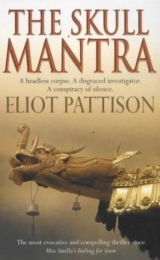

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

He entered along with a tour group, then moved in the cover of the crowds through the exhibits, willing himself not to linger at the exquisite displays of skull drums, ceremonial jade swords, altar statues, rich thangka paintings, crested hats, and prayer wheels. He paused only once, in front of a display of rare rosaries. There in the center was one of pink coral beads carved like tiny pinecones, with lapis marker beads. He stared at it sadly, then wrote down the collection inventory number and moved on.

Suddenly he was at the exhibit of costumes for demon protectors. There was Yama, the Lord of the Dead, Yamantaka, Slayer of Death, Mahakala, Supreme Protector of the Faith, Lhamo, Goddess Protector of Lhasa. And in the last case, Tamdin the Horse-headed.

The magnificent costume was there, its face a savage bulging mask of red lacquered wood, four fangs in its mouth, a ring of skulls at its neck, a tiny, ferocious, green horse head rising above its golden hair. Shan shivered as he studied it, his hand clamped on the gau around his neck that now contained the Tamdin summoning spell. The arms of the demon lay beside the mask, ending in two grotesque clawed hands, identical to the smashed one found at the American mine.

It was small comfort to confirm that the hand was indeed that of Tamdin, for the costume in the museum was intact, and in Lhasa, not in Lhadrung. There was a second costume but if it did not belong to the museum Shan had no way to trace it, no way to link it to Jao's killers.

He stared at the exhibit in deep thought, waited for the room to empty, and opened a door. A janitor's closet. He began to shut it, then paused and pulled out the broom and a bucket. He moved slowly through the building, sweeping as he watched the interior doors. Suddenly, and with a wrench of his gut, he saw someone new, a Chinese with bullet-hole eyes trying quite futilely to look interested in the exhibits. The man surveyed the room, not noticing Shan, then gave a snort of impatience and moved with a military gait into the adjoining hall. Shan stayed in the shadows and watched, to his horror, as the man conferred with two others, a young woman and a man dressed as tourists. They left the room at a trot and Shan stepped inside the first door that was not locked.

He was in a short corridor that opened into a large office chamber divided into cubicles. Most of the desks were empty. On a bench in the hall was a white technician's coat. Abandoning the bucket and broom, he put on the coat, then picked up a clipboard and pencil from the first desk.

"I lost my way," he said to the woman at the first occupied desk. "The inventory."

"Inventory?"

"Exhibits. Artifacts in storage."

"It's usually the same," she said in a superior tone.

"The same?"

"You know. Two of each piece. One on display, one in storage. In the basement. Parallel collection, the curator calls it. Makes cleaning and examination easier. One upstairs. One downstairs, arranged by their inventory number sequence."

"Of course," Shan said, with renewed hope. "I meant the organization charts. The location of artifacts."

"In notebooks. On the library table."

In the small library at the back of the corridor he found a thick black binder, its vinyl covers worn through to the cardboard at the edges. He had already located a section entitled Costumes when an older woman appeared at the door.

"What is it?" she snapped.

Shan started, then settled back into the chair before looking at her. "I'm from Beijing."

The announcement bought him another thirty seconds. He kept searching as the woman lingered at the doorway. Ceremonial headdresses. Demon dancer costumes.

"No one informed me," the woman said with a suspicious tone.

"Comrade, certainly you realize audits are not nearly so effective when advance warning is given," Shan said curtly.

"Audits?" She paused, then slowly entered and walked around the table.

As she saw Shan's clothing a sharp hiss of air escaped her lips. "We will need identification, Comrade."

Shan kept studying the books. "They said to leave it at the front desk. We have much work here." He gestured to a chair. "Perhaps you would like to help."

The woman spun about and disappeared down the hall. Tamdin, the book said, Code 4989. Set One from Shigatse gompa, 1959. Set Two from Saskya gompa, dated only fourteen months earlier. He walked quickly to the corridor and began checking the doors again. The third one opened onto descending stairs.

The basement shelves rose from the dirt floor to the ceiling, crammed with boxes of wood, wicker, and cardboard. They were arranged by inventory number as the girl had explained. He darted down the rows, desperately scanning the numbers at the end of each shelf. Suddenly there was a new sound, the unmistakable sound of running feet on the floor above.

He found the 3000 series, and kept running. Then the 4000. Shan pulled a box from the shelves. It held an incense burner. He began to run, and stumbled onto his knees. There were shouts upstairs. He found a shelf marked 4900. A set of golden horns extended from a box. The mask of Yama. Frantically he checked the boxes. They were on the stairs now, shouting. Another row of lights was illuminated, much brighter. Then he had it. Tamdin, the box said. Tamdin, demon costume, Saskya gompa. It was empty.

Someone yelled nearby. There was a white index card taped to the top of the box. He tore it off and ran away from the sounds of the searchers. There was a door up a shorter flight of stairs, showing daylight at the bottom.

It was locked. He rammed it with his shoulder and old wood splintered. He fell outward onto the ground. As he lay blinking in the painful sunlight someone jammed a boot into his back, then reached down and placed handcuffs on his wrists.

The first syllable of weak protest was still on his lips when a truncheon slammed into his forehead, spattering blood. "Hooligan shit," his captor spat before he spoke into a hand radio.

The blood that trickled into his eyes prevented him from seeing how many there were. They were Public Security, he had no doubt, but they seemed confused. From behind him, as he was pushed into a gray van, there were arguments about whose prisoner he was, about his destination. The first two didn't use place names. "The long bed," one of them said. "Wires," argued another. But a third man joined them. "Drabchi," he said, in the tone of an order, referring to the notorious political prison northeast of Lhasa. Prison Number One, it was formally called, where the high-ranking officials of the Tibetan government had once been held.

It was over. Sungpo would die. Shan would have new wardens. Eventually, if Tan did not abandon him, he might be returned to the 404th, with five or ten years added, but only after a Public Security interrogation and the stay in the infirmary that would follow. Who, he wondered in some remote corner of his mind, would be recruited to express the people's disappointment in his socialist development? I'm a hero, Shan would tell his captors. I lasted twelve days on the outside.

The blood was in his mouth now, and the pain of the wound began to surge through his stupor. The van was moving. A siren erupted, painfully loud. They were on a fast road, accelerating. He blacked out. Suddenly there was a shout, and he heard the sound of breaking wood and chickens squawking in terror. He felt the van slam on its brakes and heard the men in front leap out.

There were furious shouts from the front of the van. Then someone climbed into the driver's seat and the van was moving in a Uturn. The siren was cut and the vehicle made a series of a rapid turns, then it pulled to an abrupt stop. The rear doors were flung open and four hands reached in for him. He was half carried, half dragged into the back seat of a car, which instantly pulled away.

Slowly, with dreamlike motions, he wiped the blood from his eyes and pulled himself up. It was a large car, an older American sedan. The driver wore a wool cap over his head. When they pulled into the broad thoroughfare that led out of town the man dangled a small key over his shoulder. As Shan unlocked the handcuffs the man removed the cap to reveal a head of thick blond hair.

"I didn't know-" Shan began, paralyzed by confusion. He pulled out his shirttail to wipe away the blood. "Thank you," he offered in English. "Are you Jansen?"

The man shook his head and muttered to himself in a Scandinavian tongue as he drove slowly through the traffic, careful not to attract attention. "No names," he replied in the same language. "Please. No names." On the floor beside him Shan recognized the bag he had carried to Lhasa. The skull from the cave shrine.

"How could you know?" Shan asked after five minutes.

Jansen had sunk into a depressed silence. "I'm just taking you to the highway somewhere. Your friends will be on the highway, they said."

"Why?"

"Why?" Jansen pounded the steering wheel in anger. "You think I would have done it if I had known? With the knobs as thick as flies? Nobody said anything about knobs. They said for me to be there, that's all. Need to help the gentleman who brought all the information from Lhadrung." He shook his head. "Nothing like this has happened before. Help with the records, no problem. Give an old man a ride from Shigatse, no problem. But this-" He threw up a hand in frustration.

"The purbas," Shan realized. Somehow it had been the purbas. The little man he had seen on the street had not been alone. He had been a purba, Shan now understood. "But how could they know?"

"How do they know anything? Like telepathy."

The knobs had somehow known. The purbas had somehow known. Everyone seemed to know everything. Except him.

"Like telepathy," Shan repeated in a hollow voice. He looked out the window for a fleeting glance of the Potala as it faded into the distance. The precipice of existence.

"Worst they do, they deport me," Jansen muttered to himself.

Shan lay back on the seat. He found a paper towel and held it to his forehead. "There was an obstruction pushed onto the highway," Shan said, as though to himself. "A farmer's cart, I think. The knobs got out to clear the path."

"They told me you need a ride. To wait with my car. Okay, I thought. A ride. I could ask you about the skull shrine. Suddenly one of them runs by. Tosses me a key. For you, he says. Then this Public Security van races down the alley and they throw you inside. Who are you? Why does everyone want you?"

"For me, he said. Did he use my name?"

"No. Not exactly. He said for the pilgrim."

"The pilgrim?"

"The name the purbas are using for you. Tan's pilgrim."

No, Shan was tempted to say. A pilgrim moves toward enlightenment. All I move toward is darkness and confusion. But suddenly a tiny flicker of light appeared. "You said you drove an old man from Shigatse? To Lhadrung?"

Jansen nodded distractedly. He was nervously watching the rearview mirror. "His wife had just died. He sang me some of the old mourning songs."

***

Rebecca Fowler and Tyler Kincaid were waiting fifteen miles out of the city, parked at a flat stretch of highway along the Lhasa River where truckers gathered to sleep. Jansen pulled in behind a decrepit Jiefang truck, from which four young men instantly emerged and escorted Shan to the Americans. Shan turned to thank Jansen, but the Finn just nodded nervously and sped back down the road.

The Jiefang pulled out in front of Kincaid and the driver motioned for the Americans to follow.

Fowler was silent in the front seat. At first he thought she was sleeping but then he saw her hands. They were twisting the road map, their knuckles white.

"It's like free-falling," Kincaid said, with unexpected excitement in his voice. "A hundred feet a second. Your heart's in your throat. The world's flying by." He glanced back at Shan. "It's them, right?" he asked with a huge grin.

"Them?"

"In the truck. The real thing. It's gotta be purbas."

"I'm sorry." Shan felt his forehead. The blood was clotting now.

"Sorry? For this day? The whole damn day, it's been like rappelling down a mountain. You just jump off the cliff and let it happen."

"I never meant for you to be in danger," Shan said. "You should have just left."

"Hell, we made it out alive, didn't we? No sweat. Wouldn't have missed it. We got 'em good, the MFCs. You sent me to search for what isn't there. Perfect. Playing games with their minds." He filled the truck with another of his cowboy whoops.

"Dammit, Tyler," Fowler said. "Get us out of here. It's not over until we're home."

"What do you mean, 'seeking what isn't there'?" Shan asked.

"At the Ministry of Ag. Water resources office moved away in a reorganization. All the files were shipped to Beijing five months ago."

Going to seek what wasn't there. Shan had forgotten the card from the archives. He pulled it from his pocket slowly, as if it would shatter if it moved too fast.

Tamdin, the card said. Saskya gompa. But there was more. On loan, with a date fourteen months earlier, the same date it had been discovered. On loan to Lhadrung town. There was a name, written hastily and smeared. But the chop at the bottom was clear. The personal chop of Jao Xengding. Below it was scrawled "Confirmed," followed by a final ideogram, the inverted, double-barred Y. The same one he had seen on the note from Jao's pocket. Sky, it meant, or heaven.

Twenty miles past the airport the Jiefang truck stopped on a sharp curve and Kincaid pulled in behind it. A man jumped out, ran to the Americans' vehicle, and whispered urgently with Kincaid, pointing to a side road ahead of the truck. The Jiefang turned around and the purba jumped on as it passed by.

Kincaid eased their vehicle into four-wheel-drive and moved onto the side road. "The knobs have road blocks on all roads out of Lhasa, at repeating intervals. They are steaming. They probably have a special reception committee waiting at the Lhadrung County checkpoint. So we have to detour."

He drove recklessly over the rough route, toward the setting sun, then abruptly stopped as the distant flickering lights of Lhadrung valley came into view. "We could go back, you know," Kincaid announced to Shan with a meaningful gaze.

"Back?"

"To Lhasa. The road blocks are checking vehicles leaving the area, not entering. We could do it. You're too valuable to go back to prison when this is over. You know so much. I can help you."

"Help me how?" Shan sensed the American's khata that still hung around his neck.

"Talk to Jansen. We'll calm him down. Hell, he'll want to pick your brain for weeks himself. He knows people who can get you out of the country."

"But Colonel Tan. And if Director Hu-" Fowler protested.

"Hell, Rebecca, they don't know Shan is with us. He just disappears. I could get that tattoo off. I've seen it done. You could be a free man."

A free man. They were such pale words to Shan. It was a concept that Americans always seemed infatuated with, but one which Shan never understood. Perhaps, he reflected, because he had never known a free man. His hand drifted to the khata and slid it off. "You are very kind. But I am needed in Lhadrung. Please, could you just return me to Jade Spring?"

Kincaid saw the scarf in Shan's hand and shook his head in disappointment.

"Keep it," he said admiringly, pushing the khata back. "If you're going back to Lhadrung, you're going to need it."

Chapter Seventeen

Colonel Tan seemed to read the messages from Miss Lihua and Madame Ko simultaneously, his eyes ranging back and forth from the one in his hand to the one on his desk. In the fax from Hong Kong, Miss Lihua reported that she was urgently trying to book flights for her return, but meanwhile wanted to confirm that Prosecutor Jao's personal seal had indeed been taken the year before. No one had been arrested for stealing the chop, although it was the sort of minor act of sabotage typical of monks and other cultural hooligans. A new seal had been fabricated, and a notice sent to alert Jao's bank.

Madame Ko's note reported that she had made inquiries at the Ministry of Agriculture in Beijing, finding a man named Deng who was responsible for the recordkeeping of water rights. Deng knew who Prosecutor Jao was; they had spoken by phone the week before Jao's death, Madame Ko explained. And Deng had an appointment to see the prosecutor during his stopover in Beijing, at a restaurant named the Bamboo Bridge.

"So one of the monks stole Jao's chop and got the costume. Maybe Sungpo, maybe one of the other four," Tan asserted.

"Why his personal seal?" Shan asked. "If I went to all that trouble, and wanted to sow confusion in the government, why not steal his official seal?"

"Opportunistic. A monk saw a chance and broke into the office. An open door or window, and the first thing he found was the personal seal. He got scared and fled. Miss Lihua says it was a monk."

"I don't think so. But that's not the point." Shan found himself gazing out the window toward the street, half expecting to see a truck of knobs arrive to arrest him. There was only the empty car of the officer he had driven to town with. The knobs in Lhasa had known who he was. But they were not coming for him. What had been their orders? Merely to scare him away from Lhasa? To eliminate him if he could somehow be snatched beyond Tan's reach?

"What are you saying?"

Shan turned back toward Tan. "What's important is that the Director of Religious Affairs lied about it. He told us the costumes were all accounted for. He said he checked."

"Someone at the museum may have lied to him," Tan suggested.

"No. Madame Ko checked this morning. No one ever called the museum about the costumes."

"But Jao would never have ordered the costume sent back from Lhasa to Lhadrung. There would be no reason," Tan said tentatively.

"Did you ever hear that his chop was stolen? It would be very disturbing for a prosecutor to lose his seal. Something the military governor should have known about."

"It was only his personal seal."

"I think his personal seal was accessible to someone here in Lhadrung, and they used it to stamp the card that was later put on the museum box."

"You're saying Miss Lihua is lying?"

"We need her back here, right away."

"You saw her note. She's coming." As Tan dropped the fax on the desk, they became aware of Madame Ko standing excitedly at the door, uninvited but apparently unwilling to leave. She raised her hand and made a quick, victorious fist in midair. Tan sighed and gestured for her to enter.

"So Jao was to meet this man Deng in Beijing. For what?" Tan asked.

"To review water permits in Lhadrung," Madame Ko reported. "Jao wanted to know who held the rights before the Americans."

"And Comrade Deng of the Ministry of Agriculture. He had the answer?"

"All the records were still in the original boxes from Lhasa. That's why he was so unhappy that Jao never arrived. Said he had spent hours sorting through them."

"For some stranger from Tibet, he did all that?"

Madame Ko nodded. "Comrade Jao said that if they found what he expected that he would want Deng to go with him straight to the Ministry of Justice headquarters. A big case, he said. Deng would be commended to the Minister himself."

Tan moved to the edge of his seat. "It would have been one of the agricultural collectives," Tan asserted.

"Exactly," Madame Ko confirmed.

"You asked him?"

"Of course. It's part of our investigation," she said with a small conspiratorial nod to Shan.

Tan cast an impatient glance at Shan. "And?"

"Long Wall Farm."

Tan asked for tea. "She acts like she just solved our mystery," he sighed as Madame Ko left the room in an excited bustle.

"Maybe she did," Shan said.

"This Long Wall collective is significant somehow?"

"You recall Jin San, one of the murder victims?"

"Jao prosecuted one of the Lhadrung Five for his murder."

"And in the process discovered that Jin San operated a drug ring."

"Which we eliminated."

"Perhaps you forget that Jin San was the manager of the Long Wall collective."

The colonel lit a cigarette, studying the ember as it burned. "I want Miss Lihua back here," he suddenly barked toward the open door. "Get her a military plane if you have to."

He drew deeply on his cigarette and turned to Shan. "That opium operation is finished, fell apart after Jin San died. Drug sales in Lhadrung have stopped. Drug cases have disappeared at the clinic. I was officially commended."

Shan laid out the photo maps depicting the unexplained license area, the same maps Jao had seen. "Can you read these photos?"

Tan went to his desk and retrieved a large magnifying glass. "I told you. I commanded a missile base," he grunted.

"Yeshe studied the maps yesterday. The new road. The mine. The extra license area to the northwest. He was confused about something. This is the license area for four consecutive months." Shan pointed to the first map. "Winter. Snow. Rocks and dirt. Indistinguishable from the rest of the terrain."

He chose not to speak of Yeshe's other discovery. The computer disks taken by Fowler had indeed been inventories. Half the Chinese-language files had even matched the English files. But the other files had been inventories of munitions, of soldiers, even of missiles located in Tibet. Yeshe's hands had trembled when he gave them to Shan. Together they had taken them to the utility building at Jade Spring Camp and burned them in the furnace. Not for a moment had Shan considered the data on the disks to be genuine. But Yeshe and Shan both knew it made little difference. Public Security was unlikely to be concerned about such a fine point if it found the disks with a civilian. As he had watched the furnace flames, Yeshe had asked for leave to go to the 404th. Civilians were gathering, he had said.

"Not entirely," Tan observed, and used the lens. "There's terracing. Probably very old. But you can see traces of it. Faint shadow lines."

"Exactly. Now, a month later." Shan flipped to the next map. "The slopes are green now, faintly green. But far more so than the rest of the mountains."

"Water. Just means the terraces still catch the water," Tan said.

"But a month later. Look. The color is inconsistent. A blush of pink and red."

Tan silently leaned over the map. He studied it with the lens from several angles. "In the developing process. Sometimes there are anomolies. The chemicals create false colors. Even the lens. It doesn't always react to visible light accurately."

"I think the colors are exact." Shan set down the last map. "Six weeks ago."

"And the colors are gone," Tan observed. "No different from the adjoining slopes. Like I said, a developing fault."

"But the terraces are gone, too."

Tan looked up in confusion, then leaned over the map with his lens.

"Somebody," Shan concluded, "is still growing Jin San's poppies."

***

Shan hated helicopters. Airplanes had always struck him as contrary to the natural order; helicopters seemed simply impossible. The young army pilot who met them at Jade Spring Camp did little to relieve his anxiety. He flew a constant two hundred feet off the ground, creating a roller-coaster effect as they moved over the undulating hills of the upper valley. On Tan's command he banked sharply and began a steep ascent. Ten minutes later they had cleared the ridge and landed in a small clearing.

The terraces were ancient but obvious, built up with rock walls and connected by a worn cart path. Their spring crop had already been harvested. The only sign of life was thin beds of weeds, rising out of the terraces through a carpet of dead poppy leaves.

"The rocks." Tan pointed to a flat rock, then another, and another, all at regular intervals in the fields, ten feet apart. Shan kicked over the nearest. It covered a hole, three inches wide and over twenty inches deep. Tan kicked a second rock, and a third. They all covered similar holes.

Under a high overhanging rock Tan found a stack of heavy wooden poles, eight feet long. He tried one in a hole. It fit perfectly. In the shadows under the rock Shan found the end of a rope. He pulled it without success, then called Tan. Together they heaved and a huge bundle of cloth appeared, wrapped in the rope. No, Shan quickly realized as it emerged into the light, it wasn't cloth. It was a huge military camouflage net.

The silence was broken by a shout from above.

"Colonel!" the pilot called as he ran down the slope. "There was a radio message. They are firing machine guns at the 404th!"

***

Tan ordered the pilot to circle over the prison. There were three emergency vehicles, lights flashing, sitting at the front gate. Four groups of people could be discerned, each clustered together, like pieces of a puzzle waiting to be connected. In the prison compound sitting in a compact square were the prisoners. Shan searched for bodies, for litters of figures being carried to the ambulances, but he found none. Outside the wire in front of the mess hall were the prison guards, in their green uniforms, standing in a crescent facing the prison compound.

A taut gray line of knobs reached around the wire, intersecting the sandbag bunkers. The fourth group was new. Shan studied it as the helicopter landed. They were Tibetans. Herders. People from town. Children, old men and women. Some were facing the compound, chanting mantras. Others were building an offering of butter torma, to be sanctified and lit to invoke the Buddha of Compassion.

The acrid smell of chordite laced the air. As the whine of the helicopter engine faded, Shan heard children crying and heard frantic calls rising from the crowds. They were calling names, calling out to individual prisoners inside the wire. Several old men sat near the front, chanting. Shan listened for a moment. They weren't praying for the survival of the prisoners. They were praying for the enlightenment of the soldiers.

Tan stood in silence, barely containing his fury as he studied the scene. A dozen knobs were deployed in front of the civilians, their submachine guns unslung. Shell casings lay scattered around their feet.

"Who authorized you to fire?" Tan roared.

They ignored him.

"There was movement toward the dead zone," an oily voice said from behind them. "They had been warned." Shan recognized the man even before he turned. The major. "As you are aware, Colonel, the Bureau has procedures."

Tan stared at the major with slow burning eyes, then moved angrily toward the warden, standing with the prison staff. As he did so Shan stepped as close as he dared to the fence, searching the faces of the prisoners. Hands appeared from behind him, one on each arm, and squeezed painfully. His prisoner instincts taking over, he flinched, raising his arm over his face, to prepare for a blow. When none came, he let himself be pulled away by the soldiers. The knobs, he realized, didn't recognize him as a prisoner. His hand moved to his sleeve, pulling it down to cover his tattoo.

He stood where they deposited him, staring through the wire. There was no sign of Choje.

The Tibetan civilians pulled away as he walked through the crowd, shunning him, refusing to let him close enough to speak. "The prisoners," he called out to the backs that were turned to him. "Are prisoners hurt?" he called out.

"They have charms," someone shouted defiantly. "Charms against bullets."

Suddenly a familiar figure was in front of him, looking strangely out of place. It was Sergeant Feng, wearing the old woolen shirt Shan had put on him in Kham, his face covered with grime and fatigue. When his eyes met Shan's, there was no arrogance left in them. For a passing moment Shan thought he saw pleading in them.

"I thought you were in the mountains."

"Been there," Feng replied soberly.

As Shan moved toward him, Feng stepped forward, as though to block him. Shan put his hand on Feng's shoulder and pushed him aside. There was a priest on the ground behind him, saying a mantra with an old woman. He stopped and stared. It was Yeshe, he suddenly realized, wearing a red shirt that gave the impression of a robe. He had cropped his hair to the scalp.

Yeshe grinned awkwardly when he saw Shan. He patted the woman's hand and stood.

"I was asking about the prisoners," Shan said.

Yeshe gazed toward the wire. "They fired over their heads. No one injured yet." There was a self-assurance in his eyes which Shan had not seen before.

"Damn the fool!" the sergeant suddenly spat from behind them. He began running through the crowd to a cooking fire where a woman was arguing with someone. It was Jigme.

"She won't give me anything," Jigme said as soon as he saw Shan. "I told her, it's for Je Rinpoche." He looked at Shan, then to Yeshe. "Tell her," he pleaded, "tell her I'm not Chinese."

"You were at the mountain," Shan said. "What happened?"

"I need to find herbs. A healer. I thought maybe here. Someone said priests would be here."

"A healer for Je?"

"He's very sick. Very weak. Like a leaf on a rotting stem. Soon he will just float away," Jigme said with a forlorn tone, his eyes hooded and moist, like those of a mourner. "I don't want him to go. Not Rinpoche too. Don't let him go. I beg you." He grabbed Shan's hand and squeezed it painfully tight.

A whistle blew. The knobs snapped to attention as a government limousine appeared. Li Aidang jumped out and threw a jaunty, abbreviated salute to the major, then strode over to Tan. They spoke a moment, then Li joined the major along the line of knobs, as though inspecting a parade.

Shan pushed Sergeant Feng aside. "Go to town," he said urgently. "Get Dr. Sung. Get her to the barracks."

Colonel Tan stood as if waiting for Shan, silently watching the civilians.

"Why do the lessons come so hard?" the colonel asked quietly. "Nearly fifty years and still they don't understand. They know what we have to do."

"No," said Shan. "They know what they have to do."

Tan showed no sign of having heard him.

Shan turned to him, fighting the temptation to run back to the fence. "I have to go inside."

"In front of the commandos' guns? Like hell."

"I have no choice. These are my– we can't let them die."