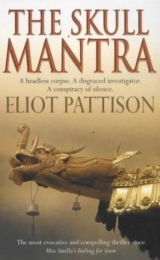

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"You think I want a massacre?" Tan's face clouded. "Forty years in the army and that's how I will be remembered. For the massacre at the 404th."

The limousine honked its horn. Tan sighed. "Li Aidang wants me to follow. We must go. I will drop you at Jade Spring. There is a reception for the American tourists. Then final planning for the Ministry delegation. A special banquet. Comrade Li apparently expects to be installed as prosecutor after the trial."

They stopped above the turnoff to Jade Spring Camp. Two soldiers manned a new barricade across the road, restricting access to the prison and the base. On it was a sign, in English only. It said ROAD CLOSED FOR REPAIRS. Shan puzzled over it, then remembered. The American tourists.

Before Shan climbed out of the car Li appeared at the window and dropped an envelope onto Tan's lap.

"I have completed my report and the murderer's statement," he announced. "The trial is set for the day after tomorrow, ten in the morning. At the People's Stadium." He looked at Shan with a new chill in his eyes. "Ninety minutes have been scheduled. It must not interfere with lunch."

The top page in the file was a handwritten list of names. Shan pulled it out for closer inspection. Honored guests for the event at the stadium, to be seated on the stage. Members of the visiting Ministry of Justice delegation topped the list, followed by Colonel Tan and half a dozen local officials. Shan saw Director Hu of the Ministry of Geology listed, and Major Yang of the Public Security Bureau. A shiver moved down his spine as he saw an ideogram near the bottom. No name, no title, just the inverted Y with the two bars.

As Shan pointed to the mark, Tan saw the question in his eyes. "Just the nickname," he said with disgust. "He likes his friends to use it. Thinks it's funny."

"Sky?"

"Not sky. Heaven. You know, god in heaven. All the priests pay homage to him."

Shan lifted the paper and stared at it with grim determination. The other guest on the podium was the man who had signed the confirmation on the index card bearing Jao's chop he had taken from the museum, and the same man who had signed the note to Prosecutor Jao, the note that Shan believed, but could not prove, had lured Jao to his death.

Wen Li, Director of Religious Affairs.

Chapter Eighteen

Sungpo was moving for the first time. He held the old man's head in his lap, wiping it with a wet rag, sometimes pausing to drop rice into his mouth, one kernel at a time.

"We tried to get a doctor," Shan said. He felt helpless. "A town doctor." But Dr. Sung had refused. When he had called to beg her to change her mind she had offered an abundance of excuses. She had clinic hours, she said. She had surgery, she said. She wasn't authorized for a military base, she said.

"They told you, didn't they?" he had said to her. "That it was an old lama."

"Why would that make a difference?"

"Because of what happened at the Buddhist school."

In the silence that had followed, Shan wasn't sure if she was still on the line. "An old man is dying," he had pleaded. "If he dies we will have no way to speak to Sungpo. If he dies it may mean another will be wrongly executed. And a murderer will go unpunished."

"I have a surgery," Dr. Sung had said, almost in a whisper.

"Don't give me excuses," Shan had replied. "Just tell me you don't want to." She did not respond. "I realized something the other day in your office," he pressed. "You're not bitter about the world, like you want everyone to think. You're just bitter about yourself."

The line had gone dead.

"Rinpoche," Shan said softly. "I could get tsampa. Tell me what you need to eat." He felt the old man's pulse. It was slow and faint, like the occasional rustle of a feather.

Je's eyes flickered open. "I am not in need," he said with a strength that belied his appearance. "I am looking for a gate. I found doors, but they are locked. I am looking for my door."

"It's only another day. We will have you home after tomorrow."

Je said something, so softly Shan could not hear. It was for Sungpo, who understood, and guided Je's hand to the rosary on his belt. Je began a mantra.

Jigme had been allowed to enter the guardhouse, at Shan's insistence. He had instantly retreated to the darkest corner of the cell. When he returned the rice cup was empty. Shan moved toward the corner. For a moment Jigme blocked his way, looking back and forth from Sungpo, to Je, then relented.

He had constructed a tiny spirit shrine by pushing two headrest stones against the wall and stacking a third on top. Between the bottom stones were half a dozen balls of rice, the pliers from the desk and the wire. They rested on several small bright white papers.

Shan reached to touch the papers and Jigme slapped his hand away.

"The guard, he had them at the desk when I came. Laughed and showed them to Sungpo. Sungpo meditated. The guard threw them into the cell. I gathered them before anyone could see. I must burn them. They are disrespectful."

They weren't papers, Shan saw as he turned them over. They were photographs. They were a dozen photographs, of three different monks with Public Security officials. With a wrenching chill Shan recognized the monks from the pictures in Jao's files. Each of the first three members of the Lhadrung Five was the subject of a series of four frames. First, standing between two officers at his trial. Kneeling on the ground. Then a pistol held eighteen inches behind his skull. Finally, sprawled on the ground, dead, his head at the center of a pool of blood.

With shaking hands, Shan stacked the photos and put them in his pocket.

Sungpo was speaking to Je again. A hoarse wheezing laugh came from the old man. "He says to tell someone we'll need to begin soon," Je explained. Begin? Then Shan understood. Begin the rites for passage of his soul. The old man's eyes wandered toward the cell door and lingered uncertainly upon the figure of Yeshe, then moved languidly on. "When you let it drift sometimes it finds its own way," he murmured, as if a thought had inadvertently found its way to his tongue.

Jigme was at the bars, holding on as though he might otherwise be carried away. "We could ask him to come down from the mountain," he whispered to Shan. "For such a holy man, maybe he would help."

"A healer?" Yeshe asked. "Did you find a healer?"

"He's hungry, that horse-headed one," Jigme said with a hollow tone. "Okay, let him eat me. I don't care. Maybe then you can talk with him, maybe then he'll help you save Sungpo."

Instantly Shan was at his side, pulling him from the bars. "You found him? You found Tamdin?"

There was a cave, Jigme finally confessed, where the demon slept. "The hand of the demon was gone, but the old man we brought from the market knew the prayers well. Only villagers and herders came at first. But then one came from above, stepping down the mountain like a goat, on a path no wider than a man's hand. He had left the prayer against dogbite, recited a few mantras, and climbed back up the slope. Even without the old man I would have known it was Tamdin's servant. Because of them."

"Them?"

"The vultures. They followed like they were tame, as if they knew he would provide fresh meat for them."

Jigme and Sergeant Feng had followed Tamdin's servant up the treacherous path for over a mile up the slope, into a blind gorge near the top. "When he left with an empty water jug I went in. But Tamdin was in wolf demon form." Jigme pulled up his pant leg to show a jagged, weeping wound on his calf, outlined by a row of punctures. "Hot damn, I run like hell."

"You could find him again?" Yeshe asked excitedly.

Jigme nodded slowly, looking at Je. "Let him eat me, as an offering. I don't care. Sungpo will find me in the next life. Fill his belly, then maybe Tamdin will speak with you. You ask him to come down to the valley, for Rinpoche. But there may not be time. Up that mountain, it is far above the American's shrine. Hard climb."

"No," Shan interjected. "There is an easier way."

"How could you know?" Yeshe asked.

"Because I know where Tamdin's servant came from."

***

The four men moved over the rocks silently, lost in thought and fear, the wind deviling them, the high altitude sapping their strength. They had found the path where Shan had expected, parallel to the Dragon's Throat, intersecting the road behind the rock formations near the old suspension bridge. It rose precipitously up the North Claw for nearly a mile, then struck a course along the crest of the long ridge.

Jigme, who had insisted on the lead, suddenly dropped to his knees and pointed ahead on the path. "Him!" he gasped. "The servant!"

Feng's hand slipped to his holster. "No," Shan said. "He will do us no harm. Let me speak to him alone."

Shan was sitting alone in a group of boulders, the others hidden on the far side, when the man approached. He was carrying a canvas sack over his shoulder and wore two gau around his neck. He stopped abruptly and squinted at Shan.

"Hello, Chinese."

"I am glad it is you, Merak."

The ragyapa headman nodded as if he understood. "There never was anyone else asking for the charms, was there?" Shan asked.

Merak set the bag down and leaned against the rock beside Shan, his hand on his gau. He seemed relieved to have been discovered. "But who would have believed it? It's not often a ragyapa is able to do great things."

"What is it you do for him?"

"A demon needs much rest. He must be protected while he rests. I was afraid that if I could find him, others might, too."

"How long has it been?"

"That bastard Xong De. Director of Mines. He refused to let my nephew work in the American mine."

"Luntok," Shan said with sudden understanding. "Your nephew is Luntok? The one who climbs mountains."

"Yes," Merak said with obvious pride. "He is going to climb Chomolungma, you know."

"But how did he get his job if he was rejected?"

"Xong died. People say Tamdin did it. I believed it, because afterward Tibetans were given jobs at the mine. Permission for Luntok was quickly granted. I wanted to offer tribute to Tamdin. I knew he lived in the high mountains. I kept watching. Then, when Luntok found his hand I knew where to look. I know our vultures. They seek their food on the high ridges. That bird dropped the hand near the Americans. After he picked it up he would quickly realize it was not his usual food. He would have dropped it soon after finding it."

"Which meant Tamdin was in a high cave near the Americans."

Merak nodded vigorously. "At first I was afraid I had disturbed him. I touched his golden skin. But when I felt his power I realized what I had done, and ran away."

"But you went back with charms of forgiveness. And you have been helping ever since."

"He was hurt bad, I could see that. Lost his hand fighting that last devil. So many battles he has had. I returned his hand, and brought the charms, but I knew he needed rest. I brought them there, to protect him while he recovered from his wounds. I have been taking food and water ever since."

"Food and water?"

"I know the difference between demons and creatures of flesh and blood."

"Why would you need prayers to protect you from them, if they are yours?"

"Not mine. I bought them from a herder. Now they belong to Tamdin."

Shan studied him with a vague but rising sense of dread. "Do you wish to come with me?"

Merak picked up his bag and shook his head heavily. "I know you have to do this, Chinese. People tell about how you did the summoning. You cannot turn back."

Pointing down the path Merak explained to Shan how the entrance was hidden from view, half a mile away inside a small gorge, then shook his head again before leaving. "I don't want to be there when a Chinese tries to enter. You should wish to come with me. I liked you."

When they found the gorge Shan studied his companions. "Sergeant," he said, with a gesture toward Jigme. "His leg is bleeding again. You need to bandage it." Shan ripped off the tail of his shirt and handed it to Feng.

Sergeant Feng, staring nervously into the gorge, seemed not to hear at first. Then he turned and frowned. "You think I'm scared of the demon?"

"No. I think his leg is bleeding."

Feng grunted, and guided Jigme to a flat rock at the mouth of the gorge. Shan and Yeshe followed the gorge as it narrowed into a small passage, then abruptly opened into a clearing.

The instant Shan stepped into it, the beasts attacked.

The creatures were eating the food left by Merak, but instantly sprang up at the sight of Shan, teeth bared, growling viciously. They were the biggest dogs he had ever seen, black Tibetan mastiffs, bred to defend the herds against wolves and leopards, but much larger than the dogs Shan had seen in Kham. If they had not been tied they would have torn him apart. When Rebecca Fowler had conducted the ceremony at the foot of the mountain, something had howled in the night.

Beyond the dogs was the cave.

Suddenly, like a cold whisper over his shoulder, he remembered the words of Khorda's fortuneteller. Bow before black dogs, she had warned. He dropped to his knees, then prostrated himself. The dogs quieted, curious. There was movement beside him. Yeshe was there, speaking in a low, comforting tone, holding his rosary for the animals to see. Incredibly, the dogs lowered their heads and slowly moved forward. Yeshe began to stroke them, reciting a prayer. Shan thought of Khartok gompa again. The dogs were the incarnations of failed priests.

Inside, there were torches leaning against a rock. Shan lit one and followed the tunnel as it curved to the right and opened into a large chamber. He froze, for an instant seized with panic. His heart stopped beating. It was looking at him. It was coming toward him, baring its red fangs. He had violated its holy ground and it would take his head, too.

"No!" he called out and shook his head violently, as though to release himself from the spell. He told himself it was a trick of the light and, battling his fear, moved forward. The headdress and costume had been deliberately arranged on a wooden frame to frighten intruders. Its finely worked gold gleamed, and the necklace of skulls danced in the flickering flame. Khorda's summoning spell had worked, he mused darkly. But who was summoning whom? Tamdin seemed to be waiting for him.

There were words Choje would want him to say, but he could not recall them. There were mudras he could make in offering, but his fingers seemed paralyzed.

He did not know how long he stood, hypnotized by the creature he had hunted. Finally he jammed the torch between two rocks and moved slowly around the costume, in awe of its power and beauty. On the front, rows of disk-shaped emblems had been sewn. He pulled the disk found by Jilin from his pocket. Just below the waist there was a gap where the disk fit perfectly.

A shudder came from behind him. Yeshe had entered, and was feeling the power of the demon. He dropped to his knees and offered a prayer.

Behind the costume was a flat, tablelike rock which held Tamdin's ritual instruments. The nearest was a large, curved flaying blade with a handle on top. He touched the blade; it was razor-sharp, certainly sharp enough to sever a human head. Special boots over which were mounted gold-plated shin plates stood under the rock. The arms were arrayed on another rock near the wall, one mangled and missing a hand. Merak had reverently placed the broken hand below it.

Shan touched his gau. Oddly, it seemed hot. He slipped a trembling hand into the worn leather sleeve of the functioning arm. It was fitted with elaborate levers and pulleys. He pushed a lever near the wrist and a line of tiny skulls along the upper arm turned. He pushed another and claws extended from the fingers. Another set of arms, small false limbs mounted near the shoulder of the real ones, could be manipulated with rings that fit over the fingers of the dancer. It was a wondrous machine, a vast technical feat even in modern times. Certainly it would take hours to learn to use it. But not weeks, not months. The months of training for the Tamdin dancers, Shan realized, must have been for the ceremonial motions, for the coordination of the machine with the complex rituals for which it had been designed.

Shan pulled Tamdin's arm snugly to his shoulder. It felt surprisingly comfortable, almost natural. The silk lining allowed almost unfettered movement. He extended the claws and found himself staring at them with a feeling of immense power. He worked them in and out. This was Tamdin. This was the way one became Tamdin.

A feeling of great satisfaction began to swell within him. With this arm, with these claws, with this power, accounts could be settled.

A startled gasp from behind him pushed the spell back. Yeshe leapt forward and began to pull the thing from Shan's arm. Then suddenly Shan, too, felt the darkness and ripped it from his body. The two men stood over it, then in unison looked up. The two black dogs were sitting at the mouth of the cave, staring at Shan with a silent but chilling intensity.

His hand shaking, Shan pointed to three large rosewood boxes in the shadows. They quickly discovered that the boxes had been designed to transport the costume, one fitted with a post for the headdress. There was an envelope fastened inside the chest with yellowed tape. From it Yeshe pulled several pages of paper, some brittle with age.

The top pages were the missing audit report from Saskya gompa, completed fourteen months earlier and recording the discovery of the boxes in the quarters of an old lama who had once been the Tamdin dancer.

"But who took it?" Yeshe asked. "Who stole the costume and brought it here? Director Wen?"

"I think Wen knew, but it is only part of the puzzle. Wen didn't use the costume. Wen didn't take the prosecutor's head to the shrine." He didn't believe enough, is what Shan meant. Whoever had used the costume and severed Jao's head was a zealot.

"You mean you think now a monk did steal it?"

"I don't know," Shan said, feeling his frustration rise like a great lump in his chest. He had expected the end of his long search for Tamdin would have brought him the answers he needed. "Maybe only the lama they took it from knows."

Yeshe turned to the older pages. "A report," he announced after scanning the first page. "An anthropologist from Guangzhou. History of the costume. Details of the ceremony, as he witnessed it in 1958." He paused and looked up. "At Saskya gompa. Saskya was the only gompa in the county to perform the dance." He began reading out loud. "The knowledge of the ceremony was a sacred trust," he read, "passed from a single monk in one generation to one in the next. The Tamdin dancer in 1958 was considered the best in all of Tibet."

"But who," Shan thought out loud, "had the costume last year? The old dancer, if he were still alive. Or his student. He would know who took it. That's the proof we need. That's the link to the murder."

Yeshe read on silently for a few more paragraphs, then lowered the papers and stared at Shan in confusion. Shan pulled the page from his hand and read it. The dancer in 1958 was Je Rinpoche.

***

A tent had materialized in front of the barracks, a yurt-style structure of yak-hair felt. Four monks were quietly waiting at the gate. Feng pulled the truck to a stop as they watched.

Four knobs approached the gate, carrying a litter. The gate opened, and the monks took the litter, walking in tiny, painstaking steps, wary of their fragile burden. The tent flap opened and they were admitted. An ancient truck, its engine sputtering loudly, approached, brakes screeching, and parked beside the tent. Shan recognized some of the men who climbed out. Monks from Saskya gompa.

Inside, the tent was hazy with the smoke of incense. The old priest Shan had met in the temple at Saskya was bent over Je, washing Je for the ceremony. A second older monk with a brocaded sleeve– he must be the kenpo of Saskya, Shan realized– presided at the head of the litter, which was raised on bales of straw. As Shan and Yeshe approached, two younger priests stepped before them. Yeshe pushed forward, as though to protect Shan.

"We must speak with him," Shan protested.

They did not speak, but pointed to a space beside a group of monks who sat before the pallet, spinning prayer wheels and softly reciting mantras.

"One question," Yeshe said urgently. "Rinpoche would not begrudge one question."

The priest glared at Yeshe. "Where did you study?"

"Khartok gompa. I can explain," Yeshe pleaded. "It is about saving Sungpo. Maybe even saving the 404th."

The priest looked at Shan. "The Bardo ceremony has been started. The transition has already begun. His soul. Already it is lifting out. It requires all his concentration. He can see a small light now, in the far distance. If he breaks away, if he loses it for an instant he could be sent somewhere that was not intended. He may never find it. He may drift endlessly. This monk from Khartok knows that," he said with a scornful glance at Yeshe.

They sat and waited. Yeshe began saying his rosary, but as Shan watched he slowly lost count and began twisting his fingers, turning the knuckles white. Butter lamps were brought in and lit.

"You don't understand!" Yeshe suddenly blurted. "He could save Sungpo! We can protect the 404th!"

The kenpo turned and stared icily. One of the younger monks angrily stepped toward Yeshe as though to physically restrain him, but was interrupted by a sudden stirring at the door. Low, urgent protests could be heard. The flap was thrown open and Dr. Sung appeared. She glared at Shan and ignored everyone else, then stepped to the pallet. The moment she opened her bag the abbot called out and clamped his hand over her arm.

She did not speak. Their eyes locked. With her free hand she pulled a stethoscope from the bag, slung it around her neck and then, one finger at a time, peeled away the abbot's hand. He did not move but did not stop her examination.

"His heart isn't beating enough to keep a child alive," she said. "I suspect a blockage."

"Is it treatable?" Shan asked.

"Perhaps. But not here. Need to run tests at the clinic."

"Just one question," Yeshe pressed, looking at his watch. "We need to know. He is the only one who can tell us."

Sung shrugged and filled a syringe with a clear fluid. "This will wake him," she said. "At least briefly." She scrubbed Je's arm.

As she bent with needle the abbot placed his hand over the prepared patch of skin. "You have no idea of what you are doing," he said.

"He's an old man in need of help," Yeshe pleaded. "He doesn't have to die here. If he dies now, Sungpo may die, too."

"His entire life was dedicated to this moment of transition," the abbot warned. "It cannot be stopped. He has already begun to cross over. He is in a place none of us are allowed to disturb."

Dr. Sung looked at the priest as if for the first time, then slowly lowered the syringe and looked to Shan, who moved to the platform. "You're the one who asked me," she said. But her confused tone made it sound more like a question than an accusation.

"If he dies today, Sungpo will die tomorrow," Yeshe said in a desolate voice over Shan's shoulder. "It will all be for nothing. If we don't have the answer now, we will never have it."

Shan gestured toward the entrance. The doctor dropped her instruments on the pallet and followed him.

"If it is sickness we should take him back," Shan said quietly. "If it is just a natural passing-"

"What do you mean, natural?" Dr. Sung asked.

Shan looked outside, past the barbed wire to the long building where Sungpo sat. "I guess I don't know anymore."

"If I could do tests," Sung suggested, "maybe we could-"

She was interrupted by a horrified shout. They spun about. The priests were jumping to their feet. The old abbot was flogging Yeshe on the head with a ritual bell.

Yeshe stood over the pallet with tears running down his face. He had injected the syringe into Je.

Everyone was shouting. Someone demanded to know the name of Yeshe's abbot. Someone grabbed his red shirt and ripped it off his back. They were abruptly silenced by the rising of Je's arm.

The arm extended vertically, the hand rotating in a slow eerie motion, as if clutching for something just beyond its grasp.

Shan darted to Je's side and wiped his forehead with the wet rag. The old man's eyes fluttered opened and he stared at the felt roof above him. He brought the extended hand down to his face and studied it, moving the fingers with exquisite slowness, like that of a butterfly in the cold. He turned and put his fingers on Shan's face, squinting as if he could not see it well. "Which level is it, then?" he whispered in a dry croaking voice.

"Rinpoche," Yeshe said urgently. "You were the Tamdin dancer at Saskya. You kept the costume until last year. Who took it from you?" he pleaded. "Did you teach it to them? Who was it? We must learn who took the costume."

Je gave a hoarse laugh. "I knew people like you in the other place," he said with a rasping breath.

"Rinpoche. Please. Who was it?"

His eyes flickered and shut. There was a new sound, a rattle in his chest. They watched in agonized silence for several minutes.

Then the eyes opened again, very wide. "In the end," he said slowly, as though listening for something, each word punctuated by the wheezing rattle, "all it takes is one perfect sound." He closed his eyes and the rattle stopped.

"He's dead," Dr. Sung announced.