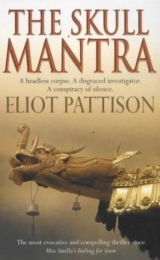

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Shan pressed his palms together and bowed his head in greeting. "Rinpoche. If I could ask-"

"There are so many things to consider," the ancient one interrupted. His voice was surprisingly strong. "This mountain. The dogs. The way the mist falls down the slopes, different each morning." He turned to Shan. When he shifted his body the robe barely moved. "Some days I feel like that. Like mist sliding down the mountain." He looked back down the valley and pulled his robe tighter, as if cold. "Jigme brings a melon sometimes. We eat it and Jigme will watch."

Shan sighed and stared out over the landscape. He would never have a chance to speak with Sungpo. Je, his lama, had been Shan's only hope for an intermediary. "When we climb to the top of the mountain, you know what we do?" the lama asked. "Just as I did when I was a novice. We make little paper horses and fly them away in the wind." He paused as if Shan required an added explanation. "When they touch the earth they become real horses to help travelers through the ranges."

There was movement beside Je. The raven had landed an arm's length away.

"They are praying, my friends and teachers," Je began again. "All of them, and the bombs are beginning to fall. There is time to leave but they will not. I must take the young ones into the hills. The ones who stay are dying, just saying their rosaries and dying in the explosions. As I am leaving with the boys something is hitting me in the face. It is a hand, still holding its rosary."

It was 1959, Shan calculated, or at the latest 1960, when the PLA bombed the gompas from the air.

"Was it right?" Je continued. "That is always the temptation. To ask if it was right. It is the wrong question, of course."

Suddenly Shan realized that the old man knew exactly why Shan was there.

"Rinpoche," he said slowly, "I would not ask Sungpo to break his vow. I only ask him to join me in finding the truth. There is a murderer somewhere. He will kill again."

"The only one who can find the murderer is the murdered," Je said. "Let the ghost take its revenge. I am not worried about Sungpo. But Jigme. Jigme is lost."

Shan realized he had to let the old man lead the conversation. The wind increased. He fought the temptation to grab Je's robe, lest he be lifted into the clouds. "Jigme does not study at the gompa."

"No. He abandoned studies to go with Sungpo. He never belongs. Being a gompa orphan, it is like being a small bird forced to live all its life in a rainstorm."

A shiver of realization moved down Shan's spine. During the occupation of Tibet and again during the Cultural Revolution, monks and nuns had been forced, sometimes at bayonet point, to break their vows of celibacy, sometimes with each other, sometimes with soldiers. In some regions the offspring had been gathered into special schools. Elsewhere they formed gangs. There were several of the mixed-blood gompa orphans in the 404th, who had followed their priests to jail.

"Then for Jigme, help me bring Sungpo back."

The old man's eyes were closed now. "After the gompa was destroyed," he murmured, "I could see the rising moon better."

***

The truck had already begun the long climb toward the pass when Shan asked the name of the gompa at the head of the valley, the compound they had passed at dawn. Yeshe did not reply.

Feng slowed and read the map. "Khartok," he said impatiently. "They call it Khartok."

Shan grabbed one of the files provided by Tan, glanced at it, and threw his hand toward Sergeant Feng. "Stop. Now."

"There isn't time," Feng protested.

"You would rather leave before dawn tomorrow and come back here?"

"It is late. They will be preparing for last assembly, lighting the lamps soon," Yeshe said insistently. "We can try a telephone interview."

Feng turned, looked into Shan's eyes, and without another word turned and moved back down the valley.

Yeshe groaned and covered his eyes with his hand, as if he could not bear to see more.

It wasn't pastures he had seen in front of the buildings. It was ruins, fields of stone that began half a mile from the gompa. There was no order to the stones. Some were in piles, others scattered as though they had been thrown from the overhanging mountains. But every stone had been squared by a mason.

Closer to the gompa the foundations of several buildings had been turned into gardens. A dozen figures in red robes leaned on their hoes to gaze at the unexpected vehicle. As they eased to a stop Shan saw that new construction lay beyond the foundations. The main wall was being rebuilt and extended. Stacks of fresh lumber and pallets of cement wrapped in plastic were arrayed along the treeline.

Yeshe lay on the back seat, an arm thrown over his eyes.

"You know gompas. You know the protocols," Shan said impatiently. "I need you."

Feng opened the rear door. "You're not sleeping, Comrade." He pulled on Yeshe's arm. "Hell, you're panting like a cornered cat."

Shan ventured into the courtyard alone. The same structures he had seen at Saskya were there, but freshly painted and on a much larger scale. Not one but five chortens were arranged about the grounds, capped by suns and moons of newly worked copper. A better investment, Shan remembered. Director Wen of the Religious Affairs Bureau had said Saskya was not permitted to rebuild because the gompa in the lower valley was a better investment.

A middle-aged monk with a row of gold embroidery on his sleeve appeared on the steps of the assembly hall. He threw his arms out in a gesture of welcome and trotted down the steps. Shan watched as the other monks looked up at the newcomer. Some nodded deferentially, others quickly averted their eyes. The man was a senior lama, probably the abbot. But why, Shan wondered, didn't the man seemed surprised to see him? The lama interrupted a young student who was raking the gravel and dispatched him into the hall, then pointed toward an herb garden in the shelter of the wall. Shan silently followed him into the garden. Wooden benches were arranged in rows between the plant beds, as though for students receiving instruction. At the end of the garden an old monk was on his knees, pulling weeds.

"We will have the plans finished soon," the lama announced as soon as Shan sat on the front bench.

"Plans?" The young monk appeared with a tray of tea, poured it for them, and retreated with a hurried bow of his head.

"For the first restoration of the college buildings. Tell Wen Li that the plans are almost finished." There was something odd about the lama's demeanor. Shan searched for a way to describe it. Social, he decided. Almost urbane.

"No. We are here about Dilgo Gongsha."

The lama did not relent. "Yes, the plans are nearly complete," he said, as though the topics were connected. "The Bei Da Union is helping, you know. We are helping each other with our reconstructions."

"The Bei Da Union?"

The lama paused and looked at Shan as though for the first time. "Who are you, then?"

"An investigation team. From Colonel Tan's office. I am reviewing the facts of the Dilgo Gongsha matter. He was a resident here, was he not?"

The lama's eyes slowly surveyed Shan, then shifted to Feng and Yeshe, who were inching along the shadows of the walls. As the two passed a small gathering of monks, someone called out in surprise, as if in greeting. Someone else called, in a tone Shan didn't recognize at first. Anger. Yeshe moved behind Feng.

"The last time we saw Dilgo," a gentle voice announced from behind Shan, "he was passing into that peculiar hell for souls taken by violence." Shan's host stood and put his palms together in greeting. It was the old monk who had been tending weeds. His robe was stained from garden work, his fingernails filled with dirt. "We performed the rights of Bardo. By now he is an infant. He will grow to bless those around him once again." He had a twinkle in his eyes, as though the memory of Dilgo caused him joy.

"Abbot," the lama said with a bow of his head. "Forgive me. I thought you were in your meditation cell."

Abbot? Shan looked in confusion at the first lama.

"You have met our chandzoe," the abbot offered, noticing Shan's glance. "Welcome to Khartok."

"Chandzoe?" It was not a term Shan had heard in any of the winter tales.

"The manager of our secular affairs," the abbot explained.

"Secular affairs?"

"Business manager," the first lama interjected, pouring a cup of tea for the abbot and gesturing for him to sit.

"Why would you speak of our Dilgo?" The abbot asked the question the way a child might, with wide, innocent eyes.

"He was found guilty of killing a man by stuffing his throat with pebbles. The man happened to be the Director of the Religious Affairs Bureau."

The chandzoe frowned. The abbot looked into his teacup.

"In the old days it was the traditional method for killing members of the imperial family," Shan said. "Even in battle they could only be taken and later suffocated."

"Forgive me," the chandzoe said. "I do not understand your point." He seemed to be expressing not confusion, but disappointment with Shan.

"Only that it was a very traditional sort of murder for a senior government official."

"And as they said at trial," the chandzoe said with a hint of impatience. "Khartok is a very traditional gompa. You cannot execute Dilgo twice." A murmur among the monks in the courtyard caught Shan's attention. He followed their stares toward Feng and Yeshe, in the shadow near the edge of the garden.

"If I were going to murder someone I would be sure not to use a method that would be associated with me or my beliefs."

Suddenly the chandzoe stood. "Yeshe?" he called out. "Is it Yeshe Retang?"

Yeshe cowered a moment at the corner of the garden, then saw the enthusiasm in the chandzoe's face and stepped closer. "It is, Rinpoche. I am honored you remember."

The chandzoe threw out his arms again, in the expression Shan had seen when he first appeared on the stairs, and moved to pull Yeshe out of the shadow. Yeshe stood stiffly, glancing uneasily at Shan.

The chandzoe shifted his eyes from Shan to Yeshe, obviously confused.

"My detention has recently concluded, Rinpoche. I am on this assignment now. Temporarily."

Yeshe cast a pleading glance at Shan, which the chandzoe seemed to follow with great interest. The chandzoe watched Shan now, waiting for Shan to speak. The Chinese in charge.

"His commitment to reform was exemplary," Shan heard himself say. "He has unusual qualities of-" he searched for a word-"dedication."

The chandzoe nodded with satisfaction.

"I can get a job in Sichuan, I think," Yeshe said uneasily.

"Why not return here?" the chandzoe asked.

"My record. I cannot be licensed."

"Your reeducation is completed. I could talk to Director Wen." He spoke as though he were somehow obligated to Yeshe.

Yeshe's eyes grew round with surprise. "But the quota."

The chandzoe shrugged. "Even if it's a problem, we have no quota on workers for the reconstruction." He pulled Yeshe's hands open and squeezed one. "Please come see the new works," he said, and pulled Yeshe toward the assembly hall. Slowly, with tiny steps that made it seem he was fighting an invisible force, Yeshe moved toward the hall. As he did so, Shan saw another monk on the steps, facing Yeshe. His hands formed a mudra that seemed aimed at Yeshe.

Yeshe looked to Shan in confusion. Shan nodded, and the two men moved across the courtyard.

The abbot watched the chandzoe without expression, then sighed and turned to Shan. "You assume that murderers lie," he said, as if he had not noticed the interruption. "Dilgo would not lie. It would violate his vows."

"Did he do the killing, then?" Shan asked.

The abbot would not answer.

"Taking a life would have been a far more severe violation of his rules," Shan pointed out.

The abbot finished his tea and dabbed his mouth with the sleeve of his robe. "They are both prohibited by the 235 rules," he said, referring to the rules of conduct prescribed for an ordained priest.

"I am confused," Shan said. "Those who break their vows are reincarnated as lower life forms. You have already said you believe him to have returned as a human."

"I, too, am confused. What exactly do you want of us?"

"A simple answer. Do you believe that Dilgo killed the Director of Religious Affairs?"

"The government exercised its authority. Dilgo did not protest. The case was closed."

Why did it surprise him, Shan thought, to find that the head of a thriving gompa was also a politician? "Did he do it?"

"Everyone has a different path to Buddhahood."

"Did he do it?"

The abbot sighed and looked into a passing cloud. "It would have been more likely for Mt. Kailas to collapse into the earth from the weight of one bird than for Dilgo to commit such an act."

Shan nodded heavily. "Another such bird has been set into flight."

The abbot looked with a new sadness into Shan's eyes.

"Do you ever think about it, about where the sin lies?" Shan asked.

"I do not understand."

"It is easy for them; it is the way they stay in power. Danger is part of power, like shadow is part of light. Sometimes, if no one threatens it, it must invent threats. It is just as easy for you, to justify what happened to Dilgo. You probably decided that it is as much the nature of things as the tidal wave of soldiers that washed over the gompas in 1959. It was his destiny, you can say, and besides, Dilgo is reincarnated in a better life. But it is not so easy for those in between."

The abbot no longer looked into Shan's eyes.

"Did you expel Dilgo?"

"He was not expelled."

"He was convicted of murder but you did not expel him. Instead you performed the rites of Bardo for him."

The abbot looked into his hands.

Shan consulted his notebook. "They found his rosary at the murder scene. A very special rosary. Beads carved like tiny pine cones, made out of pink coral, with lapis marker beads. Very old. Must have been brought from India. The file said it was unique, the only one of its kind."

"It was his rosary," the abbot confirmed. His voice grew very still. "It was the proof against him."

"Did he explain how it got there?"

"He could not explain it."

"Had he lost it?"

"No. He did not miss it. In fact, he said he had it when he was arrested, when he was taken from his pallet, still sleeping. It was a miracle perhaps, that it could have been transported somewhere and returned that way. Dilgo said maybe it was a message."

"Why did he not protest?" Shan said. "Why did he not argue his defense? If you knew he was innocent, why did you not defend him?"

"We did everything we could."

"Everything?" Shan slowly pulled the case file from the canvas bag he was carrying and dropped it on the bench between them. Shan had read the statement prepared for the abbot. The abbot had condemned the act of violence and apologized on behalf of the gompa and the church.

The abbot stared at the file, then looked up without blinking. "Everything."

He was wrong to expect any of them to feel guilty, Shan realized. Everyone in the drama of Dilgo, from the abbot to Prosecutor Jao, even to the accused, had played his role correctly.

The abbot rose and began to move back to his weeds.

"Then tell me this," Shan said to his back. "Have you heard that a Buddhist demon was at the site of the murder?"

The abbot turned with a frown. "Traditions die hard."

"So you did hear such a rumor?"

"Whenever a public figure dies there will be those who say it was this demon or that spirit who took revenge."

"And there was such a report that night?"

"There was a full moon that night. A herder reported that he saw the horse-headed demon on a hill above the highway, doing something like a dance. The one called Tamdin. Among the pebbles that suffocated the Director of Religious Affairs was one bead, a rosary bead in the shape of a skull. The kind that Tamdin carries." Shan had touched such a rosary. The rosary of a demon.

"A shrine was built by the local people, on the spot, to praise their protector."

Doing a dance on a hill by the highway. Under a full moon. As though, Shan considered, Tamdin wanted to be seen.

"Shrines were built after the other murders, too. People say a truck driver saw Tamdin when the Director of Mines was killed. As I said, there're always such rumors when an official dies. Tamdin is a favorite of the people. Very fierce, no mercy in defending the church. A very old demon, one of those they call a country god, from the old Tibetan shamans before the days of Buddhism. As the people evolved to Buddha they brought Tamdin with them."

From the other side of the courtyard a sudden uproar of animals interrupted them. A gate had been opened and a huge pack of dogs was entering. Priests were feeding the dogs, more dogs than Shan had ever seen gathered in one place. He saw at least thirty and more were trotting through the gate.

Segeant Feng cursed and dropped onto the bench beside Shan, not taking his eyes off the animals. Three large black mastiffs, of the kind herdsmen used to patrol against wolves, lingered in the shadows, as though sensing that Feng and Shan were intruders. Feng's hand moved to his gun.

"Ai yi!" cried one of the monks as he saw Feng's reaction. He rushed to stand in front of the dogs. "They are under our protection," he said in a pleading tone. "They are part of Khartok gompa. They come from all over Tibet to be with us."

"Damned mongrels," Feng growled. "Where I come from they are raised for the pot."

The monk could not hide his horror. "They are part of us. The ones who remember. It is why they come here."

"Remember?" asked Shan.

"Priests who failed," the monk explained. "The dogs are reincarnations of priests who broke their vows."

As the monk spoke Yeshe appeared on the steps with the chandzoe. From the far side of the courtyard someone else shouted angrily toward Yeshe. The chandzoe put his hand on Yeshe's shoulder as though to calm him. The monk on the steps was still there, still aiming his mudra at Yeshe.

At last Shan recognized the mudra. It was to bestow forgiveness. A cold wave of realization swept through him as he looked back at Yeshe, as though for the first time. He had been so blind. He had asked Yeshe everything about himself except the most important question of all.

***

Two hours later they were at the top of the pass, so high that the stars on the far horizon were below them. Shan, in a drowsy haze, wanted the feeling of drifting through space to continue, until he floated into a world where governments did not lie, where jails were for criminals, where men were not killed with pebbles.

He became aware of a liquid rattle in the back seat. Yeshe had a rosary.

An hour later, as they moved into the crossroads at the head of Lhadrung valley, Shan put his hand on Feng's arm. "Go left."

"Lost your track, Comrade," Feng grunted. "The barracks are to the right. Sixty minutes more and we'll be in our bunks."

"To the left, to the 404th worksite."

"That's miles out of the way," Feng protested.

"That's where we are going."

Feng pulled the truck to a stop as it passed the intersection. "It will be nearly midnight by the time we get there. It's empty."

"Improves the odds."

"The odds?"

"Of meeting the ghost."

Feng shuddered. "The ghost?"

"I want to ask who killed him."

Feng turned on the cab light and stared at Shan, as though hoping for evidence that this was a joke.

Shan returned the stare without expression. "Scared of a ghost, Sergeant?"

"Damned right," Feng shot back, too loudly. He slammed the truck into gear and turned around.

***

A half mile from the bridge Shan instructed Feng to turn off the lights. The 404th worksite was as empty as death as they rolled to a stop near the bridge. Feng climbed out and immediately produced his pistol. Shan said nothing but began walking toward the mountain. After thirty paces he looked back to see Feng circling the truck, as if on sentry duty.

Shan paused at the end of Tan's bridge and gazed skyward, still in awe of the stars. He was afraid that if he reached out he would touch them. His knees were trembling.

He walked up the roadbed to the small cairn marking the site of Jao's murder and sat on a rock. There was no wind on the mountain. This was when the jungpo would prowl. This was when demon protectors would strike. He found his hand over his pocket which held the charm that called Tamdin. What were the words from Khorda's skull mantra? Om padme te krid hum phat.

A pebble moved behind him. His heart leapt into his throat as a shadow appeared beside him. It was Yeshe.

"It was a night like this," Shan observed, trying to calm himself. "Prosecutor Jao was driven to the bridge. Someone was here. Someone he knew."

"I never understood. Why here?" Yeshe asked. "It's so far from anywhere."

"That's the reason. The road goes nowhere. No danger of being discovered by passersby. Easy to escape." But that was not all. The mountain still had not given up its secret.

"So they walked with Jao," Yeshe said. "To look at the stars?"

"To talk. In private. Someone stayed below."

"The driver."

"I am here with Jao," Shan said, switching to the view of the murderer who had lured Jao to the mountain. "I brought him up here to tell him a secret. But something happened to surprise him. A loose rock. The tingle of metal. He senses his attacker at the last minute, and turns to struggle with him, long enough for Jao to pull an ornament from the costume." Shan stood with a rock in his hand, acting out the scene. "Then I grab a rock and hit him from behind." He threw the rock to the ground forcefully. "I arrange him neatly after I empty his pockets of identity. Then Tamdin uses his blade."

"So there're two killers."

"I think so now. Jao didn't come here with someone in a demon costume. He came with a friend, who had the demon waiting." Shan took a step away, back into character. "I don't want to watch." Shan walked toward the edge of the cliff. "I don't want blood to spray on me. I come to the edge and throw away what I took from his pockets." He picked up a stone and moved to the brink of the cliff. Extending his arm over the void, he released the stone.

"You told me why you were sent back from university," he said after a moment, still facing the abyss. "But you never said why you went to the university." Investigations, meditations, careers, relationships were much the same, he mused. They failed because no one thought to ask the right question.

Shan sensed Yeshe moving toward him, and stepped to the very edge, until his toes hung out over the blackness.

"It was an honor to be invited to the university," Yeshe said in a hollow voice.

A tiny shove, a mild gust of wind would be all it took. Yeshe could just slip and fall against Shan, and he would drop. On a night like this maybe you never hit the bottom. There would only be blackness, then a deeper blackness.

"But why would Yeshe Retang be invited? An unknown monk in a remote gompa?"

Yeshe moved beside him now, as if willing himself to take as much risk as Shan.

"They didn't start reconstruction at Khartok until after you left," Shan pointed out. "The chandzoe, he treated you like his hero. Like he owed you. As if Khartok received favors after you left."

"I promised my mother I would be a monk," Yeshe said to the stars. "I was the oldest son. It was the tradition for Tibetan families, until Beijing came. The oldest son would have the honor of serving in a gompa. But I wasn't a good monk. The abbot said I had to reduce my ego. He gave me work in the villages, to see the suffering of the people. Twice a week I drove a truck to bring sick children to the gompa."

A nighthawk called out on the slope behind them.

"He was just lying there, by the road. I thought I could save him. I thought I should push him over to get the pebbles out so he could breathe. I tried. But he was already dead."

"You mean you discovered the body of the Director of Religious Affairs."

"I never understood why he was up there all alone," Yeshe whispered.

"And Dilgo of your gompa was executed for it." Shan remembered the missing sheets from the files. Witness statements.

"When I turned him over it was there. I recognized it immediately."

"You mean the rosary belonging to Dilgo?"

Yeshe didn't respond.

"So you were a witness against him."

"I told the truth. I found a dead Chinese. He had Dilgo's rosary under him."

It was such a perfect parable. Antisocial cultist condemned by the testimony of a member of the new society, who happened to belong to his own gompa. Proof of how evil the old order was and how virtuous the new could be. "They sent you to the university as your reward."

"How could I refuse? How often does a monk get offered university? How often does any Tibetan get offered university? They said it wasn't a reward. They said my actions had simply demonstrated that I belonged in university, that I was a leader who should have been there all along."

"Who gave it to you?"

"Prosecutor Jao. Religious Affairs. Public Security. They all signed the paper."

It meant nothing about who killed Jao, or who might be trying to manipulate Yeshe again. Granting such rewards was all in the course of business in administering Chinese justice. Someone might have used Yeshe, knowing he had a pattern of driving on the route. Or his involvement might have been entirely coincidental. What mattered was that Yeshe had proved himself susceptible, and someone else was seeking to influence him in the same manner now. Not Zhong. Warden Zhong was just a conduit, just cooperating to secure Yeshe's labor for another year.

"I said it first," Yeshe offered, as if it was an urgent afterthought.

"First?"

"I gave the statement long before they offered the university to me."

"I know."

"They said it was for being a good citizen." He was whispering again. "Only thing is," he added forlornly, "I don't know what it means anymore– to be a good citizen."

As they watched the stars, the pain seemed to drift out of their silence.

"After we saw Religious Affairs," Yeshe said, "after Miss Taring said artifacts were still being discovered and put in the museums, I wondered. What if someone had found a second rosary like Dilgo's? What if I had lied and didn't know it?"

Shan put his hand on Yeshe's arm and eased him back from the edge of the cliff. "Then you need to find out."

"Why?"

"For Dilgo."

They sat on a boulder and let the silence wash over them again.

"Do you think it's true what they say?" Yeshe asked.

"What is true?"

"That Jao's ghost is staying here, seeking vengeance."

"I don't know." Shan looked out into the night. "If my soul were set adrift," he said slowly, "I'd never look back."

They spoke no more. Shan had no idea how long they sat. It could have been ten minutes, or thirty. A shooting star arced across the sky. Then, just as abruptly, there was a loud sound, a wrenching, haunting half-moan, half-scream like he had never heard before. It came from below them, and seemed to pierce the skin around his spine. It was not the sound of a human.

Suddenly there were three gunshots, then dead silence.