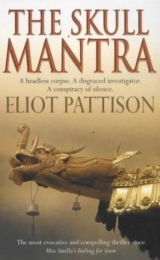

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"But you heard them," Yeshe protested. "There're only half a dozen."

"The shoes," Shan said. "I couldn't understand why Balti had two left shoes under his bed."

***

Three hours later, as they approached the battered buildings that comprised the collective, Sergeant Feng slammed on the brakes and pointed. A helicopter bearing the insignia of the border commandos sat at its perimeter, guarded by a soldier with an automatic rifle.

"Congratulations," Feng muttered. "Your guess has been confirmed."

Yeshe started to speak, but his words were lost in a sharp intake of breath. Shan followed Yeshe's gaze. Li Aidang was standing in the center of the compound, arms akimbo, with the air of a military commander. Behind him, in the pilot's seat of the helicopter, Shan saw a familiar face in sunglasses. The major. He suddenly realized that for all his bravado Li, like so many others, might only be another pawn.

The assistant prosecutor greeted Shan with a condescending smile. "If he's alive I'll have him in an interrogation cell by noon tomorrow," he vowed smugly. Without waiting for a question, he explained. "It's simple, really. I realized a security check would have been necessary for the chauffeur of an important official. Public Security computers had all the records of his past life."

Shan had once participated in an audit of the billions spent by Beijing on central computers. Priority had gone to the Public Security applications. The 300 Million Project, they had called it. Shan had thought at first that it described the funding for the project, but in fact it was the number of citizens who had at one time fallen under scrutiny by the Bureau. He had begun to convince himself that it was a welcome efficiency. Until he discovered his own name on the list.

"So he is here?"

"This is his family's collective. Though no one has seen him for a year, maybe two."

"His family?"

"They're on the high plateau," Li said, pointing to the north. "Chasing yak and sheep."

"Then he can be brought back here," Shan suggested. "Send someone from the collective who knows him."

"Impossible," Li shot back. "He must be placed in our custody. He will be arrested and removed to Lhadrung."

"There is no evidence against him, only conjecture."

"No evidence? You saw what was in his tenement. Clear links to hooliganism."

"A little Buddha and a plastic rosary?"

"He fled. You forgot he fled."

"Why are you so sure that he's here? I thought you said he ran with the limousine to Sichuan. A limousine does him no good in Kham."

"Strange question."

"What do you mean?" Shan asked.

"Here you are, searching for him."

Shan stared at the helicopter. "If you go to arrest him he will bury himself in the mountains."

"You forget that I know Balti. He will react better to a familiar face."

Shan considered the assistant prosecutor. Balti, he knew, might not survive an arrest by Li and the major. Khampas seldom submitted peacefully. And if Balti died, Shan could never forgive himself, for somehow he knew that Li was only interested in Balti because of Shan's own interest. But who had told him?

With a chill he looked back and saw Yeshe speaking with the major beside the helicopter. The major became animated, almost violent, shaking a piece of paper at Yeshe, who looked as though he were about to cry. Then the major pointed a finger at Yeshe's chest. Yeshe recoiled, as if struck. Ripping the paper in half, the major spat a final curse and climbed back into the machine. Li, also watching now, uttered a disappointed sigh.

"Balti's interrogation will be completed by the time you return," Li declared icily. "We will take careful notes for your review." He darted to the machine and climbed aboard.

They watched in silence as the helicopter disappeared over the mountains. "You have destroyed him," Yeshe accused.

"I wasn't the one who invited them," Shan said bitterly.

"It wasn't me," Yeshe said very quietly, still watching the horizon. "The old woman at his loft, she expects me to help Balti."

Shan wasn't sure he heard correctly. He was about to ask, when Yeshe turned to him with great pain in his eyes. "He offered me a job," Yeshe said in a hollow voice. "Just now. The major had work papers filled out in my name, for a real job, as a clerk with the Public Security Bureau in Lhasa, maybe even Sichuan. The signatures were already on them."

"You turned it down?"

Yeshe looked at the ground, the torment still on his face. "I told him I was busy right now."

"Shit, you said!" Feng gasped.

"He said it was now or forget it. He said maybe I could bring your case notes. I told him I was busy." He searched Shan's eyes for something, but Shan did not know what to offer. Confirmation? Sympathy? Fear?

"Sometimes," Yeshe continued, "these past few days, I think maybe it is true, what you said. That innocent people will die if we don't do something."

There was something unfamiliar in Sergeant Feng's eyes now as he gazed at Yeshe. For a moment Shan thought it might be pride. "I knew that boy Balti," Feng said suddenly. "He never hurt anybody."

Shan realized that both men were looking at him expectantly. "Then we have to find him before they do," he said, and opened the back of the truck to search through a pile of rags. He produced a tattered shirt and measured it against Feng's shoulders.

***

It was evening by the time they had climbed the long, increasingly high ridges that formed a fifty-mile stairway onto the high plateau, and located one of the nomad camps. They had sighted the three tents miles away as they drove onto the plateau, but had dismissed the low, gray shapes as rock outcroppings until they saw the long line of goats tied to a central tether nearby, their horns interlocked to keep them stable for milking. The squat, yak-hair tents were tied to the ground with stakes and leather straps, heightening the impression of crevassed boulders worn down by centuries of wind.

They stopped the truck fifty yards from the camp, and moments later were walking toward the tents, Sergeant Feng's uniform and gunbelt covered by the long shirt.

There were no humans to be seen. Prayer flags fluttered beyond the tents. Butter churns stood idle. Dried dung had been piled near the tents. Beyond the camp stood a small herd of yak, grazing on the spring grass. A goat with a ribbon tied on its ear grazed without fetters. It had been ransomed. By the entry to the largest tent the skull of a sheep hung over a willow rod frame in which yarn had been interwoven in geometric patterns. Shan had seen khampas make the same patterns with blanket thread at the 404th. It was a spirit trap.

A dog barked from the line of goats. A puppy on a tether lurched forward, upsetting a butter churn. From a bundle of fleece by the first tent a baby cried, and immediately the tent disgorged its inhabitants. Two men appeared first, one wearing a fleece vest, the other a heavy chuba, the thick sheepskin overcoat favored by many Tibetan nomads. Behind them Shan could see several women clad in patchwork tunics; soot and grime muted the once vibrant colors of their clothing. A child, a boy of no more than three, wandered out, his chin and lips covered with yogurt.

The man in the vest, his leathery face lined with wrinkles, gave them a sour acknowledgment, then disappeared into the tent and emerged with a soiled envelope stuffed with papers. He extended it toward Shan.

"We are not birth inspectors," Shan said, embarrassed.

"You are buying wool? It is too late. Last month was wool." The man was missing half his teeth. With one hand he tightly gripped a silver gau which hung from his neck.

"We are not here for wool."

From his jacket pocket Feng produced a piece of candy wrapped in cellophane and extended it toward the child. The boy approached cautiously, grabbed the candy and ran back to stand between the two men. The man in the chuba pulled the candy from the boy and smelled it, held it to his tongue, then returned it to the boy. The boy uttered a squeal of delight and ran inside. The man nodded, as though in gratitude, but the suspicion on his face did not disappear. He stepped aside and gestured for them to enter the tent.

It was surprisingly warm inside. Panels of yak-hair cloth, the same used for the tent itself, hung along one side to create a private dressing chamber. An ancient rug, once red and yellow but reduced to shades of soiled brown, served as the floor, bed, and chair for the tent's inhabitants. A three-legged iron brazier sat near the center, holding a huge kettle over smoldering embers of a wood fire. A small wooden table made with pegs and hinges for disassembly when moving camp held two incense burners and a small bell. Their altar.

Ten khampas were huddled, wary as deer, on the far side of the altar, as though it might protect them. The six women and four men, appearing to span four generations, were dressed in thick, dirty woolen skirts and aprons of faded red and brown stripes and heavy chubas that looked to have weathered many years of storms. A child of perhaps six wandered out of the group, clad in a length of yak felt draped around his body and tied at the waist with twine; a woman pulled the child into her skirt with a desperate look toward Shan. Necklaces of small silver coins, interspersed with red and blue beads, were the only adornment on the women. All their faces, male and female, were round, their cheekbones high, their eyes intelligent and scared, their skin smudged with smoke, their hands thick with calluses. One frail gray-haired woman leaned against a tent pole near the rear.

There was dead silence as everyone stared across the smokey chamber. The man in the vest, now holding the baby, still in its fleece cocoon, entered and uttered a single syllable. The knot of khampas slowly dispersed, the men sitting around the brazier, the women moving toward three heavy logs that held cooking utensils. The man, apparently a clan leader, gestured for his visitors to sit on the carpet.

The women chipped pieces from a large brick of black tea and dropped them into the kettle. Uncertain what to say, but compelled by their tradition of hospitality, the men talked of their herds. A ewe had birthed triplets. The poppies had been thick on the southern slopes, one of them said, which meant that this year's calves would be strong. Another asked if the visitors had any salt.

"I am looking for the Dronma clan," Shan said as he accepted a bowl of buttered tea. On the table he noticed a framed photograph, face down, as though dropped in haste. As he leaned toward the table he noticed that the hanging panels at the back of the tent were moving.

"There are many clans in the mountains," the old man said. He called for more tea, as though to distract Shan.

Shan picked up the photo. One of the women spoke urgently in the khampa dialect, and the younger men seemed to tense. The photo was sticking an inch out of the frame. It was Chairman Mao. Underneath he could see another image, the beads of a rosary and a red robe visible beneath Mao. It was a common practice in Tibet to keep a photo of the Dalai Lama in a conspicuous spot to bless the home, to be quickly covered by one of Mao when government callers arrived. Years earlier, mere possession of an image of the Dalai Lama had guaranteed imprisonment. As the woman noisily served tea to Feng, Shan pushed down the photo of Mao to finish covering the secret image, then stood it up on the table, facing away from them.

He sat on the rug, conspicuously crossing his legs under him in the lotus fashion favored by the Tibetans. During the Demolish the Four Olds campaign Tibetans had been ordered not to sit cross-legged. "This clan has a son named Balti," Shan continued. "He worked in Lhadrung."

"Families stay together here," the herder observed. "We don't know much about the other clans." The khampas looked down fretfully, watching the coals. Shan recognized the nervousness. No Chinese came who was not a wool buyer or a birth inspector. Shan drained his bowl and stood, surveying the khampas, none of whom would look at him. He stepped toward the hanging panel and pulled it aside.

Two young women were sitting behind it. They were pregnant.

"They are not inspectors," said one of the girls as she boldly pushed past him. She couldn't have been more than eighteen. "Not with a priest," she said with a defiant smile toward Yeshe. She helped herself to some of the tea. "I know the Dronma clan."

One of the older women snapped out a complaint.

The girl ignored her. "Doesn't matter. No one could tell where to find them. Too few for a full camp. All they can do is work the herder tents, in the high valleys."

"Where?"

"Say a prayer for my baby," she said to Yeshe, patting her stomach. "My last baby died. Say a prayer."

Yeshe looked at Shan uncomfortably. "I am not qualified."

"You have a priest's eyes. You are from a gompa, I can tell."

"A long time ago."

"Then you can say a prayer. My name is Pemu." She cast a defiant glance around the chamber. "They want me to say Pemee, to make it sound Chinese. Because of the Four Olds campaign. But I am Pemu." As if to punctuate her statement she pulled a pin from her hair, releasing a long braid into which turquoise beads had been woven. "I need a prayer. Please."

Yeshe cast an awkward glance at Shan, then moved outside, as though to flee. The girl followed him. One of the women threw open the flap to watch. The girl called to Yeshe without response, then ran past him and knelt in front of him. As he tried to sidestep her, she grabbed his hand and put it on her head. The action seemed to paralyze him. Then slowly he withdrew the rosary from his pocket and began speaking to the girl.

The action pierced the tension in the tent. The clan began preparing dinner. One of the women began to mix tsampa with tea to make pak, a khampa staple. A pot was put on the fire with mutton stew. A woman pulled blackened loaves from the ashes. "Three strikes bread," she explained as she handed a piece to Shan. "One, two, three," she counted as she struck the loaf against a rock. On the third strike the outer shell of ashes and carbon fell away, revealing a golden crust. Shan was offered the first slice. He broke it in half and with a bow of his head solemnly placed one piece on the makeshift altar.

The herder in the vest cocked his head in curiosity at Shan. "The Dronma," he said, "they follow the sheep. In the spring the yaks come down from the high land where they wintered. The sheep go up. Look for small tents. Look for prayer flags." He drew a map of likely locations, seven in all, in Shan's pad.

As he did so Shan became aware of a new sound, from another tent. It was one of the rituals he had learned at the 404th. Although the roads were already muddy, someone was praying fervently for rain.

Feng brought blankets from the truck and the three men slept with the children, rising when the goats began to bleat for the dawn milking. Shan folded one of the blankets and left it as a gift at the entrance of the camp.

Inside the truck, sleeping on the back seat, was Pemu.

"I will go with you," she said, rubbing his eyes. "My mother was Dronma clan. I will go and see my cousins." She made room for Shan and offered him a piece of bread.

The distances were not that great. She did not need their truck to see her cousins. Perhaps, Shan considered, it was a test, a challenge. A Public Security squad would never accept a passenger.

They had covered three of the valleys by midmorning and scanned the slopes with binoculars, to no avail. The skies began to darken. The herders had prayed for rain. Suddenly he understood why.

"Yesterday," he said to the girl, who watched intently out the window, "your people saw a helicopter didn't they?"

"The helicopter is always bad," she said, as if there was but one in existence. "When I was young the helicopter came."

Shan looked at her expectantly.

Pemu chewed her lip. "It was a very bad day. At first we thought the Chinese had a new machine to make thunder. But it wasn't thunder. They came to earth by the camp. I was only four." She looked out the window again. "It was a very bad day," she repeated with a distant, vacant stare.

Pemu moved to the edge of the seat as they approached an outcropping along the path. When the track moved into a small, rugged canyon she asked to get out. "To clear rocks," she said. "I will walk in front."

But Shan saw no rocks. Feng's hand instinctively moved to his pistol, and suddenly Shan realized that she had come to protect them, to use herself as a shield. After a moment, Feng, too, seemed to understand. His hand moved away from his holster, and he concentrated on keeping the vehicle as close to the girl as possible. They moved slowly, in brittle silence.

Shan thought he saw a glimmer of metal ahead. The girl began singing, loudly. The glimmer was gone. It could have been a gun. It could have been a particle of crystal catching the sun.

As they left the canyon she returned to the truck, with a new, haggard look. She began rubbing her belly. She started singing again, to her baby now.

"My uncle is in India," she said suddenly. "In Dharamsala, with the Dalai Lama. He writes me letters. He says the Dalai Lama tells us to follow the ways of peace."

They almost missed the small black tent in the fifth valley, in the shelter of a ledge. It took nearly an hour for Pemu to lead Shan and Yeshe up the steep switchbacks that led to the camp. Three sheep were tethered to a stake near the tent. Red ribbons were tied to their ears. A huge long-haired dog, a herder's mastiff, sat across the entrance to the tent. It reacted only with its eyes, watching them intently, then bared its teeth when they reached the smoldering campfire.

"Aro! Aro!" Pemu called out, taking a tentative step toward the hearth.

"Who would it be then?" a ragged voice called from inside. A small swarthy face appeared just above the dog. "You're right, Pok," the man said to the animal. "They don't look so fearsome." He laughed and disappeared for a moment.

He came out on a crutch. His left leg was gone below the knee. "Pemu?" he said, squinting at the girl. "Is it you, cousin?" He seemed choked with emotion.

The girl produced a loaf of bread from a bag around her waist and handed it to him. "This is Harkog," she said, introducing him to Shan. "Harkog and Pok are responsible for this range. We're not sure which is in charge."

Harkog's mouth opened in a crooked smile that showed only three teeth. "Sugar?" he asked Shan abruptly. "Got sugar?"

Shan explored the bag Yeshe had brought from the truck and found an apple, brown with age. The man accepted it with a frown, then brightened for a moment. "Tourists? Big power place on the mountain. I can take you. Secret trail. Go there, say prayers. When you go home you will make babies. Always works. Ask Pemu," he added with a hoarse laugh.

"We're looking for your brother. We want to help him."

The man's carefree expression disappeared. "Got no brother. My brother's gone from this world. Too late to help Balti."

Shan's heart sank. "Balti has died?"

"No more Balti," Harkog said, and began tapping his forehead with his fist, as if in pain.

Pemu pulled the tent flap open. Inside there was a vague human shape, a shell of a man with a gaunt face and eyeslike the sockets of a skull. "Just his body is here," Harkog said. "Not much left. For days now. He stays awake. Night and day, with his mantras." He studied the rosary hanging from Yeshe's belt. "Holy man?" he said with new interest.

Yeshe did not reply, but stepped closer to the tent. "Balti Dronma. We must speak with you."

The brother did not protest as Shan and Yeshe entered the tent and sat down.

Pemu stepped in behind them. "He's more dead than alive," she whispered in horror.

"We have questions," Shan said quietly. "About that night."

"No," Harkog protested. "He's with me. All those nights."

"What nights?" Shan asked.

"Whatever nights you ask about."

"No," Shan said patiently. "That last night in Lhadrung he was with Prosecutor Jao. When Jao was murdered."

"Don't know nothing about murder," Harkog muttered.

"The prosecutor. Jao. He was murdered."

Harkog seemed not to hear. He was staring at his brother. "He ran. He ran and ran. Like a jackal he ran. For days he ran. Then one morning I see an animal under a rock. Smells like a dying goat, the dog said. I reached under and pulled him out."

"We came from Lhadrung to understand what he saw that night."

"You do mantra," Harkog said suddenly to Yeshe. "Protect against demons while he sleep. Call back his soul so he can rest. Afterwards maybe he talk."

Yeshe did not reply, but awkwardly sat next to Balti.

Satisfied, Harkog left the tent.

"Like you blessed my baby," Pemu said to Yeshe.

Yeshe looked beseechingly to Shan. "I'm sorry," he said twice, once to Shan, and once to the woman. "I am not able to do this thing."

"I remember what the woman said at the garage," Shan reminded him. "Your powers aren't lost, they have only lost their focus."

Pemu pressed the back of his hand against her forehead.

Yeshe emitted a little groan. "Why?"

"Because he is dying."

"And I am supposed to work a miracle?"

"The medicine he needs can't be provided by a doctor," Shan said.

Pemu still held Yeshe's hand. He looked at her with a new serenity. Perhaps, Shan considered, a miracle was already underway.

Shan sat with the herdsman outside as Pemu stoked the fire and fixed tea. A clap of thunder shook the air about them. A curtain of rain pushed up the valley. As Harkog fixed a sheltering canvas over the fire circle, a chant began inside.

Shan listened to the drone of Yeshe's chant for an hour, then left to bring back Feng and the food in the truck. The sergeant paused as they were leaving the vehicle, and ran back. "Have to hide the truck," he said over his shoulder. He did not say from whom.

By the time they returned the rain had stopped and Yeshe was exactly as Shan had left him, seated in front of Balti's pallet, repeating his mantra of protection. There would be no stopping now until it was done. And no one, not even Yeshe, knew when that would be.

They gathered firewood and cooked a stew as the sun set, then ate in silence as the heavens cleared and Yeshe droned on inside the tent. Shan sat with Pemu and watched the new moon climb across the eastern sky. A solitary nighthawk called from the distance. Wisps of mist wandered down the slope. Feng lay down with a blanket and in a moment was snoring. Yeshe droned on. Pemu found a fleece and curled up in it, staring at the fire. At the edge of the flickering circle of light Harkog sat with Pok, the dog, facing the darkness. Yeshe was in his sixth hour of chanting.

Everything felt so distant to Shan. The evil that lurked in Lhadrung. The gulag he would return to. Even the ever-present tentacles of Minister Qin and Beijing seemed part of a different world for the moment.

From his bag Shan pulled the rice paper and ink stick he had purchased from the market. It had been a very long time. So many festivals had been missed. He rubbed the stick and with a few drops of water made ink in a curved piece of bark. He practiced, making small strokes in the air with the brush, composing the words in his mind before laying out the sheet and beginning to draw. He used the elegant old-style ideograms he had learned when he was a boy.

Dear father, he began, forgive me for not writing these many years. I embarked on a long journey since my last letter. Famine raged in my soul. Then I met a wise man who fed it. The strokes had to be bold yet fluid, or his father the scholar would be disappointed. Written properly, his father would say, a word should look like wind over bamboo. When I set out I was sad and afraid. Now I have no sadness left. And my only fear is of myself. He used to write letters often, alone in his tenement in Beijing. He read the ideograms over, unsatisfied. I sit on a nameless mountain, honored by mist and your memory, he added, and signed it as his father would call him. Xiao Shan.

Folding the second sheet into an envelope for the first, he pulled a smoldering stick from the fire and stepped into the darkness. He walked in the moonlight until he reached a small ledge that overlooked the valley, then made a small mound of dried grass between two stones and laid the letter on top. He studied the stars, bowed toward the mound and ignited it with the stick. As the ashes rose toward heaven, he watched reverently, hoping to see them cross the moon.

He lingered, covered in stars. He smelled ginger and listened to his father, certain now that he could remember joy.

Halfway back to the camp his heart leapt to his throat as a black creature appeared on the path in front of him. It was Pok. The huge dog sat and blocked his way.

"They say it was a riding accident but it wasn't," a voice rang out from the shadows beside the trail. It wasHarkog. He had a strange new determination in his voice. "It was a land mine. Running from the PLA. Suddenly I was in the air. Never heard the explosion. My leg flew past me while I was still in the air. But the soldiers stopped. The bastards stopped." He stepped from the shadows and looked up into the sky, just as Shan had been doing.

"You still stopped them?"

"Three of them came charging after me, to finish me. I shouted a curse and threw my leg at them. They fled like puppies."

"I am sorry about your leg."

"My fault. I should not have run."

They walked back together, slowly, silently, Pok leading the way.

"We could take you both back if you want," Shan offered.

"No," the man said in a slow, wise voice. "Just take his Chinese clothes. Everything else from Lhadrung. He must wear a fleece vest again. This has happened to him because he tried to be someone he is not. I got a truck ride there once. To Lhadrung. Good shoes. But that Jao, he was bad joss."

"You knew Jao?"

"I rode in the black car with Balti once. That Jao, he had the smell of death."

"You mean you knew Jao was going to die?"

"No. I mean people around him died. He had power, like a sorcerer. He knew powerful words that could be put on paper to kill people."

They were close enough to see the glow of the campfire when Pok growled. There was a shadow against the rock, waiting. Harkog muttered an order to the dog and the two had already moved on toward the camp before Shan recognized Sergeant Feng.

"I know what you were doing," Feng said. "Sending a message."

Shan clenched his jaw. "Just walking."

"My father tried to teach me when I was young," Feng said, in a voice that seemed to ache. Shan realized he had misread Feng. "To speak to my grandfather. But I lost it. Up here, so far away. It makes you think about things. Maybe-" He was struggling. "Maybe you could show me how again."

Trinle had once told Shan that people had day souls and night souls, and the most important task in life was to introduce your night soul to your day soul. Shan remembered the talk of Feng's father on the road to Sungpo's gompa. Feng was discovering his night soul.

They moved back to the ledge where Shan had sent his letter. Feng lit a small fire and produced a pencil stub and several of the blank tally sheets from the 404th. "I don't know what to say." His voice was very small. "We were never supposed to go back to family if they were bad elements. But sometimes I want to go back. It's more than thirty years."

"Who are you writing to?"

"My grandfather, like my father asked."

"What do you remember about him?"

"Not much. He was very strong and he laughed. He used to carry me on his back, on top of a load of wood."

"Then just say that."

Feng thought a long time, then slowly wrote on one of the sheets. "I don't know words," he apologized and handed it to Shan.

Grandfather, you are strong, it read. Carry me on your back.

"I think your words are very good," Shan said, and helped him fashion an envelope from the other sheets. "To send it you should be alone," he suggested. "I will wait down the trail."

"I don't know how to send it. I thought there were words."

"Just put him in your heart as you do it and the letter will reach him."

***

When they returned to camp, Harkog, Yeshe, and Balti were sitting at the fire. Pemu, speaking in the low comforting tones that might be used with an infant, was feeding Balti spoonfuls of stew. The gauntness seemed to have been lifted from Balti and transferred to Yeshe, who studied the flames with a drained, confused expression.

"We visited your house," Shan began. "The old woman married to the rat showed us the hiding place. It was made for a briefcase."

Balti gave no sign of having heard.

"What was in there that was so dangerous?"

"Big things. Like a bomb, Jao says." Balti's voice was thin and high-pitched.

"Did you ever see these things?"

"Sure. Files. Envelopes. Not real things. Papers."

Shan shut his eyes in frustration as he realized why Jao had trusted him with the papers. "You can't read, can you?"

"Road signs. They taught me road signs."

"That night," Shan said. "Where were you driving?"

"The airport. Gonggar. The airport for Lhasa. Mr. Jao trusts me. I'm a safe driver. Five years no accidents."

"But you took a detour. Before the airport."

"Sure. Supposed to go to airport. After dinner he told me different. All excited. Go to the South Claw bridge. The new one over the Dragon Throat built by Tan's engineers. Big meeting. Short meeting. Won't miss the plane, he said."

"Who did he meet?"

"Balti just the driver. Number one driver. That's all."

"Did he take his briefcase?"

Balti thought a moment. "No. In the back seat. I got out when he got out of the car. It was cold. I found a jacket in the back. Prosecutor Jao gives me clothes sometimes. We're same size."

"So what happened when Jao got out of the car?"

"Someone called out to him from the shadows. He walked away. So I sat and smoked. On the hood of the car I smoked. Half a pack almost. We're going to be late. I honk the horn. Then he comes out. He's plenty mad. He's going to eat me like a pack of wolves. I never meant it. Maybe it was the horn. He was plenty angry."