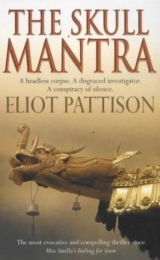

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"But your wife. I thought you went to Shigatse with her."

The old man smiled. "I did. Funny thing, two days after I got home, my wife's time came."

Shan stared at him in disbelief. "I am-" I am what, he considered. Heartbroken? Furious? Paralyzed by the helplessness of it all? "I am sorry," he said.

Lokesh shrugged. "A priest told me that when a soul gets ripe, it will just pop off the tree like an apple. I was able to be with her at her time. Thanks to you." He put his arms around Shan again, stepped back and pulled a small ornamental box from around his neck. It was an old gau, the container for Lokesh's charms. He placed its strap over Shan's head.

"I can't."

Lokesh put his finger to his lips. "Of course you can." He looked at the nun. "There is no time to argue."

The nun was looking back into the shadows, where they had left the scar-faced purba. Her eyes were wet when she turned to Shan. "You have to help, you have to stop him."

Shan was confused. "He said he would not commit violence."

The nun bit her lip. "Only on himself."

"Himself?"

"He wants to go to the mountain, to do the prohibited rites and turn himself over to the knobs." Her hand clamped around his arm as he stared back into the shadows of the underground labyrinth, comprehending at last. The scar-faced purba was the fifth, the last of the Lhadrung Five, and the next to be accused of murder if the conspiracy continued.

Lokesh gently pulled the nun's hand away and moved Shan toward the table. "The 404th is troubled again. We need your wisdom once more, Xiao Shan."

Shan followed Lokesh's gaze to the book on the table. It had the dimensions of an oversized dictionary, and was bound with wood and cloth. It was a manuscript, with entries in several hands, even several languages. Tibetan mostly, but also Mandarin, English, and French.

The nun looked up with deep, sad eyes. "There are eleven copies of this in Tibet," she said quietly. "Several more in Nepal and India. Even one in Beijing." She moved to the side and gestured for Shan to sit at the table. "It is called the Lotus Book."

"Here, my friend," Lokesh said excitedly as he turned to the front pages of the book. "It was such a wonderful time to be alive in those days. I have read these pages fifty times and still sometimes I weep with joy at the memories they preserve."

The pages were not uniform. Some were lists, some were like encyclopedia entries. The very first word in the book was a date. 1949, the year before the Communists began to liberate Tibet.

"It is a catalog of what was here before the destruction," Shan spoke in awe. It wasn't just lists of gompas and other holy places, it also held descriptions of the numbers and names of monks and nuns, even the dimensions of buildings. For many sites, first-hand narratives by survivors had been transcribed, telling of life at the place. Lokesh had been writing when Shan entered the room.

"The first half, yes," the nun said, then opened the pages to a silk marker where another list began.

It was an inventory of people, a list of individual names. Shan felt a choking sensation as he read. "These are all Chinese names."

"Yes," Lokesh said, suddenly more sober. "Chinese," he whispered, then his arms slackened and he fell still as if he had suddenly lost his strength.

The nun bent over the book and turned to the back, where the most recent transcriptions had been made. One by one, she pointed out names to Shan as he stared in a mixture of horror and disbelief. Lin Ziang was there, the murdered Director of Religious Affairs, as was Xong De, the deceased Director of Mines, and Jin San, the former head of the Long Wall collective. All victims of the Lhadrung Five.

Forty minutes later they returned him in the wheelchair, blindfolded, creaking down corridors hewn from the stone, then onto the smooth floors of the clinic, turning so many times he could not possibly have retraced the route. Suddenly, with the sound of the bells again, the scarf that had covered his eyes was untied and he was in the front corridor, alone.

Yeshe was still on the phone, arguing with someone. He hung up when he saw Shan. "I tried every combination. Nothing seems to work." He handed the paper back to Shan. "I wrote down other possiblities. Page numbers. Coordinates. Specimen numbers. Product numbers. Then I thought to call about his travel plans. There's a travel office for government officials in Lhasa. I called to confirm what they said about his trip."

"And?"

"He was going to Dalian, all right, with a one-day stopover in Beijing first. But no other arrangements for Beijing. No Ministry of Justice car to pick him up."

Shan gave a slow nod of approval.

"When you didn't return I went on to other things. I called that woman at Religious Affairs. Miss Taring. She told me she would check the audits of artifacts herself and to call back. When I did, she said one was missing."

"A missing audit report?"

Yeshe nodded meaningfully. "For the audit done at Saskya gompa fourteen months ago. Shipment records show everything went to the museum in Lhasa. But there was no accounting in her records for what was actually found. A breakdown in procedures."

"I wonder."

Yeshe seemed to puzzle over Shan's reaction, then offered more news. "And I tried that Shanghai office."

"The American firm?"

"Right. They didn't know Prosecutor Jao. But when I mentioned Lhadrung they remembered a request from the clinic here. Said there was some correspondence."

"And?"

"Lots of static, then the line went dead." He paused and pulled a sheet of paper from under the blotter. "So I went to the office here. Said I had to check their chronological files. Found this, from six weeks ago." He handed Shan the paper.

It was a letter from Dr. Sung to the Shanghai office, asking if the firm would provide a portable X-ray unit on approval, to be returned in thirty days if found not to be compatible with the clinic's needs.

Shan folded the paper into his notebook. He moved toward the exit, and broke into a trot.

***

Madame Ko led them to a restaurant beside the county office building. "Best to wait," she said, gesturing to an empty table near the rear, beside a door guarded by a waiter holding a tray in arms folded across his chest.

Sergeant Feng ordered noodles; Yeshe, cabbage soup. Shan sipped tea impatiently, then after ten minutes stood and moved to the door. Madame Ko intercepted him, pulling him back. "No interruptions," she scolded, then saw the determination in his eyes. "Let me," she sighed, and slipped behind the door. Moments later half a dozen army officers began to file out, and she opened the door for Shan.

The room stank of cigarettes, onions, and fried meat. Tan sat alone at a round table, smoking as the staff cleared away dishes. "Perfect," he said, exhaling sharply through his nostrils. "You know how I spent the morning? Being lectured by Public Security. They may decide to report a breakdown in civil discipline. They note my abuse of investigation procedures. They have recorded that security at Jade Spring Camp has been breached twice in the last fifteen years. Both times this week. They say one of my cell blocks has been turned into a damned gompa. They hinted about an espionage investigation. What do you know about that?" He drew on the cigarette again and exhaled slowly, watching Shan through the cloud of smoke. "They say their units at the 404th will begin final procedures tomorrow."

Shan tried to conceal the shudder that moved down his spine. "Prosecutor Jao was killed by someone he knew," he announced. "A colleague. A friend."

Tan lit another cigarette from the butt of the first and stared silently at Shan. "You have proof finally?"

"A messenger came that night with a paper." Shan explained what had happened at the restaurant, without disclosing the messenger's identity. Tan would never accept the word of a purba against that of a soldier.

"It proves nothing."

"Why wouldn't the messenger give the paper to Jao's driver? Everyone knew Balti. Everyone gives messages to drivers. It is the custom. Balti was right outside with the car. They were going to the airport."

"Perhaps this messenger didn't know Balti."

"I don't believe that."

"Then by all means we'll release Sungpo," Tan said acidly.

"Even if he didn't know Balti, the waiters would have sent him to the car. The waiter intercepted him assuming that was what Jao would want. But instead, Jao expected something, or recognized something, something that required his instant attention. So he spoke with the messenger. Away from the waiter. Away from his table where the American sat. Away from Balti. And he heard something so urgent that despite his orderly nature he broke his schedule."

"He knew Sungpo. Sungpo could have sent the message," Tan said.

"Sungpo was in his cave."

"No. Sungpo was on the South Claw, waiting to kill."

"Witnesses would say that Sungpo never left his cave."

"Witnesses?"

"This man named Jigme. The monk Je. Both have made statements."

"A gompa orphan and a senile old man."

"Suppose it was Sungpo who sent the message," Shan offered. "Prosecutor Jao wouldn't go to some remote location alone, unprotected, to meet a man he had imprisoned. There was nothing any monk could say to get Jao to act that way. He was anxious to get to the airport."

"So someone helped Sungpo. Someone lied."

Shan stared at the colonel with a grin of victory.

"Shit," Tan muttered under his breath.

"Right. Someone he trusted lured Jao with news he could use on his trip. Information that would help him in his secret investigation. Something he might use in Beijing. We have to find out about it."

"He had no business in Beijing. You saw the fax from Miss Lihua. He was just passing through to Dalian." Tan watched the ashes of his cigarette build a small hill on the tablecloth.

"Then why would he arrange to stop for a day there?"

"I told you. A shopping trip. Family."

"Or something about a Bamboo Bridge."

"Bamboo Bridge?"

"It was on a note in his jacket."

"What jacket?"

"I found his jacket."

Tan's head snapped up with a flash of excitement. "You found the khampa, didn't you? You told the assistant prosecutor you didn't, but you did."

"I went to Kham. I found the prosecutor's jacket. That was the best we could do. Balti was not involved."

Tan offered an approving smile. "Quite an accomplishment, tracking a jacket into the wilderness." He snuffed out his cigarette and looked up with a more somber expression. "We asked about your Lieutenant Chang."

"Did someone recover his body?"

"Not my problem."

Another sky burial, Shan thought. "But he was army. One of yours."

"That's the point. He wasn't PLA. Not really."

"But he was in the 404th."

Tan silenced him with a raised palm. "Fifteen years in the Public Security Bureau. Transferred to the PLA rolls just a year ago."

"That doesn't make sense," Shan said. No one left the elite ranks of the knobs to join the army.

Tan shrugged. "With the right patron it could."

"But you knew nothing about it?"

"The transfer was entered into the army books two days before he arrived here."

"It could be something else," Shan suggested. "He could have still been working for someone in the Bureau."

"Nonsense. Without me knowing?"

Shan just stared in reply.

Tan clenched his jaw and let the words sink in. "The bastards," he snarled.

"Where did Lieutenant Chang serve before?"

"South of here. Border security zone. Under Major Yang."

So he had a name after all, Shan thought. "What do you know about this Major Yang?"

Tan shrugged. "Hard as a rock. Famous for stopping smugglers. Takes no prisoners. Be a general some day."

"Why, Colonel, would such an esteemed officer bother to personally make the arrest of Sungpo?"

Tan's brows furrowed. "You know this?"

Shan nodded.

"A man like that goes anywhere he wants," Tan said, sounding unconvinced. "He doesn't report to me, he's Public Security. If he wants to help the Ministry of Justice, I can't stop it."

"If I were conducting a Bureau investigation I don't think I would parade around the county in a brilliant red truck or buzz the countryside in a helicopter."

"Maybe you're just bitter. I seem to recall that your warrant for imprisonment was signed by Bureau headquarters. Qin ordered it, but the Bureau made it happen."

"Maybe," Shan admitted. "But still, Lieutenant Chang tried to kill us. And Chang was probably working for the major."

Tan shook his head in uncertainty. "Chang's dead, and you still have a job to get done." He rose as though to leave.

"Have you heard of the Lotus Book?" Shan asked, stopping Tan at the door. "It's a work of the Buddhists."

"The luxury of religious studies is not available to me," Tan said impatiently.

"It is more of a catalog," Shan said in a hollow tone. "They started writing it twenty years ago. A catalog of names. With places and…"– he searched for a word-"events."

"Events?"

"In one section the names are nearly all Han Chinese. Under each name is a description. Of his or her role in destroying a gompa. Of participating in executions. Or looting shrines. Rapes. Murders. Torture. It is very explicit. As it is circulated it is expanded and updated. It has become something of a badge of honor, to add your name to its list of authors."

Tan had stiffened. "Impossible!" he flared. "It would be an act against the state. Treason."

"Prosecutor Jao was in the book. For directing the destruction of the five biggest gompas in Lhadrung County. Three hundred twenty monks disappeared. Another two hundred were shipped to prisons."

Tan slipped into a chair, a new excitement on his face. "But that would be proof. Proof that he was targeted by the radicals."

"Lin Ziang of the Religious Bureau is in the book," Shan continued. "Twenty-five gompas and chortens destroyed at his command in western Tibet. Directed the transportation of an estimated ten million dollars' worth of antiquities to Beijing where they were melted down for gold. Came up with the idea of alloting nuns to military installations for entertainment. Xong De of the Ministry of Geology was in there. Commanded a prison when he was younger. He had a prediliction for thumbs."

"I want it!" Tan bellowed. "I want those who wrote it."

"It does not exist in one volume. It is passed along. Copies are transcribed by hand. It is all over the country. Even outside."

"I want those who wrote it," Tan repeated, more calmly. "What it says is unimportant. Just history. But the act of writing it-"

"I would have thought," Shan interrupted, "that just the one investigation was more than we could handle."

Tan pulled out a cigarette and tapped it nervously on the table, as if conceding the point.

"I know prisoners in the 404th," Shan continued, "who can recite the details of atrocities committed in the sixteenth century by the pagan armies which attacked Buddhism, as if it happened yesterday. It is a way of keeping the honor of those who suffered, and keeping the shame of those who committed the acts."

Tan's anger began to burn away. He did not, Shan suspected, have the strength for more than one battle at a time. "This is your proof that the killings were connected," he observed.

"I have no doubt of it."

"But it just proves my point about the destablizing force of the minority hooligans."

"No. The purbas wanted me to know about it to protect themselves."

"What do you mean?"

"They want us to solve the murders, too. They realized that if the Bureau found out about the book and thought it was connected to the killings, it would be used to destroy them. There's still one more of the Lhadrung Five left. One more murder to frame him for. And if someone in the top rank is assassinated, the knobs will move in permanently. Martial law. It would set Lhadrung back thirty years."

"Top rank?"

"There was another name in the book," Shan said. "Listed for elimination of eighty gompas. Destruction of ten chortens to construct a missile base. Responsible for the disappearance of a truckload of khampa rebels being transported to lao gai. In April 1963."

"It's the only other Lotus Book name in Lhadrung. The only one still alive. A man who supervised the burning of another fifteen gompas. Two hundred monks died inside as the buildings burned," Shan reported with a chill. He tore the entry he had transcribed from his notebook and dropped it onto the table in front of Tan. "It's your name."

Chapter Fourteen

Outside, Sergeant Feng stood uneasily between two knobs.

"Comrade Shan!" Li Aidang called from a dark gray sedan parked across from the restaurant. The assistant prosecutor opened the door and gestured for Shan to climb inside. "I thought we might chat. You know. Colleagues on the same case."

"So you returned safely. Kham is such an unpredictable place," Shan said dryly. He hesitated, seeing the uncertainty in Feng's eyes, then slid into the back seat beside Li.

"We found him, you know," Li announced.

Shan willed himself not to take the bait.

"That is to say, we persuaded a clan in the valley to tell us where his camp was."

"Persuaded?"

"Doesn't take much," the assistant prosecutor said smugly. "A helicopter, a uniform. Some of the old ones just whimpered. We found out where to look, but when we arrived they had gone. Fire ashes still warm. Not a trace." Li studied Shan. "As if they had been warned."

Shan shrugged. "Something I've noticed about nomads. They tend to move about."

The door was slammed shut by one of the knobs, who climbed behind the wheel and started the engine. As they drove away Shan turned to see the remaining soldier step in front of the driver's door of their own truck, blocking Sergeant Feng's way.

A shadowy figure in the front seat turned and looked at Shan without speaking.

"You remember the major," Li said.

"Major Yang, I believe," Shan observed. "Minder of Public Security."

"Exactly," Li confirmed tersely.

One side of the officer's face curled up in acknowledgment of Shan, then he turned away.

They moved out of town quickly, the horn blaring intermittently to scatter pedestrians and any vehicles that dared to get close.

Ten minutes later they entered an evergreen forest, in a small valley three miles from the main road. As they passed through the ruins of an ancient mani shrine wall, the trees began to assume an orderly appearance. They had been groomed. Spring flowers bloomed along the road, beside raked gravel.

They passed another wall, taller than the first, and entered the courtyard of a very old gompa. It had one tower of stone and gray brick and a small chorten, twice the height of a man, on the opposite side of the courtyard. Newly laid flagstone lined the courtyard. The walls had been replastered and were being painted. Along the far wall was a collection of statues of Buddha and other religious figures, several plated with gold. They were in a disorganized row, some facing the wall, some listing sharply, some propped against each other. Shan had the sense of visiting a wealthy, neglected villa. A faint aroma of peonies wafted through the courtyard as they climbed out of the car.

The major disappeared behind a large gate. Li led Shan into the anteroom of the assembly hall, switched on a lightbulb and gestured toward a rough wooden table surrounded by stools. Shan studied the wiring, which was new. Few of the remote gompas were wired for electricity.

Li made a gesture that swept the room. "We have done what we can to preserve it," he said with affected humility. "It is always a struggle, you know."

The floor was of the original wood planking, hand-cut centuries earlier. It was pockmarked with cigarette burns.

"There are no monks here."

"There will be." Li roamed about the room with the eye of an owner inspecting his premises. On pegs along the interior wall, robes had been arranged to give the effect of a lived-in gompa. "Director Wen is arranging everything. A stop for the Americans. A few reenactments. Let the Americans light some butter lamps and incense."

"Reenactments?"

"Ceremonies. For atmosphere." Li selected one of the robes, an antique ceremonial robe with gold brocade and silk panels depicting clouds and stars. He slipped off his suit jacket and with a grin tried on the robe, stroking the sleeves with satisfaction as he continued speaking. "We're finalizing things. Just a few more days before they arrive." He strolled the room like a proud cockbird, trying to catch a reflection of himself in the small window panes. "For a few dollars extra we'll let the Americans put on robes and spin prayer wheels. Soundtracks of mantras will play in the background. For a few more dollars we'll offer a one-hour course on how to meditate like a Buddhist."

"Sort of a Buddhist amusement park."

"Precisely! We think so much alike!" Li exclaimed, then sobered. "Which is why I had to speak to you, Comrade. I have a confession to make. I have not been totally open with you. But now I must be, to make you understand something. I have a concurrent investigation, separate from Prosecutor Jao's murder. More important. But what you are doing, you have no idea of how damaging it could be. You make it very difficult."

"Difficult?"

"Difficult for us to do the right thing. You are out of your element. You are being used."

"I'm confused," Shan said, studying a shelf of trinkets behind a table. "Exactly which right thing are you speaking of?" There were small ceramic figures of yaks and snow leopards, and an entire row of muscular Buddhas carrying Chinese flags.

Li moved to a stool beside Shan, oblivious to the sound of popping threads in the shoulders of the old robe as he sat. "Tan can pretend all he wants. It is a luxury of office. But you. You cannot pretend. I am sorry. We must be frank. You are a prisoner. You were a prisoner. You will be a prisoner. Neither you nor I can do anything to change that."

"Assistant Prosecutor Li. I lost the capacity to pretend many years ago."

Li laughed, and lit a cigarette. "Go back to the 404th," he said abruptly.

"It is not within my power."

"Join the strike. We can let you resolve it. Big hero. Notation in your file. Maybe save a lot of lives."

"What exactly are you offering?"

"We can reassign the troops."

"You're saying you will recall the knobs if I stop investigating?"

Li walked over to the shelf of ceramic novelties. He picked up one of the Buddhas and blew into the bottom. Smoke came out the eyes. "It would solve a lot of problems."

"You haven't said why."

"Obviously there are things I am not permitted to tell you."

"So you brought me here to tell me that you would not be telling me anything."

Li stepped back to his side and patted Shan on the back. "I like your sense of humor. I can tell you're from Beijing. Someday, who knows? You could fit well with us." He paced around Shan. "I brought you here to save you. The major and I are trying to find a way to be generous. There've been too many victims. There's no need for you to be hurt further. If Minister Qin in Beijing wants you in lao gai, that's between you and him. But Minister Qin is very old. Someday you may have another chance. I can see you are an intelligent man. A sensitive man. You will be of use to the people again one day. But not with Colonel Tan. He is very dangerous."

"I am no danger to him."

Li studied his cigarette. "I don't mean it that way. He manipulates you. He thinks he can ignore state procedures. Have you considered why he avoids the prosecutor's office?"

Shan did not answer.

"Or why he makes you work with unreliables?"

"Unreliables?"

"Discredited sources. Like Dr. Sung."

"I respect Dr. Sung's medical expertise."

Li shrugged. "Precisely my point. You weren't told about her problems. Her prejudices. Was refused her normal rotation home for neglect of duty."

"Neglect of duty?"

"Went off for a week on her own decision to work on unauthorized patients."

"Unauthorized patients?"

"A high mountain school. Very remote. Forgotten by anyone in Lhasa. Kids dying of something. They get things up there, diseases that have disappeared in the rest of the world."

"So the doctor was punished for helping children who were dying?"

"That's not the point. The stated procedure is for such parents to bring their children to the clinic. She left a number of important patients at the clinic. Some were Party members. She won't be going home. Not for a very long time."

"And no opportunity if she stays." Shan was tempted to ask when the doctor's indiscretion happened. She had been invited to dinner but later denied membership in the Bei Da Union. He remembered the nervous way she had recited to him party dogma on the inferiorities of the Tibetan minorities and policy on treating unproductive patients in the mountains. They had been words from a tamzing.

"You understand," Li said with affected gratitude. "You put me in a very awkward position, Comrade Shan. What you are saying is that you want me to trust you, aren't you?"

Shan did not reply.

"This is most unorthodox. The prosecutor's office confiding in a convicted criminal."

"I never had a trial, if that helps."

Li raised his brows and slowly nodded. "Yes, Comrade, good point. Not a convict, just a detainee." He lit a second cigarette from the butt of the first. "All right. You need to know. There is a corruption investigation. The biggest ever in Tibet. We were almost done. Jao was about to announce his conclusions. We can move soon. But you will make them flee."

"So Jao was killed by a suspect in his corruption investigation?" Shan asked. It would be a very balanced solution. The kind of ending that would please the Ministry of Justice.

"Not exactly. It's just that this hooligan monk Sungpo, he had no idea of the effects of his murder. With Jao gone, the corruption case is in ruins. We've had to piece it together. We owe it to Jao to finish. We owe it to the people. But you are stirring up too much dust. You are beginning to frighten our suspects. You will ruin it."

"If you're saying that Prosecutor Jao was going to arrest Colonel Tan, then Tan had more reason than anyone to kill Jao. Accuse him of the murder and Sungpo can be released. The knobs can stand down at the 404th. That's a solution."

"Give me some evidence."

"Against Colonel Tan?" Shan asked. "I thought you meant you already had evidence."

"One might surmise you could have reason to celebrate the passing of the old guard."

"I have a preference," Shan said contemplatively, "for natural causes."

"You can't possibly think he would protect you."

"I have been relieved of the need to worry about protection. I have been entrusted to the custody of the state."

A sneer built on Li's face. "You are his fallback. His safety net. If you fail to build a case, he will create one. He will have his own case file even if you do not finish yours. All your actions can be construed as an effort to protect the radicals. Obstruction of justice is a lao gai charge in itself. I told you. I made inquiries about you. You weren't picked by Tan simply because you were investigator. You were selected because by definition you are guilty. And expendable."

It was the only thing Li had said that Shan believed. Shan watched his own fingers move, seemingly of their own volition. They made a mudra. Diamond of the Mind.

"No one will defend you. No one will say Shan is a model prisoner, a worker hero. Tan can't even put your name on the report. You don't exist. There is no need for you to be a victim also."

It was the closest Li had come to putting his threat into words.

Shan studied his mudra. "This place," he said with sudden realization as he surveyed the room again. "It is the Bei Da Union."

Behind him, Shan sensed an abrupt movement by Li, as if his head had snapped up. "It is an old gompa. It has many uses."

"I saw a list of gompas licensed for reconstruction. This wasn't on it."

"Comrade. I fear for you. You don't want to listen to those who want to help you."

"Does it have a license?"

Li sighed as he eased off the ceremonial robe and tossed it on a stool. "It has been classified as an exhibition facility by Religious Affairs. It does not need a license."

Shan raised his palms in a gesture of frustration. "I admire your ability to reconcile it all. For me, it is so confusing. If a group paid by Beijing meets to discuss educating the people it is socialism at work. But if people wearing red robes do so it is an unlicensed cultural activity."

Li was studying Shan closely now. They were both aware of how dangerous the game was becoming. "You have been out of touch, Comrade. Much progress has been made in defining the socialist discipline for ethnic relations."

"I do not have the benefit of your training," Shan admitted. He rose and moved to the door.

"Where are you going?" Li asked, annoyed.

"The sun is coming through the clouds." Before Li could protest Shan was moving into the courtyard.

A van had arrived with markings for the Bureau of Religious Affairs. Workers were arranging benches at the side of the courtyard, as if for a lecture. Directing them was the young woman Shan had met at Director Wen's office– Miss Taring, the archivist.

The moment he saw her Shan understood. In their underground refuge the purbas had said they knew about Shan's discussion of the costume with Director Wen. There was only one person who could have told them. Miss Taring had told the purbas, or perhaps she was a purba herself. He studied her as though for the first time. Her hair was tied in a tight bun at the back, and she wore a white blouse with a long dark skirt that gave her the gleam of professionalism, the model worker. She stopped, nodded casually and started to turn, too, when she caught his gaze. She slowly turned away to issue orders to the workers, her hands behind her back. Shan was about to turn when he saw her fingers moving. Her knuckles clenched together in fists, the thumbs facing each other at forty-five degree angles, the hands almost touching. He had seen it before, an offering mudra. Aloke, the lamps to light the world.

She held the mudra only a moment, then slowly turned her head toward the rear of the courtyard. She then walked to the far wall and stood beside one of the large Buddha heads, turning at an angle toward something Shan could not see.