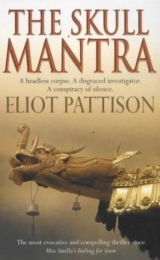

Текст книги "The Skull Mantra"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Chapter Nineteen

Yeshe stared at the body in utter desolation. The eyes of the old man at the foot of the pallet welled with tears. A voice in the back shouted out an epithet in Tibetan. The priest who had been conducting the Bardo ceremony began to speak with a chilling ferocity, a dark chant Shan had never heard before. He was glaring at Yeshe as he spoke, his invective coming faster and louder. Yeshe stared at him mutely, his face drained of color.

Shan pulled Yeshe's arm but he seemed unable to move. The attending priest, tears pouring down his cheek, was frantically searching through the hair on the crown of Je's head. If properly prepared, Je's soul would have drifted out a tiny hole thought to be on every human's crown.

"Get him a bone!" someone yelled from the rear.

"His name is Yeshe!" another shouted. "Khartok gompa."

Shan put his shoulder into Yeshe and pushed him out of the yurt. Something inside Yeshe had collapsed. He seemed suddenly feeble and senseless. Shan took his hand and led him to the cell block. Inside, Sungpo was chanting now, a new mantra, a sad mantra. Somehow he knew.

"It doesn't matter," Shan said to Yeshe, not because he believed it but because he couldn't bear for Yeshe to become still another victim.

"Above all, it matters." Yeshe was shaking now. He stepped into an empty cell and gripped the bars to steady himself. There was a fear on his face that Shan had never seen before. "What I did– it destroyed the moment of his transition. I ruined his soul. I ruined my soul," he said with chilling certainty. "And I don't even know why."

"You did it to help Sungpo. You did it to find justice for Dilgo. You did it for the truth." He hadn't told Yeshe about the coral rosary in the Lhasa museum, the duplicate of Dilgo's, the rosary that no doubt had been planted to implicate Dilgo and ensnare Yeshe in the lies. It didn't matter that Yeshe learned of the evidence, because his heart had learned of the lie long ago.

"Your justice. Your damned justice," he groaned. "Why did I believe you?" He seemed to be getting smaller, shrinking before Shan's eyes. "Maybe it's true," Yeshe said, with a realization that seemed to horrify him. "Maybe you did summon Tamdin. Maybe he's been lurking around us all the time. Maybe he used you to create the ruthlessness. He lays waste to everything, lays waste even to souls, in the search for truth."

"You can go to your gompa. You want to be a priest again, you've shown me. They will help you."

Yeshe moved to the back wall and slumped against it. When he looked up he appeared so gaunt it seemed the flesh had shriveled on his bones. His color had not returned. He was not Yeshe, but a ghost of Yeshe. "They will spit on me. They will drive me from the temples. I can never go back now. And I can't go to Sichuan. I can't be one of them anymore. I don't want to be a good Chinese," he said. "You destroyed that for me, too." He fixed Shan with haunted eyes. "What have you done to me? I took four. I might as well have jumped from a cliff." Throw him a bone, the monks had said. "For nothing."

He slowly slid down the wall to the floor. Tears were streaming down his cheek. He found his rosary and pulled it apart. The beads slowly dropped onto the floor and rolled away.

Numbed by his helplessness, Shan filled a tea mug with water and handed it to him. It fell through Yeshe's hands and shattered on the floor. Struggling to find words of comfort, Shan began picking up the pieces of porcelain, then stopped and dropped to his knees. He stared at the shards in his hands.

"No," Shan said excitedly. "Je told us exactly what we needed to know. Look!" he said, shaking Yeshe's shoulder as he held up a shard. "Do you see it?"

But Yeshe was beyond hearing him. With an aching heart Shan rose, gave Yeshe one last painful look, then darted out of the building.

***

When Sergeant Feng and Shan arrived at the market, Feng made no effort to leave the truck. Shan moved straight toward the healer's shop. But he did not enter Khorda's hut. He stood in the alley beside it. A youth in a herder's vest appeared beside him. "Wait," the youth said urgently. Moments later he returned with the scar-faced purba.

"You don't need to go to the mountain," Shan told him. "You don't need to sacrifice yourself. I found another way."

The purba looked at him skeptically.

"I need to go with the food today. To the 404th," Shan said.

"We don't deliver the food. It is the responsibility of the relief association."

"But sometimes you go with them. There is no time for games. I know what happens now. Sometimes you leave someone behind."

"I don't understand," the purba said stiffly.

"The camp of the 404th is built on rock. There is no tunnel. There is no hole in the wirefence. And no one is flying through the air like an arrow."

The purba surveyed the marketplace over Shan's shoulder. "Have you finished your investigation?"

"I've seen Trinle. Not at the 404th."

"Trinle is a very holy man. He is often underestimated."

"I don't underestimate him. Not now. For him the 404th is not a prison. He comes and goes on the business of Nambe gompa. He comes and goes with the purbas. There is no one else who could do it for him."

"And how would we perform this magic?"

"I don't know exactly. But it shouldn't be difficult so long as the headcount isn't changed."

The purba winced, as though he had bitten something sour. "To take the place of a prisoner would be foolhardy. It would risk immediate execution."

"Which is why it is a purba who does it."

The man did not react.

"Trinle is sick more than most," Shan said. "We have become used to it. Sometimes he stays confined to his bunk with his blanket over his head. Now I know why. Because it isn't him. I can guess how it is done. On agreed days purbas help with the food, when the relief association serves meals. One man wears prison clothes under his civilian clothes. When Trinle reaches the food tables there is a distraction. Perhaps he ducks under the tables and puts on the civilian clothes. The purba switches with him, and stays in the 404th until Trinle returns. The guards are not fastidious. They don't know every prisoner's face. As long as the headcount is the same, how could there be an escape? And as long as his face stays hidden, what other prisoners will suspect?"

The purba stared at Shan. "What exactly do you want?"

"I need to get through the dead zone. Today."

"Like you said, it is very dangerous. Someone could be killed."

"Someone has been killed. How many more does it take?"

The purba looked out over the market as though in search of the answer. "Cabbages," he announced suddenly. "Watch for cabbages," he said, and seemed to glide away.

Twenty minutes later as Feng drove through the town traffic, a cart of cabbages upturned directly in their path. As Feng moved into reverse, a second cart suddenly blocked them.

Instantly Shan jumped out. "This is what you must do. Go to Tan. Tell him he must come with you. To the 404th. Meet me at the wire with him in two hours." He turned, ignoring Sergeant Feng's weak protest, and disappeared into the crowd.

An hour later he was inside the 404th, wearing an oversized wool hat and the armband of the charity, serving out bowls of barley gruel. When half the line had filed past, a bucket of water was dropped on a guard's foot. The guard shouted. The Tibetan carrying the bucket fell backward, knocking over a prisoner. More guards ran to investigate.

In the ensuing confusion Shan ducked under the opposite end of the long table, which had been draped with a dirty piece of felt, discarded his jacket and entered the line, wearing prison clothes provided by the purbas.

Choje was not eating. Shan found him meditating in his hut, and sat in front of him. His eyes flickered open and he put his hand on Shan's cheek, as though making sure he was real. "It is a joy to see you. But you have selected a troubled moment to return."

"I needed to speak to the abbot of Nambe gompa."

"Nambe was destroyed."

"Its buildings were destroyed. Its population was imprisoned. But the gompa lives."

Choje shrugged. "It could not be allowed to die."

"Because of the promises made about Yerpa. To the Second Dalai Lama."

Choje showed no surprise. "More than a promise. A sacred duty." His lips curled into a weak smile. "It is wonderful, is it not?"

"Do the purbas know, Rinpoche?"

Choje shook his head. "They want to help all prisoners. It is the right thing to do. But they never needed to know our secret. We have a duty not to tell. It is enough for them to know that Nambe gompa lives, that by helping Trinle they keep it alive."

Shan nodded as Choje confirmed his suspicion. "I understand now why Trinle had to go, why the arrow rite finally seemed to work. You had to be certain the knobs acted in public. Once the miracle happened witnesses were sure to come, as word leaked out of the magic."

Choje looked into his hands. "We were worried, Trinle and I, that maybe what we did was a lie."

"No," Shan assured him. "It was no lie. What you have been doing is a miracle, Rinpoche."

The serene smile lit Choje's countenance again.

"You know the world will think that all this was to save one soul," Shan said.

"The soul of a Chinese prosecutor. It is not such a bad lesson, Xiao Shan."

One hundred eighty monks commit suicide to save the soul of their prosecutor, Shan considered. Anywhere else it would be the stuff of legend. But here it was just another day in Tibet.

"But you and I know it is not the real reason."

Choje bowed his hands, the fingers touching at the tips. It was an offering mudra, the flask of treasure. Choje stared at it with a distant smile and pushed his hands toward Shan. Silently Shan did as Choje desired, forming his own hands into the shape. Choje made a gesture of pouring his flask into Shan's, then drew his hands slowly apart, leaving Shan with the flask.

"There," he said. "The treasure is yours."

Shan felt his eyes well up with moisture. "No," he whispered in weak protest, and clenched his eyes, fighting the tears. They will still build the road after you die, he wanted to say. But he knew Choje's answer. It didn't matter, as long as Choje and Nambe gompa had been true.

"The thunder ritual, it is also part of Nambe's duty, isn't it?"

Choje nodded approvingly. "Your eyes have always seen far, my friend. Nambe was already centuries old when the vow was made to protect the gomchen. Nambe was the center of the ritual. It had perfected the practice. For a mortal being to make thunder requires an intense balance, the highest state of meditation. Some say it was the reason we were honored with the protection of Yerpa."

"Trinle and Gendun, they are masters of the ritual."

Choje only smiled.

They remained silent and listened to the mantras beginning outside as the monks finished eating.

"You came with a request," Choje said at last.

"Yes. I must speak to Trinle. About that night. I know he will not talk without your permission."

Choje considered Shan's words. "You are asking a great deal."

"There is still a chance, Rinpoche. A chance to save Nambe and Yerpa. You have to let me find the truth."

"There is always an end to things, Xiao Shan."

"Then if there is to be an end," Shan said, "let it end in light, not in shadow."

"They would give them drugs, you know, if they caught Trinle or Gendun. Like spells, those drugs. They would be powerless to resist the questions. They know that. If the soldiers try to take them, Trinle and Gendun will choose to die. Can you bear that burden?"

"If the soldiers try to take them," Shan replied quickly, "I, too, will choose to die." It was a simple thing, to die when the knobs finally came for you. If you ran away they would shoot. If you ran at them they would shoot. If you resisted they would shoot.

He saw Choje smiling at him and looked down. Shan's hands were still in the mudra, holding the treasure flask, as Choje began to talk.

Twenty minutes later he stood at the edge of the dead zone and took off his prison shirt. He took one step forward. The knobs shouted a warning. Three of them cocked their rifles and aimed directly at him. An officer pulled his pistol and was about to fire into the air when a hand closed around the gun and pushed it down. It was Tan.

"You have less than eighteen hours," Tan growled. "You should be finishing the official report." But as they moved away from the knobs his anger faded. "The Ministry delegation. They are already with Li. They changed the schedule. The trial will be at eight o'clock tomorrow morning."

Shan looked up in alarm. "You have to delay."

"On what grounds?"

"I have a witness."

Chapter Twenty

They arrived before dawn, as Choje had instructed. Do not speak to the purbas, he had said. Do not let the knobs follow. Just be there as the sun rises, at the clearing before the new bridge.

"There was no sign of him?" Shan asked as Sergeant Feng switched off the engine. "Maybe he moved to another barracks. He has no place to go."

"Nope. He's gone. Down the road at nightfall," Feng said. "You won't see him again."

Yeshe's bag had been gone when Shan had returned to the barracks. "He didn't say anything, didn't leave anything?"

Sergeant Feng reached into his pocket. "Only this," he said, laying the ruined rosary on the dashboard, nothing but string and two marker beads. He yawned and lowered the back of his seat. "I know where he went. He asked how to get there. That chemical factory in Lhasa. They hire lots of Tibetans, with or without papers."

Shan put his head in his hands.

"We could ask patrols to pick him up, if you still need him."

"No," Shan replied grimly, and climbed out of the truck.

There was nothing, just the sliver of the moon over the black outline of the mountains. As the stars blinked out he found himself watching for Jao's ghost.

Another vehicle appeared along the road from town, and eased in behind the truck. It was Tan, driving his own car. He was wearing a pistol.

"I don't like it," Tan said. "A witness who hides is useless. How will he testify? He will have to come with us, to the trial. They will ask why he speaks up now, so late." He studied the dark landscape, then looked suspiciously at Shan. "If it is a cultist, they will say he is an accomplice."

Shan continued staring into the heather. "A group of monks were watching the bridge," he explained. "They were trying to cause it to collapse."

Tan muttered a low curse. "By watching it?" he asked bitterly. He looked back at his car, as though he might leave, then followed Shan slowly into the clearing.

"By shouting at it," Shan said. How could he explain the rite of the shards? How could he explain the broken pots above the bridge or at Yerpa, where Trinle and the others trained in the old ritual of thunder? How could he explain the ancient belief that a perfect sound was the most destructive force of nature? "Not a shout, really. Creating sound waves. It was what scared Sergeant Feng that night he fired his pistol. Like a clap of-"

He stopped. In the gathering light he saw a gray shape thirty feet away at the end of the clearing, a large rock that was gradually becoming the shape of a man sitting on the earth. It was Gendun.

They stopped six feet away. "This is a priest of a nearby gompa," Shan explained to Tan, then turned to the old monk. "Can you explain where you were the night of the prosecutor's murder?"

"Above the bridge," Gendun said in a firm, quiet voice, as though he were saying prayers. "In the rocks, chanting."

"Why?"

"In the sixteenth century there was a Mongolian invasion. Priests of my gompa stopped it from reaching Lhadrung by causing an avalanche to fall on the army."

Tan glared furiously at Shan, but before he could turn away Gendun continued. "This bridge. It does not belong here. It is destined to fall away."

He was interrupted by the sound of a heavy truck speeding on the gravel road behind them. As it skidded to a stop Li Aidang jumped out, clad in military fatigues. He took ten steps into the clearing, then snapped out an order. Half a dozen uniformed knobs began leaping from the truck. The major appeared in the headlights, a small automatic gun hanging from his shoulder. The troops formed in a single line along the road, in front of Li.

A strange serenity settled over Gendun, a distant look. He paid no attention to the knobs, but studied the mountains as if trying to remember them for future reference. He could not control his next incarnation. He might rekindle on the floor of a desert hut thousands of miles away.

"The sun had been down maybe an hour when the headlights of a car appeared," he suddenly continued. "It stopped near the bridge and turned out its lights. Then there were voices. Two men, I think, and a woman laughing. I think she was intoxicated."

"A woman?" Shan asked. "There was a woman with Prosecutor Jao?"

"No. This was the first car."

The silence before dawn was like no other. It seemed to hold the troops in a spell. Gendun's words were loud and clear. An owl's call eerily echoed from the gorge.

"Then she screamed. A death scream."

The words snapped Li out of his trance. He stepped into the clearing and moved toward Gendun. Shan stepped in front of him.

"Do not attempt to interfere with the Ministry of Justice," Li snarled. "This man is a conspirator. He admits he was there. He will join Sungpo in the dock."

"We are still conducting an investigation," Shan protested.

"No," Li said fiercely. "It is over. The Ministry will open its trial in three hours. I am scheduled to deliver the prosecution report."

"I don't think so," Tan said, so quietly Shan was not sure if he heard correctly.

Li ignored him and began to gesture for the knobs.

"There will be no trial without the prisoner," Tan continued.

"What are you saying?" Li snapped.

"I had him removed from the guardhouse. At midnight last night."

"Impossible. He had Public Security Guards."

"They were called away. Replaced with some of my aides. Seems there was some confusion about orders."

"You have no authority!" Li barked.

"Until Beijing decides otherwise, I am the senior official in this county." Tan paused and cocked his head toward the hillside.

It was a droning sound that distracted him, as though of frogs, a sound of nature that had not been there before. But then it seemed much closer. In the rising light another priest became visible at the edge of the clearing, ten feet from Gendun. It was Trinle. He was in the lotus position, chanting a mantra in a low nasal tone. Li smirked and approached Trinle, the new object of his furor. Then there was an echoing sound from the opposite side of the clearing. Shan stepped in that direction and discerned another red robe in the brush. Li took another angry step toward Trinle and paused. A third voice joined in, and a fourth, all in the same rhythm, the same tone. The sound seemed to be coming from nowhere, and everywhere.

"Seize them!" Li cried. But the knobs stood, transfixed, staring into the brush.

The day was breaking rapidly now, and Shan could see the robes along the edge of the clearing well enough to count them. Six. Ten. No, more. Fifteen. He recognized several of the faces. Some were purbas. Some were from the mountain, protectors of the gomchen.

Li turned and pulled a truncheon from the belt of a soldier. He walked along the perimeter with a ravenous glare, waving the club. He stopped at the rear of the circle and pounded it against Trinle's back. Trinle did not react. Li shouted in fury for the major, who moved forward with uncertain steps and stopped ten feet from Trinle. Li moved to his side and seemed about to grab his gun.

Shan willed himself to step between them and Trinle. There was new movement at the side of the circle. Sergeant Feng appeared, with the lug wrench from the truck. It was over, Shan realized. That he had lost was no surprise. But that the 404th, and Yerpa, would be lost was unbearable. He ached for it to at least be over quickly. It would be fitting, he absently thought, if the bullet came from Sergeant Feng.

"Back away," he heard Feng growl. But the sergeant was not speaking to him. Feng turned and stood beside Shan, facing Li and the major. The mantra continued.

"You old pig," Li sneered at Feng. "You're finished as a soldier."

"My job is to watch over Comrade Shan," Feng grunted, and braced his feet as though preparing for an attack.

The mantra seemed to swell as it filled the brittle silence again. The major stepped back to his men and ordered them to pull the truncheons from their belts.

Tan materialized at Shan's side. His face was taut. He glanced at Shan with a strangely sad expression, then turned to face Li. "These people," he said, with a gesture that encompassed the circle, "are under my protection."

Li stared at Tan. "Your protection is worthless, Colonel," he snarled. "We are conducting an investigation of you. Corruption in the performance of duties. We revoke your authority."

Tan's hand moved to his holster. The major reached for his machine gun.

Suddenly there was a new sound above the chanting, the hissing of air brakes. They turned, aghast, to see a long shiny bus pulling to a halt. Windows were being pulled down.

"Martha!" someone called in English. "They're doing morning services. Get the damned film changed."

The tourists came out, single file, clicking their cameras, rolling video of the monks, of Shan, of Li and the knobs.

Shan looked into the bus. The man at the wheel was familiar, a face from the marketplace. With him, wearing a trim business suit with a tie, was Miss Taring of the Bureau of Religious Affairs. She began speaking about Buddhist rites, and the closeness of the Buddhists to the forces of nature.

She climbed out and offered to use an American couple's camera to take photos of them with the Chinese soldiers.

The major studied her for a moment, then quickly herded his men into the truck. Li stepped backward. "It doesn't matter," he spat under his breath, "we have already won." He waved to the Americans with an affected smile and climbed in the front of the truck with the major. In moments they were gone. Then, as abruptly as it had arrived, the bus, too, moved on.

Tan sat down in front of Gendun. Instantly the mantra stopped. Trinle appeared and knelt at Gendun's side.

"Tell me about the woman," Tan said.

"She seemed very happy. Then– there is nothing so terrible as the scream of someone unprepared for death. Afterward there were other voices, not hers. That's all."

"Nothing else?"

"Not until the second car. It drove up an hour later. Two doors slammed. There were shouts, a man called out for someone."

"Calling a name?"

"The man from below called 'Are you there?' He said he knew where the flower came from. He said, 'What do you mean I won't need the X-ray machine?' The man above said, 'Esteemed Comrade, I know where you should look.' The man below," Gendun continued, "said he would make a trade, for more evidence."

Shan and the colonel shared a glance. Esteemed Comrade.

"Then he moved up the slope. The voices were much lower, and faded as they climbed. Then there was another sound. Not a shout. A loud groan. Then ten, fifteen minutes later the lights of the car went on. I saw him, maybe a hundred feet from the car. The man in the car got out and ran down the road."

"You said you saw him in the lights."

"Yes."

"You recognized him?" Shan asked.

"Of course. I had seen him before, in the festivals."

"You were not scared?"

"I have nothing to fear of a protecting demon."

They reduced Gendun's testimony to a written statement, which Tan authenticated with his own chop. He did not ask Gendun to remain behind as the monks began to rise and fade into the heather.

"The next morning," Shan asked as Gendun moved to join his companions. "Was there anything unusual?"

"I left before the work crews arrived, as I had been warned. There was only the one thing."

"What thing?"

"The noise. It surprised me, how early they started. Before dawn. The sound of heavy equipment. Not here. Further away. I could only hear it, as though it came from above."

***

They made a solemn procession into the boron mine an hour later, Tan's car in front, the truck of soldiers summoned by Tan's radio, and finally, Shan and Sergeant Feng. They drove straight to the equipment shed, where they selected a heavy tractor with a digging bucket and the mine's bulldozer. The machines were already moving onto the dike by the time the first figures emerged from the buildings.

Rebecca Fowler ran toward them, then stopped and sent Kincaid back for his camera as soon as she recognized Tan. The colonel motioned for her to stop, then deployed soldiers to cut off access to the dike.

"How dare you!" Fowler exploded as soon as she was in earshot. "I'll call Beijing! I'll call the U.S.!"

"Interfere and I'll close the mine," Tan said impassively.

"Damned MFCs!" Kincaid barked, and began snapping photographs of Tan, of the license plates of the vehicles, of the machines and the guards. He paused as he saw Shan. He took another photo, then lowered the camera and stared at Shan uncertainly.

The tractor dug into the dike where it crossed the gorge, where it was the deepest, where Shan remembered seeing equipment in the satellite photos taken just before the dike was completed, where one final gap had remained just before the murder. It was twenty minutes before the bucket struck metal, another twenty minutes before they had confirmed that the car they had found was a Red Flag limousine and hooked it to the bulldozer.

The machine churned against the turf, ripping it apart, until it found traction. The engine heaved and for a moment everything seemed to stop. As the car slowly pulled free of the mud, there was an extraordinary sound, unlike any Shan had ever heard, a ripping, unworldly groan that shook his spine.

The bulldozer did not stop until it had dragged the car nearly to the head of the dike.

Shan looked inside and saw a briefcase.

"Open it," Tan said impatiently.

The door swung open easily, emitting an almost overwhelming smell of decay. Inside the case were Jao's tickets, a thick file, and a satellite photo, cropped down to the poppy fields.

The trunk was jammed. Tan grabbed a crowbar from the bulldozer and popped the lid open. Inside, shrunken within a colorful floral dress, was a young woman. Her mouth was drawn into a hideous grin. Her lifeless eyes seemed to stare right at Shan. Lying on her breast was a dried flower. A red poppy.

A horrifed moan escaped Tan. He turned and hurled the crowbar into the lake. He turned back, his face drained of color. "Comrade Shan," he said, "meet Miss Lihua."

***

Rebecca Fowler stood paralyzed, staring in mute horror into the trunk as Tan moved to the radio in his car. It seemed as though she was drying up as Shan watched, as though any minute she would crumble and blow away in the wind. For a moment he thought she would faint. Then she caught Tan's stare, and the resentment brought her strength back. She began barking orders for the bulldozer to move the car off the dike, for the machines to start filling the gaping hole, for dump trucks to be filled with gravel, then ran toward the hole, shouting for Kincaid.

By the time Shan joined her, she was on her knees. Water was rapidly seeping through the weakened dam. With small, frantic groans she shoved dirt into the hole. The tractor arrived beside her and began pushing dirt with its bucket. A trickle appeared on the side of the hole. As the tractor edged closer the dirt under it began to shift. Fowler screamed, leapt up, and pulled the driver away just as the wall disintegrated and the machine lurched into the hole. The back wall held for the few seconds it took for the hole to fill with water, then it, too, was gone. The tractor was washed into the gorge and the pond broke through.

They watched helplessly as the water hurled down the Dragon Throat, ripping boulders from the sides, collapsing the banks, gathering speed as it dropped under the old suspension bridge toward the plain below in a maelstrom of rock, water, and gravel. Shan became aware of Tan standing beside him. He had binoculars. He was watching his bridge.

But they did not need the lenses to see the wall of water slam into the concrete pillars. The bridge seemed to totter for a moment, like a fragile toy, then it lurched upward and was gone.

Shan remembered the sound of the dike surrendering the car, the shudder of the earth, the wrenching, sucking, squeezing scream of the mud that had shaken his spine.

All it would take, Je had said, was one perfect sound.

***

Kincaid, who had darted past the disinterred limousine to join Fowler, now stood by the open trunk, his jaw open, his eyes disbelieving. "Jesus," he moaned with a cracking voice. "Oh Jesus." He bent as though he needed to touch her, then stopped and slowly straightened. As though guided by some sixth sense he turned to stare at the road leading down to the mine. Following his gaze, Shan saw a new vehicle appear, a bright red Land Rover.

Even from thirty feet away Shan could sense Kincaid's body tighten. "Damn you!" the man screamed, and began running toward the road, bending to grab stones which he hurled in the direction of the still distant vehicle. "Come and see her, you bastards!"

The red truck halted, then began backing up the ridge and disappeared.

Tan had also noticed. He was back on his radio.

Luntok appeared, carrying a blanket to the limousine. The ragyapa were never afraid of the dead. He reverently covered the woman in the trunk then turned and stared at his friend Kincaid. But there was something new in his eyes.

Rebecca Fowler took a step toward the ragyapa engineer. "Whose work crew was responsible for the final fill on this dam?" she asked him in a strained voice. Luntok did not reply but kept staring at Kincaid.

The expression on Kincaid's face hardened momentarily into defiance as he glared back at Luntok. But when he looked at Fowler and Shan, standing together near the car, confusion seemed to overcome him. He bolted toward the office building.