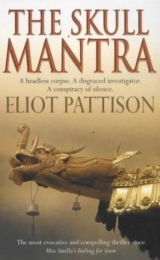

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Chapter Two

Shan sat silently in the cold, dim room they assigned him in the prison administration building at the 404th, staring at the telephone. At first he was convinced it wasn't real. He tapped it with a pencil, half expecting it to be made of wood. He pushed it, wondering if the wire would drop off. It was a thing of the past, of another world, like radios and televisions, taxis and flush toilets. Artifacts from a life he had left behind.

He stood and paced around the table. It was a storage room without windows, the room where small groups met for struggle sessions, the tamzing where antisocialist spasms were diagnosed and treated. Ammonia wafted from cleaning supplies stacked in one corner. A small notepad sat beside the phone, plus three pencil stubs pocked with toothmarks. Feng sat in a chair at the door, peeling an apple. His smug face did little to alleviate Shan's suspicion that he had been led into an elaborate trap.

Shan returned to the table and picked up the phone receiver. There was a dial tone. He dropped it back on its cradle, pressing his hand against it as though to restrain it. To what end was the trap? A trap for Shan? If, after so long, neither Beijing nor Shan would tell them what his crime was, then perhaps they had decided to create one they could better understand. Or was it for Choje and the monks? Who did they expect him to call? Minister Qin? His party functionary wife who had erased their relationship? The son whose face he would not recognize even if he ever saw him again?

He picked it up again and dialed five random digits.

"Wei," a woman said impassively, with the ubiquitous, meaningless syllable used by everyone to answer phones. He hung up and stared at the telephone. He unscrewed the mouthpiece and found, as expected, an interceptor microphone, standard Public Security issue. Such devices had also been part of his prior incarnation. It could be active or inactive. It could be for him, or standard issue for all prison phones.

He replaced the mouthpiece and surveyed the room again. Every object seemed to have an added dimension, a heightened reality, as to a dying man. He turned to the pad, marveling at the clean, bright paper. Such brightness was not a part of the universe he entered three years earlier. The first page held a list of names and numbers, the rest were blank. With a slight tremble he turned the empty pages, pausing over each one as though reading a book. On the last page, in a top corner where it was least likely to be discovered, he made the two bold strokes that comprised the ideogram for his name. It was the first time he had written it since his arrest. He looked at it with an unfamiliar satisfaction. He was still alive.

Below his name he made the ideograms for his father's name then, with a pang of guilt, abruptly closed the pad and looked to see if Feng was watching.

From somewhere came a low moan. It could have been the wind. It could have been someone in the stable. He moved the pad away and discovered a folded sheet of paper under it. It was a printed form with the heading REPORT ON ACCIDENTAL DEATH.

He picked up the phone and dialed the first name on the list. It was the clinic in town, the county hospital.

"Wei."

"Dr. Sung," he read.

"Off duty." The line went dead.

Suddenly he realized someone was standing in front of his desk. The man was Tibetan, though unusually tall. He was young, and wore the green uniform of the camp staff.

"I have been assigned to you, to help with your report," the man said awkwardly, glancing about the room. "Where's the computer?"

Shan lowered the phone. "You're a soldier?" There were indeed Tibetans in the People's Liberation Army but seldom were they stationed in Tibet.

"I am not-" the man began with a resentful flash, then caught himself. Shan recognized the reaction. The man did not understand who Shan was, and so could not decide where he belonged in the strata of prison life or the even more complex hierarchy of China's classless society. "I have just completed two years of reeducation," he reported stiffly. "Warden Zhong was kind enough to issue me clothing on my release."

"Reeducation for what?" Shan asked.

"My name is Yeshe."

"But you are still in the camp."

"Jobs are few. They asked me to stay. I have finished my term," he said insistently.

Shan began to recognize an undertone, a quiet discipline in the voice. "You studied in the mountains?" he asked.

The resentment returned. "I was entrusted by the people with study at the university in Chengdu."

"I meant a gompa."

Yeshe did not reply. He walked around the room, stopped at the rear and arranged the chairs in a semicircle, as if a tamzing were to be convened.

"Why would you stay?" Shan asked.

"Last year they were sent new computers. No one on the staff was trained for them."

"Your reeducation consisted of operating the prison computers?"

The tall Tibetan frowned. "My reeducation consisted of hauling night soil from the prison latrines to the fields," he said, awkwardly trying to sound proud of his work, the way he would have been taught by the political officers. "But they discovered I had computer training. I began to help with office administration as part of my rehabilitation. Looking at accounts. Rendering reports to Beijing's computer formats. On my release, they asked me to stay for a few more weeks."

"So as a former monk your rehabilitation consists of helping imprison other monks?"

"I'm sorry?"

"It's just that I never cease to be amazed at what can be accomplished in the name of virtue."

Yeshe winced in confusion.

"Never mind. What kind of reports?"

Yeshe continued pacing, his restless eyes moving from Sergeant Feng at the door back to Shan. "Last week, reports on inventory of medicines. The week before, trends in the prisoners' consumption of grain per mile of road constructed. Weather conditions. Survival rates. And we've been trying to account for lost military supplies."

"They didn't tell you why I am here?"

"You are writing a report."

"The body of a man was found at the Dragon Claws worksite. A file must be prepared for the Ministry."

Yeshe leaned against the wall. "Not a prisoner, you mean."

The question didn't need an answer.

Yeshe suddenly noticed Shan's shirt. He stooped and looked under the table at Shan's battered cardboard and vinyl shoes, then back at Feng.

"They didn't tell you," Shan said. It was a statement, not a question.

"But you're not Tibetan."

"You're not Chinese," Shan shot back.

Yeshe backed away from Shan. "There was a mistake," he whispered, and moved to Sergeant Feng with his hands outstretched, as though beseeching his mercy.

Feng's only answer was to point toward the warden's office. Yeshe retreated with mincing steps and sat in front of Shan. He absently stared at Shan's shoes again then, apparently marshalling his strength, looked up. "Are you to be accused?" he asked, unable to hide the alarm in his voice.

"In what sense of the word?" Shan marveled at how reasonable the question sounded.

Yeshe stared at him wide-eyed, as if he had stumbled upon some new form of demon. "In the sense of a trial for murder."

Shan looked into his hands and absently picked at one of the thick calluses. "I don't know. Is that what they told you?" Perhaps that had been the plan all along. The old ones, like Tan and Minister Qin, enjoyed playing with their food before eating.

"They told me nothing," Yeshe said bitterly.

"The prosecutor is away," Shan said, struggling to keep his voice calm. "Colonel Tan needs a report. It is something I used to do."

"Murder?" Yeshe's voice sounded almost hopeful.

"No. Case files." Shan pushed the list toward Yeshe. "I tried the first name. The doctor was not available."

Yeshe looked back toward Sergeant Feng, then sighed as the sergeant refused to acknowledge his stare. "This is only for the afternoon," Yeshe said tentatively.

"I did not ask for you. You said it was your job. You get paid to compile information." Shan was confused at Yeshe's hesitation. He thought he had understood the reason for his new assistant. If the Bureau was watching, it would not rely simply on one bug in a phone.

"We are warned against collusion with prisoners. I am looking for a better job. Working with a criminal, I don't know. It could be seen as-" Yeshe paused.

"Regression?" Shan suggested.

"Exactly," Yeshe said, with a hint of gratitude.

Shan studied him for a moment, then opened the pad and began writing. Before this date I have never met the clerical assistant named Yeshe of the Central Prison Office of Lhadrung County. I am acting on the direct orders of Colonel Tan of the Lhadrung County government. He paused, then added: I am deeply impressed by Yeshe's commitment to socialist reform. He signed and dated the note, then handed it to the nervous Tibetan, who solemnly read it and folded it for his pocket.

"Only for today," Yeshe said, as if reassuring himself. "I just get assignments for a day at a time."

"No doubt Warden Zhong would not want such a valuable resource to be wasted for more than a few hours."

Yeshe hesitated, as if confused by Shan's sarcasm, then shrugged and retrieved the list. "The doctor," he said, suddenly all business. "Don't ask for the doctor. Call the office of the director of the clinic. Say Colonel Tan needs the medical report. The director has a fax machine. Tell them to fax it immediately. Not to you. The warden's secretary. The warden left. I will talk to her."

"He left?"

"Picked up by a driver for the Ministry of Geology."

Suddenly Shan remembered seeing the unfamiliar truck when the body had been found. "Why would the Ministry of Geology visit the 404th work site?" he wondered out loud.

"It's on a mountain," Yeshe replied stiffly.

"Yes?"

"The Ministry regulates mountains," Yeshe said distractedly, reviewing the list of names. "Lieutenant Chang. His desk is down the hall. The army ambulance crew who took custody of the body from the guards. Their records will be at Jade Spring Camp," he said.

"I will need an official weather report from two days ago," Shan said. "And a list of foreign tour groups cleared for entry into Tibet during the past month. China Travel Service in Lhasa should have it. And tell the sergeant we may be going back to town."

Five minutes later Yeshe began delivering the reports, still warm from the machine. Shan read them quickly, and began to write. He had nearly finished when a claxon sounded in the corridor, a siren he had heard only once before in all his months at the 404th. It was the signal for rifles to be issued to the prison guards. A chill crept down his spine. Choje had begun his resistance.

***

Colonel Tan eyed Shan suspiciously as he stood with the report in front of Tan's desk an hour later, then grabbed the papers and read.

The building seemed nearly empty. No, not just empty, Shan considered, but deserted, abandoned, the way small mammals abandon their roosts when a predator at the top of the food chain moves in. The wind rattled the windows. Outside, a crow appeared, mobbed by small birds.

Colonel Tan looked up. "You've given me the ancillary reports. But the form is incomplete."

"You have all of the direct investigation facts. And such conclusions as are available. It is all I can do. You will need to make some decisions."

Tan folded his hands over the pages. "It has been a very long time since anyone mocked my authority. In fact, I don't recall it happening since I took over the county. Not since I was given the black chop."

Shan stared at the floor. The black chop was the authority to sign death warrants.

"I had hoped for more, Comrade. I expected you would want to do a thorough job. Take time to embrace the opportunity I offered to you."

"On consideration," Shan said, "it seemed that certain things should be said quickly."

Tan picked up the report and read. "At 1600 hours on the fifteenth a body was discovered. Five hundred feet above the Dragon Throat Bridge. The unidentified victim was dressed expensively, in cashmere and Western denim. Black body hair. Two surgical scars on his abdomen. No other identifying marks. The victim walked up a dangerous ridge at night and suffered a sudden trauma to the neck. No direct evidence of third party involvement. Since no missing person reports have been filed locally, victim was likely a stranger to the area, possibly of foreign origin. Attachments of the medical report and security officer incident report."

He turned the page. "Possible explanations accounting for the trauma. Scenario one. Victim stumbled on rocks in darkness, fell upon razor-edge quartz known to be geologically present in the area. Two. Fell onto tool left by the construction brigade. Three. Unacclimated to high mountain atmosphere, suffered sudden attack of altitude sickness, passed out and incurred injuries as described in one or two." Tan paused. "No meteorite? I liked the meteorite. A certain Buddhist flavor. Predestination from another world."

He folded his hands over the report. "You have failed to give me conclusions. You have failed to identify the victim. You have failed to give me a report I can sign."

"Identify the victim?"

"It is awkward to have strangers in the morgue. It could be misinterpreted as carelessness."

"But that is precisely why the Ministry should not trouble you. You cannot be blamed if his family is negligent."

"A tentative identification would attract less attention. If not a name, a hat."

"A hat?"

"A job. A home. At least a reason for being here. Madame Ko called the American company on the business card. They sell X-ray equipment. Let's say he sold X-ray equipment."

Shan looked into his hands. "There can be nothing but speculation."

"One's man speculation may become another's judgment."

Shan gazed over the shadows that were beginning to cover the slopes of the Dragon Claws. "If I gave it to you, the perfect scenario," he said slowly, hating himself more with every word, "one the Ministry would embrace, would you release me back to my unit?"

"This is not a negotiation." Colonel Tan considered, then shrugged. "I had no idea breaking rocks was so addictive. I would be pleased to return you to the warden, Comrade Prisoner."

"The man was a capitalist from Taiwan."

"Not an American?"

Shan returned Tan's gaze. "How do you think the Public Security Bureau will react at the mention of the word American?"

Tan raised his brow and nodded, conceding the point.

"Taiwanese," Shan said. "It will explain his money and clothing, even why he could travel without being noticed. Say a former Kuomintang soldier who had served here, had sentimental ties. Came to Lhasa with a tour group, broke away on his own and traveled to Lhadrung illegally. The government could not be responsible for the safety of such a person."

Tan contemplated Shan's words. "Such things could be verified."

Shan shook his head. "Two groups from Taiwan visited Lhasa over the last three weeks. The report from China Travel Service is attached. If you wait three days to check, the groups will all be home. Officially, nothing can be done to verify anything in Taiwan. It is well known by Public Security that such groups are often used for illegal purposes."

Tan offered one of his knife-edge smiles. "Perhaps I judged you too hastily."

"It will be sufficient to complete a file," Shan explained. "After the inspection team leaves, your prosecutor will know what to do." As he spoke, he recalled Tan had another reason to close the matter soon. Before referring to the inspection team, he had mentioned Americans, on their way for a visit.

"What will the prosecutor know to do?"

"Convert it to a murder investigation."

Tan pursed his lips together as if he had bitten something bitter. "Only a Taiwanese tourist, after all. We must guard against overreaction."

Shan looked up and spoke to the photograph of Mao. "I said it was the perfect scenario. Do not confuse it with the truth."

"Truth, Comrade?" Tan asked with an air of disbelief.

"In the end, you will still have a killer to find."

"That will be a matter for the prosecutor and myself to decide."

"Not necessarily."

Tan raised an eyebrow in question.

"You can complete a file sufficient to divert the matter for a few weeks. Maybe even send the file without all the signatures. It might sit on a desk for months before someone notices."

"And why would I be so negligent as to send the file without signatures?"

"Because eventually the accident report will have to be signed by the doctor who performed the autopsy."

"Dr. Sung," Tan said in a low, sour voice, as though to himself.

"The medical report was rather thorough. The doctor noticed the head was missing."

"What are you saying?"

"The doctor has other authorities to whom she reports. They do their own audits. Without the head, I doubt your accident report will be signed by the medical officer. Without the report, the Ministry will eventually examine the case and classify it as a murder."

Tan shrugged. "Eventually Prosecutor Jao will return."

"But meanwhile a killer is out there. Your prosecutor should be considering the implications."

"Implications?"

"Like how this man was killed by someone he knew."

Tan lit one of his American cigarettes. "You don't know that."

"The body was unmarked. No evidence of a struggle. He smoked a cigarette with someone. He walked up the mountain voluntarily. His shoes were clean."

"His shoes?"

"If he was dragged, they would have been scuffed. If he had been carried, he would not have picked up the fragments of rock that were found on his soles. It's in the autopsy report."

"So a thief found a rich tourist. Forced him to walk up at gunpoint."

"No. He wasn't robbed– a thief would not have overlooked two hundred American dollars. And he didn't drive to the South Claw on a whim, or at the request of someone he did not know."

"Someone he knew," Tan considered. "But that would make it local. No one is missing."

"Or someone who knew someone here. An old feud rekindled by a sudden visitor. A conspiracy unraveled. An opportunity for settling a score presented itself. Have you tried to contact him?"

"Who?"

"The prosecutor. One of the troubling questions I didn't write down is why the murderer waited until the prosecutor left town. Why now?"

"I told you. I don't want to speak about this on the phone."

"What if something else is planned for his absence? Before the inspection team arrives."

He had Tan's attention now. "I don't know. I don't even know if he's reached Dalian yet." Tan studied the ember of his cigarette. "What would you have me ask?"

"Ask him about pending cases. Was he putting pressure on someone."

"I don't see-"

"Prosecutors look under rocks. Sometimes they stir up a nest of snakes."

Tan blew a stream of smoke toward the ceiling. "Did you have a particular breed in mind?"

"Potential informers get killed. Partners in crime lose trust. Ask if he was compiling a corruption case."

The suggestion stopped Tan. He crushed his cigarette and walked to the window. Staring out the window for a moment, he absently picked up a pair of binoculars and raised them toward the eastern horizon. "On a clear day when the sun is right, you can see the new bridge at the bottom of the Dragon Throat. You know who built that? We did. My engineers, without any help from Lhasa."

Shan did not reply.

Tan set down the binoculars and lit another cigarette. "Why corruption?" he asked, still facing the window. Corruption was always a more important crime than murder. In the days of the dynasties, those who killed sometimes simply paid fines. Those who stole from the emperor always died by a thousand slices.

"The victim was well dressed," Shan observed. "Had more cash than most Tibetans earn in a year. Statistics are kept in Beijing. Cross-references between cases. Classified, of course. Murders typically are the result of one of two underlying forces. Passion. Or politics."

"Politics?"

"Beijing's way of saying corruption. Corruption always involves a struggle for power. Ask your prosecutor when you reach him. He will understand. Meanwhile, ask him for a recommendation."

"Recommendation?"

"A real investigator, to start the fieldwork now. I can finish the form, but the real investigation needs to start while the evidence is fresh."

Tan inhaled and held the smoke in his lungs before speaking again. "I'm beginning to understand you," he said, letting the smoke drift out. "You solve problems by creating a bigger one. I wager that has a lot to do with why you are in Tibet."

Shan did not answer.

"The head rolled off the cliff. We will find it. I'll send squads out tomorrow. We'll find it and I'll persuade Sung to sign the report."

Shan continued to stare at Tan in silence.

"You're saying if the head isn't found the Ministry will expect me to offer up a killer."

"Of course," Shan agreed. "But that will not be their primary concern. First you must offer up the antisocial act. Your responsibility is detailing the socialist context. Provide a context and the rest will follow."

"Context?"

"The Ministry will not care about the killer as such. Suspects are always available." Shan waited for a reaction. Tan did not even blink. "What they always seek," he continued, "is the political explanation. Murder investigation is an art form. The essential cause of violent crime is class struggle."

"You said passion. And corruption."

"That is the classified data. Private, for use by investigators. Now I am talking about the socialist dialectic. Prosecution of murder is usually a public phenomenon. You must be ready to explain the basis for prosecution here. There is always a political explanation. That will be the concern. That is the evidence you need."

"What are you saying?" Tan growled.

Shan looked at the photograph and spoke to Mao again. "Imagine a house in the country," he said slowly. "A body is found, stabbed to death. A bloody knife is found in the hands of a man asleep in the kitchen. He is arrested. Where does the investigation start?"

"The weapon. Match it to the wound."

"No. The closet. Always look for the closet. In the old days you would look for hidden books. Books in English. Western music. Today you look for the opposite. Old boots and threadbare clothes, hidden away with a book of the chairman's sayings. In case of a new resurgence of Party enforcement. Either way it shows reactionary doubts about socialist progress."

"Then you check the party's central files. Class background. Find out that the suspect previously required reeducation or that his grandfather was an oppressor in the merchant class. Maybe his uncle was a Stinking Ninth." Shan's father had been in the Stinking Ninth, the lowest rank on Mao's list of bad elements. Intellectuals. "Or maybe the murderer is a model worker. If so, look at the victim," he continued. He realized with a shudder that he was repeating words he had last spoken to a seminar in Beijing. "It's the socialist context that's important. Find the reactionary thread and build from there. A murder investigation is pointless unless it can become a parable for the people."

Tan paced in front of the window. "But to get this behind us, all I really need is a head."

Something icy seemed to touch Shan's spine. "Not just any head. The head."

Tan laughed without smiling. "A saboteur. Zhong warned me." He sat and studied Shan in silence. "Why do you want so badly to return to the 404th?"

"It is where I belong. There's going to be trouble. Because of the body. Maybe I can help."

Tan's eyes narrowed. "What trouble?"

"The jungpo," Shan said very quietly.

"Jungpo?"

"It translates as hungry ghost. A soul released by a violent action, unprepared for death. Unless death rites can be conducted on the mountain, the ghost will haunt the scene of the death. It will be angry. It will bring bad luck. The devout will not go near the place."

"What trouble?" Tan repeated sharply.

"The 404th will not work at such a site. It is unholy now. They are praying for the release of the spirit. Prayers for cleansing."

Anger was building in Tan's eyes. "No strike was reported."

"The warden would never tell you so soon. He will try to end it on his own. There will have been stoppages by the crews at the top first. There will have been accidents. Guns have been issued."

Tan abruptly moved to his door and called for Madame Ko to dial Warden Zhong's office. He took the call in the conference room, watching Shan through the open door.

His eyes flared when he returned. "A man broke a leg. A wagon of supplies fell off the cliff. The brigade refused to move after the noon break."

"The priests must be permitted to perform the ceremonies."

"Impossible," Tan snapped, and strode back to the window. He pulled the binoculars from the sill, futilely looking through the gathering grayness for the worksite on the distant slope. When he turned, the hardness was back in his eyes. "You have a context now. What did you call it? A reactionary thread."

"I don't understand."

"Smells like class struggle to me. Capitalist egoism. Cultists. Acting to relieve their revisionist friends."

"The 404th?" Shan said, horrified. "The 404th was not involved."

"But you have convinced me. Class struggle has once again impeded socialist progress. They are on strike."

Shan's heart lurched at the words. "Not a strike. It's just a religious matter."

Tan sneered. "When prisoners refuse to work, it is a strike. The Public Security Bureau will have to be notified. It's out of my hands."

Shan stared helplessly. A death in the mountains might be overlooked by the Ministry. But never a strike at a labor camp. Suddenly the stakes were far higher.

"You will compile a new file," Tan explained. "Tell me about class struggle. How the 404th caused this death as an excuse to halt their work. Something worthy of an inspector general. The kind that the Ministry will not challenge." He scrawled something on a sheet of onion-skin paper, then studied Shan for a moment. With a slow, ceremonial motion, he fixed his seal to the paper. "You are officially on detail to my office. I'll give you a truck and the warden's Tibetan clerk. Feng will watch. Permission to go to the clinic for interviews. If asked, you are on trusty duties."

Shan felt as if someone was rolling a massive rock onto his back. He found himself bending, frantically looking toward the Dragon Claws. "My report would be worthless," he murmured, the words nearly choking in his throat. He had rushed his work to return to the 404th, to help Choje. Now Tan wanted to use him to inflict greater punishment on the monks. "I have been proven untrustworthy."

"The report will be in my name."

Shan stared at a dim, vaguely familar ghost, his reflection in the window. It was happening. He was being reincarnated into a lower life form. "Then one of our names will be dishonored," he said in croaking whisper.