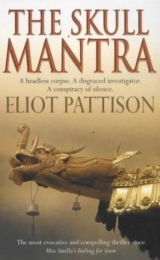

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 26 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Fowler's sigh was almost a sob. "If my mine was hiding someone's evidence," she said, "we could be deported, couldn't we?"

Shan did not reply, and watched as she slowly followed Kincaid. Five minutes later Shan found her in the computer room, her head in her hands, staring into a cup of tea. Kincaid was there, playing slow, sad notes on his harmonica, one hand urgently scrolling text on the screen of the satellite console.

"It's over," Shan said as he sat across from her.

"Damned straight. I'll lose my job. I'll lose my reputation. I'll be lucky if they give me airfare home." Everything about Rebecca Fowler, her voice, her face, her very being, seemed to have been hollowed out.

"It wasn't your fault. The army will rebuild your dam. The Ministry of Geology will receive an official explanation. This is Party business. They will clean it up quietly."

"I don't even know what to report home."

"An accident. An act of nature."

Fowler looked up. "That poor woman. We knew her. Tyler took her hiking sometimes."

"I saw her in the photo on the wall." Shan nodded. "But I believe she knew what Prosecutor Jao knew. If Jao had to die, so did she."

"Someone said she was on leave."

"Someone lied." He remembered how excited Tan had been when he had established contact with Lihua by fax. The faxes had indeed come from Hong Kong. Shan had seen the telephone transmission codes. The source had even been identified as the local Ministry of Justice office. Someone had lied in Hong Kong. Li, who had reported taking her to the airport the night she died, had lied in Lhadrung.

"The satellite photos and the water permits," Fowler said. "It was somehow about them."

"I'm afraid so."

Fowler buried her head in her hands again. "You mean I started it all?"

"No. What you started was the end of it all."

"The end of Jao. The end of Lihua." Her voice was desolate.

"No. Jao was already marked for murder. They probably would have eventually found a way for Miss Lihua to disappear."

Fowler looked up with a haunted expression.

"There were five murders really, five that we know of. Plus the three innocent men wrongly executed." Shan poured himself some tea from a thermos on the table before continuing. After seeing the body in the car he felt he might never get the chill out of his gut. "It seemed hopelessly confused. What I didn't understand at first was that there were two cases, not one. The murder of Prosecutor Jao. And Jao's investigation. I couldn't understand the murder without understanding what Jao was tracking. And the motives. Not one, not two, but several, all coming together that night on the Dragon's Claw."

"Five murders? Jao. Lihua-"

"And the victims of the earlier trials. The former Director of Religious Affairs. The former Director of Mines. The former Manager of the Long Wall collective. Then the monks. I never believed the Lhadrung Five were guilty. But the likely suspects never fit the crime. No pattern. Because it wasn't a single man. It was all of them."

"All of them? Not all the purbas."

Shan shook his head and sighed. "The hardest thing was connecting the victims. They were all the leaders of a large government operation so they were symbolic of the injury inflicted on Tibetans. The activists were instant suspects. But no one focused on a more immediate motive. The victims were also officials. And they were all old."

"Old?"

"They were the senior officials in their offices. Very powerful offices. Among them, they ran most of the county. And below each of them, next in line, was someone much younger, a member of the Bei Da Union." He stood behind the console. Kincaid was calling up the log of map orders.

Rebecca Fowler's mouth opened but she seemed unable to speak. "You mean the Union was like some sort of club for murderers?" she finally asked.

Shan paced along the long table. "Li was successor to Jao. Wen took over the Religious Affairs Bureau when Lin died. Hu took over at the Ministry of Geology. The head of the Long Wall collective didn't have to be replaced, because it was dissolved due to its criminal activities. Maybe they didn't even know about it when they started the killing. But when they discovered it generated huge revenues as a drug supplier, how could they resist?" What was it Li had said the first time they had met? Tibet was a land of opportunity. He picked up one of the glossy American catalogs and slid it toward Fowler. "Most of the things in here cost more than they make in a month on their official salaries."

Kincaid still sat staring at the computer monitor. He had stopped blowing into his harmonica. His knuckles, gripping the edge of the table, were white. "You showed him," he whispered. "You showed Shan the maps. There were none in the files so you actually transmitted them down for him. You never order maps on your own."

Fowler turned toward him, not understanding. "I had to, Tyler, it was about Jao's murder. Those water rights we never understood."

But Kincaid was looking at Shan, who had moved close enough to read the screen. It was not the computer log for Jao's poppy fields Kincaid was studying. It was the log for the maps of the South Claw. The maps that had revealed Yerpa to the American engineer.

"When we studied the photos taken of the skulls in the cave, we found the one that had been moved," Shan said. "Not destroyed, just reverently moved. I thought it meant a monk had been there. But a monk would have been able to read the Tibetan date with each skull. He would be unlikely to tamper with the order, the sequence of the shrine. Much later I realized someone could have been reverent toward the skull but not able to read Tibetan." Kincaid seemed not to have heard.

"You mean it was a Chinese," Fowler said weakly.

Shan lowered himself wearily into a chair across from Fowler and decided to try a different direction. "The Lotus Book can be easily misunderstood."

"The Lotus Book?" Fowler asked.

Shan clasped his hands together on the table and stared into them as he spoke. An immense sadness, an almost paralyzing melancholy, had settled over him. "It isn't about revenge," he went on. Kincaid was slowly turning to face him. "It isn't about vindication. The purbas don't mind committing treason in compiling the records, but they will not kill. The Book's just– it's very Tibetan. A way of shaming the world. A way of enshrining the lost ones. But not for killing. That's not the Tibetan way." Shan looked up. Why, he wondered, did justice always taste so bitter?

"I don't understand anything you're-" Fowler stopped in midsentence as she saw that Shan was gazing not at her, but over her shoulder at Kincaid.

"I couldn't understand until I saw Jansen with the purbas. Then I knew. He was the missing link. You gave the information to Jansen. Jansen gave it to the purbas. The purbas put it in the Lotus Book. You just passed on what your good friends gave you. Li, and Hu, and Wen, you thought they were trying to create a new, friendlier government, to heal the old wounds by helping the Tibetans. You had no way of knowing the information was lies. You would never have suspected, because it had so much virtue behind it. Everyone was ready to believe that Tan and Jao did those things. You even got your friends to donate military food and clothing as a token of their commitment. A truck of clothes went to the ragyapa village, which you knew about and felt sorry for because of Luntok."

Rebecca Fowler pushed her chair back and stood. "What are you talking about?" she demanded. "A book? The murders had to do with the Tamdin demon, you said. A Tibetan in the demon's costume."

Shan nodded slowly. "The Bureau of Religious Affairs did audits of the gompas, you know. They found the Tamdin costume a year and a half ago. It had belonged to Sungpo's guru and he had hidden it all these years. But he was going senile, and probably got careless about protecting it. Director Wen hid the audit report describing the discovery and, since so many clerks knew about the audit, a shipment was sent to the museum to cover the tracks. But Director Wen never sent the costume to the museum, because the Bei Da Union had met someone who could use it for them. Someone who would never need an alibi for murder because he would never be suspected. Someone who would revel in the symbolism. Someone with special powers. Strong. Fearless. Absolute in his convictions about the Tibetan people. About the need to take revenge for the pillage of Tibet." Or maybe, Shan considered, the need to take revenge on the world at large.

"To kill a man with pebbles, one by one. To sever a man's head with three blows. Not everyone is capable of such things. And to use the costume, it would take someone very special. The Tibetans trained for months, but that was mostly for the ceremony. Someone not interested in the ritual could have mastered the costume much more quickly, especially someone trained as an engineer."

Kincaid moved to the wall with his photographs of Tibetans and stared at the faces of the children, women, and old men as if they held an answer. "Wrong," he said in a hollow voice. "You have it so wrong."

Shan slowly rose. Kincaid began to retreat, as though fearful of attack. But Shan moved to the console. "No, I had it very wrong. I couldn't believe that such contempt, and yet such reverence, could exist in the same person." The computer screen still showed the data on the Yerpa maps. It was extraordinary how well the American had come to understand the Tibetans. In its own way, the killing of Prosecutor Jao had been an act of genius. The American, having discovered Yerpa on the photo maps, had known the 404th would stop work on the road, and no doubt had assumed the major would see that the knobs went through the motions but inflicted no real harm on the 404th. Shan hit the delete button.

There was the sound of more machines outside. Rebecca Fowler moved to the doorway of the room and stared out the window on the far wall. "A flatbed truck," she said distractedly. "They're taking away Jao's limousine."

She turned back, her face a mask of confusion. "Tyler, if you know something you should tell Shan. We have the mine to think of. The company."

"Know something?" Kincaid said with contempt. "Sure, I know something. The Lhadrung Five. They weren't executed. That's how wrong you are. Only ones who died were a bunch of MFCs who should have been executed years ago for their crimes against Tibet." He seemed angry. "Except Lihua," he added hesitantly. "Someone got carried away."

Fowler's head snapped up. "How could you know– what do you mean?" she asked.

"The club. The Bei Da Union," Shan said. "Li, Wen, Hu, the major. Mr. Kincaid was an unofficial member."

"Someone has to act, Rebecca," Kincaid interjected with an impassioned tone. "You know that, it's why you help with the UN and Jansen. Tibet has so much to teach the world. We have to clear the slate. We've made great progress."

"Progress?" Fowler asked in a near whisper.

"Someone has to stand up," Kincaid shot back. "It has to be done. No one stood up to Hitler. No one stood up to Stalin until it was too late. But it's not too late here. This is where we can make a difference. History can be turned around. The Bei Da Union knows that. Criminals have to be turned out of power."

"Can you recognize a criminal, Mr. Kincaid?" Shan asked. Without waiting for an answer, he turned to Fowler. "Do you have a shipment of samples being prepared for transport next week?"

"Yes," Fowler said slowly, more perplexed than ever.

"It will need to be stopped. Perhaps you could call."

"It's already sealed. Preclearance for customs."

"It will need to be stopped," Shan repeated.

Fowler stepped to the phone and minutes later a truck was brought to the office door. Shan paced about it as Kincaid and Fowler watched in confusion from the doorway.

"The 'me' generation," Shan said absently as he studied the shipment crates. "I read it once in an American magazine. They can't wait for anything. They want it all now. With one more murder they would have won. Only the colonel was left. Maybe they were going to take over the mine, too. I think the suspension was partly a response to what Kincaid did with Jao: they wanted to be able to get rid of you if circumstances got out of control. Do you remember what day you received the permit suspension?" he asked Fowler.

"I don't know. Ten days ago. Two weeks."

"It was the day after we discovered Jao's head," Shan said, speaking slowly to let his words sink in. "When they discovered their demon was getting out of control. I don't think they had decided yet whether to get rid of you. They just liked to keep options open. Like planting the computer disks and pretending there was an espionage investigation."

"Tyler," Fowler gasped. "Talk to him. Tell him you don't know-"

"No one," Kincaid insisted, "did anything wrong. We're making history. Then I can go home and get the attention we need. I'll bring back even more investment. A hundred million, two hundred million. A billion. You'll see, Rebecca. You'll be my manager. My chief executive. You'll always understand."

Fowler just stared at him.

Shan began unpacking a box of brine samples, each in its own four-inch-wide metal cylinder. "Something here was made outside. You ordered it from Hong Kong, maybe. The boxes, perhaps."

"The cylinders," Fowler said, barely audible. "Made by the Ministry of Geology."

Shan nodded. "Jao had been trying to find a mobile X-ray machine. He wanted to bring it here, I think, or to the Bei Da Union compound. I believe he expected to find something in the terra cotta statues they were selling or the wooden crates used for shipping. But the Union is smarter than that. I kept wondering, what was the point of advancing your shipping dates?" He unscrewed the lid on one of the metal cannisters and dumped its brine on the ground. "It had to be because they wanted to ship as much as possible before the added security precautions for the American tourists took effect."

He did not know what he sought, but measured the interior depth of the cannister with a long screwdriver retrieved from the truck. The screwdriver's head was barely visible above the rim. He held it along the exterior. It was six inches short of reaching the bottom. For several long moments he examined the cylinder, then finally found a seam, an almost invisible seam. He twisted the container to no avail. Fowler called for two large wrenches. Together they freed the bottom compartment, pulling the ends of the container in opposite directions. Inside was a dark brown, acrid paste.

"This," Shan announced with a nod toward Tan, who stood a hundred feet away, directing the machinery, "is what will make the colonel a hero. Murder is only murder. But smuggling drugs, that is an embarrassment to the state."

Fowler was pale as a ghost. Kincaid stumbled forward. He grabbed another of the cylinders and opened it as Shan had done, then a third. By the fourth he began to shake. He shoved his hand inside and pulled it out, covered with the thick ooze. "The pigs," he moaned, "the greedy little shits."

"As I said, you were the only one who was friendly both with the Bei Da Union and with someone close to the purbas." Shan's hand found the American's khata around his neck and pulled it off. "They fed you information about the victims and you got it to Jansen. Jansen knew the purbas, so he gave it to them and it was recorded in the Lotus Book. But it wasn't meant for the book. It was meant for you. Because they knew you had to believe in what you were doing. You wouldn't do it if you thought it was just to help them advance in office. No. You did it to punish. You did it for your cause. Only with Prosecutor Jao you went too far. It was probably easy to persuade them to entice him to the South Claw. After all, if killing Jao on the 404th's road caused the Tibetan prisoners to react and the knobs to be brought in, your friend the major would always be in control, he could go through the motions without really hurting the Tibetans, right? But the skull shrine. That upset them, because they were taking so much of the gold for themselves. What you did with his head threatened to shut their gold reclamation down. They had to discipline you. Maybe they decided they didn't need you anymore. So they went to the hiding place and incapacitated the costume, then suspended the permit. And when you tried to go back to the costume there were guard dogs. They bit you on your arm. Not a cut from the rocks. A dogbite." He dropped the khata on the ground beside Kincaid and looked at Fowler. What had she called Kincaid? The lost soul who had found his home.

There was still a glimmer of defiance in Kincaid's eyes. "Tamdin is the protector of the Tibetans," he said slowly. "The people have to believe again in the old values. That's all I did, protect the Buddhists. We saved them. We saved the Lhadrung Five."

"What do you mean?"

"They're in Nepal, the others. That was part of the plan. Once they were officially reported as executed, no one would notice if they were actually smuggled across the border. The major got them across. They're all alive."

Shan sighed and reached into his pocket. Only a slender thread remained of the American's delusion. Shan handed him the photographs of the three executions. By the time Kincaid had seen half a dozen he had fallen to his knees. When he looked up it was not to Shan but to Fowler. A dry sob wracked his chest.

"It wasn't about drugs," he cried. "You gotta believe me. If I'd ever thought-"

The tears that streamed down his cheeks seemed to revive Fowler. When she spoke it was as if she were comforting a child. "Then you wouldn't have put on the costume for them, would you, Tyler?"

"It was Hitler. It was Stalin. You know what they have done here. We were going to change it. You would understand, Rebecca. I always knew you would understand. Someday you were going to be proud of me. They can't be forgiven. Someone has to-" He stopped as he saw the revulsion in her face. "Rebecca! No!" he screamed, and collapsed to the ground at her feet, pounding the earth with his fist.

Chapter Twenty-one

The arrests were made swiftly, Colonel Tan reported. Li Aidang, Hu, and Wen Li had been at their private compound, loading boxes of records into their Land Rovers. The major had gone straight to his helicopter, confidently expecting to fly across the border. But Tan had disabled the machine the night before, and staked it out with a hand-picked squad of soldiers. Fifty more of Tan's troops had been sent to search the Bei Da Union's buildings. It took them six hours to locate the vault built into the old gompa's subterranean shrine. It held bank records for Hong Kong accounts, names in Hong Kong, and an inventory of processed opium paste.

Shan worked all night on his report. In the morning, just after dawn, Sungpo and Jigme were released from the warehouse at Jade Spring Camp where Tan had secreted them. He stood at the gate and watched, wanting to say something but finding no words. They did not acknowledge Shan as they passed through the gate. They refused the offer of a ride. Twenty feet down the road Jigme turned and gave him a small, victorious nod.

Two hours later Shan was in Tan's office, dressed in his prison garb. The phone was ringing incessantly. Two young, well-scrubbed officers were assisting Madame Ko.

"The Ministry of Justice has already decided to declare Prosecutor Jao a Hero of the People. A medal will be sent to his family," Tan announced impassively. "They expect arrests in Hong Kong later today. Li talked all night. Tried to make us believe he was in it as part of his own investigation. Gave enough evidence to fill a book. Won't make any difference. A general from the Bureau's office in Lhasa has arrived. They have a special place in the mountains they use for such things. In tomorrow's newspaper the people will be told of a tragic accident on a high mountain road. No survivors."

Shan was looking out the window. The 404th was still not at work.

Tan followed his gaze. "With the bridge gone there's no need for a road," he announced. "The project is terminated."

Shan turned in surprise.

"There is no money for a new bridge," Tan explained with a shrug. "The Bureau troops are already moving back to the border. The 404th will not be punished. It starts a new project tomorrow. Irrigation ditches in the valley." Tan joined Shan at the window for a moment, looking down at the street where Sergeant Feng was leaning against the truck. "You've ruined him, you know."

"Feng?"

"All these years in my command, and now he asks for a transfer. As far from a prison as possible. Says he wants to go see if any of his family is still alive. Says he has to go to his father's grave." Tan gestured awkwardly to a paper bag on the table. "Here. Madame Ko's idea," he said. There was a strange tension in his voice, not the jubilation Shan had expected.

It was a new pair of military boots and work gloves.

Shan said nothing, but sat and began unlacing his shoes. "What about the American?"

Tan hesitated. "Not a problem anymore. The U.S. embassy has already been contacted."

"Deported already?"

Tan lit a cigarette. "Last night Mr. Kincaid climbed the cliff over the skull cave. He secured a rope to his neck and leapt off. The work crew found him there this morning, hanging above the cave."

Shan clenched his jaw. So many lives had been wasted. Because Kincaid had been too hard a seeker. "Fowler?"

"She can stay if she wants. There's a mine to run."

"She'll stay," Shan said as he eased off his shoes and tied the laces together to carry them. He would wear the boots for Madame Ko, and give them to Choje later.

Tan stared at a folded sheet of newspaper with an indecisive air. As Shan pulled on the boots, Tan shoved the paper across his desk.

It was a press report dated ten days earlier. A full-page obituary. Minister Qin of the Ministry of Economy was mourned as the last Eighth Route Army survivor in active government.

"I called Beijing. He left no instructions about you. Big housekeeping already done in his office. Seems lots of people wanted his records destroyed, fast. Files all gone. The new staff, no one's heard of any instructions about you."

Shan folded the sheet into his pocket. It wasn't necessarily good news. With Qin alive, there had at least been someone who remembered him, someone with authority over his tattoo. He wouldn't be the first person to be forgotten in a Chinese prison.

Tan fingered the small brown folder Shan had seen on his first visit. "Right now this is the only official evidence of your existence." Tan closed the folder.

"There was something in Beijing, though." Tan lifted a parcel wrapped in oilskin. "They didn't find a file, but they found this on his desk, like some kind of trophy. Had your name on it. I thought you would-" The words drifted away as he opened it. On the cloth lay a small, worn, bamboo cannister.

Shan stared in disbelief. His eyes moved slowly from the familiar cannister to Tan, who was gazing at it. "I used to watch the Taoist priests," Tan said solemnly. "They would throw the sticks and recite verses to groups of children."

Shan's hand trembled as he reached for it and opened the lid. Inside, the lacquered sticks were still there, the throwing sticks of yarrow used for the Tao Te Ching, passed down from his great-grandfather. Because they had been the only physical possession Shan had valued, the Minister had made a show of taking them away. Slowly, making his hand remember the motion that once had been reflexive, he scattered the sticks in a fanlike movement. He looked up, embarrassed.

"It makes you remember," Tan said with an odd, haunted tone. He looked at Shan, his face narrowed in question. "Things were different once, weren't they?" he asked with sudden emotion.

Shan just smiled sadly. "The set is an heirloom," he said very quietly. "You are kind. I had no idea they had been preserved."

He rolled them in his fingers, surprised by the pleasure of their touch. He gripped them tightly, with his eyes shut, then returned them to the cannister and cradled it in his hands. For the most fleeting of moments there was a faint scent of ginger and he felt his father was near.

"Perhaps," Shan said, "I could ask a great favor."

"I have spoken to the warden. You are to get light duties for a few weeks."

"No. I mean about this." He reverently set the cannister back on the cloth. "It will be confiscated. A guard will throw them in a fire. Or sell them. If you or Madame Ko could keep them, I mean until later."

Tan looked at him with pain in his eyes. He seemed about to speak, then awkwardly nodded and covered the cannister with the cloth. "Of course. They will be safe."

Shan left him there, staring at the sticks.

Madame Ko was waiting, tears in her eyes. "Your brother," Shan said to her, remembering her devotion to the sibling lost so many years ago in the gulag. "I think you have honored him by what you have done."

She embraced him, like a mother would embrace a son. "No," she said, her lip quivering. "It is you who have honored him."

Shan was halfway down the corridor when Tan called out from behind him. He walked slowly, uncertainly, toward Shan. The cannister was in one hand, Shan's official folder in the other.

"I can't do anything officially about a Beijing file," Tan said. "Not even a lost file."

"Of course," Shan said. "We made a deal. It has been honorably concluded."

"So you'd have no travel papers. Not even work papers. You'll be in jeopardy anywhere outside this county."

"I don't understand."

As he spoke Tan's eyes began to shine with a light Shan had never seen in them. He handed the folder to Shan.

"There. You no longer exist. I'll call the warden. You'll be removed from the rolls." Tan slowly extended the cannister, and their eyes locked as though for the first time.

"This land," Tan sighed. "It makes life so difficult." He nodded, as though in reply to himself, then dropped the cannister into Shan's hand and turned back toward his office.

***

Dr. Sung asked no questions. She gave him the fifty doses of smallpox vaccine without a word, then made him wait for a booklet on its administration. "I hear they're gone," she said impassively. "The Bei Da boys. As if they never existed. They say a special clean-up squad came from Lhasa." She found a small canvas bag for the medicine, then followed him into the street as though unable to say good-bye.

She stood, the wind tugging at her smock, while Shan shrugged a farewell. At the last moment she produced an apple. As she stuffed it into his bag he offered a small smile of gratitude.

It would be a long trek to Yerpa.