steep slope.

"Should be there in thirty minutes," Feng said as Shan returned to the truck. He started the engine, then barked in protest as Shan grabbed a pair of binoculars from the back seat and moved back up the path.

He was still focusing on the red patch when Yeshe spoke at his shoulder. "A pilgrim."

Instantly Shan saw that Yeshe was correct. Although the distance was too great, he fancied that he heard the clump of wooden hand and knee blocks on the ground as the man kneeled, prostrated himself, and touched his forehead to the ground. Every devout Buddhist tried to make a pilgrimage to each of the five sacred mountains in his or her lifetime. When they traveled by the 404th, the prisoners would break discipline to call out a quick word of encouragement or snippet of prayer. Sometimes a man or a woman would take a year off just for such a pilgrimage. By bus one could travel from Lhasa to the most sacred peak, Mt. Kailas, in twelve hours. For the prostrating pilgrim it could take four months.

Sergeant Feng appeared. "The Americans! We are supposed to go to the Americans."

"I am going across to the crest of the ridge on the other side," Shan said.

Feng put his hand to his forehead as though suddenly in great pain. "You can't cross over," he growled. He grabbed the map, then brightened. "Look for yourself," he said with a triumphant grin. "It doesn't exist." Years earlier Beijing had condemned all the old suspension bridges. Most, because they eased the movement of resistance fighters, had been bombed by the People's Air Force.

"Fine," Shan said. "I am going to walk across this imaginary bridge. You stay here and imagine I am right beside you."

Feng's round face clouded. "The colonel didn't say anything about this," he muttered.

"And your duty is to assist me in the investigation."

"My duty is to guard a prisoner."

"Then let's return. We will ask Colonel Tan to clarify his orders. Surely the colonel would forgive a soldier who was confused by his orders."

Sergeant Feng looked to the truck in confusion. But Yeshe's expression was one of impatience. He took a step toward the vehicle, as though anxious to move on. "I know the colonel," the sergeant said uncertainly. "We served together a long time, before Tibet. He arranged my transfer when I asked to come to his district."

"Hear me, Sergeant. This is not a military exercise. This is an investigation. Investigators discover and react. I have discovered this bridge. Now I will react. From the crest of that ridge I think I will see the 404th worksite. I need to know if it is possible for someone to have climbed down, if there is a route other than the road." Climbed down, Shan thought, and climbed back up, carrying a human head. From where they stood the skull shrine was perhaps an hour's walk, and only a few minutes' drive.

Feng sighed. He made a show of checking the ammunition in his pistol, tightened his belt, and started toward the bridge. Yeshe moved even more reluctantly than Feng.

"You can never help him, you know," Yeshe said to Shan's back.

Shan turned. "Help him?"

"Sungpo. I know what you think. That you must help him."

"If he is guilty let the evidence show it. If he is innocent, doesn't he deserve our help?"

"You don't care because you don't mind being hurt. All you can do is get the rest of us hurt. You know you can't save someone who's already formally accused."

"Who are you trying to be? A little bird looking for a chance to sing to the Bureau? Is that what you live for?"

Yeshe stared at him resentfully. "I am trying to survive," he said stiffly. "Like anyone else."

"Then it's all been a waste. Your education. Your gompa training. Your detention."

"I have a job. I am going to get permits. I am going to the city. There's a place for everyone in the socialist order," he said with a hollow tone.

"There's always a place for people like you. China is filled with them," Shan snapped and pulled away.

Feng was already at the bridge, trying not to show his fear. "It's not– we can't-" He didn't finish the sentence. He was staring at the frayed ropes that held the span, the missing foot-boards, the swaying of the flimsy structure in the wind.

There was a cairn of rocks nearly six feet high at the foot of the bridge. "An offering," Shan suggested. "Travelers make an offering first." He plucked a stone from the slope, placed it on the cairn, and stepped onto the bridge. Feng looked toward the road as though to confirm there were no witnesses, then hastily found his own stone and placed it on the cairn.

The boards creaked. The rope groaned. The wind blasted down through the funnel of the Throat. Three hundred feet below, a trickle of water flowed through jagged rocks. Shan had to will his feet forward with each step, force his hands to relinquish their white-knuckle grip on the guide ropes to find their next purchase.

He stopped at the center, surprised to find a clear view of the new highway bridge, Tan's proud achievement, where the Throat emptied into the valley. The wind tore at his clothes and pushed at the bridge, giving it an unsettling rocking motion. He looked back. Feng was shouting, his words lost in the wind. He was gesturing for Shan to continue, not trusting the bridge with the weight of two men. Yeshe stood where Shan had left him, staring into the ravine.

On the other side of the gorge they walked up the steep slope for twenty minutes, with Shan in the lead as Sergeant Feng, older and much heavier, struggled to keep up. Finally the sergeant called out. When Shan looked back the pistol was out. "If you run, I'll come for you," Feng wheezed. "Everyone will come for you." He pointed the pistol at Shan but then quickly withdrew it with a startled look, as if the movement scared him. "They will bring your tattoo back," he said between gasps. "That's all they need. The tattoo." He seemed paralyzed with indecision. He gestured with the pistol. "Come here."

Shan moved slowly to his side, bracing himself.

Feng pulled the binoculars from Shan's neck and began moving back down the slope.

Shan surveyed the long slope of the ridge to the south. The patch of red that was the pilgrim was nearly out of sight. Above him, over the ridge, would be the 404th. He kept climbing. As he reached the top of the ridge Shan felt a surprising exhilaration, a feeling so unfamiliar he sat on a rock to consider it. It wasn't just satisfaction from his discovery of another route to the worksite, which was in plain view below. It wasn't just the awesome top-of-the-world view that stretched so far he could glimpse the shimmering white cap of Chomolungma, highest mountain of the Himalayas, more than a hundred miles away. It was the clarity.

For a moment it seemed he had not only reached the top, but entered a new dimension. The sky wasn't just clear, it was like a lens, making everything seem larger and more detailed than before. The clutter in his mind seemed to have been stripped away by the wind. His hand reached back and touched the spot where the lock of hair had been clipped. Choje would have said he was storming the gates of Buddhahood.

And then he realized: It was all because of the mountain. Jao could have been killed anywhere, certainly anywhere on the remote highway to the airport. He had been lured to the South Claw because someone wanted a jungpo to protect the mountain. Someone wanted to stop the road. Many had motives to kill Jao. But who had a motive to save the mountain? Or to stop the immigrants who would colonize the valley beyond? Jao had been with someone he knew and trusted. Those he knew and trusted would be interested in building, not blocking roads. The murder had an air of violent passion, yet obviously the killer had painstakingly planned his act. It was as if there were two crimes, two motives, two killers.

He unconsciously ran his fingers over his calluses. They were already getting soft, after just a few days. The hard shell of the prisoner was wearing away, which scared him, for he would need an even thicker one when he returned. His eyes wandered back to the 404th. The prisoners were on the slope. And below them, deployed at the bridgehead, was something new. The grim gray hulks of two tanks and the troop carriers used by the knobs. The prisoners were not working. They were waiting. The knobs were waiting. Rinpoche was waiting. Sungpo was waiting. And now he was waiting. All because of the mountain.

But he couldn't wait. If he did nothing but wait, Tan would devour Sungpo. And the knobs would devour the 404th.

He followed the crest back to its abrupt dropoff into the Dragon's Throat. But the dropoff wasn't totally vertical. A steep narrow path, a goat path, led down in a series of switchbacks to a jumble of rock slabs a hundred yards below. Slowly, risking a fall to his death with any misstep, Shan moved down the path to the rocks. They had sheared off the mountain and collected on a small ledge, creating a barrier from the wind.

He climbed out onto a large flat slab and found himself looking directly at the new Dragon's Throat Bridge, close enough to hear the rumble of the diesel engines that had been kept running in the tanks, and even snippets of conversation from the guards on the slope.

Fearful of being seen, he began to push back when he suddenly noticed chalk markings on the slab. It was Tibetan script and Buddhist symbols, but unlike any he had ever seen. He copied them into his pad and stepped between two slabs which had fallen together in an inverted V to create a shelter. He froze. In the back of the enclosure a circular picture had been painted on the stone, an intricate mandala which had required many hours of work. In front of it was a row of small ceramic pots such as those used for butter lamps. They were all broken. But they had not been broken casually. They had been arranged in a row and broken where they stood, as if in a ritual.

He studied the chalk signs again. Had the pilgrim been here? Had the pilgrim been watching the 404th? He climbed back up to the crest, hoping to catch a glimpse of the red robe, but the pilgrim was out of sight. He moved southward again along the slope, looking for signs of the pilgrim's path. There was another goat path, but no sign of humankind, no sign of a demon.

He steered toward a rock outcropping that jutted from the side of the ridge, deciding that he would return to Feng and Yeshe when he reached it. But when he arrived at the huge rock formation he heard a bleating that carried him farther. Behind the rocks, shielded from the wind, was a pool of water. A small flock of sheep lay beside the pool, basking in the warmth. They watched him as he approached, but did not shy away. Shan squatted at the water, washed his face, then lay back on a flat rock that had gathered the sun's heat.

Without the wind the sunshine was luxuriant. He watched the animals for several minutes, then, on a whim, grabbed a handful of the gravel at the bottom of the rock and began to count the stones. It was a trick his father had taught him. Place the stones in piles of six and the number left would be used as the bottom digit in the tetragram for reading the Tao Te Ching. Four stones were left after the first round, indicating a broken line of two segments. He grabbed three more handfuls, until he built a tetragram of two solid lines over a triple segment and the double segment. In the Tao ritual it meant Passage Eight.

The greatest good is like water. The value of water is that it nourishes without striving.

He spoke the words out loud, with his eyes closed.

It stays in places that others disdain and therefore is close to the way of life.

It was the way he had learned with his father. They would use stones or rice– or on special occasions the ancient lacquered yarrow sticks that had belonged to his grandfather– then close their eyes and speak the verse.

In his mind's eye he conjured his father. They were alone, the two of them, in the secret temple in Beijing that had nourished them through so many difficult years. His heart leapt. For the first time in over two years he could hear his father's voice, echoing the verse. It was still there, not lost as he had feared, waiting in some remote corner of his mind for such a moment. He smelled the ginger that was always in his father's pocket. If he opened his eyes he would see the serene smile, made forever crooked by a Red Guard's boot. Shan lay motionless, exploring an alien feeling he suspected might be pleasure.

When he at last opened his eyes, the sheep had been spirited away. He had not heard them leave, and he could not see them on the slope. He rose with a peaceful expression, turned and froze. On a rock shelf above him sat a small figure bundled in an oversized sheepskin coat and wearing a red wool cap. He was smiling with great pleasure at Shan.

How had the man arrived so quietly? What had he done with the sheep?

"Spring sun is the best," the figure said in a voice that was strong and calm and high-pitched. It wasn't a man– it was a boy, an adolescent.

Shan shrugged uncertainly. "Your sheep are gone."

The youth laughed. "No. They are thinking I am gone. They will find me later. We only keep them so they will take us to high places. A meditation technique, in a way. It's always different. Today they brought me to you."

"A meditation technique?" Shan asked, not sure he had heard properly.

"You're one of them, aren't you?" the boy asked abruptly.

Shan did not know how to answer.

"Han. Chinese." There was no spite in the boy's words, only curiosity. "I've never seen one."

Shan stared at the boy in confusion. They were fifteen miles from the county seat. Twenty miles from a garrison of the PLA, and the boy had never seen a Han.

"But I have studied the works of Lao Tzu," the boy said, suddenly switching to fluent Mandarin.

So he had been there all the while. "You speak well for one who has never met a Han," Shan said, likewise in Mandarin.

The boy swung his legs out over the ledge. "We live in a land of teachers," he observed matter-of-factly. "Passage Seventy-one," he said, referring to the Tao Te Ching again. "You know Seventy-one?"

"To know that you do not know is best," Shan recited. "To not know of knowing is a disease." He considered the enigmatic boy. He spoke like a monk but was far too young. "Have you tried Twenty-four? The way of life means continuing. Continuing means going far. Going far means returning."

Pleasure lit the boy's face again. He repeated the passage.

"Does your family live on the mountain?"

"My sheep live on the mountain," the boy replied.

"Who does live on the mountain?" Shan pressed.

"The sheep live on the mountain," the boy repeated. He picked up a pebble. "Why did you come?"

"I think I am looking for Tamdin."

The boy nodded, as though expecting the answer. "When he is awakened the unpure must fear."

Shan noticed a rosary on his wrist, a very old rosary carved of sandalwood.

"Will you be able to turn your face toward Tamdin when you find him?" the boy asked.

Shan swallowed hard and considered the strange boy. It seemed the wisest question anyone could ask. "I don't know. What do you think?"

The serene smile returned to the boy's face. "The sound of the water is what I think," he said, and threw the pebble into the center of the pool.

Shan watched the circles ripple the surface, then turned. The boy was gone.

Feng was asleep against the rock cairn when he returned. Yeshe was sitting at the bridge, not five feet from where Shan had left him. The rancor had left his face.

"See any ghosts?" he asked Shan.

Shan looked back over the slope. "I don't know."

***

As Sergeant Feng cleared the last ridge and began to descend onto the plateau, he slowed the truck to consult the map. "Supposed to be a mine," he mumbled. "Nobody said anything about a fish farm."

Stretching below them were acres of manmade lakes, vast, neat rectangles arrayed across the high plain. Shan studied the scene in confusion. Three long, low buildings sat at the end of the road, arranged in a line in front of the lakes.

There was no activity at the mine, but a military truck was parked in front of the buildings. Tan had sent his engineers. A dozen men in green uniforms were clustered around the entrance to the center structure, listening to someone who sat on the step.

Shan and Yeshe were ignored as they ventured from the truck. But the moment Sergeant Feng emerged, the soldiers looked up. They quickly dispersed, studiously avoiding eye contact with their visitors. The figure sitting on the step was revealed, holding a clipboard. It was the American mine manager, Rebecca Fowler. Why, Shan suddenly wondered, would Tan send his engineers if the Ministry of Geology had suspended the mine's operating permit?

The American's only greeting was a frown. "The colonel's office called. Said you want to speak to us." She rose, holding the clipboard to her chest with folded arms as she spoke in slow, precise Mandarin. "But I don't know how to explain you to my team. He used the word unofficial."

"Theoretically this is an investigation for the Ministry of Justice."

"But you're not from the Ministry."

"In China," suggested Shan, "dealing with the government is something of an art form."

"He said it was about Jao. But he'd like to keep that secret. A theoretical investigation. Theoretical and secret," she said with challenge in her eyes.

"A monk has been arrested. It is no longer much of a secret."

"Then the matter is resolved."

"There is the matter of developing evidence."

"A monk was arrested without evidence? You mean he confessed?"

"Not exactly."

The American woman threw her arms up in exasperation. "Like getting my working papers. I applied from California. They said no working papers could be authorized because I wasn't here working. I said I would come here and apply. They said I couldn't travel here without working papers."

"You should have told them the capital for your project would not be transferred unless you were here to verify receipt."

Fowler flashed him a grimace that may have been part grin. "I did better. After sending faxes for three months I bought a ticket with a Japanese tour group to Lhasa. Hitched a ride to Jao's office in a truck and asked him to arrest me. Because I was about to start managing the county's only foreign investment without my working papers."

"That's how you met him?"

She nodded. "He thought about it for a few minutes and burst out laughing. Had the papers for me in two hours." She gestured toward the door and led them inside, into a large open room filled with desks arranged in two large squares. A few were occupied by Tibetans wearing white shirts. Most of them left the room as soon as they saw their visitors.

Fowler waited for them at the door to a conference room adjacent to the front door. But Shan moved to one of the desks. It was covered with strange maps of brilliant colors and no demarcation lines. He had never seen such a map before.

Fowler stepped to his side and threw a newspaper over the maps. An office worker called out that tea was ready in the conference room. Yeshe and Sergeant Feng followed him in.

Shan lingered at the desks. He spotted photographs of Buddhist artifacts, small statues of deities, prayer wheels, ceremonial horns, small thankga paintings on scrolled silk, all extended like trophies by anonymous arms. No faces were shown. "I am confused. Are you a geologist or an archaeologist?"

"The United Nations makes inventories of antiquities deserving preservation. They are part of the heritage of mankind. They do not belong to political parties."

"But you don't work for the United Nations."

"Don't you believe there are things that are common to all mankind?" she asked.

"I'm afraid so."

Rebecca Fowler stared at Shan uncertainly, then went for tea. Shan roamed around the square of desks. On the perimeter, behind walls of glass panels, there were two offices, labeled PROJECT MANAGER and CHIEF ENGINEER. Fowler's office was cluttered with files and more of the peculiar maps. The walls of the second office were hung with photos of Tibetans– candid, artful photos of children and ruined temples and windswept prayer flags. A shelf along one wall was filled with books about Tibet, in English.

A group photograph of a dozen exuberant men and women hung on the wall outside Fowler's office. Shan recognized Fowler, the blond American with wire-rimmed glasses, Assistant Prosecutor Li, and Chief Prosecutor Jao.

"The dedication of this building," Fowler explained as she handed him a mug of tea. "When we opened the facility officially."

Shan pointed to an attractive young Chinese woman with a brilliant smile. "Miss Lihua," Fowler said. "Jao's secretary."

"Why were Prosecutor Jao and the assistant prosecutor both involved in your operation?"

Fowler shrugged. "Jao was more the broad overseer. He delegated the supervisory committee issues to Li."

"You have telephones," Shan observed with a gesture toward the desks. "But I didn't see any wires."

"A satellite system," she explained. "We have to talk to our labs in Hong Kong. Twice a week we call our offices in California."

"And the UN office in Lhasa?"

"No. It's an internal system. Only authorized for designated receiving stations inside our company."

"Not even Lhadrung?"

Fowler shook her head. "I can contact California in sixty seconds. A message to Lhadrung means forty-five minutes' drive. Your country," she said without smiling. "It overflows with paradox."

"Like putting American saccharine in buttered tea," Shan said, watching a Tibetan woman in a white office smock pour pink packets into a bowl of the traditional milky brew.

There were bulletin boards with safety procedures in Chinese and English, and notices about staff meetings. At the back of the room a red door was closed, with a sign that restricted entry to authorized personnel.

"Has the American staff been here long, Miss Fowler?" Shan asked.

"It's only me and Tyler Kincaid. Eighteen months."

"Kincaid?"

"My chief engineer. Sort of second-in-command." She gave Shan a pregnant glance, which he took to mean that he had seen Kincaid with her at the cave. The lighthearted American who had played "Home on the Range" to spite Colonel Tan; the man in the building-dedication photo.

"No other Westerners? How about visitors from your company?"

"None. Too damned far. Only Jansen from the United Nations office in Lhasa. Week after next it all changes."

"You mean the American tourists."

"Right. Supposed to spend two hours here. After that, we're a regular stop on the tourist circuit. Guess we'll show them empty offices and empty tanks, give them a lecture on Chinese bureaucracy."

Shan refused the bait. "The UN Antiquities Commission. How are you involved?"

"Sometimes they ask to borrow a truck. Or some ropes."

"Ropes?"

"They explore caves. They climb mountains."

"Do they take artifacts?"

Fowler stiffened. "They record artifacts," she said with a stern look. "I guess you could say I am a member of the local committee."

"There's a committee?"

Fowler did not respond.

"What of the conflicts? Without government support you could not operate. Your mining license."

"Please don't remind me."

"And a permit to operate a satellite system, that is extraordinary. But you are opposing the government-"

Sergeant Feng appeared at Shan's side and made a sharp guttural sound, one of his warnings.

"– the government removal of artifacts," Shan continued, in English.

Rebecca Fowler's eyes flashed with surprise. "You speak it well," she said in her native tongue. "We are not in a position to stop anything the government does. We just believe governments should act openly in dealing with cultural resources, especially resources of a different culture. The Antiquities Commission helps collect evidence."

"So you have two jobs?"

Feng stepped between them with a resentful glare, but seemed uncertain what to do.

Fowler was six inches taller than Feng. She continued to speak, over his head, but switched back to Mandarin. "How about you, Inspector? How many jobs does an unofficial investigator have?"

Shan did not answer.

Fowler shrugged. "My job is mine manager. But the Commission has only one expatriate: Jansen. A Finn. He asks other expatriates working in the remote areas to serve as his eyes and ears."

"Your committee."

Fowler nodded, looking uncomfortably at Sergeant Feng.

"You still didn't say why you were at the cave."

"Didn't even know there was a cave. Until the PLA trucks got noticed."

"By whom?"

"Army trucks are conspicuous. One of my Tibetan engineers saw them when he was climbing."

"But army trucks can be explained in many ways."

"Not really. There're two patterns of truck traffic in the high ranges. Maneuvers. Or new construction for military camps or collectives. These weren't maneuvers, and there was no construction equipment entering the site. The trucks weren't carrying things in. Not much, anyway."

"So you decided they were carrying things out. Very clever."

"I couldn't be sure. But as soon as I arrived I saw two things. Your colonel. And a cave crawling with soldiers."

"The colonel could have other reasons to be there."

"You mean the murder?"

"I have had several American friends," Shan observed. "They are always quick to jump to conclusions."

"There's a difference between jumping to conclusions and being direct. Why don't you just say no? Tan would just say no. Jao would just say no, if it suited." She ran her fingers through her hair. Shan realized she did it when she was nervous. "That day at Tan's office, you openly defied him. You're not like other Chinese I've known."

It was going too fast. Shan drained his cup and asked for more. As Fowler moved toward the conference room by the door he studied the bulletin board. There was a hand-written document in one corner, in Tibetan. With a start, Shan recognized it. It was the American Declaration of Independence. He led Sergeant Feng away from it, to the conference room, where Fowler sat on the table, waiting for him with the tea.

"So you are replacing Prosecutor Jao?" Fowler asked.

"No. Just a short assignment for the colonel."

"He would have been disappointed. Jao used to read Arthur Conan Doyle. Loved his murder investigations."

"You make it sound like a habit."

"Half a dozen a year, I suppose. It's a big county."

"He always solved them?"

"Sure. It was his job, right?" she asked in a taunting tone. "And now you have already arrested the murderer."

"I didn't arrest anyone."

Fowler studied Shan. "You sound like you don't think he did it."

"I don't."

Fowler could not conceal her surprise. "I'm beginning to understand you, Mr. Shan."

"Just Shan."

"I understand why Tan wanted you away from the cave when I was there. You're– what? Unpredictable, like he described the Tibetans. I don't think your government deals well with unpredictability."

Shan shrugged. "Colonel Tan prefers to deal with one crisis at a time."

The American woman studied him. "So what was his crisis, you or me?"