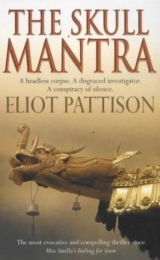

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

"He will not bless the protection charms? He does not want them protected from the jungpo?"

"Not the jungpo. These are for the evils of this world. Tsonsung charms. For protection from batons. From bayonets. From bullets."

Chapter Five

A sleek young man in a white shirt and a blue suit was waiting outside Tan's office the next morning. Pacing in front of the window, he paused to scornfully examine Sergeant Feng, then noticed Shan and threw him a knowing nod, as if they shared in some secret.

Shan moved to the window, desperate to discern activity on the slopes of the South Claw. The stranger mistook his movement for an invitation to converse.

"Three out of five," the man said. "Sixty percent request to go home before their tour is up. Did you know that, Comrade?" He had Beijing written all over him.

"Most of those I know serve their full terms," Shan said quietly. He leaned forward, touching the glass. The 404th should be on the slope by now. Would the warden even bother to take them out today?

"They can't take the cold," the man continued, giving no evidence he had heard Shan. "Can't take the air. Can't take the drought. Can't take the dust. Can't take the stares on the street. Can't take the two-legged locusts."

The stranger sprang to Madame Ko's side as she moved through the waiting room. "There is nothing more important!" he insisted, speaking slowly and loudly as if she were somehow incapacitated. "I must see him now!" She smiled coolly at him and pointed to the chairs along the wall.

But the man continued pacing, repeatedly glancing back at Tan's door. "I've been here two years. Love it. Could do ten. How about you?"

Shan looked up, slowly, hoping the man was not speaking to him. But his eyes were like two gun barrels, aimed directly at Shan. "Three so far."

"A man of my own heart!" the stranger exclaimed. "I love it here," he repeated. "The challenges of a lifetime. Opportunity at every crossroad," he said, looking at Shan for confirmation.

"At least surprise. Surprise at every crossroad," Shan offered judiciously.

The man replied with a short, restrained laugh and settled into the seat beside Shan. Shan covered his file with his hands.

"Haven't seen you before. Assigned to a unit in the mountains?"

"In the mountains," Shan grunted. The outer office was not heated, and he had not removed the anonymous gray coat Feng had found for him that morning in the back of the truck.

"Old man's got his bowl too full," the man confided, with a nod toward Tan's door. "Reports for the Party. Reports for the army. Reports for Public Security. Reports on the status of reports. We don't let bureaucracy interfere like that. No way to get things done."

Feng's head lurched backward. He began to snore.

"We?" Shan inquired.

With a theatrical air the man opened a small vinyl case and handed Shan an an embossed card.

Shan studied the card. It was made of paper-thin plastic. Li Aidang, it said. The name had been a favorite of ambitious parents a generation earlier. Li Who Loves the Party. Shan's gaze drifted to the title and froze. Assistant Prosecutor. Tan had done it, he thought, he had summoned an investigator from outside. Then he read the address on the card. Lhadrung County.

He rubbed his fingers over the words in disbelief. "You are very young for such a responsibility," Shan said at last, and studied Li. The assistant prosecutor could not have been much past thirty. He wore an expensive backdoor watch and, oddly, some kind of Western sporting shoes. "And a long way from home."

"Don't miss Beijing. Too many people. Not enough opportunity."

There was that word again. It was odd to hear an assistant prosecutor speak of opportunity.

Madame Ko reappeared.

"Obviously he doesn't understand-" Li began in a patronizing tone. "It's about the arrest. He needs to sign authorizations. He will want to inform the-"

Madame Ko moved out of the room without acknowledging Li. As Li stared after her a sneer grew on his face, as though he had made some mental note of particular delight. He leaned forward and studied Feng's slumped figure. "If this were my office, they'd show some respect," he began, his voice thick with contempt. Then Madame Ko emerged, opened the door to the adjoining conference room, and nodded for Li to enter.

Li gave a tiny snort of triumph and strode into the room. Madame Ko silently pulled out a chair for him at the table, then left him staring at the side door that opened into Tan's office, closing the door behind her as she reentered the waiting room.

"I wonder," Shan said, "if the colonel is planning to go in there." He wasn't sure she had heard as she moved into an alcove, but she answered with an amused nod as she returned with two cups of tea. She handed Shan one and sat beside him.

"He is a rude young man. There're so many like that today. Not raised well."

Shan almost laughed. It was how his father would have described the generations of Chinese raised since the middle of the century. Not raised well. "I wouldn't want him to be angry with you," Shan said.

Madame Ko gestured for him to drink his tea. She had the air of an elderly aunt readying a boy for school. "I've worked for Colonel Tan for nineteen years."

Shan grinned awkwardly. His eyes wandered to the lace doily on the table. It had been a long time, much longer than just his three years' imprisonment, since he had drunk tea with a proper lady. "At first I wondered who it was who had the courage to give the petition about the release of Lokesh to the colonel," Shan said. "I think I know now. You would have liked him. He sang beautiful songs from old Tibet."

"I am old-fashioned. Where I came from we were taught to honor the elderly, not imprison them."

What distant planet was that, Shan almost asked, then saw the way she was looking into her cup and realized that she needed to say something.

"I have a brother," she abruptly confessed. "Not much older than you. A teacher. He was arrested fifteen years ago for writing bad things and sent to a camp near Mongolia. No one talks about him, but I think about him a lot." She looked up with an innocent, curious expression. "You don't suffer, do you? I mean, in the camps. I wouldn't want him to suffer."

Shan took a long swallow of tea and looked up with a forced smile. "We just build roads."

Madame Ko nodded solemnly.

In the next moment a buzzer sounded and Madame Ko pointed toward the colonel's door. Li burst out of the conference room, staring uncertainly at Shan. As Madame Ko herded Shan into the colonel's office, he heard Li exclaim, "You're him!" in disbelief, just as she closed the door.

Tan was at his window, his back to Shan. The drapes were fully opened now, and in the brilliant light Shan could see the details of the back wall for the first time. There was a faded photograph of a girl with a much younger Tan beside a battle tank. To its left hung a map with the words nei lou, classified, printed boldly across the top. It was of the Tibetan border zones. Over the map hung an ancient sword, a zhan dao, the stout, two-handed blade favored by executioners of earlier centuries.

"Our man was picked up this morning," Tan announced without turning.

About the arrest, Li had said.

"In the mountains, where they usually hide. We got lucky. Fool still had Jao's wallet." Tan moved to his desk. "Public Security has an active file on him." He shot an impatient glance at Shan. "Sit down, dammit. We have work to do."

"The assistant prosecutor is already here. I assume I will be turning over my work to him."

Tan looked up. "Li? You met Li Aidang?"

"You never said there was an assistant prosecutor."

"It wasn't important. Li isn't capable, just a pup. Jao did all the work in the office. Li reads books. Goes to meetings. Political officer." Tan pushed forward a folder bearing the red stripes of the Public Security Bureau. "The killer was a cultural hooligan since his youth. 1989 riots in Lhasa. You know about the '89 Insurrection?"

Officially, the riot that had started when monks occupied the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa had not occurred. Officially, no one knew how many monks had died when the knobs opened fire with machine guns. In a country that practiced sky burial, it was easy to lose evidence of the dead.

"Several years later there was an incident here," Tan continued. "In the marketplace."

"I have heard. Some priests had been mutilated. The local people call them the Thumb Riots."

Tan ignored him. Was it true, Shan wondered, that Tan indeed had been the one to order the amputation of thumbs?

"He was there. Most of them got three years hard labor. He got six years, as one of the five organizers of the disturbance. Jao prosecuted him. The Lhadrung Five, the people called them." Tan shook his head in disgust. "They keep proving my point– that we were too easy on them the first time. And now, to lose Jao to one of them-" His eyes smoldered.

"I could make a list of the witnesses the tribunal will expect," Shan said woodenly. "Dr. Sung of the clinic. The soldiers who found the head. They will want a spokesman from the 404th guards, to talk about discovering the body."

"They?"

"The team from the prosecutor's office."

"To hell with Li. I told you."

"You can't stop him. He works for the Ministry of Justice."

"I told you. He's political. Just doing his rotation to build up chits back home. No experience with serious crime."

Shan caught Tan's eye to be certain he had heard correctly. Did Tan consider that there was part of the Ministry of Justice that was not political? It was no coincidence the Chief Justice of their country's supreme court was also the chief disciplinarian of the Party. "He works for the Ministry of Justice," Shan said again, slowly.

"I'll say he's too close. Like investigating the murder of his father. Judgment blinded by grief."

"Colonel, at first we had the death of a stranger which might have been covered up by an accident report. Maybe no one would have noticed. Then we had a strike at the 404th because of the death. A lot more people will notice. Now, you not only have a crime against a public security official, but also the arrest of a recognized public enemy. Everyone will notice. There will be intense political observation."

"I don't believe you, Shan. The politics don't scare you. You hold politics in contempt. That's why you're in Tibet."

He expected to find amusement on Tan's face. But it wasn't there. His expression was one of curiosity. "You want to withdraw because of your conscience, am I right?" Tan continued. "Do you believe our inquiries will be less than honest?"

Shan pressed his hands together until the knuckles were white. He had lost again. "There used to be struggle sessions, in my department in Beijing. I was criticized for failing to understand the imperative of establishing truth by consensus."

Tan stared at him in silence, broken at last by a sharp guttural laugh. "And they sent you to Tibet. This Minister Qin. He has some sense of humor." Tan's amusement faded as he studied Shan's face. He rose and moved back to the window. "You are wrong, Comrade," he said to the window, "to think men like me have no conscience. Do not hold me responsible for your failure to understand my conscience."

"I couldn't have said it better."

Tan turned with a look of confusion that quickly soured. "Don't twist my words, dammit!" he spat, and marched back to his desk. He folded his hands over the Public Security file. "I will say it only once more. This investigation will not be the responsibility of young pups in the prosecutor's office. Jao was a hero of the revolution. He was my friend. Some things are too important to delegate. You will proceed as we discussed. It will be my signature on the file. We will not have this discussion again."

Shan followed Tan's gaze to the door. It wasn't simply that Tan didn't trust the assistant prosecutor, Shan suddenly realized. He was frightened of Li.

"You cannot avoid the assistant prosecutor," Shan observed. "There will be questions about Jao that will have to be answered by his office. About his enemies. His cases. His personal life. His residence will need to be searched. His travel records. His car. There must have been a car. Find the car and you may find where Jao met his murderer."

"I knew him for years. I myself may have some answers. Miss Lihua, his secretary, is a friend. She will also help. For others you will prepare written questions which I will submit. We will dictate some to Madame Ko before you go."

Tan wanted to keep Li busy. Or distracted.

The colonel pushed the Bureau's file toward Shan. "Sungpo is his name. Forty years old. Arrested at a small gompa called Saskya, in the far north of the county. Without a license. Damned negligent, to let them return to their home gompas."

"You intend to try him for murder and then for practicing as a monk without a permit?" Shan could not help himself. "It might seem-" He searched for a word. "Overzealous."

Tan frowned. "There must be others at the gompa who could be squeezed. Going rate for wearing a robe without a license is two years. Jao used to do it all the time. If you need to, pick them up, threaten to send them to lao gai if they don't talk."

Shan stared at him.

"All right," Tan conceded with a cold smile. "Tell them I will send them to lao gai."

"You have not explained how he was identified."

"An informant. Anonymous. Called Jao's office."

"You mean Li made the arrest?"

"A Public Security team."

"Then he has his own investigation underway?"

As if on cue there was a hammering on the door. A high-pitched protest erupted, and Madame Ko appeared. "Comrade Li," she announced, her face flushed. "He has become insistent."

"Tell him to report back later today. Make an appointment."

A tiny smile betrayed Madame Ko's approval. "There's someone else," she added. "From the American mine."

Tan sighed and pointed to a chair in the corner shadows. Shan obediently sat down. "Show him in."

Li's protests increased in volume as a figure flew through the door. It was the red-haired American woman Shan had seen at the cave. Looks of confusion passed between Tan and the woman.

"There's really nothing else to say, Miss Fowler," Tan said with a chill. "That business is concluded."

"I asked to reach Prosecutor Jao," Fowler said hesitantly as she surveyed the office. "They told me to come here. I thought perhaps he had returned."

"You are not here about the cave?"

"You and I have said what we could. I will file a complaint with the Religious Bureau."

"That could be embarrassing," Colonel Tan retorted.

"You have reason to be embarrassed."

"I meant for you. You have no evidence. No grounds for a complaint. We will have to state that you encroached on a military operation."

"She asked to see Prosecutor Jao," Shan interjected.

Tan shot Shan a cold glare as Fowler walked to the window only a few feet from Shan. She wore blue jeans again, and the same hiking boots. Sunglasses hung on a black cord around her neck, over a blue nylon vest identical to the one Shan had seen on the American man at the cave. She wore no makeup and no jewelry except for tiny golden studs in her ears. What was the other name Colonel Tan had used? Rebecca. Rebecca Fowler. The American woman glanced at Shan, and he saw recognition in her eyes. You were there too, her eyes accused him, disturbing a holy place.

"I'm sorry. I didn't come to argue," she said to Tan in a new, conciliatory tone. "I have a problem at the mine."

"If there were no problems," Tan observed unsympathetically, "they wouldn't need you to manage the mine."

Her jaw clenched. Shan could see she was struggling not to argue with Tan. She chose to speak toward the sky. "A labor problem."

"Then the Ministry of Geology is the responsible office. Perhaps Director Hu-" Tan suggested.

"It's not that kind of problem." She turned and faced Tan. "I would just like to speak with Jao. I know he's supposed to be away. A phone number would do."

"Why Jao?" Tan asked.

"He helps. When I have a problem I can't understand, Jao helps."

"What sort of problem can't you understand?"

Fowler sighed and moved back to sit at Tan's desk. "My pilot production has begun. Commercial production is scheduled for next month. But first my pilot batches have to be analyzed and qualified by our lab in Hong Kong."

"I still don't-"

"Now the shipping arrangements have been accelerated by the Ministry without consulting me. Airport freight schedules have been changed without notice. Increased security. Increased red tape. Because of tourists."

"The season has started early. Tourism is becoming Tibet's strongest source of foreign exchange. Quotas have been increased."

"Lhadrung was closed to tourists when I took this job."

"That's right," Colonel Tan acknowledged. "A new initiative. Surely you will be glad to see some fellow Americans, Miss Fowler."

The sullen cast of Rebecca Fowler's face said otherwise. Was the mine manager merely disinterested in tourists, or actually unhappy about the prospect of visiting Americans? Shan wondered.

"Don't patronize me. It's all about foreign exchange. If you would only let us, we will produce foreign exchange as well."

Tan lit a cigarette and smiled without warmth. "Miss Fowler, Lhadrung County's first visit of tourists from your country must go perfectly. But still I don't-"

"To get my containers out on time I need double shifts. And I can't even put together half a shift. My workers won't venture to the back ponds. Some won't leave the main compound."

"A strike? I recall that you were warned about using only minority workers. They are unpredictable."

"Not a strike. No. They are good workers. The best. But they're scared."

"Scared?"

Rebecca Fowler ran her fingers through her hair. She looked like she had not slept in days. "I don't know how to say this. They say our blasting woke up a demon. They say he is angry. People are scared of the mountains."

"These are superstitious people, Miss Fowler," Tan offered. "The Religious Affairs Bureau has counselors experienced with the minorities. Cultural mediators. Director Wen could send some."

"I don't need counselors. I need someone to operate my machinery. You have an engineering unit. Let me borrow them for two weeks."

Tan bristled. "You are speaking of the People's Liberation Army, Miss Fowler. Not some wage laborers you can pull off the street."

"I am speaking of the only foreign investment in Lhadrung. The largest in eastern Tibet. I am speaking of American tourists who are scheduled to visit a model investment project in ten days. They are going to see a disaster unless we do something."

"Your demon," Shan said suddenly. "Does he have a name?"

"I don't have time to-" Fowler began sharply, then quieted. "Does it matter?"

"A similar sighting was made on the South Claw. In connection with a murder."

Tan stiffened.

Fowler did not immediately respond. Her green eyes fixed on Shan with a penetrating, hawklike intensity.

"I was not aware of a murder investigation. My friend Prosecutor Jao will be interested."

"Prosecutor Jao was quite interested," Shan offered, ignoring Tan's glare.

"So he's been informed?"

"Shan!" Tan rose and slammed a button at the edge of his desk.

"Prosecutor Jao was the victim."

A curse exploded from Tan's lips. He shouted for Madame Ko.

Rebecca Fowler sank back in her chair, stunned. "No!" The color drained from her face. "Dammit, no. You're kidding," she said, her voice breaking. "No. He's away. On the coast, in Dalian, he said."

"Two nights ago, on the South Claw"– Shan watched her eyes as he spoke-"Prosecutor Jao was murdered."

"Two nights ago, Jao and I had dinner," Fowler whispered.

In that instant Madame Ko appeared.

"I think," suggested Shan, "we need some tea."

Madame Ko nodded solemnly and moved back out the door.

Fowler seemed to try to speak, then she slumped forward, dropping her head into her hands until Madame Ko reappeared with a tray. The hot tea revived her sufficiently to find her voice. "We worked together on the investment applications," she began. "Immigration clearances. All the approvals." The words came out in a taut, nervous whisper. "He was interested in our success. He said he would buy me dinner if we brought in production before June. We made it. At least, we thought so. He called up last week. In a celebratory mood. Wanted to do the dinner before his annual leave."

"Where?" asked Shan.

"The Mongolian restaurant."

"What time?"

"Early. About five."

"Was he alone?"

"Just the two of us. His driver was in the car."

"His driver?"

"Balti, the little khampa," Fowler confirmed. "Always hovering around Jao. Jao treated him like a favorite nephew."

Shan studied Colonel Tan. Was it possible that Tan had actually forgotten such a vital point, had forgotten a possible witness?

"Where was he going after dinner?" Shan asked.

"The airport."

"Is that what he said? Did you see him leave?"

"No. But he was going to the airport. He showed me his ticket. It was a late-night flight, but it can take two hours to the airport and it was not a flight he would risk missing. He was very excited about leaving."

"Then why would he drive in the opposite direction?"

She did not seem to have heard. She appeared to be possessed by a new thought. "The demon," she said, her face suddenly gaunt. "The demon was on the Dragon Claws."

There was a hurried knock and Madame Ko appeared again, in front of the bespectacled Tibetan Shan had seen at the cave driving the Americans' truck. He was short and dark, with small eyes and heavy features that somehow distinguished him from most Tibetans Shan had known.

"Mr. Kincaid," the Tibetan blurted, extending an envelope. He saw Tan, and instantly turned his gaze to the floor. "He said give you this right away, don't wait for anything."

Rebecca Fowler stood and slowly, reluctantly, extended her hand. The Tibetan dropped the envelope into it and backed out of the room.

Tan watched him go. "You have a flesh monkey working for you?"

That was it, Shan realized. The man was a ragyapa, from the ancient caste that disposed of Tibet's dead.

"Luntok is one of our best engineers," Fowler said with a chill. "Went to university." Then her eyes moved to the paper and she started in surprise. She lowered the paper and glared at Tan, then read it again. "What's the matter with you people?" she demanded. "We have a contract, for Christ's sake."

She looked at Tan, then to Shan. "The Ministry of Geology," she announced in a tone that suggested Tan must already know, "has suspended my operating permit."

***

The empty barracks at Jade Spring Camp that had been made available to them was in such disrepair Shan could actually see the tin roof shudder and lift with each gust of wind. Sergeant Feng claimed the solitary bed typically occupied by the company's noncommissioned officer, and with a sweep of his hand offered Shan and Yeshe their choice among the twenty steel bunk beds that lined the remainder of the barracks. Shan ignored him, and began to spread his files on the metal table at the head of the columns of beds.

"I'll need a key to the building," he announced to Sergeant Feng.

Feng, rummaging through a cabinet for bedding, turned for a moment to see if Shan was serious. "Fuck off." He discovered six blankets, kept three, handed two to Yeshe and threw one to Shan. Shan let it drop to the floor and paced along the beds, looking for a place to hide his notes.

Less than thirty yards across the parade ground was the guardhouse. A tumble of withered heather blew across the grounds. A loudspeaker, dangling by a wire from its broken mount, sputtered a martial air, a military anthem rendered unrecognizable by static. Clusters of soldiers had gathered along the perimeter, resentfully studying the new guards posted at the brig.

"Knobs," Yeshe warned Shan as they approached the structure across the yard, his voice filled with alarm. "They don't belong here. It's an army base."

"We were expecting you," the Public Security officer in charge snapped to Shan at the entrance. "Colonel Tan advised us you would commence interrogation of the prisoner." He surveyed the three men as he spoke, not trying to conceal his disappointment. His eyes rested a moment on Sergeant Feng's grizzled face, passed over Yeshe, and fixed upon Shan, who still wore the anonymous gray pocketed jacket of a senior functionary. The officer hesitated a moment in front of the door, as though confused about his visitors, then finally shrugged.

"Get him to eat," he said, and stepped aside. "I can keep the bug from escaping," he went on as he unlocked the heavy metal door to the cell block. "But I can't keep him from starving himself. Gets too weak, we'll put a tube into his stomach. He'll have to be on his feet."

Spoken, Shan considered, like one seasoned in the choreography of the people's tribunals. The prisoner was expected to stand in front of the court, head bent in remorse. The exquisite drama of a capital trial was always heightened by a show of physical strength on the part of the accused, so it could be more obviously broken by the will of the people.

The corridor, dank with the smell of urine and mildew, was lined with cells on either side, separated by concrete walls. The only light that reached the cells was from dim bulbs hung along the center of the corridor. As his eyes adjusted to the grayness Shan saw that the cells were empty, containing only metal buckets and straw pallets. At the end of the corridor was a small metal desk at which a single figure slumped, asleep, his chair leaning against the wall.

The officer snapped out a single sharp syllable and the man tumbled out of the chair with a disoriented salute. "The corporal can attend to your needs," the officer said, and wheeled about. "If you need more men, my guards are available."

Shan stared after him in confusion. More men? The corporal ceremoniously produced a key from his belt and opened a deep drawer in the desk. He gestured in invitation. "Do you have a favored technology?"

"Technology?" Shan asked distractedly.

The drawer contained six items resting on a pile of dirty rags. A pair of handcuffs. Several four-inch splinters of bamboo. A large C-clamp, big enough to go around a man's ankle or hand. A length of rubber hose. A ball peen hammer. A pair of needle-nose pliers, made of stainless steel. And the Bureau's favorite import from the West, an electric cattle prod.

Shan fought the nausea that swept through him. "What we need is to have the cell open." He slammed the drawer shut. The color had drained from Yeshe's face.

The corporal and Feng exchanged amused glances. "First visit, right? You'll see," the corporal said confidently, and opened the door. Feng sat on the desk and asked the guard for a cigarette as Shan and Yeshe stepped inside.

The cell was designed for high occupancy. Six straw pallets lay on the floor. A row of buckets lay along the left wall, one holding a few inches of water. Another, turned upside down, served as a table. On it were two small tin cups of rice. The rice was cold, apparently untouched.

The far wall of the cell was in deep shadow. Shan tried to discern the face of the man who sat there, then realized he was facing the wall. Shan called for more light. The guard produced a battery-powered lantern which Shan laid on an upturned bucket.

The prisoner Sungpo was in the lotus position. He had torn the sleeves from his prisoner's tunic to fashion a gomthag strap, which he had tied behind his knees and around his back. It was a traditional device for lengthy meditation, to prevent the body from tumbling over in exhaustion while its spirit was elsewhere. His eyes seemed focused somewhere beyond the wall. His palms pressed together at his chest.

Shan sat by the wall facing the man, folding his legs under him, and gestured for Yeshe to join him. He did not speak for several minutes, hoping the man would acknowledge him first.

"I am called Shan Tao Yun," he said at last. "I have been asked to assemble the evidence in your case."

"He can't hear you," Yeshe said.

Shan moved to within inches of the man. "I am sorry. We must talk. You have been accused of murder." He touched Sungpo, who blinked and turned to look around the cell. His eyes, deep and intelligent, showed no trace of fear. He shifted his body to face the adjoining wall, the way a sleeping person might roll over in bed.

"You are from the Saskya gompa," Shan began, moving to face him again. "Is that where you were arrested?"

Sungpo clasped his hands together in front of his abdomen, interlocking the fingers, then raised his middle fingers together. Shan recognized the symbol. Diamond of the Mind.

"Ai yi!" gasped Yeshe.

"What is he trying to say?"

"He isn't. He won't. They arrested this man? It makes no sense. He is a tsampsa," Yeshe said with resignation. He rose and moved to the door.

"He is under a vow?"

"He is on hermitage. He must have seclusion. He will not allow himself to be disturbed."

Shan turned to Yeshe in confusion. It had to be some kind of very bad joke. "But we must speak to him."

Yeshe faced the corridor. There was something new on his face. Was it embarrassment, Shan wondered, or even fear? "Impossible," he said nervously. "It is a violation."

"Of his vows?"

"Of everyone's." Yeshe spoke in a whisper.

Suddenly Shan understood. "You mean yours." It was the first time Shan had heard Yeshe acknowledge the religious obligations he learned as a youth.

Shan placed his hand on Sungpo's leg. "Do you hear me? You are charged with murder. You will be sent to a tribunal in ten days. You must talk with me."

Suddenly Yeshe was back at his side, pulling him away. "You don't understand. It is his vow."

Shan thought he had been prepared for anything. "Because of his arrest? As a protest?"

"Of course not. It has nothing to do with that. Look at his file. He would not have been taken from the gompa itself."

"No," Shan confirmed from his memory of the report. "It was a small hut a mile above the gompa."

"A tsam khan. A special sort of shelter. Two rooms. For Sungpo and an attendant. They seized him out of his tsam khan. I don't know how far he is."