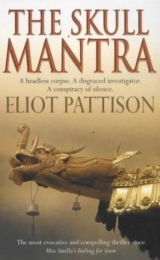

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Chapter Three

The drab three-story building that housed the People's Health Collective proved far more sterile outside than inside. The odor of mildew wafted through the lobby. On the lobby wall, a collage of bulldozers and tractors mounted by beaming proletarians was cracked and peeling. The same bone-dry dust that filled the 404th barracks covered the furniture. Brown and green stains ran across the faded linoleum floor and up one wall. Nothing moved but a large beetle that scuttled toward the shadows as they entered.

Madame Ko had called. A short, nervous man in a threadbare smock appeared, and silently led Shan, Yeshe, and Feng down a dimly lit flight of stairs to a basement chamber with five metal examination tables. As he opened the swinging doors, the stench of ammonia and formaldahyde broke over them like a wave. The aroma of death.

Yeshe's hands shot to his mouth. Sergeant Feng cursed and fumbled for a cigarette. More of the dark stains Shan had seen upstairs mottled the walls. He followed one with his eyes, a spatter of brown spots that arced from floor to ceiling. On one wall was a poster, tattered from repeated folding, that announced a performance, years earlier, of the Beijing Opera. With a mixture of disgust and fear, their escort gestured toward the only occupied table, then backed out of the room and closed the door.

Yeshe turned to follow the orderly.

"Going somewhere?" Shan inquired.

"I'm going to be sick," Yeshe pleaded.

"We have an assignment. You won't get it done waiting in the hall."

Yeshe looked at his feet.

"Where do you want to be?" Shan asked.

"Be?"

"Afterward. You're young. You're ambitious. You have a destination. Everyone your age has a destination."

"Sichuan province," Yeshe said, distrust in his eyes. "Back to Chengdu. Warden Zhong told me he has my papers ready. Says he's arranged for me to have a job there. People can rent their own apartments now. You can even buy televisions."

Shan considered the announcement. "When did the warden say this?"

"Just last night. I still have friends back in Chengdu. Members of the Party."

"Fine." Shan shrugged. "You have a destination and I have a destination. The sooner we get done, the sooner we can move on."

Resentment still etched on his face, Yeshe found a wall switch and illuminated a row of naked lightbulbs hanging over the tables. The center table seemed to glow, its white sheet the only clean, bright object in the room. Sergeant Feng muttered a low curse toward the far side of the room. A body was slumped in a rusty wheelchair, covered with a soiled sheet, its head slung over the shoulder at an unnatural angle.

"They just leave you like that," Feng growled in contempt. "Give me an army hospital. At least they lay you out in your uniform."

Shan looked back at the arc of bloodstains. This was supposed to be the morgue. Corpses had no blood pressure. They did not spray blood.

Suddenly the body in the chair groaned. Revived by the light, it swung its arms stiffly to pull down the sheet, then produced a pair of thick, horn-rimmed glasses.

Feng gasped and retreated toward the door.

It was a woman, Shan realized, and it wasn't a sheet that covered her but a vastly oversized smock. From its folds she produced a clipboard.

"We sent the report," she declared in a shrill, impatient tone, and stood. "No one understood why you needed to come." Bags of fatigue shadowed her eyes. In one hand she held a pencil like a spear. "Some people like to look at the dead. Is that it? You like to gawk at the corpses?"

A man's life, Choje taught his monks, did not move in a linear progression, with each day an equal chit on the calendar of existence. Rather it moved from defining moment to defining moment, marked by the decisions that roiled the soul. Here was such a moment, Shan thought. He could play Tan's hound, starting here and now, trying to somehow save the 404th or he could turn around, as Choje would want, ignoring Tan, being true to all that passed as virtue in his world. He clenched his jaw and turned to the diminutive woman.

"We will need to speak to the doctor who performed the autopsy," Shan said. "Dr. Sung."

Inexplicably, the woman laughed. From another fold of her smock she pulled a koujiao, one of the surgical masks used by much of the population of China to ward off dust and viruses in the winter months. "Other people. Other people just like to cause trouble." She tied the mask over her mouth and gestured toward a box of kiajiou on the nearest table. As she walked, a stethoscope appeared in the folds of the smock.

There was still a way, a narrow opening he might wedge through. He would have to get the accident report signed. An accident caused by the 404th would answer Tan's needs without the agony of a murder investigation. Sign the report, then find a way to conduct death rites for the lost soul. To answer the political dilemma, the 404th could be disciplined for negligent behavior. A month on cold rations, perhaps a mass reduction of every prisoner. It would be summer soon; even the old ones could survive a reduction. It was not a perfect solution, but it was one within his reach.

By the time the three men fastened their masks, she had stripped the sheet from the body and pulled a clipboard from the table.

"Death occurred fifteen to twenty hours before discovery, meaning the evening before," she recited. "Cause of death: traumatic simultaneous severance of the carotid artery, jugular vein, and spinal cord. Between the atlas and the occipital." She studied the three men as she spoke, then seemed to dismiss Yeshe. He was obviously Tibetan. She paused over Shan's threadbare clothes and settled on addressing Sergeant Feng.

"I thought he was decapitated," Yeshe said hesitantly, glancing at Shan.

"That's what I said," the woman snapped.

"You can't be more specific about the time?" Shan asked.

"Rigor mortis was still present," she said, again to Feng. "I can guarantee you the night before. Beyond that…" She shrugged. "The air is so dry. And cold. The body was covered. Too many variables. To be more precise would require a battery of tests."

She saw the expression on Shan's face and threw him a sour look. "This isn't exactly Beijing University, Comrade."

Shan studied the poster again. "At Bei Da you would have had a chromatograph," he said, using the colloquial expression for Beijing University, the reference most commonly used in Beijing itself.

She turned slowly. "You are from the capital?" A new tone had entered her voice, one of tentative respect. In their country, power came in many shapes. One could not be too careful. Maybe this would be easier than he'd thought. Let the investigator live just a few moments, long enough to make her understand the importance of the accident report.

"I had the honor of teaching a course with a professor of forensic medicine at Bei Da," he said. "Just a two-week seminar, really. Investigation Technique in the Socialist Order."

"Your skills have served you well." She seemed unable to resist sarcasm.

"Someone said my technique involved too much investigation, not enough of the socialist order." He said it with an edge of remorse, the way he had been trained to do in tamzing sessions.

"Here you are," she observed.

"Here you are," he shot back.

She smiled, as though he were a great wit. When she did so the bags under her eyes disappeared for a moment. He realized that she was slender beneath the huge gown. Without the bags, and without her hair tied so severely behind her, Dr. Sung could have passed for a stylish member of any Beijing hospital staff.

Silently she made a complete circuit of the table, studying Sergeant Feng, then Shan again. She approached Shan slowly, then suddenly grabbed his arm, as if he might bolt away. He did not resist as she rolled up his sleeve and studied the tattooed number on his forearm.

"A trusty?" she asked. "We have a trusty who cleans the toilets. And one to wipe up the blood. Never had one sent to interrogate me." She paced about him with intense curiosity, as though contemplating dissection of the strange organism before her.

Sergeant Feng broke the spell with a sharp, guttural call. It was not a word, but a warning. Yeshe was attempting to ease the door open. He stopped, confused but obsequious, and retreated to the corner, where he squatted against the wall.

Shan read the report hanging at the end of the table. "Dr. Sung." He pronounced her name slowly. "Did you perform any tissue analysis?"

The woman looked to Feng as though for help, but the sergeant was inching away from the corpse. She shrugged. "Late middle-aged. Twenty-five pounds overweight. Lungs beginning to clog with tar. A deteroriated liver, but he probably didn't know it yet. Trace of alcohol in his blood. Ate less than two hours before death. Rice. Cabbage. Meat. Good meat, not mutton. Maybe lamb. Even beef."

Cigarettes, alcohol, beef. The diet of the privileged. The diet, he comforted himself, of a tourist.

Feng found a bulletin board, where he pretended to read a schedule of political meetings.

Shan moved slowly around the table, forcing himself to study the truncated shell of the man who had stopped the work of the 404th and forced the colonel to exhume Shan from the gulag, the man whose unhappy spirit now haunted the Dragon Claws. With his pencil he pushed back the lifeless fingers of the left hand. It was empty. He moved on, paused and studied the hand again. There was a narrow line at the base of the forefinger. He pushed it with the eraser. It was an incision.

Dr. Sung donned rubber gloves and studied the hand with a small pocket lamp. There was a second cut, she announced, in the palm just below the thumb.

"Your custodial report said nothing about removing an object from the hand." It had been something small, no more than two inches in diameter, with sharp edges.

"Because we didn't." She bent over the incision. "Whatever was there was wrenched free after death. No bleeding. No clotting. Happened afterward." She felt the fingers one by one and looked up with a blush of embarrassment. "Two of the phalanges are broken. Something squeezed the hand with great force. The death grip was broken open."

"To get at what it held."

"Presumably."

Shan considered the woman. In Chinese bureaucracies, there was a gray line between humanitarian service to the struggling colonies and outright exile. "But can you be so sure of the cause? Perhaps he died in a fall and later, for unrelated reasons, his head was removed."

"Unrelated reasons? The heart was still pumping when the head was severed. Otherwise there would have been much more blood in the body."

Shan sighed. "With what then? An axe?"

"Something heavy. And razor-sharp."

"A rock, possibly?"

Dr. Sung responded with a peevish frown and yawned. "Sure. A rock as sharp as a scalpel. It wasn't a single blow. But no more than three, I'd say."

"Was he conscious?"

"At the time of death he was unconscious."

"Surely you cannot know, without the head."

"His clothes," Dr. Sung said. "There was almost no blood on his clothes. No skin or hair under the nails. No scratches. There was no struggle. His body was laid out so the blood would drain away from it. Face up. We extracted soil and mineral particles from the back of his sweater. Only the back."

"But it's just a theory, that he was unconscious."

"And your theory, Comrade? That he died by falling on a rock and someone who collected heads happened along?"

"This is Tibet. There is an entire social class dedicated to cutting up bodies for disposal. Perhaps a ragyapa happened along and began the rite for sky burial, then was interrupted."

"By what?"

"I don't know. The birds."

"They don't fly at night," she grumbled. "And I've never seen a vulture big enough to carry a skull away." She pulled a paper from the clipboard. "You must be the fool who sent me this," she said. It was the accident report form, ready for her signature.

"The colonel would feel better if you just signed it."

"I don't work for the colonel."

"I told him that."

"And?"

"It's a subtle point for a man like the colonel."

Sung threw him one last glare, nearly a snarl, then silently ripped the form in half. "How's this for subtle?" She tossed the pieces on the naked corpse and marched out of the room.

***

Jilin the murderer was obviously invigorated by his new status as the leading worker of the 404th. He loomed like a giant at the front of the column, slamming his sledgehammer into the boulders, pausing occasionally to turn with a gloating expression toward the knots of Tibetan prisoners seated on the slope below. Shan studied the others, a dozen Chinese and Moslem Uyghurs not usually seen on the road crews. Zhong had sent the kitchen staff to the South Claw.

Shan found Choje, sitting lotus fashion, his eyes closed, in the center of a ring of monks near the top. Their idea was to protect Choje when the guards eventually moved in. It only meant that the guards would be all the more furious when they eventually reached him.

But the guards sat around the trucks, smoking and drinking tea brewed over an open wood fire. They were not watching the prisoners. They were watching the road from the valley.

Jilin's jubilance faded when he saw Shan. "They say you're a trusty now," he said bitterly, punctuating the sentence with a slam of the hammer.

"Just a few days. I'll be back."

"You're missing everything. Triple rations if you work. Damned locusts gonna get their wings broken. Stable gonna be full. We'll be heroes." Locusts. It was a label of contempt for the Tibetan natives. For the droning sound of their mantras.

Shan studied the four small cairns that had been raised to mark where the body had been found. He slowly walked around the site, sketching it in his notebook.

Sung was right. The killer had done his work here. This was the butchering ground. He had killed the man, and thrown the contents of his pockets over the cliff. But why had he missed the shirt pocket, under the sweater, which held the American money? Because, Shan mused, his hands had been so bloody and the white shirt so clean.

"Why come this far from town and not throw the body over the cliff? It would never have been found." The query came from behind. Yeshe had followed Shan up the slope. It was the first time Yeshe had shown any interest in their assignment.

"It was supposed to be found." Shan knelt and pushed away the remaining rocks from the rust-colored stain.

"Then why cover it with rocks?"

Shan turned and studied Yeshe, then the monks who had begun to watch him nervously. Jungpos only came out at night. But by day the hungry ghosts hid in small crevasses or under rocks.

"Maybe because then the guards would have seen it from a distance."

"But the guards did find it," Yeshe argued.

"No. Prisoners found it first. Tibetans."

Shan left Yeshe staring uneasily at the cairns and walked over to Jilin. "I need you to hang me over the edge."

Jilin lowered his hammer. "You're one crazy shit."

Shan repeated the request. "Just a few seconds. Over there," he pointed. "Hold my ankles."

Jilin slowly followed Shan to the edge, then smirked. "Five hundred feet. Lots of time to think before you hit. Then you're just like a melon fired from a cannon."

"A few seconds, then you pull me back."

"Why?"

"Because of the gold."

"Like hell," Jilin spat. But then, with a suspicious gleam he leaned over the edge. "Shit," he said as he looked up in surprise. "Shit," he repeated, then quickly sobered. "I don't need you."

"Sure you do. You can't reach it from the top. Who do you trust to lower you?"

A spark of understanding kindled on Jilin's face. "Why trust me?"

"Because I'm going to give you the gold. I'm going to look at it, then I'll give it to you." Jilin could only be relied upon for his greed.

A moment later Shan was upside down, suspended by his ankles over the abyss. His pencil fell out of his pocket and plunged end over end through the void. He closed his eyes as Jilin laughed and bobbed him up and down like a child's marionette. But when he opened them the lighter was directly in front of him.

In an instant he was back on top. The lighter was Western-made but engraved with the Chinese ideogram for long life. Shan had seen such lighters before; they were often tokens distributed at party meetings. He breathed on it, letting his breath fog the surface. No fingerprints.

"Give it to me," Jilin growled. He was watching the guards.

Shan closed his hand around it. "Sure. For a trade."

Jilin's eyes went wild. He raised his fist. "I'll break you in half."

"You took something from the body. Pulled it out of the hand. I want it."

Jilin seemed to be considering whether he would have time to grab the lighter while he pushed Shan off the edge.

Shan stepped out of his reach. "I don't think it was valuable," Shan said. "But this-" He lit the flame. "Look. Wind-resistant." He extended it, increasing the risk the guards would see it.

Instantly Jilin reached into his pocket and produced a small tarnished metal disk. He dropped it into Shan's palm and grabbed the lighter. Shan held onto it. "One more thing. A question."

Jilin snarled and looked back down the slope. As much as he might wish to crush Shan, the first sign of struggle would bring the guards.

"Your professional perspective."

"Professional?"

"As a murderer."

Jilin swelled with pride. His life, too, had its defining moments. He eased his grip.

"Why here?" Shan asked. "Why go so far from town but leave the body so conspicuous?"

An unsettling longing appeared in Jilin's eyes. "The audience."

"Audience?"

"Someone told me once about a tree falling down in the mountains. It don't make a sound if no one's there to hear. A killing with no one to appreciate it, what's the point? A good murder, that requires an audience."

"Most murderers I've known act in private."

"Not witnesses, but those who discover it. Without an audience there can be no forgiveness." He recited the words carefully, as if they had been taught to him in tamzing sessions.

It was true, Shan realized. The body had been discovered by the prisoners because that was what the murderer intended. He paused, looking into Jilin's wild eyes, then released the lighter and looked at the disc. It was convex, two inches in width. Small slots at the top and bottom indicated that it had been designed to slide onto a strap for ornamentation. Tibetan script, in an old style that was unintelligible to Shan, ran along the edge. In the center was the stylized image of a horse head. It had fangs.

***

As Shan approached Choje, the protecting circle parted. He was uncertain whether to wait until the lama finished his meditation. But the moment Shan sat beside him, Choje's eyes opened.

"They have procedures for strikes, Rinpoche," Shan said quietly. "From Beijing. It's written in a book. Strikers will be given the opportunity to repent and accept punishment. If not, they will try to starve everyone. They make examples of the leaders. After one week a strike by a lao gai prisoner may be declared a capital offense. If they feel generous, they could simply add ten years to every sentence."

"Beijing will do what it must do," came the expected reply. "And we will do what we must do."

Shan quietly studied the men. Their eyes held not fear, but pride. He swept his hand toward the guards below. "You know what the guards are waiting for." It was a statement, not a question. "They are probably already on the way. This close to the border, it won't take long."

Choje shrugged. "People like that, they are always waiting for something." Some of the monks closest to them laughed softly.

Shan sighed. "The man who died had this in his hand." He dropped the medallion in Choje's hand. "I think he pulled it from his murderer."

As Choje's eyes locked on the disc, they flashed with recognition, then hardened. He traced the writing with his finger, nodded, and passed it around the circle. There were several sharp cries of excitement. As the men passed it on, their eyes followed the disc with looks of wonder.

There had been no real struggle between the murderer and his victim, Shan knew. Dr. Sung had been right on that point. But there had been a moment, perhaps just an instant of realization, when the victim had seen, then touched his killer, had reached out and grabbed the disc as he was being knocked unconscious.

"Words have been spoken about him," Choje said. "From the high ranges. I wasn't sure. Some said he had given up on us."

"I don't understand."

"They were among us often in the old days." The lama's eyes stayed on the disc. "When the dark years came they went deep inside the mountains. But people said they would come back one day."

Choje looked back to Shan. "Tamdin. The medallion is from Tamdin. The Horse-Headed, they call him. One of the spirit protectors." Choje paused and recited several beads then looked up with an expression of wonder. "This man without a head. He was taken by one of our guardian demons."

As the words left Choje's mouth, Yeshe appeared at the edge of the circle. He studied the monks awkwardly, as though embarrassed or even fearful. He seemed unwilling, or unable, to cross into the circle. "They found something," he called out, strangely breathless. "The colonel is waiting at the crossroads."

***

One of the first roads built by the 404th had been the one that ringed the valley, connecting the old trails that dropped out of the mountains between the high ridges. The road the two vehicles now followed up the Dragon Claws had been one of those trails, and was still so rough a path that it became a streambed during the spring thaws. Twenty minutes after leaving the valley, Tan's car led them onto a dirt track that had been recently scoured by a bulldozer. They emerged onto a small, sheltered plateau. Shan studied the high, windblown bowl through the window. At its bottom was a small spring, with a solitary giant cedar. The plateau was closed to the north. It opened to the south, overlooking fifty miles of rugged ranges. To a Tibetan it would have been a place of power, the kind of place a demon might inhabit.

A long shed with an oversized chimney came into view as Feng eased the truck to a stop. It had been built recently, of plywood sheets torn from some other structure. The sections of wood displayed remnants of painted ideograms from their prior incarnation, giving the shed the appearance of a puzzle forced together from mismatched pieces. Several four-wheel drive vehicles were parked behind it. Beside them half a dozen PLA officers snapped to attention as Tan emerged from his car.

The colonel conferred briefly with the officers and gestured for Shan to join him as they walked behind the shed. Yeshe and Feng climbed out and began to follow. An officer looked up in alarm and ordered them back into the truck.

Twenty feet behind the shed was the entrance to a cave, riddled with fresh chisel marks. It had been recently widened. Several officers filed toward the cave. Tan barked an order and they halted, yielding to two grim-faced soldiers with electric lanterns who stepped forward at Tan's command. The others stood and watched, whispering nervously as Shan followed Tan and the two soldiers into the cave.

The first hundred feet was a cramped, tortuous tunnel, strewn with the litter of mountain predators, which had been kicked to the sides to make way for the barrows whose wheel tracks ran down the center. Then the shaft opened into a much larger chamber. Tan stopped so abruptly Shan nearly collided with him.

Centuries earlier, the walls had been plastered and covered with murals of huge creatures. Something clenched Shan's heart as he stared at the images. It wasn't the sense of violation because Tan and his hounds were there. Shan's entire life had been a series of such violations. It wasn't the fearsome image of the demons which, in the trembling lights held by the soldiers, seemed to dance before their eyes. Such fears were nothing compared to those Shan had been taught at the 404th.

No. It was the way the ancient paintings awed Shan, and shamed him, made him ache to be with Choje. They were so important, and he was so small. They were so beautiful, and he was so ugly. They were so perfectly Tibetan, and he was so perfectly nobody.

They moved closer, until fifty feet of the wall was awash in the soldiers' lights. As the deep, rich colors became apparent, Shan began to recognize the images. In the center, nearly life-size, were four seated Buddhas. There was the yellow-bodied Jewel Born Buddha, his left palm open in the gesture of giving. Then the red-bodied Buddha of Boundless Light, seated on a throne decorated with peacocks of extraordinary detail. Beside them, holding a sword and with his right hand raised, palm outward in the mudra of dispelling fear, was the Green Buddha. Finally there was a blue figure, the Unshakeable Buddha Choje called him, sitting on a throne painted with elephants, his right hand pointed down in the earth-touching mudra. It was a mudra Choje often taught to new prisoners, calling for the earth to witness their faith.

Flanking the Buddhas were figures less familiar to Shan. They had the bodies of warriors, wielded bows and axes and swords, and stood over the bones of humans. To the left, closest to Shan, was a cobalt blue figure with the head of a fierce bull. Around his neck was a garland of snakes. Beside him was a brilliant white warrior with the head of a tiger. Around them were the much smaller figures of an army of skeletons.

Suddenly Shan understood. They were the protectors of the faith. As he moved forward he saw that the feet of the tiger demon were discolored. No, not discolored. Someone had crudely attempted to chisel out a piece of the mural and failed. A small pile of colored plaster lay on the ground below the figure.

His light began to fade. The soldiers were moving down the wall to the far side of the huge chamber. Two more demons came into focus, a green-bodied one with a huge belly and a monkey's head, holding a bow and waving a bone, then finally a red beast with four fangs set in a furious expression and, on an appendage above its golden hair, the small green head of a savage horse. A tiger skin was draped over one shoulder. The beast stood in blazing flames surrounded by bones. Shan's hand clamped around the disc in his pocket, the ornament torn from the murderer. He resisted the temptation to pull the disc from his pocket. He was certain the images of the fanged horse matched.

The lights shifted away from the wall and focused on Colonel Tan's boots, giving him the eerie, larger-than-life appearance of yet another demon. "Things have changed," he announced suddenly.

Shan studied the grim faces of their escort. His heart lurched again. He knew what men like Tan did in such places. Deep in the mountain nothing would be heard outside. Not a scream. Not a gunshot. Nothing could be heard, and nothing would be found afterward. Jilin was wrong. Not all murders were done for forgiveness.

Tan handed Shan a piece of folded paper. It was his copy of Shan's accident report. "We won't be using this," he said.

His hand trembling, Shan accepted it.

Tan followed the soldiers toward a side tunnel. Before he entered it he turned and impatiently gestured for Shan to join them. Shan looked back. There was nowhere to run. Another twenty soldiers waited outside. He looked again at the painted images, empty with despair. Wishing he knew how to pray to demons, he slowly followed.

There was a vague odor in the tunnel. Not incense, but the dust that remains when the scent of incense has long settled. Ten feet into the passage, past a small pair of demon protectors painted on either wall like sentinels, shelves appeared. They had been constructed of stout timber decades, maybe centuries, earlier, over a foot wide, four shelves on each wall connected to vertical risers with pegs. For the first thirty feet along the passage they were empty. After that they were packed full, from floor to ceiling, their glittering contents extending beyond the the reach of the lamps.

A deep chill wracked Shan's gut. "No!" he cried, in pain.

Tan, too, halted suddenly, as though physically struck. "I had read the report of the discovery weeks ago," he said in a near whisper. "But I never imagined it like this."

They were skulls. Hundreds of skulls. Skulls as far as Shan could see. Each sat in a tiny altar created by a semicircle of religious ornaments and butter lamps. Each skull was plated with gold.

Tan touched one of the skulls with a tentative fingertip, then lifted it. "A team of geologists found the cave. At first they thought they were sculptures, until they turned one over." He flipped the skull and rapped the inside surface with a knuckle. "Just bone."

"Don't you understand what this place is?" Shan asked, aghast.

"Of course. A gold mine."

"Sacred ground," Shan protested. He put his hands around the skull in the colonel's hands. "The holiest of artifacts." Tan relented, and Shan returned the skull to its shelf. "Some monasteries preserved the skulls of their most revered lamas. The living Buddhas. This is their shrine. More than a shrine. It has great power. It must have been used for centuries."

"An inventory was taken," Colonel Tan reported. "For the cultural archives."

Suddenly, with horrible clarity, Shan understood. "The chimney." The word came out in a dry croak.

"In the fifties," Tan declared, "an entire steel mill in Tientsin was funded with gold salvaged from Tibetan temples. It was a great service to the people. A plaque was erected thanking the Tibetan minorities."

"It's a tomb you're-"

"Resources," Tan interrupted, "are in tight supply. Even the bone fragments have been classified a byproduct. A fertilizer plant in Chengdu has agreed to buy them."

They stood in silence. Shan fought the urge to kneel and recite a prayer.

"We're going to initiate it," Tan declared. "Officially. The murder investigation."

Shan suddenly remembered. He looked at the report in his hand, his heart racing. Tan had a real investigator. He wanted to eliminate traces of his false start.