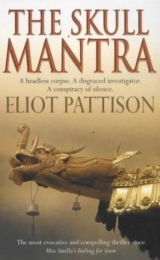

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"They say the chairman himself sent you here," the sergeant finally said as the low, flat buildings of the town came into view.

Shan didn't reply. He bent in his seat trying to roll up his cuffs. Someone had produced a pair of worn, oversized gray trousers for him to wear, and a threadbare soldier's jacket. They had made him change clothes in the middle of the office. Everyone had stopped his work to watch.

"I mean, why else would they put you in with them?"

Shan straightened. "I'm not the only Chinese."

Feng grunted as though amused. "Sure. Model citizens, every one. Jilin, he killed ten women. Public Security would have put a bullet in him except his uncle was a party secretary. That one from Squad Six, he stole the safety gear from an oil rig in the ocean. To sell in the black market. Storm came and fifty men died. Letting him have a bullet was too easy on him. Special cases, you from home."

"Every prisoner is a special case."

Feng grunted again. "People like you, Shan, they just keep for practice." He stuffed two slices of apple into his mouth. Momo gyakpa, he was called behind his back, fat dumpling, for the curve of his belly and the way he was always scavenging food.

Shan turned away. He looked over the expanse of heather and hills rolling like a sea toward the high ice-clad ranges. It offered the illusion of escape. Escape was always an illusion for those who had no place to escape to.

Sparrows flitted among the heather. There were no birds at the 404th. Not all the prisoners were fastidious in respecting life. They claimed every crumb, every seed, nearly every insect. The year before there had been a fight over a partridge that was blown into the compound. The bird had narrowly escaped, leaving two men with a handful of feathers each. They had eaten the feathers.

The four-story building that housed the government of Lhadrung County had a crumbling synthetic marble facade and filthy windows in corroded frames that rattled in the wind. Feng pushed Shan up the stairs to the top floor, where a small gray-haired woman led them to a waiting room with one large window and a door at each end. She scrutinized Shan with a twist of her head, like a curious bird, then barked at Feng, who shrank, then sullenly removed the manacles from Shan's wrists and retreated into the hallway.

"A few minutes," she announced, nodding at the far door. "I could bring you tea."

Shan looked at her dumbfounded, knowing he should tell her of her mistake. He had not had tea, real green tea, for three years. His mouth opened but no sound came out. The woman smiled and disappeared behind the near door.

Suddenly he was alone. The unexpected solitude, however brief, overwhelmed him. The imprisoned thief suddenly left alone in a treasure vault. For solitude had been his real crime during his years in Beijing, the one for which no one had ever thought to prosecute him. Fifteen years of postings away from his wife, his private apartment in the married quarters, his long solitary walks through the parks, the meditation cells at his hidden temple, even his irregular work hours had given him a hoard of privacy unknown to a billion of his countrymen. He had never understood his addiction until that wealth had been wrenched away by the Public Security Bureau three years before. It hadn't been the loss of freedom that hurt most, but the loss of privacy.

Once in a tamzing session at the 404th he had confessed his addiction. If he had not rejected the socialist bond, they said, there would have been someone there to stop him. It wasn't friends that mattered. A good socialist had few friends, but many watchers. After the session he had stayed behind in the hut, missing a meal just to be alone. Discovering him there, Warden Zhong had dispatched him to the stable, where they broke something small in his foot, then forced him back to work before it could heal.

He examined the room. A huge plant extending to the ceiling occupied one corner. It was dead. There was a small table, polished brightly, with a lace doily on top. The doily caught him by surprise. He stood before it with a sudden aching in his heart, then pulled himself away to the window.

The top floor gave a view over most of the northern quarter of the valley, bound on the east by the Dragon Claws, the two huge symmetrical mountains from which ridges splayed out to the east, north, and south. The dragon had perched there and taken phantom form, people said, its feet turned to stone as a reminder that it still watched over the valley. What was it someone had shouted when the American's body was found? The dragon had eaten.

He pieced together the geography until at last, across an expanse of several miles of windblown gravel and stunted vegetation he discerned the low roofs of Jade Spring Camp, the county's primary military installation. Just above it, and below the northernmost Claw, was the low hill that separated Jade Spring from the wire-enclosed compound of the 404th.

Almost without thinking Shan traced the roads, his work of the past three years. Tibet had two kinds of roads. The iron roads always came first. The 404th had laid the bed for the wide strip of macadam that ran from Lhasa, beyond the western hills, into Jade Spring Camp. Iron roads were not railways, of which Tibet had none. They were for tanks and trucks and fieldguns, the iron of the People's Liberation Army.

The thin line of brown that Shan traced from an intersection north of town toward the Claws was not such a road. It was far worse. The road the 404th was building now was for colonists who would settle in the high valleys beyond the mountains. The ultimate weapon wielded by Beijing had always been population. As in the western province of Xinjiang, the home of millions of Moslems belonging to central Asian cultures, Beijing was turning the native population of Tibet into a minority in their own lands. Half of Tibet had been annexed to neighboring Chinese provinces. Population centers in the rest of Tibet had been flooded with immigrants. Endless truck convoys over thirty years had turned Lhasa into a Han Chinese city. The roads built for such convoys were called avichi trails at the 404th, for the eighth level of hell, the hell reserved for those who would destroy Buddhism.

A buzzer sounded. Shan turned to find the birdlike woman standing with a cup of tea. She extended the cup, then scurried through the far door, disappearing into a darkened room.

He gulped down half the cup, ignoring the pain as it scalded his throat. The woman would realize her mistake and take it back. He wanted to remember the sensation, to relive the taste in his bunk that night. Even as he did so he felt demeaned, and angry at himself. It was a prisoner's game that Choje warned against, stealing bits of the world to worship back in the hut.

The woman reappeared and gestured for him to enter.

A man in a spotless uniform sat behind an unusually long, ornate desk lit by a single gooseneck lamp. No, it was not a desk, Shan realized, but an altar that had been converted to government use.

The man silently studied Shan while lighting an expensive American cigarette. Loto gai. Camels.

Shan saw the familiar hardness. Colonel Tan's face looked like it had been chiseled out of cold flint. If they were to shake hands, Shan thought, Tan's fingers would probably slice through his knuckles.

Tan exhaled the smoke through his nose and looked at the teacup in Shan's hands, then to the gray-haired woman. She turned to open the curtains.

Shan did not need the sunlight to know what was on the walls. He had been in scores of such offices all over China. There would be a photograph of the rehabilitated Mao, pictures of military life, photos of a favorite command, a certificate of appointment, and at least one Party slogan.

"Sit," the colonel ordered, gesturing to a metal chair in front of the desk.

Shan did not sit. He examined the walls. Mao was there, not the rehabilitated one but a photo from the sixties, one that showed the prominent mole on his chin. The certificate was there, and a photograph of grinning army officers. Above them was a picture of a nuclear missile draped with the Chinese flag. For a moment Shan did not see a slogan, then he saw a faded poster behind Tan. "Truth," it said, "Is What the People Need."

Tan opened a thin, soiled folder and fixed Shan with an icy stare.

"In Lhadrung County the state has entrusted the reeducation of nine hundred and eighteen prisoners to me." He spoke with the smooth confident voice of one accustomed to always knowing more than his listeners. "Five lao gai hard labor brigades and two agricultural camps."

There was something Shan had not seen at first, fine wrinkles below the close-cropped graying hair, a trace of weariness around the mouth. "Nine hundred and seventeen have files. We can tell where each was born, their class background, where each was first informed against, every word uttered against the state. But for the other one there is only a short memorandum from Beijing. Only a single page for you, prisoner Shan." Tan folded his palms over the folder. "Here by special invitation of a member of the Politburo. Minister of the Economy Qin. Old Qin of the Eighth Route Army. Sole survivor of Mao's appointees. Sentence indefinite. Criminal conspiracy. Nothing more. Conspiracy." He pulled on the cigarette, studying Shan. "What was it?"

Shan held his hands together and stared at the floor. There were things far worse than the stable. Zhong didn't need Tan's permission to send him to the stable. There were prisons where inmates never left their cells except in death. And for those whose ideas were truly infectious, there were secret medical research institutes run by Public Security Bureau doctors.

"Conspiracy to assassinate? Conspiracy to embezzle state funds? To bed the Minister's wife? Steal his cabbages? Why does Qin not trust us with that information?"

"If this is some sort of tamzing," Shan said impassively, "there should be witnesses. There are rules."

Tan's head did not move, but his eyes shot up, transfixing Shan. "The conduct of struggle sessions is not one of my responsibilities," he said acidly, and considered Shan in silence for a moment. "The day you arrived, Zhong sent your folder to me. I think it scared him. He watches you."

Tan gestured to a second folder, an inch thick. "Started his own file. Sends me reports on you. I didn't ask, he just started sending them. Results of tamzing sessions. Reports of work output. Why bother? I asked him. You're a phantom. You belong to Qin."

Shan gazed at the two folders, one with a single yellowed sheet, the other crammed with angry notes from an embittered jailkeeper. His life before. His life after.

Tan drank deeply from his teacup. "But then you asked to celebrate the chairman's birthday." He opened the second folder and read the top page. "Most creative." He leaned back and watched the smoke wisping toward the ceiling. "Did you know that twenty-four hours after your banner we had handbills circulating in the marketplace? In another day an anonymous petition appeared on my desk, with copies being passed around the streets. We had no choice. You gave us no choice."

Shan sighed and looked up. The mystery was over. Tan had decided he had not been punished sufficiently for his role in Lokesh's release. "He had been imprisoned for thirty-five years." Shan's voice was little more than a whisper. "On holidays," he said, not knowing why he felt the need to explain, "his wife would come and sit outside." He decided to address Mao. "Not allowed closer than fifty feet," he said to the photograph. "Too far to talk, so they waved to each other. For hours they just waved."

A narrow smile, as thin as a blade, appeared on Tan's face. "You have balls, Comrade Prisoner Shan." The colonel was mocking him. A prisoner did not deserve so hallowed a title as Comrade. "It was very clever. A letter would have been a disciplinary offense. If you had tried to shout it out you would have been beaten into silence. Your own petition would have been burned."

He inhaled deeply on his cigarette. "Still, you made Warden Zhong look like a fool. He will always hate you for it. He asked for your transfer out of the brigade. Said you were a saboteur of socialist relations. Couldn't guarantee your safety. The guards were furious. An accident could happen to Minister Qin's special guest. I said no. No transfer. No accident."

Shan looked into Tan's eyes for the first time. Lhadrung was a gulag county, and in the gulag, prison wardens always had their way.

"It was his embarrassment, not mine. Releasing the old man was the right thing. Gave him a double ration book." Smoke drifted out of the colonel's mouth. He shrugged as he caught Shan's stare. "To correct the oversight."

Tan closed the folder. "Still, I grew curious about our mysterious guest. So political. So invisible. I wondered, should I worry about the next bomb you might throw our way?" He took another drag on his cigarette. "I made my own inquiries in Beijing. No more information, they said at first. Qin was not available. In the hospital. No more data on Qin's prisoner available."

Shan stiffened and looked back at the wall. The chairman seemed to be staring back now.

"But it was a quiet week. My curiosity was aroused. I persisted. I discovered that the memo in the file was prepared by the headquarters of the Public Security Bureau. Not the office in Xinjiang that arrested you. Not in Lhasa where your sentence was entered. Over nine hundred prisoners, only one has a file prepared by the Bureau's Beijing office. I think we never appreciated just how special you are."

Shan stared into Tan's eyes again. "There's an American saying," he said slowly. "Everyone is famous for fifteen minutes."

Tan froze. He cocked his head and continued to stare at Shan, as if he wasn't sure he had heard right. The knife-edge smile slowly reappeared.

There was a rustle of small feet behind Shan.

"Madame Ko," Tan said, the cold smile still on his face. "Our guest needs more tea."

The colonel was too old to be on the promotion lists, Shan decided. Even at his exalted level, a post in Tibet was a post in exile.

"I found more about this mysterious Comrade Shan," Tan continued, shifting into the third person. "He was a Model Worker in the Ministry of Economy. Commendations from the chairman for special contributions to the advancement of justice. He was offered Party membership, an extraordinary reward for someone halfway through his career. Then he did something even more extraordinary. He declined. A very complex man."

Shan sat. "We live in a complex world." He saw that his hands, unconsciously, had made a mudra. Diamond of the mind.

"Especially when you consider that his wife is a highly regarded Party member, a senior official in Chengdu. Former wife, I should say."

Shan looked up in alarm.

"You didn't know?" Tan asked with a satisfied smile. "Divorced you two years ago. Annulled, actually. Never lived together, she said."

"We"– Shan's mouth was suddenly bone-dry-"we have a son."

Tan shrugged. "Like you said. It's a complex world."

Shan closed his eyes to fight the sudden pain in his gut. They had finished the final chapter in their rewriting of his life. They had managed to take away his son. It wasn't that they were close. Shan and his son had spent maybe forty days together in the fifteen years since the boy was born. But one of the prisoner's games he played was fantasizing about the relationship he might have someday with the boy, about somehow creating the sort of bond Shan had shared with his own father. He would lie awake, wondering where the boy might be, or what he would say when he met his father again. The imagined relationship had been one of Shan's last slender reeds of hope. He pressed his palms against his temples and leaned over in his chair.

When he opened his eyes Tan was staring at him with a pleased expression. "Your brigade found a body yesterday," he said abruptly.

"Lao gai prisoners," Shan said woodenly, "are acquainted with death." No doubt they had told the boy that Shan had died. But died how? As a hero? As a disgrace? As a slave used up in the gulag?

Tan opened his mouth and watched the smoke rise languidly to the ceiling. "Attrition in the work brigades is always to be expected. Finding a decapitated Western visitor is not."

Shan looked up, then turned away. He did not want to know. He did not want to ask. He stared into his cup. "You have confirmed his identity?"

"The sweater was cashmere," Tan said. "Nearly two hundred American dollars in his shirt pocket. A business card for an American medical equipment firm. He must have been an unauthorized Western visitor."

"His skin was dark. Black hair on the body. Could have been Asian, even Chinese."

"A Chinese of such a rank? He would have been missed. And there was the business card from an American company," Tan reported victoriously. "The only Westerners allowed in Lhadrung are those operating our foreign investment project. They are too conspicuous not to be missed. In two more weeks American tour groups will begin to visit. But none yet." Tan pulled on his cigarette one last time before crushing it out. "I am pleased to see your interest in the case."

Shan's eyes drifted past Tan to the slogan. Truth Is What the People Need. It could be read more than one way. "Case?" he asked.

"There will have to be an inquest. A formal report. I am also responsible for judicial administration in Lhadrung County."

Shan considered whether the statement was intended as a threat. "My squad did not make the discovery," he said tentatively. "If the prosecutor needs statements he should talk to the guards. They saw as much as we did. All I did was clear a few rocks." He shifted to the edge of his seat. Could he have been called in error?

"The prosecutor is on a month's leave in Dalian, on the coast."

"The wheels of justice are accustomed to moving slowly."

"Not this time. Not with American tourists on the way and an inspection team from the Ministry of Justice arriving the day before. Their first inspection in five years. An open death file could give the wrong impression."

A knot began to tie itself in Shan's gut. "The prosecutor must have assistants."

"There is no one else." Tan leaned back, studying Shan. "But you, Comrade Shan, were once the Inspector General of the Ministry of Economy."

There had been no mistake. Shan stood and moved to the window. The effort seemed to sap him of strength. He felt his knees shaking. "A long time ago," he said at last. "A different life."

"You were responsible for compiling the two biggest corruption cases Beijing has ever known. In your time you sent dozens of party officials to hard labor camps. Or worse. Apparently there are some who still revere your name, even those who fear it. Someone in your old ministry said it was obvious why you were in prison, because you were the last honest man in Beijing. Some say you went to the West and you're still there."

Shan stared out the window, seeing nothing. His hand was shaking.

"Some say you went, and the Bureau brought you back because you knew too much."

"I was never a prosecutor," Shan spoke toward the glass, his voice cracking. "I collected evidence."

"We're too far from Beijing to split such fine hairs. I was an engineer," Tan said to his back. "I commanded a missile base. Someone decided I was qualified to administer a county."

"I don't understand," Shan said hoarsely, leaning against the window, wondering if he could ever find strength again. "That was another life. I'm not the same man."

"Your entire career was spent as an investigator. Three years is not so long."

"Someone could be brought in."

"No. That might demonstrate a certain…" Tan searched for the words, "…lack of self-sufficiency."

"But my file," Shan protested. "I have been proven…" His words drifted away. He pressed his hands against the glass. He could break it and jump. If your soul was in perfect balance, Choje said, you would just float away to another world.

"Proven what? A thorn in Zhong's side? I grant you that." Tan opened the thick file and rifled through the papers. "I'd also say you have proven yourself shrewd. Methodical. Responsible, in your own way. And a survivor. For men like you, surviving is the supreme skill."

Shan did not have to ask what Tan meant. He stared into his callused bone-hard hands. "I have been warned against regression," he protested. "I am a road laborer. I am supposed to think in new ways. I build for the prosperity of the people." It was the last refuge of the weak. When in doubt, speak in slogans.

"If none of us had a past, political officers would have no work," Tan observed. "Failure to confront the past, that is the real sin. I want you to confront yours. Let the inspector live again. For a short while. I do not know the words the Ministry expects. I do not speak the language. No one here does. I want a file prepared that can be quickly closed. I am without the benefit of the prosecutor's thinking. It is not something I will discuss with him on the phone two thousand miles away. I need the matter framed in terms the Ministry of Justice understands. Terms that will not attract further scrutiny. I wager you still have the Beijing tongue."

Shan sank into the chair. "You can't do this."

"It's not much I'm asking," Tan said with false warmth. "Not a full investigation. A report to support the death certificate. Explaining the likely accident that led to such an unfortunate demise. It could be your opportunity for rehabilitation." Tan gestured toward Zhong's file. "You could use a friend."

"Must have been a meteorite," Shan muttered.

"Excellent! Precisely what I mean. With that kind of thinking we can wrap this up in a day or two. We will think of an appropriate reward. Say, extra rations. Light duties. Assignment to a repair shop, perhaps."

"I won't," Shan said in a very still voice. "I mean, I cannot."

Amusement lifted Tan's face. "On what grounds do you refuse, Comrade Prisoner?"

Shan did not reply. On the grounds that I cannot lie for you, he wanted to say. On the grounds that my soul has been worn to a few thin threads by people like you. On the grounds that the last time I tried to find the truth for someone like you I was sent to the gulag for my trouble.

"Perhaps you have been confused by my hospitality. I am a colonel in the People's Liberation Army. I am a party member of rank seventeen. This district belongs to me. I am responsible for educating the people, feeding the hungry, constructing civil works, removal of waste, custody of prisoners, supervision of cultural activities, movement of the public buses, storage of communal food. And eradication of pests. Of any variety. Do you understand me?"

"It is impossible."

Tan slowly drained his tea and shrugged. "Still, you are not permitted to refuse."