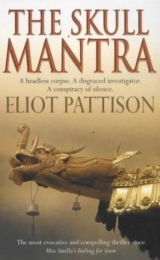

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

He watched, perplexed, then walked toward the woman. She moved away before he reached the wall, not acknowledging him. He stood where she had stood, trying to understand. There was a gap between the buildings that was being blocked with brickwork. The job was not yet completed. He could see over the unfinished wall into an elegant courtyard. There was a man in the attire of a waiter carrying a tray with tall drinking glasses. A large wooden tub with steaming water was partially set in the ground. Two sleek young women in bikini swimsuits were stepping into it.

He slowly turned, confused, and found himself facing the opposite direction. He stared for a moment in shock. There was a low building, a stable converted to a garage. Inside it were two red Land Rovers.

Through the corner of his eye Shan saw Li approaching. He turned and slowly moved along the statue heads, letting Li catch up.

"Is Lieutenant Chang of the 404th part of your Bei Da Union?" he asked.

Li frowned. "I believe he qualified for membership," he said cryptically.

"How about a soldier named Meng Lau?"

Li ignored the question, and moved closer. "Listen, you should become a witness," Li offered. "Surely having the lead in an investigation must be overwhelming for one in your position. Become a cooperative witness instead."

"A witness from the 404th?"

"A witness recently transferred to trusty duties at the 404th, let's say. A model prisoner. I will vouch for you. You are always diligent, you have never been accused of lying, that kind of thing. Your problems have been of a different nature, in Beijing. The tribunal need not know of them."

"But I have nothing to say." Shan kept walking. There was a pool in one corner of the courtyard. It was made of stone blocks, elegantly carved centuries before, and was populated with small silver fish. Lotus blossoms floated in it, and an empty beer bottle.

"You might be surprised at what you could say," Li said from behind.

Shan walked to the edge of the pool and turned. "You haven't described the nature of your corruption investigation." From his perspective he could see a small knoll just beyond the compound. On it was a magnificent seated Buddha, at least twenty feet high. It had an unfamiliar headdress. Shan recognized it with a start. Someone had bolted a satellite dish to the head of the Buddha.

Li moved to his side and bent toward his ear. "Irregularities in the prison accounts. Unexplained withdrawals from state accounts. Missing military assets."

"Are you saying that Tan and the warden are conspirators? You're implicating the warden?"

"Would you like him to be implicated?"

Shan stared, wondering if he had heard correctly. "I would need to see your files."

"Impossible."

"Let me speak to Miss Lihua."

"Jao's secretary? Why?"

"Let her confirm Jao's corruption investigation. She would know."

"You know she is on vacation." Li shrugged as he saw the frustration on Shan's face. "All right. You can send a fax."

"I don't trust faxes."

"Okay, okay, as soon as she returns." He glanced at his watch. "The car will return you to town."

Shan climbed into the car without looking back. He knew Li was lying when he said he didn't want Shan to be a victim. But was he lying because he was worried about the investigation or just for all the usual reasons?

Li leaned into the window. The sneer was gone from his face. "Damn you, Shan. I don't know why I'm telling you this. It's worse than you could ever imagine. Heads are going to roll and no one will be there to protect yours. You have to go back to the 404th and I have to get my case done before the madness starts."

"The madness?"

"They're opening an espionage case. Someone in Lhadrung has stolen computer disks containing secrets of the Public Security border defenses."

***

Shan watched Dr. Sung march past Yeshe sitting on the bench in the corridor and into her dimly lit office. She threw her clipboard on a chair, switching on a small desk lamp, and pushed aside a plate of old, half-eaten vegetables. She hit a button on a small cassette player and turned to a chessboard. It was in the middle of a game. Opera music began to play. She moved a pawn, then spun the board about. She was playing against herself.

After two moves she stopped and looked out at the bench. Muttering angrily, she twisted the lamp upward, illuminating Shan's chair in the corner.

"The most fascinating thing about investigations," Shan observed with great fatigue, "is discovering how subjective truth really is. It has so many dimensions. Political. Professional. But those are easy to discern. What is hardest is understanding the personal dimension. We find so many ways to believe in the lies and ignore the reality."

The doctor switched off the music and stared absently at the chessboard. "The Buddhists would say we each have our own ways of honoring our inner god," she observed, with a choke in her voice.

The words shook Shan. Suddenly he did not know what to say. He wanted most of all to let her go, to leave the woman to her peculiar misery, but he could not. "When did you stop honoring yours?"

He yearned for one of her sharp, angry comebacks, but all he got was silence.

Unfolding Sung's letter to the American firm, he dropped it in front of her. "Did you feel you were lying to me when you pretended to know nothing about Jao's interest in an X-ray machine? Or did you really believe yourself because only your name was on the official record?"

"All I said was that it was too expensive."

"Good. So you didn't mean to lie."

Sung absently moved a castle. "Jao asked me to write a letter. No one would suspect such a request from a clinic."

"Why would he need to hide it? Why not just ask himself?"

She picked up a knight and stared at it. "An investigation."

"He would have wanted your help to operate it. He didn't say where he would need it?"

She still stared at the chess piece. "Sometimes he would come, not very often, and we would sit here and play chess. Talk about things at home. Drink tea. It felt like, I don't know. Civilized." She put both hands on the knight and twisted it as though to break it.

"So you wrote the letter to help in an investigation. To find something that was hidden."

"It would be so easy to be like you, Comrade Shan, just to ask questions. But I told you before, there are questions that may not be asked. All you have to do is ask about other people's truth. Some of us have to live it."

"A murder investigation?" Shan pressed. "Corruption? Espionage?"

Sung laughed weakly. "Espionage in Lhadrung? I don't think so."

"What was he going to use the machine for?"

Sung shook her head slowly. "He wanted to know if it would fit in one of his four-wheel-drive trucks. He wanted to know the power source it would require. That's all I know."

"Why wouldn't you ask? He was your chess partner."

"That's why." Sung opened her hand and stared forlornly at the knight. "I assumed he wanted it to open one of their tombs. And if I knew that I could not let him sit here again."

***

The 404th was like a cemetery. The faces of prisoners, gaunt and expressionless, peered out of the barracks. The patrols which kept them confined to quarters marched stiffly through the compound. The soldiers kept looking over their shoulders.

The stable was in use. Shan could tell– not because there were screams. There were never screams from the Tibetans. Nor because of greater activity in the infirmary. He could tell because an officer walked by carrying rubber gloves.

A cloud seemed to have settled over Sergeant Feng as he moved through the gates with Shan. He did not speak to the knobs on guard at the dead zone but looked straight ahead until they reached the hut, then opened the door for Shan and stood to the side gesturing him awkwardly inside.

The scene was much as it had been when he left the hut six days earlier. Trinle lay in bed, prostrated by fatigue, a blanket covering his head and most of his body. The others sat on the floor in a circle, taking instruction from one of the older monks.

Choje Rinpoche had braced his knees and back with a gomthag strap torn from his blanket, so he would not fall while meditating. One of the novices held a rag to the back of Rinpoche's skull. It came away pink with blood.

It took several minutes for him to acknowledge Shan's inquiries. His eyes fluttered, then opened wide and brightened. He surveyed the hut with an intense, curious gaze, as though to confirm which world he was in. "You are still with us," he said, not as a question but as a declaration of welcome.

"I need to know something about Tamdin," Shan said, fighting the knot that was tying in his gut. It seemed he felt the lama's pain more than Rinpoche himself. "Rinpoche," he asked, "what if Tamdin had to choose between protecting the truth and protecting the old ways?"

Of all the paradoxes that riddled his case, the one that troubled him most was that of the killer's motives. Tamdin was protector of the faith, and his victims defiled the faith. But how could such a killer then let innocent monks die for his crimes? That was defiling the faith, too.

"I don't think Tamdin chooses. Tamdin acts. He is conscience with legs."

And flaying knife, thought Shan.

"Like conscience with legs," the lama repeated.

Shan considered the words in silence.

"When I was young," Choje offered, "they said there was a man in a nearby village who prayed for Tamdin's help and never received it. He renounced Tamdin. He said Tamdin was a tale created for the dancers in the festival."

"I haven't met many recently who would call Tamdin a fiction."

"No. Fiction is not the word to describe him." Choje held his clenched fingers before Shan's face. "This is my fist," he said, then threw his fingers out. "Now my fist does not exist. Does that make it a fiction?"

"You're saying in certain moments anyone can become Tamdin?"

"Not anyone. I'm saying the essence of Tamdin may exist in something that is not always Tamdin."

Shan recalled the last time they had spoken about the demon protector. Just as some are destined to achieve Buddhahood, Choje had said, perhaps some are destined to achieve Tamdinhood.

"Like the mountain," Shan said quietly.

"The mountain?"

"The South Claw. It is a mountain but it hides something else. A holy place."

"It is such a small piece of the world we have," Choje said, speaking so low Shan was forced to lean toward his mouth.

"There are other mountains, Rinpoche."

"No. It's not that. This-" he said, gesturing around the hut. "The world does not take notice of us. There is so much time before, and after. So many places. We are a mote of dust. No one outside should care about us. Only we should care about us. Our particular being occupies this place for now. That is all. It is not much, really."

The words chilled Shan. Something terrible was going to happen. "You're never going back to the mountain, are you?" He looked up with dread in his face. "No matter what happens. You can't have the road built. That is what it's all about." Why was it so important? Is that where he had gone wrong, not paying enough attention to the secret of the mountain?

"Waking up every day for fifty years, for a hundred years, is no great accomplishment, after all," Choje said with a serene smile. "It is like arguing that your mote of dust is bigger than my mote of dust. They are the arguments of an incomplete soul."

They would bring others to build the road, Shan wanted to say. But he did not have the courage.

"We have talked. All of us. Everyone has agreed. Except for a few. Some with families. Some who have another path to follow."

Shan looked around. The khampa was gone.

"They have received our blessings. They were accepted across the line this morning. Those of us who are left…" Choje said with his peaceful smile. He shrugged. "Well, we are the ones who are left. One hundred eighty-one. One hundred eighty-one," he repeated, still smiling.

The whistle for exercise blew, then another, and another, in relays through the camp. The men began to stir, without talking, toward the door.

"It is time, Trinle," Choje called with new strength, and the figure in the blanket rose. Not taking his eyes off Choje, Shan sensed Trinle struggling to his feet. With a shudder he realized that Trinle must have been in the stable. From the corner of his eye he saw the stooped figure wrap the blanket around his makeshift robe and over his head like a hood, then shuffle to the door.

Only Shan and Choje remained in the hut. They sat in silence amid the brilliant shafts of light that leaked through the loose boards of the walls and roof.

"What happened to that man? The one who didn't believe?"

"One day part of the mountain above him collapsed. It destroyed everything. The man, his children, his wife, his sheep. And worse."

"Worse?"

"It was strange. Afterward, no one could remember his name."

Suddenly there was a peculiar swelling of sound from outside– not a shout, but a rapidly rising murmur that carried through the camp. Shan helped Choje to his feet.

They found the prisoners in the small yard behind the hut, or rather around the small yard, packed two and three deep around an empty space twenty feet in diameter.

"He's gone!" exclaimed one of the monks as they approached. "The magic…" he began, but seemed unable to complete the sentence.

"Like the arrow! I saw it. Like a blur!" someone shouted.

The line parted to let Choje through, Shan at his side.

"Trinle!" one of the young monks gasped. "He's done it!"

There was nothing in the clearing but Trinle's shoes, sitting side by side as if he had just stepped out of them.

No one breathed. Shan stared, stunned. It had the quality of a strange, poorly timed joke at first. He looked up with alarm as it sank in. Trinle was gone. Trinle had escaped. He had spirited himself away, after all the years of trying.

The monks stared reverently at the shoes. Some dropped to their knees and offered prayers of gratitude.

But the spell did not last long. From somewhere the whistle began to blow, signaling the end of the exercise period. From the back a man with a deep baritone voice began to chant. Om mani padme hum. He continued, solo, for perhaps thirty seconds, then was joined by another, and another, until soon the entire group joined in, drowning out the angry whistles.

The prisoners began to move into the central yard, celebrating the miracle with their mantra. Shan found himself moving with them, beginning the chant. Suddenly a hand seized his elbow and pulled him to the side. Sergeant Feng.

They stayed there, watching, as the prisoners arranged themselves in a large square and sat, still chanting loudly.

Instantly the knobs were among them. Shan could see the soldiers shouting, but their voices were lost in the reverberating mantra. He tried to pull away but Feng held him with an iron grip. The batons were raised and the knobs began slowly, methodically, to beat the prisoners on their shoulders and backs, swinging their batons up and down as if cutting wheat with sickles.

The batons had no effect.

A Public Security officer appeared, his face a mask of fury. He screamed into a bullhorn, but was ignored. He grabbed a baton from one of his men and broke it over the head of the nearest monk. The man slumped forward, unconscious, but the chanting continued.

He threw the stump of the baton to the ground and moved along the ranks. The scene unfolded as if in slow motion.

"No!" Shan shouted and twisted in vain against Feng's grip. "Rinpoche!"

The officer paced around the entire square, then ordered two knobs to drag a monk to the center. It was one of the younger men, from another hut. The monk had shaved his head and wore a red band on his arm. He continued chanting, still kneeling, seeming not to notice the knobs. The officer stepped behind him, drew his pistol, and fired a bullet through his skull.

Chapter Fifteen

Sergeant Feng had stopped speaking. As they drove out of the base onto the Dragon's Claw he gripped the wheel with both hands, a distant, desolate look on his face. He only grunted when they pulled into the turnout above the ancient suspension bridge. He did not argue this time, nor did he try to follow as Shan and Yeshe crossed over the span, each carrying small drawstring bags with a day's provisions.

The air was unusually still, without the wind that almost always rose with the sun. Shan surveyed the slope ahead with the binoculars. He still was not certain what to look for or where to go, only that the mountain still held a vital secret. There was no sign of the sheep that might have led him to the enigmatic young herdsman. Perhaps he needed to return to the ledge with the chalk symbols. Then, at the southern end of the ridge, he spotted a patch of red among the early morning shadows. Once he had the pilgrim in the lenses, he could see the man was moving along the track at a remarkably fast pace, rising, standing, kneeling, and dropping in the act of kjangchag, the prostration of the pilgrim, as though the movements were calisthenics.

"I still don't know what it is we seek," Yeshe said at his side.

"I don't either. Something out of the ordinary. The pilgrim, maybe."

Yeshe shrugged. "Each time we've been here we've seen a pilgrim. In Tibet it's ordinary as rain."

"Which makes it a perfect camouflage." Shan suddenly saw what had been eluding him. "Let's go," he called out, still not certain of anything except that he wanted to know where the pilgrim was going.

They moved at a half trot along the ridge, keeping the pilgrim in sight. After an hour they had nearly caught up, and rested as they watched the figure begin its descent of the ridge toward the valley beyond.

The red robe arrived at the bottom of the ridge and disappeared behind a long formation of rocks. Shan and Yeshe shared a bottle of water and waited for the pilgrim to reappear on the other side of the rocks.

"My mother made a pilgrimage," Yeshe said. "After my sister died. I was away at the monastery already. She went to Mt. Kalais," he continued. "The sacred mountain. It was a bad time. Late blizzards in the mountains. Troop movements because of the uprising."

"Such challenges add to the accomplishment."

"We never saw her again. Someone said she became a nun, others that she tried to cross the border. I think it was probably simpler."

"Simpler?"

"I think she just died."

Shan didn't know what to say. He offered Yeshe the bottle and picked up the glasses. "He hasn't come out," he observed. Feng had loaned him his wristwatch for the day, which Shan stared at in confusion. "How long since he went behind that rock?"

"Ten, fifteen minutes."

Shan leapt up and began trotting down the slope, leaving Yeshe still holding the bottle in his outstretched hand.

He intercepted the pilgrimage trail, worn by centuries of use, as it wound its way through the boulders and emerged into the rolling heather of the high valley. By the time Yeshe caught up, Shan had scouted past the rocks and retraced the route looking for a second trail, a cutoff, to no avail.

Minutes later Yeshe called out and pointed to a small hole, a low, six-foot-long tunnel created by a slab that had collapsed between two sheer rock walls. It was barely wide enough to crawl into. But by the time Shan arrived and bent to look into it, Yeshe had disappeared.

The hole, he discovered, did not end in six feet, but jogged at a sharp right angle to the left. Shan squeezed inside, following Yeshe's dim shape for fifty feet before the roof rose, then disappeared entirely. They were in a narrow, twisting passage between the rock walls, which they followed into a small canyon.

"We are not supposed to be here," Yeshe whispered nervously. "It is a holy place. A very secret place. It is protected…"

His words drifted away, his tongue silenced by the power of the scene before him. A sheer rock face, five hundred feet high, rose opposite them, a stone's throw away. Diamond-bright blades of sunlight cut through the canyon shadows, heightening the sense of elevation. A hundred feet up the wall were five large rectangular holes, windows, carved out of the rock. Three other smaller openings, obviously manmade, were arrayed above the five, leading to a final smaller opening nearly three hundred feet above them. Brilliantly colored horse-flag banners, thirty feet long and emblazoned with sacred symbols, hung from poles extended from the five windows, flapping in the wind.

The Dragon Claws, Shan realized, were about to give up their secret.

"Into the shadows!" Yeshe cautioned, stepping behind a rock as though to hide. "There is someone at the water."

Shan peered toward the end of the canyon, where a shimmering pool of water reflected the images of the flags. Under a solitary willow tree at the end of the pool sat a lone figure, his back to them.

"We are not supposed to find this place," Yeshe warned again. "We should go. We can ask permission from the old-"

"There is no time for permission," Shan said, and moved toward the pool. There were small irises growing among the rocks, and a flock of birds at the water's edge.

"Not everyone is glad that you came," the figure said when Shan was ten feet from its back. It did not turn. The water and the rock gave a strange resonance to what was the voice of a child. "But I had hoped we would meet again. They say things about you I do not understand. Now we can speak once more."

"Your sheep have lost you again, I see," replied Shan.

The youth turned about slowly, wearing a grin. "Welcome to Yerpa."

Shan gestured to Yeshe, who stood behind him. "This is-"

"Yes. I have been told. Yeshe Retang. You may call me Tsomo."

He rose and silently led them back toward the passage they had just left, then veered to the canyon wall where he entered a narrow cleft obscured by the shadows. Tsomo led them for twenty paces through the darkness, until they reached a dim butter lamp at the bottom of a winding stairway carved out of the living rock.

They climbed the steps until Shan's feet ached; they rested, then climbed further. Along the corridor were several low doors leading to darkened chambers. From one came the sound of a solitary prayer, from another a fetid smell and an abject groan. At last they reached a large chamber lit by a single long window and dozens of candles.

The walls were covered with murals, paintings of guardian deities and the past and future Buddhas. It was not the chapel Shan had expected. It was far smaller, and he began to understand that he was not in a gompa at all, but in another type of holy place he did not recognize. A solitary man in the robe of a monk was on the floor, tapping a tapered metal tube from which vermillion sand fell. He sat at the edge of a six-foot-wide circle, most of which had been filled with intricate shapes and geometric designs composed of colored sands. The unfinished portion where he sat was inscribed with chalk.

"This is the Kalachakra mandala," Tsomo explained. "A very old style."

The sand painting was in concentric rings which led to square lines depicting the walls of three palaces, one inside the other. Inhabiting the palaces were scores of deities presented in minute detail.

"It is about the evolution of time," Tsomo continued, "the folding of time, because Buddha cannot bear to abandon a single soul, so that time continues in a great circle until all beings are enlightened."

Shan knelt reverently at the edge of the sand. The monk bowed his head toward him and continued working, building the mandala one particle at a time.

"Seven hundred twenty-two deities," Yeshe said behind him in a hushed tone. "They used to do this in Lhasa every year, for the Dalai Lama."

"Exactly," Tsomo said enthusiastically, pulling Yeshe forward for a closer look. "Dubhe trained with an old lama from the Potola. When it is completed it will have all the traditional deities, each one different, each in the prescribed position. Dubhe has worked on it for three years now. In four or five months he will finish. We will consecrate it, and celebrate its beauty. Then he will destroy it and start again with fresh sand." Tsomo gestured to shelves of rough-hewn timbers that lined the lower walls. They held scores of small clay jars. "Some of the sand from each mandala ever made here has been kept. It is very sacred, very powerful."

They continued along a corridor to a bigger room lit by four windows, more of the rectangular openings they had seen from below. The chamber held wide, sloping tables of rough wood along its perimeter, most of which were empty. Three monks and a nun were at work, each surrounded by butter lamps and containers of brushes and ink stones.

Shan saw the look of deference from those at the tables as Tsomo approached, and the nervous way they studied Shan and Yeshe. They had been prepared to receive strangers, but clearly were uncertain how to react. They chose silence, letting Tsomo explain the elegant manuscripts they were transcribing, writing from ancient bamboo tiles and tattered prayer books onto long narrow pages that, in the traditional style, would not be bound but covered with silk wrappers. Above the tables were shelves holding scores of similar silk packages. They were called potis, Trinle had told Shan once, books wrapped in robes. At one table a monk sat not with brushes but with long chisels and gouges. He was carving the long boards between which the potis were tied. Shan paused at the table, surprised not by the intricate detail of the birds and flowers the monk was carving, but because the man could create such beauty despite the fact that one of his thumbs was missing.

The nun rose and wandered toward them. "The history of every gompa in Tibet," she said, gesturing to the far wall. Her voice was rough, as though from lack of use. "There are letters from the Great Fifth to the kenpos announcing funds for new chapels. There are the original plans for the rope bridge across the Dragon Throat."

Tsomo pulled Shan by the arm as the nun led an awestruck Yeshe along the manuscripts, away from the door. They moved up more steps to an inner chamber deep inside the mountain. It had the air of a classroom. There were only two lamps in the room, both on a small altar. At the far end were shelves of pottery, most of which was broken; above the pottery were symbols painted on the wall. There was a carpet on the floor, and seat cushions on which two monks sat.

One of the monks was facing away from them toward the altar. The other, an older, austere man with twinkling eyes, greeted them with a slight bow from his waist. "You are most persistent, Xiao Shan," the monk said in Mandarin. There was the sound of bare feet scampering behind him. Three boys in the robes of students moved inside and sat behind the monk who spoke. They looked at Shan with round, bewildered expressions.

"You have presented us with quite a dilemma, you know," the old lama continued.

"I am only investigating a murder." Shan's eyes moved back to the symbols above the pottery. With a start he realized he had seen them before, made in chalk at the ledge above the Dragon Throat Bridge.

"Yes. We know. The prosecutor was killed not far from here. Sungpo the hermit is detained. The 404th is on strike. Seventeen priests have been tortured. A prisoner has been executed. The Public Security Bureau is poised for another atrocity."

"You know more about the 404th than I do," Shan said in wonder. "Are you the abbot of this place?"

The man's smile seemed to cover his entire face. "There is no abbot here. My name is Gendun. I am just a simple monk." As he spoke his fingers worked rosary beads carved of dark reddish wood. "Will they send you back there, when it is done?"

Shan paused, considering the man, not the question. "Unless they choose a worse place."

Another boy appeared with a pot of buttered tea and filled bowls in silence. From somewhere came the sound of tsingha, the tiny, chimelike cymbals of Buddhist worship.

"You said I was a dilemma," Shan said as he accepted one of the bowls.

"Yerpa is the secret room of a house never seen, built in a land of shadow. Three hundred years ago one of our scholars wrote that in a book." Gendun paused and smiled at Shan. "We write books for each other sometimes, since no one else can see them. He said we were between worlds here. A stopping-over place. Not of the earth, not of the beyond. He called it the mountain of dreams."

"The eye of the raven," the other priest said, still with his back to them. Something in his voice sounded familiar.

Tsomo smiled. "In the library there is a poem, about the dead of winter. Among a hundred snowy mountains, it says, the only thing moving is the eye of the raven."

Shan realized that Gendun was looking at Feng's wristwatch. Shan extended his arm.

"What do you call this?" the monk asked.

"A watch. A small clock." Shan removed it and handed it to him.

Gendun looked at it with wonder in his eyes and held it to his ear. He smiled and shook his head. "You Chinese," he grinned, and handed it back.

Tsomo left his side with a small reverent bow, and knelt beside the second monk, who still faced the altar.

"Even before the armies came from the north this place was known only to the few who needed to know," the old monk continued. "The Dalai Lama. The Panchen Lama. The Regent. It is said to be one of the caves of the great Guru Rinpoche," he said. "It is a world in itself. Usually those who come never leave. It was as you see it five hundred years ago. It will be like this five hundred years from now," he said with absolute confidence.

"I am sorry. But if we do not go back soldiers will come. We mean no harm."

"The tunnel can be sealed against searchers. It has been done in the past. For years at a time when necessary."

"He could teach us the way of the Tao," Tsomo interjected. "We could better understand the books of Lao Tze."

"Yes, Rinpoche. It would be wonderful to have such a teacher." Gendun turned to Shan. "Are you able to teach these things?"

Shan did not hear until he was asked the second time. The monk had called the boy Rinpoche, the term for a venerated lama, a reincarnated teacher. "An old abbot once said to me, 'I can recite the books. I can show you the ceremonies. But whether you learn them is up to you.' "