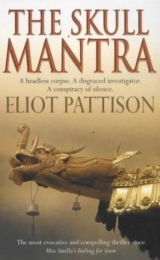

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"The investigation will be in my name. You're not just a trusty now," Tan said slowly, distracted by something ahead. "In fact, no one is to know. You will be my-" he searched for a word "– my case handler. My operative."

Shan took a step back, confused. Had Tan actually brought him to the cave simply to taunt him? "I can rewrite the report. I spoke to Dr. Sung. But the 404th is the problem. I can be better used there."

Tan held up his hand preemptively. "I have thought about it. You already have a truck. I can trust my old comrade Sergeant Feng to watch you. You can even keep your tamed Tibetan. An empty barracks at Jade Spring is being readied where you will sleep and work."

"You are giving me freedom of movement?"

Tan continued to survey the skulls. "You will not flee." When he turned to Shan there was a cruel flash in his eyes. "Do you know why you will not flee? I have had the benefit of Warden Zhong's advice." He turned to Shan with a sour, impatient countenance. "There is still snow in the highest passes. Soft snow, melting fast. Threat of avalanche. If you run, or if you fail to produce my report on time, I will assign a squad from the 404th. Your squad. No rotation. On the cliffs above the roads, testing for collapse. The 404th still has some of the old lamas arrested in '60. Some of the originals. I will order Zhong to start with them."

Shan stared at him in horror. Nothing about Tan made sense except his compulsion for terror. "You misunderstand them," he said in a near whisper. "My first day at the 404th, a monk was brought in from the stable. For making an illegal rosary. Two ribs cracked. Three fingers had been broken. You could still see the lines in his flesh where the pliers had gripped his knuckles. But he was serene. He never complained. I asked why he felt no rage. Do you know what he said? 'To be persecuted for traveling the correct path, to be able to prove your faith,' he said, 'is an event of fulfillment for the true believer.' "

"It is you who misunderstand," Tan snapped. "I know these people as well as you. We will never physically force them into submission. Otherwise my prisons would not be so full. No. You will do it, but not because they fear death," Tan said with bone-chilling assurance. "You will do it because you fear being responsible for their deaths."

Tan stepped another twenty feet down the tunnel to where the lanterns had stopped. The two guides wore wild, frightened expressions. One of them was shaking. As Shan stepped beside him, Tan grabbed the soldier's lamp and held it up to the third shelf. There, between two of the golden skulls, sat another head, a much more recent arrival. It still held its thick black hair and flesh and lower jaw. Its brown eyes were open. It seemed to be looking at them with a tired sneer.

"Comrade Shan," announced Tan, "meet Jao Xengding. The Prosecutor of Lhadrung County."

Chapter Four

The high-altitude sunlight exploded against his retinas as Shan left the cave. Stumbling forward, his hand covering his eyes, he heard rather than saw the argument. Someone was shouting at Tan with the unrestrained anger that could issue only from a Westerner. As he moved toward the sound Shan's vision cleared and he froze.

Tan had been ambushed. He had his back to a corner formed by the shed and one of the trucks. Like every other man in the compound, Tan seemed utterly paralyzed by the creature that had attacked him.

It was not just that his assailant was female, or even that she was speaking in English, but that she had porcelain skin, auburn hair, and stood taller than any of the Chinese in front of her. Tan looked up to the sky as though searching for the unlucky whirlwind that must have deposited her.

Shan, still numb from the discovery in the cave, took a step closer. The woman was wearing heavy hiking boots and American blue jeans. A small, expensive Japanese camera hung around her neck.

"I have a right to be furious," she shouted. "Where's the Religious Bureau? Where's your permit?"

Shan moved around the shed. A white four-wheel-drive truck was parked beside Tan's Red Flag limousine. He moved to the far side of the truck, where he was out of the colonel's sight but where he could still hear the woman plainly. He relished her words. In his Beijing incarnation he had read a Western newspaper once a week to maintain the language skills taught him in secret by his father. But it had been three years since he had heard or read an English word.

"The Commission was not notified!" she continued. "There is no Religious Bureau posting! I'm calling Wen Li! I'm calling Lhasa!" Her eyes flashed in anger. Even from twenty feet away Shan saw they were green.

Shan moved around the white truck. It was an American Jeep, a much newer version of the one Feng drove, fresh from the joint venture factory in Beijing. At the wheel was a nervous-looking Tibetan wearing spectacles with heavy black rims. On the driver's door was a symbol, a drawing of crossed American and Chinese flags, flanked top and bottom by the words Mine of the Sun, in Chinese and English.

"Ai yi, she's beautiful when she's angry," someone said over his shoulder. The words were spoken in perfect Mandarin but their rhythm was not Chinese.

Shan slipped to the side to get a look at the man. He was a lean, tall Westerner with long, straw-colored hair tied in a short tail at the nape of his neck. He wore gold wire-rimmed spectacles and a blue nylon down vest with an emblem that matched that on the truck. Throwing an amused sidelong glance at Shan, he turned back toward the woman, pulling an odd rectangular object from his pocket and raising it to his mouth. It was a mouth organ, Shan suddenly realized as the American began to play a song.

He played quite well, but loudly. Deliberately loudly. Many traditional American songs were popular in China, and Shan recognized his tune instantly. "Home on the Range."

Several of the soldiers laughed. The American woman cast a peeved glance at her companion. But Tan was not amused. As the woman raised her camera and aimed it at the cave, Tan snapped from his spell. He muttered a command and one of his men leapt forward to cover the lens with his hand. The American with the mouth organ kept playing, but his eyes hardened. He took several steps toward the woman, as though she might need his protection. Shan watched as two of Tan's officers quietly adjusted their position, so they remained between the American and the cave.

"Miss Fowler," Tan said in Mandarin, back in control, "defense installations of the People's Liberation Army are strictly classified. You have no right to be here. I could order your detainment." It was the most credible of bluffs. Tibet housed more of China's nuclear arsenal than any other region of the country.

The woman stared silently, defiance still in her eyes. The American man lowered the mouth organ and replied in English, though he had obviously understood Tan. "Great," he said, extending his wrists, "arrest us. That will guarantee the attention of the United Nations."

Colonel Tan threw a petulant glance at the American man, bent to the ear of one his aides, then offered a hollow smile to the woman. "This is no way for friends to behave. It's Rebecca, isn't it? Please, Rebecca, understand the problem you are creating for yourself and your company."

Someone grabbed Shan by the arm and pulled him toward the truck where Yeshe and Feng still sat. "Colonel Tan says you must go. Now," the soldier insisted.

Shan let himself be led to the truck, but at the door pulled away to stare once more at the strange woman. She gave him a fleeting glance, then turned again and locked gazes with him as she realized perhaps that Shan was the only Chinese there without a uniform. Her green eyes had a wild, restless intelligence. A question appeared on her face. Before he could tell if it was directed toward him, he was pushed into the truck.

***

A file was already on his desk at the prison administration office. It had been delivered personally by Madame Ko, and was captioned "Known Hooligans/Lhadrung County." It was an old file, dog-eared from use, and was separated into four categories. Drug cultists was the first. It was a quaint notion, abandoned by the police in China's large cities years earlier, that drug use was driven by fanatic rituals. Youth gangs. The fifteen individuals listed were all over thirty years of age. Criminal recividists. The list included everyone in Lhadrung who had previously served time in a lao gai prison, nearly three hundred names. Cultural agitators. It was by far the longest list. For every name either a gompa or the label "unregistered" was listed. They were all monks. Many had been detained during the Thumb Riots five years earlier. A dozen of the unregistered monks had an added notation. Suspected purba. He puzzled over the label. A purba was a ceremonial dagger used in Tibetan rituals. He scanned to the end. No list for homicidal protector demons.

He picked up the phone. Madame Ko answered on the third ring. "Tell the colonel there will need to be more autopsy work."

"Autopsy?"

"He'll need to tell Dr. Sung at the clinic about it."

"Wish I had known," she sighed. "I just got back from there."

"You went to the clinic?"

"He had me make a delivery. I just walked over there. All wrapped up in newspaper and plastic bags. Said he wanted her cabbage to stay fresh."

Shan stared at the receiver. "Thank you, Madame Ko," he mumbled.

"You're welcome, Xiao Shan," she said brightly, and hung up.

Xiao Shan. The words brought a sudden loneliness. He had not heard them for years. It was what his grandmother called him, the old-style form of address for a younger person. Little Shan.

He found himself staring out into the central office at a worker sharpening pencils. He had forgotten about sharpening pencils and the thousand other tiny acts that made up a day on the outside. He clenched his jaw, fighting back the question that no prisoner in the gulag dared ask: Was he capable of ever having a life on the outside again? Not would he be released, for every prisoner had to believe he would someday be released, but who would he be when he was released? Everyone knew stories of former prisoners who never adjusted, who were too scared to leave their beds, or who stayed bent forever as if chained, like the horse, which, once hobbled, never tries to run again. Why were there never stories of prisoners who succeeded after release? Perhaps because it was so hard to understand what success was for a survivor of the gulag. Shan remembered Choje's last words to Lokesh, after thirty years of sharing a prison hut. "You must teach yourself to be you again," Choje had said, as Lokesh cried on his shoulder.

He opened his notepad. They were still there, on the last page. His father's name. His name. Without thinking he drew another character, a complex figure, beginning with a cross with small slashes in each quarter pointing to the center. Thrashed rice, these first lines meant. They connected to the pictograph of a living plant over an alchemist's stove. Together they meant life force. It had been one of his father's favorite ideograms. He had drawn it in the dust of the window the day they came to take away his books. Choje had taught him its counterpart in Tibetan characters. But Choje always referred to it differently: the Indomitable Power of Being.

There was a movement in front of the desk. He slammed the notebook shut, his hands reflexively covering it. It was only Feng, standing as Lieutenant Chang approached.

Chang pointed at Shan and laughed, then leaned toward Feng and spoke in a low voice. Shan stared past them out into the office, watching the monochromatic figures move through their paces.

Opening the pad again, he remembered Passage Twenty-one of the Tao Te Ching and wrote it at the end of his investigation notes. At the center is the life force, it said. At the center of the life force is truth.

He propped the pad upright in front of him, open to the verse, and studied it. Every case has its own life force, he had once told his own deputies, its essence, its ultimate motive. Find that life force and find the truth. At the center there was a murdered prosecutor. Shan tilted his head and stared intensely at the verse. Or perhaps at the center was the 404th and a Buddhist demon.

He became aware of a small noise in front of him. "What are you doing?" Yeshe asked with a self-conscious glance back at Sergeant Feng. "I've been standing here for five minutes." He was holding a plate with three large momo dumplings. Beyond him, the office outside was empty. It was dark.

The momos were the only food Shan had seen all day. He waited until Feng turned his back and stuffed two into his pocket, then gulped down the third. It was rich, with real meat inside, prepared by the guards' kitchen. In the prisoners' mess the momos were stuffed with coarse grain, with a heavy portion of barley chaff always mixed in. His first winter, after drought had shriveled the fields, the momos had been filled with the ground corncobs used to feed pigs. Over a dozen monks had died of dysentery and malnutrition. The Tibetans had a word for such deaths by starvation, which had claimed thousands in the days when almost the entire monastic population of Tibet had been imprisoned. Killed by the momo gun. After the drought the Tibetan Friends Association, a Buddhist charity, had won the right to provide meals twice a week to the prisoners. Warden Zhong had announced it as a gesture of conciliation, and done so so cheerfully that Shan was confident that the warden was pocketing the money that would have otherwise fed the prisoners.

"I have compiled notes of our interview with Dr. Sung," Yeshe said stiffly, and pushed two pages of typed text across the desk.

"That's all you have been doing?"

Yeshe shrugged. "They're still working on the supply records. They had trouble with the computers."

"The lost supplies you mentioned?"

Yeshe nodded.

Shan considered the notes and looked up absently. "What kind of lost supplies?"

"A truck of clothing. Another of food. Some construction materials. Probably just some bad paperwork. Somebody counted too many trucks when they left the depot in Lhasa."

Shan paused to make a note in his book.

"But it's nothing to do with this," Yeshe protested.

"Do you know that?" Shan asked. "Most of my career in Beijing I spent on corruption cases. When it involved the army, I always went to the central supply accounts first, because they were so reliable. When they counted trucks, or missiles, or beans, they didn't do it with one man. They assigned ten, each counting the same thing."

Yeshe shrugged. "Now they use computers. I came for my next assignment."

Shan considered Yeshe. He wasn't much older than his own son, and, like his son, was so smart, and so wasted. "We need to reconstruct Jao's activities. At least the last few hours."

"You mean talk to his family?"

"Didn't have any. What I mean is, we need to visit the Mongolian restaurant in town where he had dinner that night. His house. His office, if they let us."

Yeshe had his own notepad now. He feverishly took notes as Shan spoke, then spun about like a soldier on drill and departed.

Shan worked another hour, studying the lists of names, writing questions and possible answers in his pad, each seeming more elusive than the last. Where was Jao's car? Who wanted the prosecutor dead? Why, he considered with a shudder, did Choje seem so perfectly assured that the demon existed? How is it that the prosecutor of Lhadrung County had appeared to be a tourist? Because he was preparing to travel? No. Because he had American dollars in his pocket, and an American business card. What kind of rage did this killer possess, to carefully lure his victim so far just to decapitate him? Not an instantaneous animal rage. Or was it? Could it have been a meeting turned sour, escalating to a fight? Jao was knocked unconscious and in a panic his assailant picked up– what, a shovel?– to finish the job and destroy Jao's identity in a single grisly act. But to then carry the head five miles to the skull shrine? Wearing a costume? That was not animal rage. That was a zealot, someone who burned with a cause. But what cause? Political? Or was it passion? Or had it been an act of homage, to lay Prosecutor Jao in such a holy place? An act of rage. An act of homage. Shan threw his pencil down in frustration and moved to the door. "I have to go back. To my hut," he told Sergeant Feng.

"Like hell," Feng shot back.

"So you and I, Sergeant, we are going to spend the night here?"

"No one said anything. We don't go to Jade Spring until tomorrow."

"No one said anything because I am a prisoner who sleeps in his hut and you are a guard who sleeps in his barracks."

Feng shifted uneasily from foot to foot. His round face seemed to squeeze together as he gazed toward the row of windows on the far wall, as though hoping to catch an officer walking by.

"I can sleep here, on the floor," Shan said. "But you. Are you going to stay awake all night? That's what you would need orders for. Without orders the routine must stand."

Shan produced one of the momos he had saved and extended it to Feng.

"You can't bribe me with food," the sergeant grunted, eyeing the momo with obvious interest.

"Not a bribe. We're a team. I want you in a good mood tomorrow. And well nourished. We're going for a ride in the mountains."

Feng accepted the dumpling and began to consume it in small, tentative nibbles.

Outside, the compound was gripped in a deathly silence. The crisp, chill air was still. The forlorn cry of a solitary nighthawk came from overhead.

They stopped at the gate, Feng still uncertain. From the rock face came the echo of a tiny ringing, a distant clinking of metal on metal. They listened for a moment and heard another sound; a low metallic rumbling. Feng recognized it first. He pushed Shan through the gate, locked it, and began running toward the barracks. The next stage of the 404th's punishment was about to begin.

***

Shan offered the remaining momo to Choje.

The lama smiled. "You are working harder than the rest of us. You need your food."

"I have no appetite."

"Twenty rosaries for lying," Choje said good-naturedly and laid the momo on the floor, between the altar marks. The khampa sprang forward, knelt, and touched his head to the floor. Choje seemed surprised. He nodded, and the khampa stuffed the dumpling into his mouth. He rose and bowed to Choje, then squatted by the door. The catlike khampa was the new watcher.

Suddenly Shan realized the other prisoners were not doing their rosaries. They were bent over their bunks, writing on the backs of tally sheets or in the margins of the rare newspapers that were sometimes brought by the Friends Association. A few wrote with the stubs of pencils. Most used pieces of charcoal.

"Rinpoche," Shan said. "They have arrived. By morning they will have taken over from the guards."

Choje nodded slowly. "These men– I am sorry, what is the word I hear for the Public Security troops?"

"Knobs."

Choje smiled with amusement. "These knobs," Choje continued, "they are not our problem. They are the problem of the warden."

"They have identified the dead man," Shan announced. Several of the priests looked up. He looked around as he spoke. "His name was Jao Xengding."

A sudden, silent chill fell over the hut.

Choje's hands made a mudra. It was an invocation of the Buddha of Compassion. "I fear for his soul."

From the shadows a voice called out. "Let him stay in hell."

Choje looked up in censure, then turned back with a sigh. "He will have a difficult passage."

Trinle suddenly spoke. "He will be in struggle for his deeds. And for the violence of his death. He could not have been prepared properly."

"He sent many to prison," Shan observed.

Trinle turned to Shan. "We have to get him off the mountain."

Shan opened his mouth to correct his friend, then realized he was not speaking of Jao's body.

"We will pray for him," Choje said. "Until his soul has passed we must pray."

Until his soul has passed, Shan reflected, he will continue to punish the 404th.

A monk brought one of the tally sheets for Choje to examine. He studied it, then spoke in low tones to the man, who took the scrap back to his bunk and began working on it again.

Choje looked at Shan. "What is it they are doing to you?" He spoke very quietly, so no one heard but Shan.

In that moment Shan saw Choje as in their first meeting: Shan kneeling in mud, Choje striding across the compound, oblivious to the guards, as serenely as if he were strolling across a meadow to retrieve an injured bird.

Shan had been in fragments when his jailers first released him into the 404th compound, shattered physically and mentally from three months of interrogation and twenty-four-hour political therapy. Public Security had intercepted him at the end of his last investigation, just as he was about to dispatch a very special report to the State Council instead of his official superior, the Minister of Economy. At first they had simply beaten him, until a Public Security doctor had expressed concern about brain damage. Then they used bamboo splints, but that had built such an inferno of pain he could not hear their questions. So they had progressed to subtler means, eventually shifting from hardware to chemicals, which were far worse because they made it so difficult to remember what he had already told them.

He had sat in his cell in Moslem China– once, in a room with a window, he had seen the endless expanse of desert that could only mean western China– and recited the Taoist verses of his youth to keep his mind alive. They had constantly reminded Shan of his crimes, sometimes reading like professors from blackboards in tamzing, or shouting from statements of witnesses he had never heard of. Treason. Corruption. Theft of state property, in the form of files he had borrowed. He had smiled dreamily, for they had never understood the nature of his guilt. He had been guilty of forgetting that certain anointed members of the government were incapable of crime. He had been guilty of mistrusting the Party, because he had refused to reveal all his evidence– not only to protect those who had given it to him but also, and this shamed him, to protect himself, for his life would be worthless once they thought they had everything. In the end, the only lesson of those months of endless, shredding pain, the one resolute truth Shan had learned about himself, and the great handicap that kept the pain alive, was that he was incapable of giving up.

Perhaps that was what Choje had seen that first hour when Shan had stumbled from a Public Security van into the compound, dazed, wondering if they had decided to risk shooting him after all.

The prisoners had at first seemed just as dazed, staring at him as if he were a dangerous new species. Then they seemed to decide he was just another Chinese. The khampas spat on him. The others mostly shunned him, some making a mudra of cleansing as though to spurn the new devil in their midst.

Shan had stood unsteadily in the center of the compound, knees shaking, considering what sort of new hell his handlers had found for him, when one of the guards shoved him. He fell into a cold puddle face first, and splattered mud on the guard's boots. As Shan struggled to his knees, the furious guard ordered Shan to lick his boots clean.

"Without a people's army the people have nothing," Shan had said with a doleful smile. A direct quote from the Inestimable Chairman, from the little red book itself.

The guard had knocked Shan back into the mud and was slamming Shan's shoulders with his baton when one of the older Tibetan prisoners walked toward them. "This man is too weak," the prisoner had said quietly. When the guard laughed the prisoner bent over Shan's prostrate body and took the blows on his own back. The guard administered the punishment intended for Shan with great relish, then called for help to drag the unconscious man to the stable.

The moment had changed everything. In one blinding instant Shan forgot his pain, even forgot his past, as he realized he had entered a remarkable new world, and that world was Tibet. A tall monk who introduced himself as Trinle helped Shan to his feet and led him into the hut. There had been no more spitting, no more angry mudras cast against him. Only eight days later, when the stable released Choje, did Shan meet him. "The soup," Choje had said with a crooked smile on seeing Shan, referring to the 404th's thin barley gruel, "always tastes better after a week away."

Shan looked up as he heard Choje's question again.

"What is it they are doing to you?"

He knew Choje did not expect an answer. It was simply the question he wanted to leave with Shan. The 404th would never be the same after the knobs took over. With a sudden aching in his heart, he realized Choje would probably be taken from them. He stared at a new mudra formed by the lama's hands. It was the sign of the mandala, the circle of life.

"Rinpoche. This demon called Tamdin-"

"It is a wonderful thing, is it not?"

"Wonderful?"

"That the guardian would appear now."

Shan wrinkled his brow in confusion.

"Nothing that happens in life is random," Choje explained.

True, Shan thought bitterly. Jao was killed for a reason. The killer wanted to be perceived as a Buddhist demon, for a reason. The knobs were there, prepared to destroy the 404th, for a reason. But Shan understood none of it. "Rinpoche, how would I recognize Tamdin if I find him?"

"He has many shapes, many sizes," Choje replied. "Hayagriva, they call him in Nepal and the south. In the older gompas they call him the Red Tiger Devil. Or the horse-head demon. He wears a rosary of skulls around his neck. He has yellow hair. His skin is red. His head is huge. Four fangs come from his mouth. On top is another head, much smaller, a horse's head, sometimes painted green. He is fat with the weight of the world. His belly hangs down. I have seen him in the festival dances many years ago." The mudra collapsed as Choje clasped his hands together. "But Tamdin will not be found unless he desires it. He will not be controlled unless he is empowered."

Shan considered the words in silence. "He carries weapons?"

"If he needs it, it will be in his hand," Choje said engimatically. "Speak to one of the Black Hat sect. There was once an old Black Hat ngagspa in the town. A sorcerer. Khorda, he was called. Practiced the old rites. Frightened the young monks with his spells. From a Nyingmapa gompa."

The Black Hats comprised the most traditional of the Tibetan Buddhist sects, of which the Nyingmapa was the oldest line, the one most closely linked to the shamans who once ruled Tibet.

"He could no longer be alive," Choje said. "When I was a boy he was already old. But he had apprentices. Ask who does Black Hat charms, who studied with Khorda."

Choje stared deeply at Shan, the way a father might contemplate a son departing on a long and dangerous journey. He gestured with his fingers. "Come closer."

As Shan moved within his reach Choje placed a hand on the back of Shan's head and pushed it down. He whispered to Trinle, who handed him a pair of rusty scissors, then snipped a lock of Shan's inch-long hair from just above his neck. It was what they did in initiation rites, for students being admitted to monasteries, to remind them of how Buddha had sacrificed to attain virtue.

The action, inexplicably, made Shan's heart race. "I am not worthy," Shan said as he looked up.

"Of course you are. You are part of us."

A deep sadness welled up within him. "What is happening, Rinpoche?"

But Choje only sighed, suddenly looking very tired. The old lama rose and moved to his bunk. As he did so, Trinle handed Shan a stained piece of paper on which an ideogram had been inscribed. "This is for you," Trinle said.

Shan futilely studied the paper. The characters were in the old style, like those on the medallion. Drawn on it was a series of concentric circles, encompassing a central lotus flower, each petal bearing secret symbols. "Is it a prayer?"

"Yes. No. Not exactly. A charm. A protector. Blessed by Rinpoche. Written on a fragment of an old holy book. Very powerful." Trinle grasped the lower corners. "Here," he explained, "you must fold it and roll it into a small roll. Wear it around your neck. We should find an amulet for it, on a chain. But there are none."

"Everyone is writing protection charms?"

"Not like this. Not so powerful. There was only this one fragment. And the invocation of the symbols. These are not words made by the hands or the lips. They are never spoken. Rinpoche had to reach up and capture them. It takes several hours to empower it. He worked all day. It has exhausted him. It is one that will be recognized by Tamdin, one that can be detected from this demon's world, so he knows you are coming. It is not simply protection. It is more like an introduction, so you can commune with him. Choje says you are walking the path of protector demons."

Meaning they are about to attack me, Shan was tempted to ask, when another question occured to him. How had Choje obtained a fragment of an ancient manuscript?

Some monks placed their charms on the altar, looking expectantly toward Choje. Others carried theirs to a bunk at the rear. Shan stepped toward it. One of the old monks sat in the bed with a strange patchwork of charms. He was joining the tally sheets into a larger charm, deftly tying them together with tiny braids of human hair.

Shan realized Trinle was staring at the thick pad of paper in his pocket. He ripped off a dozen blank pages and handed them to Trinle, with his pencil.

"The others. What are the other charms?"

"Each of us does what he can. Some are trying to prepare Bardo rites for the jungpo. Others are just protection charms. I do not know if Rinpoche will bless them. Without the blessing from one of power, they will be useless."