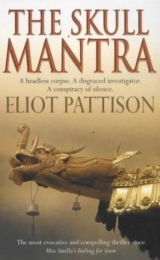

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"You, of course."

"I wonder." She sipped her tea. "If it wasn't your prisoner who killed Jao, then who was the murderer?"

"Your demon. Tamdin."

Fowler's head snapped up. She looked around to see if her staff was listening. They were gathered at the far end of the room. "No one jokes about Tamdin," she said in a low voice, suddenly tinged with worry.

"I wasn't."

"Every village, every sheepcamp around here has been telling stories of demons visiting. Last month there were complaints about our blasting. They said it must have awakened him. There was a work stoppage for half a day. But I explained that we only began blasting six months ago."

"Blasting for what?"

"Dikes. A new pond."

Shan shook his head in bewilderment. "But why build ponds? Why all this water? How can you produce minerals? There is no mine."

Fowler smiled. "Sure there is," she said, seeming relieved to change the topic. "Right out the front door." She grabbed a pair of binoculars and gestured for him to follow. She led Shan outside along a path that rimmed the largest pond, walked briskly to the center of the largest dike, the one that was built across the mouth of the valley, then paused for Yeshe and Sergeant Feng to catch up. "This is a precipitation mine."

"You mine rain?" Yeshe asked.

"Not what I meant. But I guess that's one way to describe it. We mine the rain of a hundred centuries ago." She pointed across the ponds. "This plain is the bottom of a bowl. No outlet but the Dragon Throat, and it was blocked up here by an ancient landslide. It's a volatile geology. The surrounding peaks were volcanic. Lava flowed down the slopes. Lava is filled with the light elements. Boron. Magnesium. Lithium. Over centuries rains dissolved the lava and washed the salts into the bowl. A salt lake would build up. In time of drought a crust would form over the lake. A foot thick. Sometimes five feet thick. Then a cycle of wet years would fill the basin with water again, with the dissolved minerals. Then another crust. Every few centuries another eruption would replenish the slopes. It's how the Great Salt Lake in America was formed."

"But these lakes are manmade."

"The natural salt lake is there. In fact, eleven of them. In layers, underneath us. We just moved clay to build surface ponds. We pump up the brine into our ponds for evaporation." Fowler pointed toward three small sheds across the valley floor, ganglia in a network of pipes. "Three wells do all the work."

"But where is your plant?"

"In the ponds. With the right concentration we can precipitate out boron particles. Each lake is periodically drained and we harvest the product that has accumulated on the bottom. The trick is to maintain the concentration. Get it wrong and we wind up with table salt. Or a stew of metals too expensive to separate."

She led them down the dike to where it intersected the gully of the Dragon's Throat.

"But you said it was a landslide that blocked the valley," Shan said.

"We moved it. Too unstable. The dam needs to be packed clay. Just finished this one, our last dike." Shan saw that the pond beside them, noticeably lower than the others, was still being filled by the wells. The American pointed toward the far end of the plateau and handed Shan the binoculars. "The farthest pond is being harvested."

There was a mound of brilliant white material near the pond.

"We have a crude processing unit, to slightly refine the product. Once we start production, we will seal it into one-ton bags and ship it to the world." He realized she was looking elsewhere as she spoke, toward a cluster of workers in the middle of the pond complex. He turned the binoculars to the workers and saw that it was two separate groups. Neither seemed to be working.

"The world?" he asked.

"Some to factories in China," she said distractedly. "Much of it to Hong Kong for shipping to Europe and America."

Shan studied the dull gray equipment beside the second group. "Why would Tan send them when your permit is suspended?"

"The Ministry of Geology suspended the permit."

"Who signed the order?"

Rebecca Fowler paused, as though considering whether to respond. "Director Hu."

"Of the local Ministry of Geology office?"

"Right. But I explained to Tan that if we shut down now, we lose all the material in the ponds. We design the process so our commercial products precipitate first. If we wait, they get contaminated. Could lose six months' work. He agreed we should continue to process our sample batches on the grounds that the permit only applies to commercial scale production."

"But then everything stops?"

"Unless we can figure out what's going on."

"You're saying Hu gave no reason for the suspension?"

It was as far as Fowler would go. She took two steps away and looked up at a rock face at the end of the pond. Shan studied her for a moment, trying to understand if she was upset because of Prosecutor Jao, Director of Mines Hu, or himself, then followed her gaze to the rock. The cliff rose at least three hundred feet, nearly perpendicular. Suddenly he saw movement on the rocks, two white ropes dangling down the face from the top.

Fowler turned to look at the gully. "You can see all the way to the valley," she observed.

But Shan did not turn. The ropes were moving. There were two figures at the top, in brilliant red vests and white helmets.

Suddenly Yeshe called out with surprise. He was looking down the Dragon's Throat. "The 404th! You can see-" He caught himself and cast an embarrassed glance toward Shan, who swung the binoculars around. It took only a moment to follow the Dragon's Throat to the base of the range. They were twenty miles away by tortuous mountain road, but there in plain view was the 404th's worksite, no more than three miles distance as a raven would fly. Adjusting the focus, he picked out Tan's bridge, the tanks of the knobs, and the long rank of prison trucks.

He felt the glare of the American and lowered the glasses.

"My chief engineer showed it to me," she said with an accusing tone. "It's one of your prison projects. Slave labor."

"The government often assigns compulsory work crews to road construction," Yeshe said, suddenly self-righteous. "Beijing says it builds socialist awareness."

"I've been talking to the UN about it."

"Personally," Shan said, "I am in favor of international dialogue." He felt a sharp gun-barrel jab in his back. Sergeant Feng had arrived behind him. Shan turned. Feng's thumb was extended toward Shan and his eyes were smoldering.

The action was not missed by Fowler. She seemed about to say something when suddenly a loud whoop echoed across the rock face. They turned to see the two figures dropping down the cliff on the ropes, kicking off the rock as they fell.

"Crazy fool," Fowler muttered. "It's Kincaid. He's teaching the young engineers. He's going to do Everest before his tour is finished. Wants to go up with a team of Tibetans."

"Everest?" Yeshe asked.

"Sorry," Fowler said. "Chomolungma is what you call it. Mother mountain."

"It means 'goddess mother of the world,' " Yeshe corrected.

As the figures landed at the base of the cliff, they made exhilarated leaps into the air and embraced. Moments later they began moving onto the long dike, the lean man with brilliant eyes and ponytail Shan had seen at the cave and the young Tibetan Shan had seen driving the truck and later at Tan's office.

"I'm Tyler," the American introduced himself. "Tyler Kincaid. Just Kincaid will do." His smile faded as he saw Sergeant Feng. His eyes settled on the sergeant's pistol. "This," he said with a distracted jerk of his thumb, "is Luntok, one of our engineers."

"Kincaid works the magic in the ponds," Fowler explained.

"Nature does the magic," Kincaid said impassively. He spoke with a slight drawl, the way Shan had heard characters speak in American westerns. "I just give her the opportunity."

He studied Shan, then lowered his voice. "You were at the cave. With Tan," he said with a tone of accusation. "We want to know about that cave."

"So do I. I need to know why you were there."

"Because something is wrong there. Because it's a holy place," he said.

"Why would you say that?" Shan asked.

"It is one of those places the Buddhists call a place of power. At the end of a valley. Facing south. A spring nearby. A large tree."

"So you've been there before?"

Kincaid make a sweeping gesture toward the mountains. "We climb a lot of ridges. Luntok saw the trucks. But we didn't need to see them to know it might be important. The topography shows it all."

Suddenly an airhorn blew, a long unceasing howl that hurt the ears. A worker appeared beside Fowler, panting from a run across the dike. "They're going to fight!" he shouted. "They're going to destroy the equipment!"

"Goddamned MFCs!" Tyler snapped at Fowler. "I told you!" He darted toward the trouble, Luntok close behind.

The Tibetan workers had formed a line in the middle of the valley. A huge gray bulldozer on which half a dozen of Tan's engineers perched had been stopped by a makeshift barricade of smaller trucks and earthmovers. The soldiers were firing the bulldozer's airhorn in staccato blasts, like a machine gun. The Tibetans sat cross-legged on the ground in front of the vehicles.

Kincaid appeared between the lines, standing with the Tibetans, haranguing the soldiers.

Shan offered Rebecca Fowler the binoculars. She seemed reluctant to take them. "I never meant for this-" she began. "If anyone got hurt I couldn't live with myself." She turned to him, as if surprised to have said the words to Shan. Anguish filled her eyes. "Make them leave."

"Who?"

"The soldiers. Tell Tan we'll find some other way to meet the schedule."

"I am sorry. I have no authority."

"Of course you do," Yeshe suggested. "You are a direct representative of Colonel Tan. You will report any impropriety to him." Yeshe seemed torn by indecision, then bolted toward the soldiers. He was not about to have an incident at the mine delay completion of his assignment. He was, Shan reminded himself, a man with a destination.

The soldiers began raising and lowering the blade of their bulldozer, giving the machine the appearance of a hungry monster, impatient to chew its food. Kincaid moved back and forth, vigorously gesturing at the ponds, at the mountains, and the equipment sheds.

"Mr. Kincaid," Shan observed, "is an unusually zealous man." He saw Fowler's confused glance. "For a mining engineer."

"Tyler Kincaid is a treasure. Could have his pick of jobs in the company. New York. London. California. Australia. He chose Tibet. Is he zealous? We're eight thousand miles from home, trying to open a mine with unproven technology in an unproven location with an unproven workforce. Zealousness struck me as something of a credential."

"His pick of jobs. Because he is so qualified?"

"That, and his father owns the company."

Shan watched Tyler Kincaid as he moved to the lead soldier and shook him by the shoulders. His father owned the company, and Kincaid was at what had to be the most remote, inaccessible outpost of the company anywhere on the planet. "He said something. MFCs. What does it mean?"

"Just his way of talking."

"Talking about what?"

"Bureaucrats, I guess." She saw that he would not give up, and shrugged. "An MFC is a Mother Fucking Communist," she explained, and turned back toward the workers with an amused grin.

Yeshe arrived in front of the soldiers and began pointing toward Shan. The bulldozer blade stopped and the soldiers peered toward the dike in obvious uncertainty. Kincaid used the reprieve to dart to the administration building, from where he reappeared at full speed carrying a black box. Fowler raised the glasses for a moment, gave a grunt of amusement, and handed them to Shan.

Kincaid had a portable tape player. He set it in front of the bulldozer and began playing American rock music, so loud Shan could hear it from the dike. The American engineer began to dance.

At first both sides just stared. Then a soldier began to laugh. Another soldier joined the dance, then one of the Tibetans. The others all began laughing.

Fowler sighed. "Thanks," she said, as if Yeshe's intervention hadbeen Shan's idea. "Crisis averted. Problem still not solved," she said, and began walking toward the office.

Shan moved to her side. "Have you thought about a priest?" he asked.

"A priest?"

"The Tibetans won't work because they believe something has released a demon."

Fowler shook her head sadly, surveying the valley. "Somehow I can't believe it. I know these people. They aren't pagans."

"You misunderstand. It's not that most of them believe a monster is roaming the hills. What they believe is that the balance has been disturbed, and an imbalance produces evil. The demon is just a manifestation of that evil. It could be manifested in a person, in an act, even an earthquake. The balance can be restored with the right rituals, the right priest."

"You're saying all of this is symbolic? Jao's murder wasn't symbolic."

"I wonder."

She turned to gaze down the Throat as she considered Shan's suggestion. "The Religious Bureau would never permit a ritual. The director is on our board."

"I was not suggesting a Bureau priest. You would need someone special. Someone with the right powers. Someone from the old gompas. The right priest would make them understand they have nothing to fear."

"Is there nothing to fear?"

"I believe your workers have nothing to fear."

"Is there nothing to fear?" the American woman repeated, threading her fingers through her auburn hair.

"I don't know."

They walked on in silence.

"It's not exactly something that was covered in my environmental impact statements," Fowler said.

"It was not necessarily the result of your mining work."

"But I thought that was the whole-"

"No. Something happened here. Not Jao's murder, because so few know about it. Something else. Something was seen. Something that scared the Tibetans, that had to be explained to their way of thinking. A ready explanation would be the excavation of the mountain. Every rock, every pebble has its place. Now the rocks and pebbles have been moved."

"But the murder is involved, isn't it." It was not a question. "The demon. Tamdin." Her voice was almost a whisper now.

"I don't know." Shan studied her. "I did not realize you were so upset about the murder."

"It's got me spooked," she said, looking back at the workers. The machines were backing away from each other. "I can't sleep at night." She looked back at Shan. "I'm doing strange things. Like talking to total strangers."

"Is there something else you need to tell me?" As they approached the compound, Shan noticed movement at the end of the farthest building. A line of Tibetans extended out of a side door, mostly workers but also old women and children in traditional dress.

Rebecca Fowler seemed not to notice. "It's just that I keep thinking that they're connected. My problem and yours."

"You mean Prosecutor Jao's murder and the suspension of your permit?"

Fowler nodded slowly. "There is something else, but now with my permit suspended it will just sound spiteful. Jao was on our supervisory committee. Before he left here on his last visit, Jao had a big argument with Director Hu of the Ministry of Geology. After the meeting, outside, Jao was yelling at Hu. It was about that cave. Jao said Hu had to stop what he was doing at the cave. He said he would send in his own team."

"So you knew about the cave before their argument?"

"No. I didn't understand their argument. But later Luntok mentioned the trucks he had seen. I didn't connect any of it until I went to the site that day. Even then I was so upset with Tan that it was only afterward I remembered Jao's argument with Hu."

They were nearly at the truck, where Yeshe and Sergeant Feng waited. She paused and spoke with a new, urgent tone. "How do I find the priest I need?"

"Ask your workers," Shan suggested. Was it possible, he wondered, that she would defy Hu, even Tan, to keep her mine open?

"I can't. It would make it official. Religious Affairs would be furious. The Ministry of Geology would be furious. Help me find one. I can't do it myself."

"Then ask the mountaintops."

"What do you mean?"

"I don't know. It's a Tibetan saying. I think it means pray."

Rebecca Fowler grabbed his arm and looked at him desperately. "I want to help you," she said, "but you can't lie to me."

He responded only with an awkward, crooked smile then looked longingly toward the distant peaks. He would never lie to her but he would always believe the lies to himself if they were his only hope of escape.

Chapter Seven

News flash," Sergeant Feng muttered to the commando in battle fatigues who stood at the 404th gate. "The Taiwan invasion is going to be on the coast, not in the Himalayas."

The 404th had the appearance of a war zone. Tents had been erected along the perimeter. New wire had been strung on top of the barbed fence already in place, a vicious-looking strand with razor-sharp strips of metal dangling from it. The electricity had been cut off, except for the wire leading to a new bank of spotlights at the gate, leaving the compound in shadow as the last glimmer of dusk faded across the valley. Bunkers of sandbags were being built for machine guns, as if the Bureau troops expected a frontal assault. A freshly painted sign declared that a fifteen-foot strip inside the fence was now the dead zone. Prisoners entering the zone without authorization could be shot without warning.

The commando raised his AK-47 rifle. There was a raw, animal quality in his countenance that made Shan shiver. Sergeant Feng shoved Shan violently through the gate, knocking him to his knees. The knob studied Feng a moment, then, with a reluctant frown, stepped back.

"Got to show them who's in charge," Feng mumbled as he caught up with Shan. Shan realized it was meant to be an apology. "Damned strutting cockbirds. Grab the glory and move on." He stopped, arms akimbo, to survey the knobs' bunkers, then gestured toward Shan's hut. "Thirty minutes," he snapped, and moved back toward the brilliantly lit dead zone.

The air of the blackened hut was thick with the smell of paraffin. There was a sound as though of mice scampering on a rock floor. Beads were being worked. Someone whispered Shan's name and a candle was lit. Several prisoners sat up and stared, breaking the count of their beads. Their faces were shadowed with fatigue. But on some there was also something else. Defiance. It scared Shan, and excited him.

Trinle was on his feet as soon as he saw Shan.

"I must speak with him," Shan said urgently. Choje was on the bunk behind Trinle, as still as death.

"He is near exhaustion."

Suddenly Choje's hands moved and folded over his mouth and nose. He exhaled sharply three times. It was the ritual of awakening for every devout Buddhist. The first exhalation was to expunge sin, the second to purge confusion, the third to clear away impediments to the true path.

Choje sat up and greeted Shan with a flicker of a smile. He was wearing a robe, an illegal robe, which had been sewn together from prison shirts and somehow dyed. Without speaking he rose and moved to the center of the floor where he dropped into the lotus position, joined by Trinle. Shan sat between them.

"You are weak, Rinpoche. I did not mean to disturb your rest."

"There is so much to be done. Today each hut did ten thousand rosaries. Many of the men have been prepared. Tomorrow we will try for more."

Shan clenched his jaw, fighting his emotions. "Prepared?"

Choje only smiled.

A strange scraping noise disturbed the stillness. Shan turned. One of the young monks was reverently spinning a prayer wheel, fashioned from a tin can and a pencil.

"Are you eating?" Shan asked.

"The kitchens were ordered closed," Trinle explained. "Only water. Buckets are left at the gate at midday."

Shan pulled the paper bag that contained his uneaten lunch from his coat pocket. "Some dumplings."

Choje received the bag solemnly and handed it to Trinle to divide. "We are grateful. We will try to get some to those in the stable."

"They opened the stable," Shan whispered. It was not a question but an anguished declaration.

"Three of the monks from a gompa to the north. They sat near the gate, demanding an exorcism."

"I saw the troops outside. They look impatient."

Choje shrugged. "They are young."

"They will not grow old waiting for striking prisoners."

"What can they expect? There is an angry jungpo. It would be but the work of a day to restore the balance."

"Colonel Tan will never allow an exorcism on the mountain. It would be a defeat, an embarrassment."

"Then your colonel will have to live with them both." There was no challenge in Choje's voice, only a trace of sympathy.

"Both," Shan repeated. "You mean Tamdin."

Choje sighed and looked about the hut. There was another unfamiliar sound. Shan turned and saw the khampa, sitting by the door. The man had a frightening gleam in his eyes.

"Gonna get us out, wizard?" he asked Shan. He had removed the handle from his eating mug and was sharpening it on a rock. "Another of your tricks? Make all the knobs disappear?" He laughed, and kept sharpening.

"Trinle has been practicing his arrow mantras," Choje observed as he watched the khampa with sad eyes. An arrow mantra was a charm of ancient legend, by which the practitioner was transported across great distances in an instant. "He is getting very good. One day he will surprise us. Once when I was a boy I saw an old lama perform the rite. One moment there was a blur and he was gone. Like an arrow from a bow. He was back an hour later, with a flower that grew only at a gompa fifty miles away."

"So Trinle will leave you like an arrow?" Shan asked, unable to disguise his impatience.

"Trinle knows many things. Some things must be preserved."

Shan sighed deeply to calm himself. Choje was speaking as though the rest of their world would not survive. "I need to know about Tamdin."

Choje nodded. "Some are saying that Tamdin is not finished." He looked sadly into Shan's eyes. "He will not show mercy if he strikes again. In the time of the seventh," Choje said, referring to the seventh Dalai Lama, "an entire Manchurian army was destroyed as they invaded. A mountain collapsed on them as they marched. The manuscripts say it was Tamdin who pushed the mountain over."

"Rinpoche. Hear my words. Do you believe in Tamdin?"

Choje looked at Shan with intense curiosity. "The human body is such an imperfect vessel for the spirit. Surely the universe has room for many other vessels."

"But do you believe in a demon creature that stalks the mountains? I must understand if– if there is to be any chance of stopping all this."

"You ask the wrong question." Choje spoke very slowly, in his prayer voice. "I believe in the capacity of the essence that is Tamdin to possess a human being."

"I do not understand."

"If some are meant to achieve Buddhahood then perhaps others are meant to achieve Tamdinhood."

Shan held his head in his hands, fighting an overwhelming fatigue. "If there is to be hope I must understand more."

"You must learn to fight that."

"Fight what?"

"This thing called hope. It still consumes you, my friend. It makes you wrongly believe that you can strike against the world. It distracts you from what is more important. It makes you believe the world is populated by victims and villains and heroes. But that is not our world. We are not victims. Rather we are honored to have had our faith tested. If we are to be consumed by the knobs then we are to be consumed. Neither hope nor fear will change that."

"Rinpoche. I do not have the strength not to hope."

"I wonder about you sometimes," Choje said. "I worry that you are too hard a seeker."

Shan nodded sadly. "I do not know how not to seek."

Choje sighed. "They are holding a lama," he observed. "A hermit from Saskya gompa."

Shan had long ago given up trying to understand how information spread through the Tibetan population and across prison walls. It was as if the Tibetans practiced a secret form of telepathy.

"Did this lama do it?" Choje asked.

"You think a lama could do such a thing?"

"Every spirit can lapse. Buddha himself wrestled with many temptations before he was eventually transformed."

"I have seen this lama," Shan said solemnly. "I have looked into his face. He did not do it."

"Ah," Choje sighed, and then was silent. "I see," he said after a long time. "You must obtain the release of this lama by proving that the murder was done by the demon Tamdin."

"Yes," Shan admitted at last, looking into his hands, his reply barely audible.

The two men sat in silence. From somewhere outside the hut came a long disembodied groan of pain.

***

Yeshe refused when Shan explained his task the next morning. "I could get arrested just for asking about a sorcerer," he complained.

Feng was driving them through the low rolling hills of gravel and heather that led to town. A meandering line of willows and high sedges marked the path of the river that, having cascaded through the Dragon's Throat, moved at a more languid pace down the valley. They passed a field where bulldozers had flattened a hill, cultivated with rows of now dying plants, so twisted and contorted by the wind and dryness that they were unidentifiable. Another failed attempt to root something from the outside that Tibet neither needed nor wanted.

"What did they punish you for?" Shan asked Yeshe. "Why were you sentenced to a labor camp?"

Yeshe would not reply.

"Why do you still fear them? You've been released."

"Every sane person fears them." Yeshe smirked pointedly.

"It's your travel papers, is that what troubles you? You think you won't get them if you work with me. Without new travel papers you'll never get out of Tibet, never get a job in Sichuan fitting your station, never get your shiny television."

Yeshe seemed to resent the comment. But he didn't deny it. "It's wrong to encourage these people who cast spells," he said. "They hold Tibet in another century. We will never progress."

Shan stared at Yeshe but did not reply. Yeshe shifted in his seat and scowled out the window. A woman, enveloped in a huge brown felt cloak, walked down the road, leading a goat on a rope.

"You want a history of Tibet?" Yeshe asked sullenly, still facing the window. "Just one long struggle between priests and sorcerers. The church demands that we strive for perfection. But perfection is so difficult. Sorcerers offer shortcuts. They take their power from the weakness of the people and the people thank them for it. Sometimes the priests rule, and they build up the ideal. Then the sorcerers rule. And in the name of the ideal the sorcerers ruin it."

"So that is what Tibet is about?"

"It's what keeps society moving. China, too. You have your sorcerers. Only you call them secretary this and minister that. With a little red book of charms written by the chairman himself. The Master Sorcerer."

Yeshe looked up, aghast, suddenly aware that Feng may have heard. "I didn't mean-" he sputtered, then clenched his fists in frustration and turned to the window again.

"So these students of Khorda, they scare you?" Shan asked. Maybe they should all be scared, he realized. If you want to reach Tamdin, Choje had suggested, speak to the students of Khorda.

"Students? Who said students? No need. People are always talking about the old sorcerer. He lives. If that's what you call it. They say he doesn't need to eat. Some say he doesn't even need to breathe. But we'll have to find his lair."

"Lair?"

"His hiding place. Could be a cave deep in the mountains. Could be in the market place. He is very secretive. He moves about, from shadow to shadow. They say he can disappear into thin air, like a wisp of smoke. It may take some time."

"Good. The sergeant and I are going to the restaurant, then to Prosecutor Jao's house. After that, the colonel's office. Meet us there when you find your sorcerer."

"This Khorda, he will never talk to an investigator."

"Then tell him the truth. Tell him I am a troubled man badly in need of magic."

***

They tried to close the restaurant when Shan arrived. "You knew Prosecutor Jao?" he called to the head waiter through a crack in the door.

"I knew. Go away."

"He ate here with an American five nights ago."

"He ate here often."

Shan put his hand on the door. The man moved as though to push it shut, then saw Sergeant Feng and relented, trotting back down the front hallway.

Shan stepped inside and followed the shadow of the fleeing waiter. In the hallway busboys cowered. In the kitchen no one would look at him.

He caught up with the man as he reentered the dining room through a side door. "Did someone bring a message that night?" Shan asked the waiter, who was still beating his awkward retreat, picking up trays and nervously setting them down a few steps later, then pulling a stack of plates from the counter.

"You!" Sergeant Feng shouted from the doorway.

As the man flinched, the plates slipped from his grip, shattering on the floor. He stared at the plates forlornly. "No one remembers. It was busy."

The man began shaking.

"Who has been here? Somebody was already here. Somebody said don't speak to me."

"No one remembers," the waiter repeated.

As Feng took a step inside the door, Shan raised a palm in resignation and walked away.

"Who's going to pay for the plates?" the waiter moaned behind him. Shan could still hear him, sobbing like achild, as he moved out the door and back into the truck.

Prosecutor Jao had lived in a small cottage in the government compound on the new side of town, a square stucco structure with two rooms and a separate kitchen. In Tibet it was the equivalent of a grand villa.

Shan lingered at the entrance, making a mental note of the way the heather along the wall of the house had been recently trampled. The door was slightly ajar. He pushed it with his elbow, careful not to smudge any prints that might be on the handle. Here, he hoped, could be the answer to why Prosecutor Jao had detoured to the South Claw. Or at least, the picture of Jao the private man that would help Shan understand his motivations.